Category: Uncategorized

Carve Every Word: Idaho’s Litigation Privilege to Defamation and Other Civil Claims by Collin R. Flake

by Collin R. Flake

“[S]peak clearly, if you speak at all; Carve every word before you let it fall [. . .].”

– Oliver Wendell Holmes[i]

The recent increase in high-profile defamation lawsuits comes as no surprise against the backdrop of rising polarization in the United States. A few cases illustrate the point.

In 2022, a jury awarded $965 million to families of victims of the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting for defamatory statements made by Alex Jones, who claimed the families were actors in a government plot to impose stricter gun control measures.[ii] Two months later, Oberlin College paid $25 million to the owners of Gibson’s Bakery, who sued for defamation after the college supported protests that damaged their business by branding them as racists for how they handled a shoplifting incident.[iii] In early 2023, Fox News agreed to pay $787.5 million to settle a defamation lawsuit brought by Dominion Voting Systems regarding on-air claims that Dominion’s voting machines were programmed to rig the 2020 presidential election.[iv] A few months later, a jury awarded nearly $3 million to a woman who was defamed by Donald Trump in connection with sexual assault allegations she made against him.[v] And here in Idaho, an Ada County jury recently awarded $52.5 million to St. Luke’s Health System for defamatory statements made by Ammon Bundy and others about the hospital’s treatment of an infant.[vi]

Given the current milieu of divisiveness, the potential exposure to multimillion-dollar judgments, and the ethical obligation to zealously represent clients within the confines of procedural and professional rules, now is an opportune time to brush up on Idaho’s litigation privilege to defamation and other civil claims.

Adopting the Privilege

In true Gem State fashion, the Idaho Supreme Court adopted the litigation privilege over a century ago in a dispute involving a mining company.[vii] Felix Carpenter sued the Grimes Pass Placer Mining Company after it refused to pay him for work and materials furnished at a mill site on Grimes Creek. The company counterclaimed, alleging Carpenter had stolen lumber, piping, and gold nuggets. None too pleased, Carpenter filed a second lawsuit, this time alleging the company’s counterclaim was libelous. The district court dismissed Carpenter’s second action for failure to state a claim, and he appealed.

The Idaho Supreme Court affirmed. After tracing the early development of the litigation privilege to defamation cases in other states and the Ninth Circuit, the Court endorsed the majority view, holding that “the ends of justice and the public good can be best served by allowing litigants to freely plead any pertinent or material matter in a judicial proceeding to which they are parties [. . .].”[viii] Put another way, litigants are only liable for “defamatory matter which is neither pertinent nor material to the subject under inquiry.”[ix] The Court stressed, however, that litigants “cannot be allowed to avail themselves of the protection of the courts to assail and besmirch the reputation of their adversaries,” including by using pleadings to “assassinate character and belie virtue. The privilege must be exercised in good faith.”[x] The Court also held that properly pled allegations that are relevant to a cause of action or defense may be asserted “either with or without malice.”[xi]

Because the mining company’s allegations were pertinent and material to its counterclaim against Carpenter, and there was no indication of bad faith, Carpenter could not sue for libel.

Extending the Privilege Beyond Pleadings

Forty-two years later, the Idaho Supreme Court expanded the litigation privilege in a defamation case involving parties who were attorneys.[xii] Harry Kessler moved to appear as amicus curiae in a case being handled by Charles Richeson, who did not welcome Kessler’s assistance and filed a brief opposing his motion. After the client fired Richeson and hired Kessler as substitute counsel, Kessler wrote a letter to the district judge accusing Richeson of unethical conduct and asking for his opposition brief to be withdrawn. Richeson then sued Kessler for defamation.

Affirming dismissal of the claim, the Court extended the litigation privilege by holding that “it is not absolutely essential that the [defamatory] language be spoken in open court or contained in a pleading, brief or affidavit.”[xiii] Defamatory matter is “absolutely privileged” so long as it is “published in the due course of a judicial proceeding” and has “some reasonable relation to the cause.”[xiv] Moreover, the Court clarified that the term “judicial proceeding is not restricted to trials,” but includes “every proceeding of a judicial nature [. . .].”[xv] It also reinforced its holding in Carpenter that the privilege shields defamatory statements that are malicious and known to be false.[xvi]

The Court concluded that although Kessler’s letter was libelous per se, it was privileged because he submitted it in response to Richeson’s opposition brief. Thus, the defamatory statements were “in the course of, connected with, and related to the judicial proceeding.”[xvii]

Extending the Privilege Beyond Defamation Claims

In 2010, Idaho’s litigation privilege was expanded further to bar other civil claims besides defamation.[xviii] Reed Taylor filed suit against Michael McNichols and his law firm, who were representing a corporation that Taylor held shares in and had sued in a separate action. Taylor alleged McNichols and his firm aided and abetted the corporation in committing tortious acts, misappropriated corporate assets, violated Idaho consumer protection law, and committed professional negligence or breached fiduciary duties. The district court dismissed these claims, and Taylor appealed.

The Idaho Supreme Court comprehensively examined the common-law roots of the litigation privilege, which included nods to Judge Learned Hand and a case from 1585 in the Court of the King’s Bench. The Court then held that “where an attorney is sued by the current or former adversary of his client, as a result of actions or communications that the attorney has taken or made in the course of his representation of his client in the course of litigation, the action is presumed to be barred by the litigation privilege.”[xix] Still, the Court explained that there is an exception to the privilege when an attorney acts outside the scope of his employment or solely for his own interests.[xx] For example, attorneys who engage in malicious prosecution, fraud, or tortious interference out of a “personal desire to harm” are not protected.[xxi]

Because Taylor failed to plead any such facts about McNichols or his firm, the Court affirmed dismissal. And even if Taylor had alleged such misconduct, his claims would have been premature considering the Court’s holding that a lawsuit may only be brought against attorneys after resolution of the underlying case in which the alleged misconduct occurred.[xxii]

"Making a defamatory statement to the press or posting it online – even one that relates to the case and ultimately benefits the client – can violate ethical obligations if it is substantially likely to cause material prejudice, includes a false statement of material fact or law, or lacks evidentiary support."

Applying the Privilege “Broadly”

One of the Idaho Supreme Court’s most recent applications of the litigation privilege came in a defamation case between co-owners of two potato processing businesses.[xxiii] One co-owner, the J.R. Simplot Company, filed suit in a Washington federal court against the other co-owner, Frank Tiegs, who operated Dickinson Frozen Foods. The lawsuit involved dissolution of a business relationship between Simplot and Tiegs, which allegedly was caused by Tiegs’s poor business operations. After filing the suit, Simplot’s attorneys sent a copy of the complaint to a lender of one of the co-owned businesses. Dickinson then sued Simplot and its attorneys for defamation.

The Court put it succinctly: The litigation privilege applies when “(1) ‘the defamatory statement was made in the course of a proceeding’ and (2) it ‘had a reasonable relation to the cause of action of that proceeding [. . .].’”[xxiv] If those two requirements are met, a statement cannot be used as the basis for a defamation claim.

Notably, the Court peppered the word “broadly” throughout its analysis to emphasize the “low bar to invoking litigation privilege,” and the “breadth with which the privilege applies.”[xxv] Citing supreme court decisions from several states, and the Second Restatement of Torts, the Court explained that the test for whether a defamatory statement is reasonably related to the cause of action is not “legal relevancy” from an “evidentiary point of view.”[xxvi] Instead, reasonable relation is “interpreted liberally” to mean “a general frame of reference and relationship to the subject matter of the action.”[xxvii] And “any doubts about the relevance of the [defamatory] statement are resolved in favor of relevancy and pertinency.”[xxviii]

But the broadly applied privilege still has limits. It does not encompass “matters having no materiality or pertinency to the question involved in the suit,” nor does it protect conduct or statements that have “no connection whatever with the litigation.”[xxix]

Simplot’s allegations and the actions of its attorneys did not fit that description. Affirming dismissal, the Court found that litigation privilege barred Dickinson’s defamation claim because Simplot’s allegations about Tiegs’s business practices were reasonably related to the dissolution of the parties’ business relationship.[xxx] Further, since Simplot’s attorneys sent the complaint to a lender of one of the businesses at issue, their conduct was reasonably related to the litigation and within the scope of their employment.[xxxi]

Acknowledging Alternative “Safeguards”

The Idaho Supreme Court’s expansive formulation of the litigation privilege means there is a “risk that a wronged party may be denied civil relief under the law.”[xxxii] Yet the Court has made clear that “a lack of civil redress does not mean immunity from consequence and punishment.”[xxxiii] Procedural and professional rules, as well as the court’s inherent authority, “provide adequate safeguards against abusive and frivolous litigation tactics” that would otherwise form the basis of a defamation claim.[xxxiv]

Under the Idaho Rules of Civil Procedure, attorneys must certify that their pleadings and motions are not being submitted for an improper purpose (such as to harass, cause unnecessary delay, or needlessly increase costs).[xxxv] They are also required to certify that each legal contention is warranted by existing law, and all factual contentions have or will likely have evidentiary support.[xxxvi] Courts “must” sanction attorneys or their firms for violating these rules.[xxxvii]

The Idaho Rules of Professional Conduct also limit what an attorney can say in various ways. For example, Rule 3.3 and Rule 4.1 prohibit knowingly making a false statement of material fact or law to a tribunal or third person.[xxxviii] Rule 3.6 forbids making extrajudicial statements that an attorney knows or reasonably should know will be distributed publicly and are substantially likely to materially prejudice a proceeding.[xxxix] And Rule 4.4 prohibits doing things that have no substantial purpose other than to embarrass, delay, or cause burden.[xl] Failure to comply with these obligations can result in disciplinary proceedings before the Idaho State Bar.[xli]

In addition to these rule-based constraints, attorneys are subject to the “inherent authority” each court must “assess sanctions for bad faith conduct against all parties appearing before it.”[xlii] This includes, among other things, striking pleadings when litigants refuse to comply with court orders based on an invalid assertion of privilege.[xliii]

Carving Every Word

Attorneys are supposed to zealously represent their clients – in fact, they have an ethical obligation to do so.[xliv] But if the objective is to maximize effective advocacy while minimizing the risk of ending up like Alex Jones, Oberlin College, Fox News, Donald Trump, or Ammon Bundy, attorneys should follow the advice of Oliver Wendell Holmes to “speak clearly” and “carve every word.”

While drafting pleadings or briefs (or a letter to a judge, for that matter), attorneys should take care to ensure the contents reasonably relate to the subject matter of the case and promote the client’s interests. Similar caution is warranted when deciding whether to send materials to a non-party or make a public statement, especially if it could be construed as “assail[ing] and besmirch[ing] the reputation of [an] adversary.”[xlv]

Attorneys also should bear in mind that even if statements and conduct are protected under litigation privilege, they may still run afoul of procedural or professional rules. Making a defamatory statement to the press or posting it online – even one that relates to the case and ultimately benefits the client – can violate ethical obligations if it is substantially likely to cause material prejudice, includes a false statement of material fact or law, or lacks evidentiary support. Likewise, actions that may be privileged could still give rise to a bar complaint or sanctions if they have no substantial purpose other than to embarrass or burden the other side.

In light of the contours of Idaho’s litigation privilege and attorneys’ ethical obligations, it seems wise to set expectations with clients early on, especially in emotionally charged litigation. Clients and attorneys alike should remember there are limits to what they can prudently let fall.

Collin R. Flake

Collin R. Flake is an associate general counsel at Melaleuca, Inc. He previously worked as a litigation associate at an international law firm in Cleveland, Ohio. He graduated with his B.S. and M.S. from Brigham Young University and his J.D. from The Ohio State University. His practice focuses on commercial litigation.

[i] Urania: A Rhymed Lesson 22 (William D. Ticknor & Co., 3d ed. 1846).

[ii] Dave Collins, Alex Jones Ordered to Pay $965 Million for Sandy Hook Lies, Associated Press (Oct. 12, 2022, 6:36 PM), https://apnews.com/article/shootings-school-connecticut-conspiracy-alex-jones-3f579380515fdd6eb59f5bf0e3e1c08f.

[iii] Oberlin College Finishes Paying $25M Judgment in Libel Suit, Associated Press (Dec. 16, 2022, 2:31 PM), https://apnews.com/article/business-education-ohio-lawsuits-racism-0408eb2557dcc16749cf2115bcef3a2d.

[iv] Jennifer Peltz & Nicholas Riccardi, How Election Lies, Libel Law Were Key to Fox Defamation Suit, Associated Press (Apr. 18, 2023, 3:43 PM), https://apnews.com/article/fox-news-dominion-lawsuit-trial-explainer-trump-fbd401a951905879d837a8860b3bec5e.

[v] Larry Neumeister, Jennifer Peltz & Michael R. Sisak, Jury Finds Trump Liable for Sexual Abuse, Awards Accuser $5M, Associated Press (May 9, 2023, 6:00 PM), https://apnews.com/article/trump-rape-carroll-trial-fe68259a4b98bb3947d42af9ec83d7db.

[vi] Andrew Selsky, Far-Right Activist Ammon Bundy Loses Idaho Hospital Defamation Case, Must Pay Millions, Associated Press (July 27, 2023, 7:10 AM), https://apnews.com/article/ammon-bundy-idaho-hospital-defamation-verdict-extremism-56af8016c6ae1c47861e9e2861ed99da.

[vii] Carpenter v. Grimes Pass Placer Mining Co., 19 Idaho 384, 114 P. 42 (1911).

[viii] Id. at 387, 114 P. at 45.

[ix] Id.

[x] Id.

[xi] Id. at 388, 114 P. at 46.

[xii] Richeson v. Kessler, 73 Idaho 548, 255 P.2d 707 (1953).

[xiii] Id. at 551, 255 P.2d at 709.

[xiv] Id. at 551–52, 255 P.2d at 709.

[xv] Id. at 551, 255 P.2d at 709 (citation omitted).

[xvi] Id. at 551–52, 255 P.2d at 709.

[xvii] Id. at 551, 255 P.2d at 708–09.

[xviii] Taylor v. McNichols, 149 Idaho 826, 243 P.3d 642 (2010).

[xix] Id. at 836–41, 243 P.3d at 652–57.

[xx] Id. at 841, 243 P.3d at 657; see, e.g., Berkshire Invs., LLC v. Taylor, 153 Idaho 73, 84 n.10, 278 P.3d 943, 954 (2012) (litigation privilege did not apply to defamatory statements made by attorney acting in individual capacity as litigant).

[xxi] Taylor, 149 Idaho at 840–41, 243 P.3d at 656–57.

[xxii] Id. at 843, 243 P.3d at 659.

[xxiii] Dickinson Frozen Foods, Inc. v. J.R. Simplot Co., 164 Idaho 669, 434 P.3d 1275 (2019).

[xxiv] Id. at 678, 434 P.3d at 1284 (quoting Weitz v. Green, 148 Idaho 851, 862, 230 P.3d 743, 754 (2010)).

[xxv] Id. at 678–79, 434 P.3d at 1284–85.

[xxvi] Id. at 679, 434 P.3d at 1285 (citations omitted).

[xxvii] Id. (citations omitted).

[xxviii] Id.

[xxix] Id. at 679–80, 434 P.3d at 1285–86 (citations omitted).

[xxx] Id. at 680–82, 434 P.3d at 1286–88.

[xxxi] Id.

[xxxii] Taylor, 149 Idaho at 841–42, 243 P.3d at 657–58.

[xxxiii] Id. at 842, 243 P.3d at 658.

[xxxiv] Id. (citation omitted).

[xxxv] Idaho R. Civ. P. 11(b)(1).

[xxxvi] Idaho R. Civ. P. 11(b)(2) & (3).

[xxxvii] Idaho R. Civ. P. 11(c)(1).

[xxxviii] Idaho R. Prof. C. 3.3 & 4.1.

[xxxix] Idaho R. Prof. C. 3.6.

[xl] Idaho R. Prof. C. 4.4.

[xli] Idaho R. Prof. C. at Preamble ¶ 19.

[xlii] In re SRBA Case No. 39576, 128 Idaho 246, 256, 912 P.2d 614, 624 (1995).

[xliii] McPherson v. McPherson, 112 Idaho 402, 406–07, 732 P.2d 371, 375–76 (Ct. App. 1987).

[xliv] See Idaho R. Prof. C. at Preamble ¶ 2 (“As advocate, a lawyer zealously asserts the client’s position under the rules of the adversary system.”); see also Idaho R. Prof. C. 3.3 cmt. 2 (“A lawyer acting as an advocate in an adjudicative proceeding has an obligation to present the client’s case with persuasive force.”).

[xlv] Carpenter, 19 Idaho at 387, 114 P. at 45.

Byron Johnson: The Poetry of a Justice by Jamie Armstrong and Sharla Dawn Robinson Ng

by Jamie Armstrong and Sharla Dawn Robinson Ng

Former Idaho Supreme Court Justice Byron Johnson, who died in 2012, left us with a memory of his goodwill as well as insights into his poetic imagination. In the prologue to Poetic Justice, his memoir published by Limberlost Press in 2011, he stated his writing purpose: “[…] I would like to try to tell how my love of poetry and my search for justice sum up my life.”[i] Near the end of his memoir, Justice Johnson wrote, “Twice each month I get together with a group of poets called the Live Poets at the Log Cabin Literary Center [now named “The Cabin”…]. This is a very nurturing opportunity for me to share my poetry with other serious writers.”[ii] To our group of poets, former Justice Johnson was simply “Byron.”

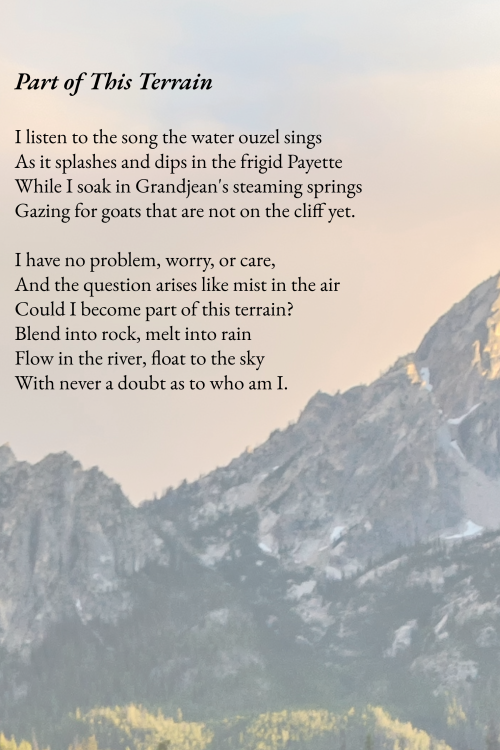

To honor Byron’s presence in the Live Poets Society (“LPS”), the group included the latter quotation as well as one of Byron’s poems in their recently published anthology. His poem “Part of this Terrain” appears in A Quiet Wind Speaks (2022), an anthology of poems, which celebrates 25-plus years of the Live Poets Society in Boise. In responding to the book, the Editorial Advisory Board of The Advocate stated that an article which discusses Byron’s contribution to the anthology would be of interest to them to consider for publication.

Two of the book’s editors, Sharla and Jamie, are now pleased to share with you our understanding of Byron’s contribution to the poetry anthology. His contribution goes beyond the literal inclusion of one poem and two brief comments from his memoir. In our view, Byon’s contribution to the anthology began with his search for appropriate feedback on his newly written poems. This quest led him to the LPS and a special relationship with the other poets in the group. By presenting the process by which Byron developed himself as a poet in retirement, along with some of his poems, we are sharing with you the foundation of our wish to honor Byron in our celebratory anthology of poems.

Byron’s Initial Poetry Workshops

“In 1997, I concluded that poetry would be my new life.”[iii] And indeed, it was. After Justice Johnson retired from the Idaho Supreme Court in 1999, he made writing poetry a priority. Near and far, Byron actively sought to develop his skills in poetry writing workshops. To prepare for his retired life as a poet, he had written poems, attended local workshops, hosted a workshop in Idaho City, and successfully submitted a poem to a local poetry competition.

After his retirement, Byron explored poetry writing outside Idaho. He was accepted to the Frost Festival, an all-poetry workshop in Franconia, New Hampshire, in 1999, and he returned in 2000. Two years later, he attended the more advanced and selective Frost Seminar. There, he felt humbled to discover many writers who had “been writing poetry seriously for a long time.”[iv] The mindset for writing poetry is different from that of legal writing. If he felt challenged by this elite environment, that would be understandable.

By the time Byron joined the Live Poets Society in 2007, he knew that to grow as a poet he needed “nurturing,” and he was remarkably confident in himself as a human being to say so in his memoir. Since Byron’s passing, Laura Johnson, his daughter, manages his journals and poetry, which he left in her care. Reflecting on her father’s membership in the LPS, she commented on his use of the word “nurturing” to describe his experience with the group. “Nurturing is no small claim for a man such as my father.”[v]

In the epilogue of Poetic Justice, Byron reminds his readers, “I have done my best in these pages to give an accurate portrayal of how poetry and justice have intertwined in my life.” Byron’s memoir contains some of the poems he wrote and workshopped with the LPS. The other Live Poets and Byron served one another well by talking about the content that each poem uniquely expresses and developing the craft of their own poetry.

Give-and-Take Talk with Other Serious Writers

One may wonder just how a poets’ group proceeds with the task of writing poems together. A simple give-and-take model of communication evolved early in the Live Poets’ 25-year history to accommodate the Poets’ wide variety of interests and poem topics (such as moments in nature, interpersonal relationships, and perspectives on society or social issues).

In this communication model, safety and reciprocity are essential features. The give-and-take model involves deep listening. The feedback comes respectfully, each responder knowing that the poet considers their poems to be important and is striving to refine them so that they will be received well by anyone who later hears or reads them. In workshop meetings, there is plenty of praise coupled with occasional gentle suggestions for improvement. This nurturing interaction builds a poet’s confidence and tolerance for feedback. This give-and-take also tends to elicit creative responses from its members.

"I have done my best in these pages to give an accurate portrayal of how poetry and justice have intertwined in my life.”

Fresh ideas readily spring from what is available, like the way legal conclusions are reached when precedent is applied to new fact patterns, or the way new proposals can come to a negotiation table. Furthermore, Live Poets see one another as peers on equal footing. Whether workshopping an individual’s separate poems or working on a group project such as A Quiet Wind Speaks, poets take turns evaluating ideas based on their merits without regard to where they originated or who brought them forward.

For the then-members of the LPS, it was an honor to share their writing lives with Byron, a man whose responses to their poems were informed by deep awareness of the political and social events of the day. His mere presence reinforced the group’s belief that poetry can matter. And Byron consistently behaved as if poetry does matter. Twice a month, he came to each meeting with a poem to share. His responses to others’ poems were encouraging, honest, and helpful.

For example, handwritten onto copies of several of Sharla’s poems from 2011 are his responses which contain these qualities. Three of Byron’s handwritten comments read as follows: “A lesson in letting every day happenings be a source of our poetic inspiration;” “Seems a little stilted in view of other images noted above;” “This causes me to ponder whether it really fits…. I would enjoy seeing a new draft.”[vii] Byron’s gentle and inquiring manner encouraged a mindset of mutual respect that comes with the back-and-forth nature of a give-and-take conversation.

Byron became a dear member of our little community of poets. In the twice-monthly workshop sessions, Byron epitomized what it means to participate in the group’s feedback sessions. He consistently made comments that showed his deep understanding of a poem’s meaning as well as his respect for the poet who had shared the poem. The presenting poet appreciated this kind of feedback from Byron because it meant that both the poet and their poem were taken seriously. By building trust through consistently safe and reciprocal interactions with the other Live Poets, Byron reinforced the group’s give-and-take model of communication. For these reasons and more, the group naturally chose to honor Byron’s memory and poetry in their recent anthology.

Byron’s Poetry

During the five years Byron was a member of the Live Poets Society, he brought poems on a variety of subjects to the workshop meetings: poems about his being in nature,[ix] or about a childhood memory of riding in a neighbor’s sidecar,[x] his Grampa Royal Gold,[xi] or poems from his undergraduate days at Harvard College,[xii] a poem about the cemetery in historic Idaho City,[xiii] or his world travels.[xiv] During his years with the Live Poets, he brought dozens of these poems to workshop at our twice-monthly meetings, including half of the poems that he eventually weaved through the chapters of Poetic Justice.

In this portion of the article, we’ve selected several of the poems in which Byron reveals his essential connection to Idaho’s natural world, where he felt most comfortable with himself, and his spirit felt at home.

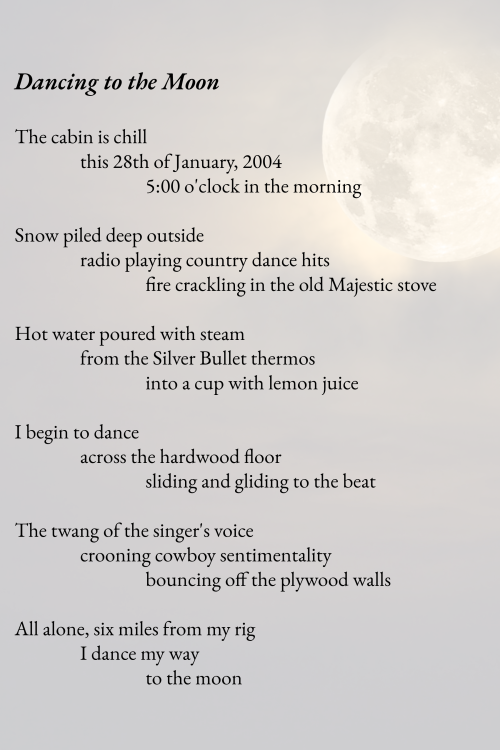

“Dancing to the Moon”

Along with pursuing the craft of his poetry once he retired, Byron also plunged into Idaho’s wilderness. The day after he retired from the Supreme Court, he “skied into Grandjean on the South Fork of the Payette River to spend a month, resting, reading, writing poetry, skiing, soaking in the hot springs, and watching mountain goats and eagles.”[xv] He would return there for his month-long “retreat” each winter through 2006.

Although he thrived on such personal isolation in the wilderness for an extended period each year, Byron the Live Poet was a very relatable person. One near-founding member of the Live Poets Society, Vera Noyce, described Byron’s poetry as indicative of “[…] a gregarious yet solitary individual.”[xvi] One example of this is Byron’s poem, “Dancing to the Moon,”[xvii] which gives readers a peek into this 21st-century mountain man’s cabin and the experience of a joyful moment of dancing alone.

This poem (previously unpublished) tells the story of an unlikely activity for most anyone, let alone a retired justice and lawyer who had presented his serious side to the public while he attended to the serious business of the law. At the unlikely hour of 5 AM, alone and miles from civilization, Byron dances to country music. Then, true to a pattern with which his fellow Poets had become familiar, Byron’s poem ends with a burst of imagination: he decides to “dance [his] way to the moon.” Vera Noyce had this to say about the poem: “I admired and envied Byron’s silent winter retreats in Grandjean where he set his creative juices afire and wrote such lovely poetry. A favorite of mine is his poem ‘Dancing to the Moon’ written in January 2004.”[xviii] Perhaps this poem works so well because it vividly evokes a basic cabin scene and exuberance in a moment of spontaneous dancing.

“My Place in the Universe”

In the first line of his poem, “My Place in the Universe,”[xix] Byron states, “I’m just a mountain man at heart.” Within this line, he found the title for Chapter Eight in Poetic Justice: “Mountain Man.” In the first five stanzas of this poem, Byron asserts his heart’s love of mountain settings. He states what he loves about camping there, which includes bringing in water, building a fire, and pitching a tent. These activities he calls the “necessities of life.” Sitting by his campfire, he can think in peace, listen to the morning songs of birds, or watch the acrobatics of squirrels – all of which keep him from having to think about “worldly affairs.”

The poem ends with this four-line stanza (forward slashes indicating line breaks): “Where else but the mountains/ can you feel so close to the presence/ of whatever it is, in which we live,/ and move and have our being.” In this kind of special moment, when human beings “have our being,” we may experience fulfillment in the profound knowledge that we belong right where we are in the universe and are at peace with ourselves. This concluding stanza begins with the words “Where else,” a phrase that usually starts a question. Yet in this instance, Byron does not end his poem with a question mark; rather, he completes the poem with a declaration that he thrives in the mountains where he knows he is a part of everything.

“My Soul Is Flowing in this River”

When Byron wrote “My Place in the Universe,” he was speaking from the perspective of a lifelong connection to the mountains that had begun in the summers of his youth. Camping with his grandparents on the South Fork of the Payette River, he began to build an intimate relationship with the natural world in the wilds of Idaho’s mountains. Decades later, Byron revealed what these times meant to him: “The South Fork is where I feel most at home and at peace with myself.”[xx] With these words of introduction early in his memoir, Byron presented his poem, “My Soul Is Flowing in this River.”[xxi] Referring to “My Soul” in the title, the poem’s first lines say, “it echoes in the river’s roar/ rolling over rocks worn smooth/ by time’s eternal rush.”

Near the poem’s beginning, Byron expresses a reverential and sacred relationship to the river when he says, “you baptized me” even as he addresses the river as “mother-father.” This river will ultimately hold his soul, which he calls “the essence of my being.” His soul being held in the river’s “everlasting flow” after his death echoes the river’s action of cuddling Byron when he was a youth.

His being held in the river’s flow, a kind of liquid urn for his ashes, also echoes the sense of the all-embracing presence “of whatever it is” that Byron felt in the mountains, which he expressed in “My Place in the Universe” (discussed earlier). Through sharing poems about this intimate aspect of his life in the wild, Byron revealed his trust in people close to him as well as of the general reading public.

“Idaho Needs Poets More than Judges”

Laura Johnson spoke about one poem in particular, “Idaho Needs Poets More than Judges,”[xxii] which showed her father’s “… intent in shifting his life’s focus from the Law to being poetic; and his profound love and respect for Idaho–its natural spaces, its wildlife, its people. “[xxiii]

The last portion of Byron’s poem conveys his reasons for turning “to poetry after the Court:” “Idaho calls poets softly/ to see/ her early morning meadows/ with dew drops on the camas/ to hear/ her rampant rivers/ tumbling over rugged rocks/ to smell/ her pungent pines/ drifting on evening breezes.” He concludes the poem with this stanza: “Idaho needs poets more than judges/ to protect her innocence/ from plunder.” In these lines, Byron personified the wilderness. He speaks as a poet, and his strong “mountain-man” inclination to protect nature is expressed openly. This stance reinforces our understanding of part of his motivation to write poetry after the law.

From sitting by his campfire where he watched life around him to imagining his soul flowing in the Payette, through his poetry Byron revealed his keen abilities of observation. He also expressed his deep, abiding connection to the wilderness regions of Idaho and his certainty of its ongoing importance to all her citizens. Taken together, the previous four poems show the complex, lifelong connection that Byron developed with Idaho’s wild places.

“Part of This Terrain” in A Quiet Wind Speaks

Byron often liked to soak in the hot springs after a day of skiing and other activities each winter when he spent a month in the wilderness. He enjoyed the enervating warmth of the water that relaxes most of the body while one’s head is stimulated by the chill of the surrounding winter air. During such a generative moment, “Part of This Terrain”[xxiv] came to Byron. His eyes scanned the terrain and sky for signs of wildlife as he listened to the sounds of water and the wind. While the smooth rock of the hot springs cradled his being, his mind was set free to wander, reflect, and imagine.

In this poem, while taking care of himself in the wilderness, Byron reveals his core connection with Idaho’s wild places where he could observe the mountains, rivers, and wildlife. While completely absorbed in nature, he clearly states that he knows who he is, his identity as a human being.

As in many anthologies, the poems in A Quiet Wind Speaks were not constrained by or prescribed to a particular theme. Rather, each poem stands unique among the other unique poems, like a forest scene populated with various natural elements who belong together in the environment. In “Part of this Terrain,” a well-crafted poem, Byron expresses something essential about himself in nature, so the Live Poets selected it for inclusion in A Quiet Wind Speaks.

Byron’s Wake

On January 6, 2013, the family and friends of Byron gathered at the recently completed events center in Barber Park on the Boise River for “A Wake Celebrating the Life of Byron Johnson, 1937-2012.” The printed memento for the occasion included two of Byron’s poems, one of them being “Part of this Terrain.” Those assembled were touched by feelings of loss in Byron’s absence. At the same time, we were buoyed by feelings of appreciation of Byron’s life and our joy to be in it with him for as long as we had known him. It felt good to be gathered with people who felt close to him.

Byron loved a good party, as evidenced by the abundance of food, drink, music, readings, and good cheer at his wake. After all, this one was the real thing. Three “practice wakes” (wake-style gatherings in honor of Byron’s life as if he were dead) had occurred for Byron at various times during previous years.

row: Dee Gore, Jamie Armstrong, Tish Thornton.

That Byron loved a lively party was also evident in the way Byron had joined in at the annual Christmas party, which the Live Poets celebrated at The Cabin on the first Wednesday in December for many consecutive years. In a personal comment,[xxv] Vera Noyce recalled the ways that Byron livened up those parties with his refreshments and good cheer: “Byron entered enthusiastically into the festivities, introducing the group to and providing us with outstanding hot buttered rums. His toast at the 2010 party celebrated friendship. It reads, in part:

…to toast poetry and poets

who fill our lives up

The warmth of friendship

comforts us between sips

of this delicious elixir

through poetic lips.

It also was Byron’s kind presence and warm friendship that the Live Poets honored by including one of his poems in our book. In this way the Live Poets continue to toast the memory of Byron Johnson.

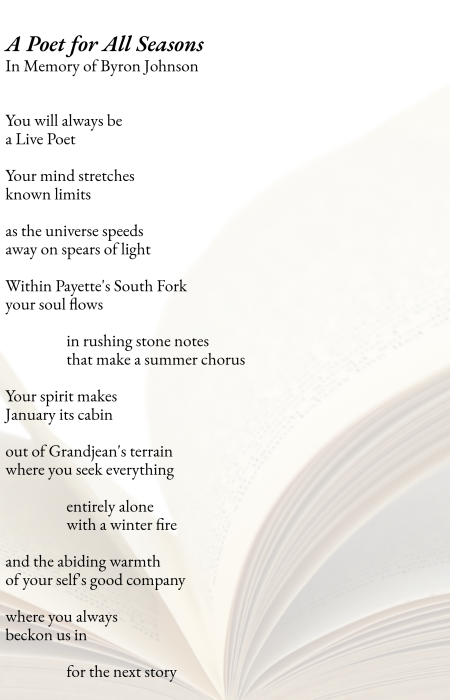

At Byron’s wake, Jamie presented a poem that he had written in memory of Byron, to celebrate his life. In “A Poet for All Seasons,” there are references to Bryon’s poems, “My Soul Is Flowing in this River” and “Part of this Terrain,” which were discussed earlier in this article.

From attorney to Idaho Supreme Court Justice to poet, Byron Johnson had a presence among the Live Poets, which was as natural and evolving as the Idaho wilderness he loved. He remained remarkably open to empathy for the people he encountered along the way. This capacity came through in his poems and enriched the poetry workshop experience for the members of the Live Poets Society. More than 11 years after his death, the group continues to recall Byron’s way of being in the group, his goodwill, and the uniquely personal way his imagination invited the reading public into his trust. As a tribute to Byron Johnson, in gratitude for his being with us, we made an honored place for him in the Live Poets’ 25th anniversary anthology of poems.

NOTE: Copies of Byron Johnson’s memoir, Poetic Justice, may be purchased through the book’s publisher, Limberlost Press at www.limberlostpress.com. Attorneys with Idaho State Bar numbers may check out a copy of the book from the Idaho State Law Library.

Jamie Armstrong

Jamie Armstrong co-founded the Live Poets Society in Boise. His poems appeared in The Cabin’s Writers in the Attic. As an education professor at Boise State, he received an Idaho Humanities Council grant for Culture of the Irrigated West, a video featuring seven of his poems. Retired, Jamie lives in coastal northern California.

Sharla Dawn Robinson Ng

Between periods of employment at the Idaho Industrial Commission, Sharla Dawn Robinson Ng wrote poetry for creative expression, joining the Live Poets Society in 2010. In recent years she has led their meetings and readings. As editor of AQWS, she’s learned that the group’s give-and-take model of communication encourages generative and kindhearted discussion.

[i]. Byron Johnson, Poetic Justice: A Memoir, 1 (1st Edition, 2011).

[ii]. Id. at 237.

[iii]. Id. at 228.

[iv]. Id. at 230.

[v]. Email from Laura Johnson to author Jamie Armstrong, May 21, 2023 (on file with author).

[vi]. Byron Johnson, Poetic Justice: A Memoir, 239 (1st Edition, 2011).

[vii]. Comment by Byron Johnson, Live Poet, to author and Live Poet Sharla Robinson Ng, July, 2010; March, April, May, 2011(on file with author).

[viii]. Email from Vera Noyce, Live Poet, to author Sharla Robinson Ng, May 9, 2023 (on file with author).

[ix]. Byron Johnson, “My Soul Is Flowing in This River” in Poetic Justice: A Memoir,17 (1st Edition, 2011); Id., “Part of this Terrain,” at 215.

[x]. Id., “The Sidecar,” at 10.

[xi]. Id., untitled poem at 51-52.

[xii]. Id., untitled poem at 31, On His Sight, at 34, untitled poem at 37.

[xiii]. Id, “Gold Rush Cemetery,” at 164.

[xiv]. Id., “Denali Pass – 18,300 Feet,” at 219-220; “The Grande Traverse,” at 221-222; “Images Of China – 2002,” at 223-224; “Namaste, Infinite India,” at 235-236.

[xv]. Byron Johnson, Poetic Justice: A Memoir, 229 (1st Edition, 2011).

[xvi]. Email from Vera Noyce, Live Poet, to author Sharla Robinson Ng, May 9, 2023 (on file with author).

[xvii]. Byron Johnson, Dancing to the Moon (unpublished poem) (on file with author).

[xviii]. Email from Vera Noyce, Live Poet, to author Sharla Robinson Ng, May 9, 2023 (on file with author).

[xix]. Byron Johnson, Poetic Justice: A Memoir, 213-214 (1st Edition, 2011).

[xx]. Id. at 17-18.

[xxi]. Id.

[xxii]. Byron Johnson, Poetic Justice: A Memoir, 227-228 (1st Edition, 2011).

[xxiii]. Email from Laura Johnson to author Jamie Armstrong, May 21, 2023 (on file with author).

[xxiv]. Byron Johnson, Poetic Justice: A Memoir, 215 (1st Edition, 2011).

[xxv]. Email from Vera Noyce, Live Poet, to author Sharla Robinson Ng, May 9, 2023 (on file with author).

Shortcomings of the Recklessness Instruction by Nicole L. Cannon and Casey J. Hemmer

by Nicole L. Cannon and Casey J. Hemmer

Recklessness is not recognized as a separate tort in Idaho but is merely a degree of negligence.[i] As a result, Idaho does not allow a party to argue for increased damages merely based on a finding of recklessness. However, a finding of recklessness can still have a significant impact on damages awarded in civil cases. Under Idaho’s non-economic damages cap, no party may obtain non-economic damages above the cap as specified in the Idaho statute.[ii] An exception to this rule exists where the fact finder determines that the tortfeasor acted willfully, recklessly, or feloniously. In those instances, the non-economic damages cap does not apply.[iii] The question then becomes, when do these exceptions apply?

This article addresses the contexts in which the exceptions to the non-economic damages cap apply, focusing on the application of “recklessness.” To understand the difficulties of determining what constitutes recklessness, a review of relevant caselaw is presented in the following. An analysis of recent legislation regarding recklessness is also provided. Finally, the article addresses the significant difficulties with the legislative enactments regarding recklessness.

Willfully, Recklessly, and Feloniously

As mentioned, the three exceptions to the non-economic damages cap ask the fact finder to determine whether the tortfeasor acted willfully, recklessly, or feloniously. Regarding the latter, there does not appear to be any Idaho caselaw addressing how to apply this exception. However, the language of the statute is relatively straightforward, in that the non-economic damages cap will not apply to “[c]auses of action arising out of an act or acts which the trier of fact finds beyond a reasonable doubt would constitute a felony under state or federal law.”[iv] This language requires the plaintiff to effectively prove that the tortfeasor committed a felony, utilizing a “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard, and that the claim arises out of the felonious conduct.

Reckless Caselaw

There have been numerous published cases from the Idaho Supreme Court defining recklessness for purposes of jury instructions. Not all these instructions have been identical. For instance, in Carrillo v. Boise Tire Co.,[v] the following instruction was given: “The words ‘willful or reckless’ when used in these instructions and when applied to the allegations in this case, mean more than ordinary negligence. The words mean intentional or reckless actions, taken under circumstances where the actor knew or should have known that the actions not only created an unreasonable risk of harm to another, but involved a high degree of probability that such harm would actually result.”

A few years later, the Court approved the following instruction with a slight variation from the Carrillo instruction: “The words ‘willful or reckless misconduct’ when used in these instructions and when applied to the allegations in this case, mean more than ordinary negligence. The words mean intentional or reckless actions, taken under circumstances where the actor knew or should have known that the actions not only created an unreasonable risk of harm to another, but involved a high degree of probability that such harm would actually result.”[vi]

Another slight variation was approved in Ballard v. Kerr: “Willful or reckless misconduct, when used in these instructions and when applied to the allegations in this case, means more than ordinary negligence. Willful or reckless misconduct means intentional or reckless actions, taken under circumstances where the actor knew or should have known not only that his actions created an unreasonable risk of harm to another, but also that his actions involved a high degree of probability that such harm would actually result.”[vii]

Then, in Herrett v. St. Luke’s Magic Valley Reg’l Med. Ctr., the following instruction was approved: “Conduct is reckless when a person makes a conscious choice as to his or her course of action under circumstances where the person knew or should have known that such action created a high probability that harm would actually result. The term ‘reckless’ does not require an intent to cause harm. Reckless means more than ordinary negligence.”[viii]

Most recently, the Supreme Court approved of the use of Idaho Civil Jury Instruction (“IDJI”) 2.25 for the definition of “willful and wanton” without comment on the multiple versions of other instructions that have been used in the past.[ix]

While the general rule is that IDJIs are to be used where they are appropriate, that same rule states that courts may vary from the IDJIs when “it finds that a different instruction more adequately, accurately or clearly states the law.”[x] As shown, the Supreme Court is fairly permissive when it comes to alternate jury instructions, so long as the instruction given accurately sets forth the law.

"The recently codified definition leaves a number of important questions unanswered, providing juries with little guidance on how to decide this important question."

Statutory Recklessness

As a result of the multiplicity of potential recklessness instructions, the Idaho Legislature appears to have stepped in to attempt resolve this issue. In 2020, the Legislature enacted (and the governor signed) a bill that provided specific language as to what amounts to recklessness for purposes of addressing the non-economic damages cap.[xi]

The newly added language, codified as Idaho Code § 6-1601(10) reads: “‘Willful or reckless misconduct’ means conduct in which a person makes a conscious choice as to the person’s course of conduct under circumstances in which the person knows or should know that such conduct both creates an unreasonable risk of harm to another and involves a high probability that such harm will actually result.”

In enacting this language, the Legislature did not provide any guidance as to how or whether this language is to be used by a jury, though it had provided such guidance in the past.[xii] However, a reasonable presumption is that when the Idaho Legislature created a statutory definition of recklessness for purposes of the non-economic damages cap, this is likely to be the applicable language for instructing the jury when they are asked to determine whether conduct was reckless.

Problems with the Recklessness Definition

Unfortunately, despite the Legislature’s efforts, this revamping of I.C. § 6-1601(10) did little, if anything, to help allay confusion and provide a basis for a clearer jury instruction. On the contrary, the recently codified definition leaves a number of important questions unanswered, providing juries with little guidance on how to decide this important question.

To begin with, the language from the 2020 legislative revision does not provide sufficient guidance for a jury to determine what conduct constitutes foreseeability, or the “high probability that such harm will actually result.” For example, in the context of a medical malpractice case, in order “[t]o establish proximate cause, a plaintiff must demonstrate that the provider’s negligence was both the actual and legal (proximate) cause of his or her injury.”[xiii] Actual cause is a “factual question focusing on the antecedent factors producing a particular consequence.”[xiv] Legal cause exists when “it is reasonably foreseeable that such harm would flow from the negligent conduct.”[xv] However, there is no duty to guard against risks which a defendant cannot reasonably foresee. As such, if there is no foreseeability for an outcome, there can be no liability.[xvi]

Given this, what does foreseeability entail? In other words, how “high” must the probability be that the harm may occur for a jury to determine the defendant’s actions constitute recklessness? Importantly, one must not forget the Legislature intentionally used the word “actually” in characterizing the foreseeability that the harm may occur. In analyzing statutory language, courts must give effect to every word of the statute and every word of the statute needs to be given its plain meaning. Critically for these purposes, the Legislature did not simply require a “high probability of harm” to find recklessness, but rather a “high probability that such harm will actually result.” The second part of this clause, “will actually result,” functions to qualify the words “high probability” which immediately precede it.

Merriam Webster defines “actually” as: (1) “in act or in fact: really,” and (2) “in point of fact.”[xvii] Other courts in various contexts have held the word “actually” has independent meaning within a statute and provides clarity or qualification to other, adjacent statutory terms.[xviii]

Thus, to give the proper and intended effect to the term “actually” in I.C. § 6-1601(10), “high probability” must be read to require harm that is “in fact” going to occur, harm which is “really” going to occur. Thus, the term “actually” intensifies and limits “high probability” to situations where the harm is all but inevitable, or all but certain to occur. A reading of the statute which merely focuses on “high probability” and ignores the term “actually” impermissibly renders the word a nullity and dilutes the intended meaning of “high probability.”

It appears the Idaho Court of Appeals was mindful of this increased burden of proof. In Galloway v. Walker,[xix] the trial court charged the jury using the definition of reckless found in the Restatement (Second) of Torts § 500 (1965), which stated:

A person’s conduct is reckless if he does an act or intentionally fails to do an act which it is his duty to the other to do, knowing or having reason to know of facts which would lead a reasonable man to realize, not only that his conduct creates an unreasonable risk of physical harm to another, but also that such risk is substantially greater than that which is necessary, under the circumstances.

The “high probability” language did not appear in the charge because the Idaho Supreme Court had only recently updated IDJI2d 2.25 to include this language. According to the Court of Appeals, the updated charge which provided the conduct “involved a high degree of probability the harm would actually result” sets a higher standard of proof for plaintiff than the language of the Restatement. Thus, Galloway recognized the high burden this element places on a plaintiff.

However, without further guidance from either the courts or the Legislature, this important question is open for interpretation. If a jury is struggling with this determination, how high the probability must be before a course of action is considered to be reckless, with no assistance, different juries could reach wildly differing results on the same set of facts before them.

Additionally, hand in hand with the proceeding question, there is no guidance as to what the term “such harm” means in this context, and what plaintiffs must prove in order to meet this burden. In the context of medical malpractice, does the term “such harm” mean that a patient may suffer some type of undefined poor outcome? Or does it mean the specific harm which actually occurred?[xx]

Finally, it is certainly notable the Legislature chose to explicitly include the unreasonable risk language which had been omitted in Herrett, signifying the “unreasonable risk” was a separate and distinct element from “high probability that such harm will actually result.” Any other reading of the statute would fail to give effect to “unreasonable risk” and render it superfluous. This too, however, is open to interpretation, with little guidance. “Unreasonable” to whom? To the person facing the risk, or to the person engaging in the course of conduct? What might constitute “unreasonable” to a highly trained professional, working within their field, may well look starkly different to a lay person without similar training.

Given the uncertainty surrounding the current definition of “willful or reckless misconduct” as provided by I.C. § 6-1601(10), the courts and attorneys (and juries) in Idaho are left in a position where the determination of whether any specific conduct was “reckless” is nearly impossible to decide with any sort of consistency. Where the statutory definition could reasonably be interpreted multiple ways, it is challenging for anyone involved in the litigation process to reasonably evaluate their case. Moreover, the lack of clarity provides a real risk of vastly disparate outcomes in similarly situated cases. As such, it is imperative that more clear guidance be given regarding what truly does constitute “reckless misconduct” in Idaho.

We urge members of the Bar to discuss this important issue with relevant industry groups to ensure those most impacted by it fully understand the implications of this uncertainty. Getting a resolution to these unanswered questions may require a concerted effort, either in the courts or the Legislature, or both, but given the importance of having an answer, we believe it is a worthwhile effort.

Nicole L. Cannon

Nicole L. Cannon graduated from the University of Utah College of Law in 1996. Nikki Cannon began her law practice as a deputy prosecuting attorney in Minidoka County for approximately 12 years. After, Nikki joined the firm of Tolman & Brizee, P.C. in Twin Falls, and shifted the focus of her practice to insurance defense. Nikki is now a proud partner in Tolman Brizee & Cannon, continuing her work in defending clients in various civil matters. When she’s not working, Nikki enjoys traveling, cooking, and spending time in Idaho’s great outdoors with her husband and their golden retriever.

Casey J. Hemmer

Casey J. Hemmer graduated from the William and Mary School of Law and has been practicing law since 2005. For 12 years he practiced criminal law, first as a deputy prosecuting attorney and then as a deputy attorney general for the State of Idaho. Mr. Hemmer joined Tolman Brizee & Cannon in September 2019. He currently handles cases involving medical malpractice, product liability, commercial liability, and general liability (casualty and personal injury). Mr. Hemmer shares his life outside the law with his wife and their two children.

[i] Noel v. City of Rigby, 166 Idaho 575, 590, 462 P.3d 103, 118 (2020).

[ii] Idaho Code § 6-1603(1).

[iii] I.C. § 6-1603(4).

[iv] I.C. § 6-1603(4)(b).

[v] Carrillo v. Boise Tire Co., 152 Idaho 741, 747, 274 P.3d 1256, 1262 (2012).

[vi] Hennefer v. Blaine Cty. Sch. Dist., 158 Idaho 242, 253, 346 P.3d 259, 270 (2015).

[vii] Ballard v. Kerr, 160 Idaho 674, 708, 378 P.3d 464, 498 (2016).

[viii] Herrett v. St. Luke’s Magic Valley Reg’l Med. Ctr., Ltd., 164 Idaho 129, 136, 426 P.3d 480, 487 (2018).

[ix] Noel at 579, 462 P.3d at 111.

[x] Idaho Rule of Civil Procedure 51(g).

[xi] H.B. 582, 65th Leg., 2d Sess. (Idaho 2020).

[xii] See I.C. § 6-1603(3), which sets forth the jury procedure for application of the non-economic damages cap.

[xiii] Coombs v. Curnow, 148 Idaho 129, 139, 219 P.3d 453, 463 (2009).

[xiv] Id. at 139-40, 219 P.3d at 436-64.

[xv] Id. at 140, 219 P.3d at 464 (citation and internal quotation marks omitted).

[xvi] 57 Am.Jur.2d Negligence § 125.

[xvii] “Actually,” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/actually (las accessed March 28, 2023).

[xviii] See Bradbury v. Idaho Judicial Council, 149 Idaho 107, 116-17, 233 P.3d 38, 47-48 (2009) (employing the Webster’s Dictionary definition of “actually” to determine the “common sense interpretation of ‘actually reside’”); see also Strickland v. Waymire, 126 Nev. 230, 236, 235 P.3d 605, 609-10 (Nev. 2010) (setting forth Webster’s definition of “actually” as “an actual or existing fact; really,” and holding the word “actually” worked to “vivify” an adjacent term in the constitutional clause at issue. “This ‘may not be very heavy work for the [word ‘actually’] to perform, but a job is a job, and enough to bar the rule against redundancy from disqualifying an otherwise sensible reading.” Gutierrez v. Ada, 528 U.S. 250, 258, 120 S. Ct. 740, 145 L.Ed.2d 747 (2000)”).

[xix] Galloway v. Walker, 140 Idaho 672, 676, 99 P.3d 625, 629 (Ct. App. 2004).

[xx] It is worth noting that the Idaho Supreme Court, evaluating “reckless, willful and wanton” in the context of the Idaho Tort Claims Act, recently stated that the “specific kind of harm must be foreseeable.” Mattson v. Idaho Dep’t of Health & Welfare, 172 Idaho 66, 529 P.3d 731, 742 (2023) (emphasis in original). The definition of “reckless, willful and wanton conduct” under the ITCA is nearly identical to the definition provided by I.C. 6-1601(10). Compare I.C. 6-904C.

The Uses and Limits of a Motion for Reconsideration in Idaho by Stephen L. Adams and W. Christopher Pooser

by Stephen L. Adams and W. Christopher Pooser

A motion for reconsideration is a standard motion in civil practice, and most times such motions are addressed pro forma. However, such motions can be misused, and the Idaho Supreme Court has indicated misuse can result in sanctions against the attorney. These motions deserve more thought than they are often given.

A motion for reconsideration is not simply a vehicle to challenge a ruling that a party does not like. There are minimum requirements imposed on a party seeking reconsideration. This article addresses the scope of motions for reconsideration in Idaho, as well as the limits on such motions.

Authority For and the Purpose of Motions for Reconsideration

Let’s begin by comparing the motions with their federal counterpart. Under Idaho Rule of Civil Procedure 11.2(b)(1), “A motion to reconsider any order of the trial court entered before final judgment may be made at any time prior to or within 14 days after the entry of a final judgment.”[i] This rule does not say anything about the scope of a motion for reconsideration, only the timing. However, it presupposes that motions for reconsideration are allowed under Idaho law. In fact, trial courts have no discretion on whether to entertain a motion for reconsideration. They must.[ii]

In those ways, motions for reconsideration in Idaho are substantially different from motions for reconsideration under federal law. Under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, there is no rule specifically allowing for reconsideration. That being said, federal courts indicate that motions for reconsideration are generally permitted and have cited F.R.C.P. 59 and 60 as bases of authority for such motions.[iii] In addition, federal courts often cite to their inherent authority to reconsider interlocutory rulings, despite the lack of specific authority.[iv]

The difference in authority leads to entirely different purposes for a motion for reconsideration in Idaho state courts and federal courts. In Idaho state courts, motions for reconsideration have long been utilized as a method to present new evidence.[v] “A rehearing or reconsideration in the trial court usually involves new or additional facts, and a more comprehensive presentation of both law and fact. Indeed, the chief virtue of a reconsideration is to obtain a full and complete presentation of all available facts, so that the truth may be ascertained, and justice done, as nearly as may be.”[vi]

At the same time, “a motion for reconsideration need not be supported by any new evidence or authority.”[vii] “The purpose of a motion for reconsideration is to reexamine of the correctness [sic] of an order.”[viii] Thus, a motion for reconsideration can be used to present new facts, or simply can be used to argue that the law was applied incorrectly. As discussed in the following, though, there are limitations on these purposes.

In contrast, motions for reconsideration in federal courts are much more limited in scope. “[A] motion for reconsideration should not be granted, absent highly unusual circumstances, unless the district court is presented with newly discovered evidence, committed clear error, or if there is an intervening change in the controlling law.”[ix] Ninth Circuit caselaw also suggests that motions for consideration may be appropriate if the initial decision was manifestly unjust.[x]

Despite the limited scope of motions for reconsideration, Idaho’s federal courts have noted, “Ultimately, it is the court’s duty to secure the just, speedy, and inexpensive determination of every action and proceeding. In certain circumstances, this may mean that a court must reconsider, modify, or even reverse a prior determination.”[xi]

With that background in mind, from here on out, this article focuses on motions for reconsideration in Idaho state courts. It is worth noting that, like the Idaho Rules of Civil Procedure, the Idaho Rules of Family Law Procedure also allow for motions for reconsideration.[xii] There is no directly comparable rule in criminal law.[xiii]

Standards of Review

As noted previously, Idaho’s rules on reconsideration set time limits for motions for reconsideration, allowing such motions to be filed up to 14 days after entry of judgment, or 14 days after any order issued after entry of judgment.[xiv] There are numerous orders, though, for which no reconsideration is permitted.[xv]

Caselaw discussing the applicable standard of review for a motion for reconsideration is somewhat contradictory. The Idaho Supreme Court has stated, “A decision of whether to grant or deny a motion for reconsideration made pursuant to Idaho Rule of Civil Procedure 11(a)(2)(B)[xvi] is left to the sound discretion of the trial court.”[xvii] Under this language, arguably the applicable standard is based on the Lunneborg discretionary standard.[xviii] But the Supreme Court has also stated, “When a district court decides a motion to reconsider, the district court must apply the same standard of review that the court applied when deciding the original order that is being reconsidered.”[xix] Under this caselaw, the applicable standard is whatever standard applied to the original motion, whether it be a question of law, a discretionary standard, etc.

The Idaho Supreme Court has not specifically resolved this dichotomy. Take for example Elsaesser v. Riverside Farms, Inc.[xx] There the Supreme Court states that the standard of review is the same as the standard on the original motion. Later, the Supreme Court states that the denial of reconsideration is subject to an abuse of discretion standard and then finds that the appellant did not address any of the Lunneborg factors.

Under such circumstances, it is difficult to determine which standard applies before the district court. Recent case law suggests a mixed bag as to which standard applies to motions for reconsideration.[xxi] Though there is no clear answer, perhaps the ideal approach is to argue the applicable standard for the underlying motion before the district court, and on appeal, be prepared to argue both the standard of the original motion and address the Lunneborg elements to the extent possible.

"Practitioners should not presume that they can solve all evidentiary errors or failures on reconsideration, because the discretion to disregard or allow untimely declarations is fairly broad."

When a Motion for Reconsideration Is Something Else

Occasionally, in Idaho, motions for reconsideration are treated as something else. This is particularly true when a judgment has been entered. In Dunlap v. Cassia Mem’l Hosp. Med. Ctr., the Idaho Supreme Court noted that reconsideration of a partial summary judgment motion filed after a Rule 54(b) certificate was issued was not valid under (then) I.R.C.P. 11(a)(2)(B), but was instead a motion to amend a judgment under I.R.C.P. 59(e).[xxii] The logic was that once judgment was entered, the partial summary judgment was no longer interlocutory, but was instead final, and therefore only the judgment could be amended.[xxiii]

Similar rulings have occurred in other cases. In Eby v. State, a dismissal under I.R.C.P. 40(c) was deemed a final decision, meaning that reconsideration was not permitted under I.R.C.P. 11.2.[xxiv] And in Agrisource, Inc. v. Johnson, the Idaho Supreme Court indicated the conditions under which successive motions for reconsideration are permitted before they become impermissible (which in the circumstances of that case, the first and second were permissible while the third was not).[xxv] Needless to say, courts have authority to treat mislabeled motions for reconsideration as the proper motion.[xxvi]

New Evidence and Timeliness: Which Wins?

Again, a motion for reconsideration may be utilized for the purpose of presenting new evidence to the trial court. Indeed, the Supreme Court has repeatedly said, “The trial court must consider new evidence that bears on the correctness of an interlocutory order if requested to do so by a timely motion under Rule 11(a)(2)(B) of the Idaho Rules of Civil Procedure.”[xxvii] But while couched in mandatory language, there are exceptions to this rule when the new evidence is not timely submitted.[xxviii]

Under several recent cases, the Idaho Supreme Court has rejected new evidence in a motion for reconsideration due to the evidence being inadmissible for some other reason. For example, in Ciccarello v. Davies, shortly after the plaintiff disclosed its experts, the defendants moved for summary judgment, which was granted in part because the plaintiff failed to submit a required declaration of an expert.[xxix] After oral arguments were made on the motions (but before the ruling was issued), the plaintiff submitted a declaration of an expert.[xxx] Despite this, the trial court granted summary judgment, not mentioning the late declaration.[xxxi] The plaintiff then moved for reconsideration, relying on the declaration as new evidence. The trial court declined to rely on this new evidence as it was untimely.[xxxii]

In upholding the grant of summary judgment, the Idaho Supreme Court noted that a trial court had discretion to disregard untimely declarations.[xxxiii] The Supreme Court explicitly addressed the issue of new evidence on reconsideration, stating, “While this Court has explained that when considering a motion for reconsideration the trial court should take into account any new facts presented by the moving party that bear on the correctness of the order, this rule was not designed to allow parties to bypass timing rules or fail to conduct due diligence prior to a court’s ruling.”[xxxiv]

"Practitioners should also be aware of attempting to misuse reconsideration - such as a belated effort to preserve an issue for appeal - as the courts clearly frown upon the practice."

Similarly, in Summerfield v. St. Luke’s McCall, Ltd., the Supreme Court stated, “The trial court should have the discretion to determine whether it will consider additional evidence in support of a motion for reconsideration, if it is submitted late. Without such discretion, parties can bypass timing rules or fail to conduct due diligence prior to a court’s ruling because the trial court must consider any additional evidence.”[xxxv] To emphasize this point, the Supreme Court stated, “In short, while a motion for reconsideration is a safety valve to protect against legal and factual errors, it is not intended to be a mechanism that encourages tactical brinkmanship or a lack of diligence.”[xxxvi]

The takeaway from Ciccarello and Summerfield should be that the requirement that a trial court “must” consider new evidence on reconsideration is subject to exceptions. When evidence is subject to a timing rule, such as an expert disclosure deadline or a declaration that needed to be attached to a responsive briefing under I.R.C.P. 7(b)(3)(B) or 56(b)(2), the evidence may be excluded on reconsideration in the trial court’s discretion. It makes sense that this rule does not apply to newly discovered evidence. Nevertheless, practitioners should not presume that they can solve all evidentiary errors or failures on reconsideration, because the discretion to disregard or allow untimely declarations is fairly broad.[xxxvii]

Reconsideration and Sanctions

The Idaho Supreme Court recently released a case showing how motions for reconsideration can be misused so substantially as to constitute sanctionable conduct. In BrunoBuilt, Inc. v. Erstad Architects, PA, summary judgment was granted in 2019, but final judgment was not issued until two years later.[xxxviii] Fourteen days after the final judgment was granted, the plaintiff moved for reconsideration of the summary judgment order, “based on new arguments and evidence.”[xxxix] The trial court dismissed the motion for reconsideration, finding it to be, “untimely, lacking in diligence, and improper,” and stating that the plaintiff, “did not challenge the correctness of the Order, but raise[d] new arguments based on law in existence when it originally opposed the [defendants’] summary judgment motion.”[xl]

On appeal, the Supreme Court agreed with the trial court and found the appellate briefing as to reconsideration warranted sanctions against the attorneys. The ruling seems strange at first blush. The timing limits in I.R.C.P. 11.2 were met – the motion for reconsideration was filed within 14 days after judgment was granted. Thus, the motion was not – per the rule – untimely. Further, new evidence and additional authority are the bread and butter of a motion for reconsideration, and both were provided to the trial court. So why was this motion for reconsideration unjustified?

The Supreme Court provided several explanations, most of which seem case specific. However, one takeaway is that “reconsideration serves as a judicial backstop granting the trial court another opportunity to make the right call; however, it does not provide appellants with a fourth strike on appeal.”[xli] What this language suggests is that a motion for reconsideration on the same issues, with the same new arguments and evidence, may have been appropriate if it had been filed shortly after the original ruling granting summary judgment.

Regardless, even though the motion for reconsideration was in line with I.R.C.P. 11.2, and the rule’s purpose, it appears the Supreme Court used its equitable powers to impose sanctions against the attorneys under a theory that approaches the concept of laches.[xlii] In other words, yes, a party technically has 14 days after entry of judgment to file for reconsideration, and yes, a party may always submit new evidence and new legal theories. However, any request for reconsideration that looks like an attempt to preserve a new issue for appeal long after the matter was resolved is not guaranteed the right to reconsideration. Thus, the notion that, “the district court has no discretion to decide whether to entertain a motion for reconsideration”[xliii] appears to have limits.

Conclusion

The purpose of a motion for reconsideration under Idaho law is to ensure the correctness of a ruling, either through the review of new evidence, or reexamination of the law. In utilizing a reconsideration motion, practitioners should be aware of the applicable standard of the underlying motion, and on appeal, also be ready to apply the Lunneborg abuse of discretion standards. Motions for reconsideration cannot always be used to get around timing deadlines – particularly those that go along with summary judgment briefing and expert disclosures – for the simple reason that trial courts have broad discretion in excluding untimely evidence. The Supreme Court has indicated that this discretion appears to trump the requirement to consider new evidence on reconsideration.

Practitioners should also be aware of attempting to misuse reconsideration – such as a belated effort to preserve an issue for appeal – as the courts clearly frown upon the practice. At a minimum, it is a waste of time, money, and judicial resources, and at worst, the behavior can result in sanctions. Therefore, practitioners should examine the motives behind a motion for reconsideration before it is filed to determine if it meets the requirements imposed by Idaho caselaw.

Stephen L. Adams

Stephen L. Adams is Senior Counsel with Gjording Fouser in Boise. He is the Treasurer of the Idaho Association of Defense Counsel and is past president of the Idaho State Bar Appellate Practice Section. He used to have only four children but has fairly recently acquired two cat children and one dog child. He did not plan for this and is slowly accumulating enough pet fur to crochet another pet.

W. Christopher Pooser

W. Christopher (Chris) Pooser is the Office Managing Partner at Stoel Rives’s Boise office, where he maintains an appellate practice. He is a member of the Idaho Association of Defense Counsel and is the co-founder and a past president of the Idaho State Bar Appellate Practice Section.

[i] I.R.C.P. 11.2(b)(1).

[ii] Fisk v. McDonald, 167 Idaho 870, 892, 477 P.3d 924, 946 (2020).

[iii] See, e.g., Sch. Dist. No. 1J, Multnomah Cnty., Or. v. ACandS, Inc., 5 F.3d 1255, 1262 (9th Cir. 1993).

[iv] See, e.g. City of Los Angeles, Harbor Div. v. Santa Monica Baykeeper, 254 F.3d 882, 885 (9th Cir. 2001).

[v] See, e.g., Prescott v. Prescott, 97 Idaho 257, 260, 542 P.2d 1176, 1179 (1975). See also Barmore v. Perrone, 145 Idaho 340, 344, 179 P.3d 303, 307 (2008).

[vi] Coeur d’Alene Mining Co. v. First Nat. Bank of N. Idaho, 118 Idaho 812, 823, 800 P.2d 1026, 1037 (1990).

[vii] Fragnella v. Petrovich, 153 Idaho 266, 276, 281 P.3d 103, 113 (2012).

[viii] Int’l Real Estate Solutions, Inc. v. Arave, 340 P.3d 465, 468 (2014).

[ix] Kona Enterprises, Inc. v. Est. of Bishop, 229 F.3d 877, 890 (9th Cir. 2000).

[x] Sch. Dist. No. 1J, Multnomah Cnty., Or. v. ACandS, Inc., 5 F.3d 1255, 1263 (9th Cir. 1993).

[xi] Hajro v. Sullivan, No. 1:21-CV-00468-DCN, 2022 WL 17362060, at *2 (D. Idaho Dec. 1, 2022) (cleaned up, quoting F.R.C.P. 1).

[xii] See I.R.F.L.P. 503(b).

[xiii] State v. Flores, 162 Idaho 298, 302, 396 P.3d 1180, 1184 (2017) (fn. 1). But see I.C.R. 35(b) (allowing for motions for reductions of sentences).

[xiv] I.R.C.P. 11.2(b)(1).

[xv] I.R.C.P. 11.2(b)(2).

[xvi] Now I.R.C.P. 11.2(b)(1).

[xvii] Van v. Portneuf Medical Center, 147 Idaho 552, 560, 212 P.3d 982, 990 (2009). See also Arregui v. Gallegos-Main, 153 Idaho 801, 808, 291 P.3d 1000, 1007 (2012); Marek v. Lawrence, 153 Idaho 50, 53, 278 P.3d 920, 923 (2012); Rocky Mountain Power v. Jensen, 154 Idaho 549, 554, 300 P.3d 1037, 1042 (2012); Commercial Ventures, Inc. v. Rex M. & Lynn Lea Family Trust, 145 Idaho 208, 212, 177 P.3d 955, 959 (2008); Jordan v. Beeks, 135 Idaho 586, 592, 21 P.3d 908, 914 (2001).

[xviii] Lunneborg v. My Fun Life, 163 Idaho 856, 863, 421 P.3d 187, 194 (2018).

[xix] Int’l Real Est. Sols., Inc. v. Arave, 157 Idaho 816, 819, 340 P.3d 465, 468 (2014). See also Franklin Bldg. Supply Co. v. Hymas, 157 Idaho 632, 339 P.3d 357, 362 (2014); Fragnella v. Petrovich, 153 Idaho 266, 276, 281 P.3d 103, 113 (2012); Marek v. Lawrence, 153 Idaho 50, 53, 278 P.3d 920, 923 (2012).

[xx] Elsaesser v. Riverside Farms, Inc., 170 Idaho 502, 513 P.3d 438 (2022).

[xxi] See, e.g. Fisk v. McDonald, 167 Idaho 870, 892, 477 P.3d 924, 946 (2020); Jackson v. Crow, 164 Idaho 806, 811, 436 P.3d 627, 632 (2019); Brunobuilt, Inc. v. Strata, Inc., 166 Idaho 208, 217, 457 P.3d 860, 869 (2020); Alsco, Inc. v. Fatty’s Bar, LLC, 166 Idaho 516, 524, 461 P.3d 798, 806 (2020).

[xxii] Dunlap v. Cassia Mem’l Hosp. Med. Ctr., 134 Idaho 233, 235–36, 999 P.2d 888, 890–91 (2000).

[xxiii] Id. at 236, 999 P.2d at 891. See also Johnson v. Dep’t of Lab., 165 Idaho 827, 830, 453 P.3d 261, 264 (2019) (explaining Dunlap).

[xxiv] Eby v. State, 148 Idaho 731, 735–36, 228 P.3d 998, 1002–03 (2010).

[xxv] Agrisource, Inc. v. Johnson, 156 Idaho 903, 912–13, 332 P.3d 815, 824–25 (2014).

[xxvi] See, e.g., Golub v. Kirk-Scott, Ltd., 342 P.3d 893, 899 (Idaho 2015).

[xxvii] PHH Mortg. Servs. Corp. v. Perreira, 146 Idaho 631, 635, 200 P.3d 1180, 1184 (2009) (emphasis added). See also Fragnella v. Petrovich, 153 Idaho 266, 276, 281 P.3d 103, 113 (2012) (same); Jackson v. Crow, 164 Idaho 806, 811, 436 P.3d 627, 632 (2019) (same); Fisk v. McDonald, 167 Idaho 870, 892, 477 P.3d 924, 946 (2020) (same).

[xxviii] This makes sense as the case from which this mandatory language is originally drawn does not use the word “must,” but instead uses the word “should.” See Coeur d’Alene Mining Co. v. First Nat. Bank of N. Idaho, 118 Idaho 812, 823, 800 P.2d 1026, 1037 (1990).

[xxix] Ciccarello v. Davies, 166 Idaho 153, 157–58, 456 P.3d 519, 523–24 (2019).

[xxx] Id. at 158, 456 P.3d at 524.

[xxxi] Id.

[xxxii] Id.

[xxxiii] Id. at 162, 456 P.3d at 528.

[xxxiv] Id.

[xxxv] Summerfield v. St. Luke’s McCall, Ltd., 169 Idaho 221, 234, 494 P.3d 769, 782 (2021) (cleaned up, emphasis in the original).

[xxxvi] Id.

[xxxvii] See Cumis Ins. Soc’y, Inc. v. Massey, 155 Idaho 942, 946, 318 P.3d 932, 936 (2014); Arregui v. Gallegos-Main, 153 Idaho 801, 805, 291 P.3d 1000, 1004 (2012); Sun Valley Potatoes, Inc. v. Rosholt, Robertson & Tucker, 133 Idaho 1, 5–6, 981 P.2d 236, 240–41 (1999).

[xxxviii] BrunoBuilt, Inc. v. Erstad Architects, PA, 171 Idaho 928, 528 P.3d 531, 539 (2023).

[xxxix] Id.

[xl] Id.

[xli] Id. at 543.

[xlii] I.e. prejudice caused by delay. See Sword v. Sweet, 140 Idaho 242, 249, 92 P.3d 492, 499 (2004).

[xliii] Fisk v. McDonald, 167 Idaho 870, 892, 477 P.3d 924, 946 (2020).

Everything You Wanted to Know About UM/UIM Policies, But Were Afraid to Read by Michael G. Brady

by Michael G. Brady

I frequently receive calls from members of the Bar asking questions about uninsured motorist (“UM”) and underinsured motorist (“UIM”) policy coverages. After listening patiently to the “background story,” I always ask a simple question: “What does the policy say?” Usually, I am met with silence. After further inquiry, counsel admits that either they have not read the UM/UIM coverage provisions of the policy or, incredibly, they do not even have a copy of the UM/UIM policy. When confronted with these responses, I “suggest” that counsel read the UM/UIM policy, and if they still have questions to call me back.