Author: rmccaw

Latino Learning in Idaho: Far From Equal

Elizabeth Finley

Published November/December 2021

The role of Latino immigrants in Idaho dates back to the early 1900’s when, after the Mexican Revolution, people from Mexico began immigrating to working in mines and agriculture, and building railroads.[1] Today, agriculture is the largest contributor to Idaho’s economy and accounts for 20% of the state’s gross state product.[2] The success of Idaho’s agricultural industry depends on crops being effectively planted, watered, and harvested, and without the help of seasonal migrant and immigrant farmworkers this would be impossible.[3]

In 2018, 85% of Idaho’s Latino population, were of Mexican descent.[4] Some farmworkers immigrate permanently, bringing their families with them.[5] Their children attend school and become part of the fabric of the community.[6] Yet, after years of building the Idaho agriculture industry, the children of Latino immigrants and seasonal migrant workers are still struggling to attain equality in education.[7]

Words from Chief Justice Warren Sixty-four years ago, Chief Justice Warren wrote “it is doubtful that any child may reasonably be expected to succeed in life if he is denied the opportunity of an education. Such an opportunity, where the state has undertaken to provide it, is a right which must be made available to all on equal terms.”[8]

This article will address the history of educational desegregation based on language proficiency and federal education law before looking at a current complaint against an Idaho school district which shows that segregated instruction exists in Idaho and fails to provide the educational equality guaranteed under the law.

Desegregation Cases

The earliest school desegregation case took place nearly a century ago in Lemon Grove California, a small suburban district outside of San Diego.[9] In the summer of 1930, the all-white PTA and school board decided to build a separate and segregated school for the Latino students. And insisted that the Latino students attend this school while the white students were allowed to remain at the regular school.[10]

In Alvarez v. Owen the parents of the Latino children argued that the school board was attempting to segregate their children by not allowing them to attend the same school as their white peers, even though 95% of the students were American citizens. They argued that the board had “no legal right to exclude [. . . the Mexican children] from receiving instruction upon an equal basis [. . .].”[11] The California Superior Court agreed, noting that the Latino children were lawfully entitled to receive equal instruction as the white children under California law.[12] The court demanded an immediate reinstatement of the children.[13]

Early Latino desegregation cases such as Lemon Grove, laid the foundation that equality in education was fundamental to equality in the nation.[14] But, it would take two decades until the Supreme Court would rule on segregation in education.[15] In Brown v. Board of Education the Supreme Court held that separate but equal educational facilities violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.[16]

In 1981, the Fifth Circuit held that when a school failed to provide adequate Language Instruction Educational Programs (LIEP) it discriminated against students whose native language was not English. [17] And a year later, in Plyler v. Doe, the Supreme Court held that denying a public elementary or secondary education to an undocumented person violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.[18]

Thus, under the law, schools must offer equal educational opportunity to all students regardless of race, national origin, or citizenship status; and they must accommodate those students not fluent in English such that those students are able to learn on equal footing as their English-speaking peers.

Words from Justice Brennan Justice Brennan wrote for the majority: “In addition to the pivotal role of education in sustaining our political and cultural heritage, denial of education to some isolated group of children poses an affront to one of the goals of the Equal Protection Clause: the abolition of government barriers presenting unreasonable obstacles to advancement on the basis of individual merit.” [19]

Federal Education Law

Congress solidified the ban on racial discrimination in schools with the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and acknowledged that limited English language proficiency was a barrier to equal educational access with the Bilingual Education Act in 1968.[20] Then, in 1974 Congress passed the Equal Educational Opportunities Act (EEOA) providing that “no state can deny equal educational opportunity on the basis of gender, race, color, or national origin through intentional segregation by an educational institution.”[21]

It provides that intentional segregation includes failing to remove language barriers that prevent participation by non-native speakers, essentially mandating that schools accommodate students by providing adequate resources for students who do not speak English.[22] By including language barriers as intentional segregation the EEOA brought English Learner (EL) students under the wing of Brown.[23]

Federal education law gives discretion to states to implement educational policy.[24] This light touch in many ways is ideal as it allows states and local school districts to respond to needs on a local level.[25] State and local educational institutions are able to set curriculum, providing that the curriculum comply with equal protection and civil rights laws.[26] The constitution granted the Legislative branch the power to make law and the Judicial branch the power to say what the law is.[27] Ultimately though, the state agency regulates the school districts and the local school districts are entrusted to implement procedures that comply with the law.

Wilder School District: A Case Study for the EEOA

In January of 2021, Idaho Legal Aid Services filed a complaint on behalf of four Wilder community members against the Wilder School District with the U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights.[28] The complaint alleges, in part, violations of (1) Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and its implementing regulations, (2) the Equal Education Opportunities Act of 1974, and (3) the English Language Acquisition, Language Enhancement, and Academic Achievement Act, Title III, Part A of the Elementary and Secondary Act of 1965.[29]

Wilder School District (WSD) is a small, majority-Latino district in southwestern Idaho. Agriculture is the primary industry in the area and employs many of the Latinos who live there. In 2020, 69% of Wilder’s 506 total students were Latino, making it the district with the largest percentage of Latino students in the state.[30] English Language Learners (ELL), comprise a third of students at WSD.[31] Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act all Idaho districts are required to provide appropriate education to students whose primary language is not English.[32]

The Complaint and Declarations filed in support of the complaint provides the following timeline and allegations:

In 2016, WSD began using a new program known as “Personalized Learning.” This program made iPads the sole means of instruction for all students in all grades, including ELL students. After the program’s inception it became apparent to the parents of ELL students that the program was not working well for their children. A group of WSD parents, students, and concerned residents began to advocate on behalf of ELL students. The group worried that WSD was not providing adequate instruction to ELL students. The students could not teach themselves independently and needed significant help from teachers. But teachers who voiced concern or offered individual assistance to students were told that they would be looking for work elsewhere if their efforts continued.

During the fall of 2017, about a dozen middle school and high school students were identified as needing ELL instruction and services. Shortly after the start of the school year a newly hired PE teacher was also designated as the district’s ELL teacher. The teacher taught PE in the morning and afternoon but was allotted little or no time to provided ELL instruction.

During the spring of 2018, the staff was notified that students were not receiving legally mandated ELL services. In response, the district directed a classroom aid to assume some of the PE teacher’s PE duties. Students then began to receive some ELL instruction. During the second semester, however, the teacher was placed on leave and the district did not replace her. All ELL instruction ceased.

During the fall of 2018, the district did not renew the previous ELL/PE teacher’s contract and the ELL students received no testing or instruction. The elementary level ELL students were sent to “speak English” with a classroom aid and the middle and high school students were told to buddy up with bilingual students so that the bilingual students could tutor ELL students. Once more, a classroom aid with no ELL certification or instructional experience was supposed to mentor these students.

Also, 7th to 12th grade students identified as ELL were required to spend a certain number of minutes on the “Imagine Learning” (IL) iPad app, an app designed specifically for pre-K to 6th grade students to improve reading skills. No out loud work was done with the program, it was strictly read-and-click. ELL designated students were pulled from class two or three times per week and spent about 20 minutes working with the program and a classroom aid. The only assistance students received with speaking or listening skills was from a classroom aid who had no teaching certification in any subject, let alone ELL. There was no writing component to the IL literacy program. When students needed to write in English, they were instructed to use the Google Translate app to translate their Spanish words to English.

Additionally, the superintendent appointed an elementary school teacher as the ELL coordinator and said that she had provided the necessary ELL training to the WSD staff. The administration sent false emails to the staff regarding these training sessions. However, the coordinator did not provide any ELL training at any point that year. Teachers who attempted to speak out about what was happening were threatened with losing their jobs.

Eventually, the parents received an audience with the school board and were able to voice their concerns. The school board did not help the parents, instead it berated them for bringing their concerns forward.

The parents then investigated the school board election process. The written WSD policy requires the district to file a notice for the nomination and election of school district board members in the newspaper. WSD failed to provide notice as required by the policy; the only notice given to the community was on a single bulletin board at the City Hall. The last election had taken place in 2005.

The parents then took their concerns to the State Department of Education. At the time the State Superintendent, Sheri Ybarra, was running for reelection in the Republican primary against the WSD superintendent, Jeff Dillon. The State Superintendent refused to investigate the complaint, citing a conflict of interest to her reelection campaign. She then referred the parents’ complaint back to the WSD Board. After the return of the complaint to the WSD board the WSD superintendent discovered the names of the individuals who lodged the complaint. Students and parents allege that Dillon retaliated against them by taking recess away, revoking privileges, and threatening expulsion of students and deportation of immigrant parents.

By the end of the 2018-19 school year, many of the veteran WSD teachers had quit or been forced out because they had raised concerns about the IL program and 70% of the remaining teachers in WSD were not credentialed in the subjects they were teaching. Student test scores are illustrative of this effect, with only 20% of K-3 students scoring proficient on a fall reading test, fewer than 20% of high school students scoring proficient in math, and only 48% proficient in English language arts.[33]

The EEOA Applied

The Equal Educational Opportunities Act of 1974 provides in part that “[n]o state shall deny equal educational opportunity to an individual on account of his or her race, color, sex, or national origin, by [. . .] the failure by an educational agency to take appropriate action to overcome language barriers that impede equal participation by its students in its instructional program.”[34]

An “individual” denied an equal educational opportunity may bring a civil action in federal court “against such parties, and for such relief, as may be appropriate.”[35] To be successful, a plaintiff must satisfy four elements: (1) the defendant must be an educational agency, (2) the plaintiff must face language barriers impeding her equal participation in the defendant’s instructional programs, (3) the defendant must have failed to take appropriate action to overcome those barriers, and (4) the plaintiff must have been denied equal educational opportunity on account of her race, color, sex, or national origin.[36]

First, WSD is an educational agency and a Title I school district that receives federal funding; therefore, it must comply with the EEOA.[37] Second, the students are not able to read, speak, listen, and write at a level that will allow for them to understand instruction given in English to a degree necessary to participate equally in educational activities.

The third element of the EEOA test, requiring a showing that the defendant failed to take “appropriate action to overcome those barriers” requires that the educational agency make a “genuine and good faith effort, consistent with local circumstances and resources, to remedy the language deficiencies of their students.”[38] The “appropriate action” language of the statute gives state and local educational agencies latitude in developing programs that would meet the requirements of the EEOA. The Department of Education (DOE) Office of Civil Rights (OCR) applies an analysis devised by the court in Castañeda v. Pickard to determine if a district has complied with the appropriate action requirements of the EEOA.[39]

First, the school must use a sound method “informed by educational theory and recognized by experts,” to teach students. Second, the school’s programs and practices must be “reasonably calculated to implement effectively the educational theory adopted by the school.” Third, the program must produce results that language barriers are “actually being overcome.”[40]

Idaho interprets the first criteria to require that a Language Instruction Educational Program be based upon a sound theory and approach that is proven effective in increasing language proficiency.[41] WSD was using IL as its sole means of instruction for the ELL students. The program did not include a listening, speaking, or writing component. Even if IL is found to be a sound method in ELL instruction, without a speaking, listening, or writing element it is likely not compliant with state or federal regulations.

The second prong provides that the program be implemented with sufficient resources, staff, and space.[42] The US DOE has offered guidance that districts have an obligation to provide necessary staff and if the district provides formal qualifications for that staff, the staff must be qualified or working towards qualification; moreover, a district cannot indefinitely allow staff without qualifications to teach students with limited English proficiency.[43]

Idaho law requires that teachers “shall be required to have a certificate issued under authority of the state board of education, valid for the service being rendered [. . .].”[44] Moreover, under Castañeda “the use of Spanish speaking aids may be an appropriate interim measure, but such aids cannot [. . .] take the place of qualified bilingual teachers.”[45]

In WSD, there were no qualified ELL teachers for at least three school years. In 2017, after receiving a noncompliance notice, WSD employed an ELL teacher, but placed her on administrative leave mid-way through the second semester in 2017 and never replaced her. The only individualized instruction provided to the students was by a classroom aid without a teaching certificate or an ELL certificate. The teacher WSD assigned to be the ELL supervisor in November of 2018 was certified in Social Studies and Spanish, not ELL. He was never trained in ELL instruction. The only professional development WSD offered was when the ELL coordinator (also not ELL certified) sent an email referring him to an ELL website and instructing him to train himself.[46]

By the end of the 2018-19 school year many of the veteran teachers had left the district and 70% of the remaining teachers were not certified to teach the subjects they were teaching. Idaho Law requires that persons who are employed to serve in any elementary or secondary school in the capacity of teacher, are required to have a certificate issued under authority of the state board of education.[47]

The third prong of Castañeda states that if the program fails to produce results showing language barriers are actually being overcome, it fails to constitute appropriate action.[48] Even if the program was implemented in good faith and with sound expectation for success, unless the outcome was a success, the program would not constitute appropriate action.[49] In Castañeda, the program was inadequate in part because the testing of the ELL students was inadequate.[50]

WSD failed to test to measure the program’s progress. Purportedly an entry test existed, however, when the ELL supervisor asked to see the test, he was refused.[51] Thus, there was no baseline to establish performance which could then be used to measure progress. Even if an entry test existed, WSD took no subsequent measures to determine progress. Also, no exit testing existed to establish when and if a student had become English Language Proficient. The lack of testing shows that WSD provided no way of establishing if the program was working. Therefore, WSD has failed to show that actual barriers are being overcome under the third prong of Castañeda.

The fourth requirement of the EEOA speaks to the denial of equal educational opportunities on account of a person’s race, color, sex, or national origin. The court has interpreted the final element of the EEOA to require only a showing of denial of equal opportunity based on race, color, sex, or national origin.[52] Here the complainants have established that the students could not engage meaningfully with IL because they are Spanish speaking Latinos. This is grounds for denial of equal opportunity on race and national origin.

Conclusion

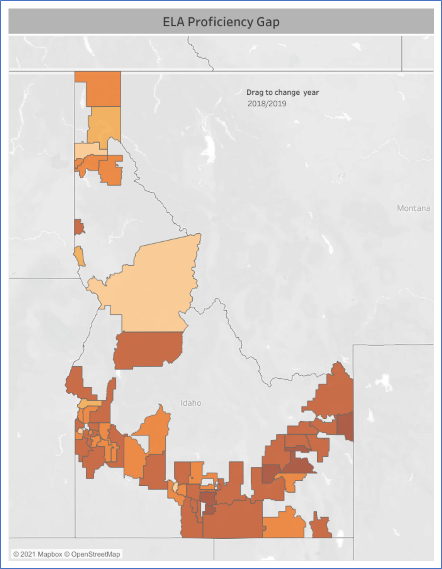

The situation in Wilder, while likely illegal and oppressive, is not uncommon in Idaho.[53] A 2020 investigation into the academic achievement gap between Latino students and white students based on standardized test scores shows disturbing results.[54] Out of 56 districts, 42 had an achievement gap greater than 15%.[55] Many of these districts are located in southern Idaho rural communities where the majority of the Latino population is concentrated.[56]

It has been well over half a century since the landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education, yet Idaho has not honored the intent of the ruling, or subsequent laws passed, to ensure equal educational opportunities for minority students. State and local educational agencies have failed minority students. This failure is most pronounced in Idaho’s rural districts, the same districts which rely heavily on migrant and immigrant workers to ensure their prosperity. It is long past time for Idaho to fulfill its obligation and provide equal educational opportunities for minority students.

“The situation in Wilder, while likely illegal and oppressive, is not uncommon in Idaho.”

Elizabeth Finley is a third-year law student at the University of Idaho College of Law, a Certified Professional Geologist, and a mom of two wild little boys. As an Idaho native raised on a ranch in Owyhee County, she is interested in Idaho policy, civil rights, energy, and natural resources. Liz’s husband and partner of 12 years, Charlie, helps her juggle being a mom and a law student. She enjoys biking, hiking, reading, and hanging with her family.

Endnotes

1 Nicole Foy, ‘We do not like the Mexican.’ Racist chapter of Idaho history revealed by new research, Idaho Statesman (Dec 21, 2019), https://www.idahostatesman.com/news/northwest/idaho/history/article238330788.html

[2] Idaho State Department of Agriculture https://agri.idaho.gov/main/about/about-idaho-agriculture/

[3] Rick Naerebout, Immigrants are vital to Idaho’s dairy industry, Idaho State JournalApril 23,2021. https://www.idahostatejournal.com/freeaccess/immigrants-are-vital-to-idahos-dairy-industry/article_a2ba3496-d9ff-5ad1-bad4-001fa0a3b6bf.html

[4] As defined by the Idaho department of Labor in Hispanic Profile Data Book 5th edition, Idaho Commission on Hispanic Affairs,pg. 39, 55.

[5] Id. at 55

[6] Id. at 110-111

[7] Sami Edge & Nicole Foy, Little accountability for school asked to improve Latino achievement gaps. Idaho ed news.org, Feb. 9, 2020. https://www.idahoednews.org/news/in-high-achievement-gap-schools-plans-for-improvement-are-all-over-the-board/

[8] Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, 493 (1954).

[9] K.L. Bowman, The New Face of School Desegregation, 50 Duke L.J. 1751 (2001).

[10] Robert R. Alvarez, Jr. The Lemon Grove Incident, The journal of San Diego historical society quarterly, Spring 1986, vol. 32, no. 2. https://sandiegohistory.org/journal/1986/april/lemongrove

[11] Id.

[12]Alvarez v. Owen, No. 66625 (Cal. Sup. Ct. San Diego County filed Apr. 17, 1931).

[13] Id.

[14] Robert R. Alvarez, Jr. The Lemon Grove Incident, The journal of San Diego historical society quarterly, Spring 1986, vol. 32, no. 2. https://sandiegohistory.org/journal/1986/april/lemongrove .

[15] Brown, 347 U.S. 483.

[16] Id. at 495.

[17] Castaneda v. Pickard, 648 F.2d 989 (5th Cir. 1981).

[18] Plyler v. Doe, 457 U.S. 202, 210 (1982).

[19] Id. at 222.

[20] Civil Rights Act of 1964, § 7, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e; Bilingual Education Act, 20 U.S.C. § 880b.

[21] The Equal Educational Opportunities Act of 1974, 20 U.S.C.S. § 1703(f).

[22] Id.

[23] ELL students in Idaho are classified according to the Federal government definition as described in the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) Section 3201(5).

[24] U.S. Department of Education, the federal Role in Education, Overview.https://www2.ed.gov/about/overview/fed/role.html

[25] Id.

[26] Idaho content standards English Language Arts/Literacy Manual, pg. 3 https://idahoansforlocaleducation.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/ELA-2018.pdf

[27] U.S Const. art. I, § 1and Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. 137 (1803)

[28] Plaintiff’s Complaint, E.D., C.D., J.D., and J.C., v. Wilder School District. Jan. 27, 2021. https://www.idahoednews.org/news/families-file-discrimination-complaint-against-wilder-school-district/

[29] Id. and 42 U.S.C. §2000d, 34 CFR Part 100, and 28 C.F.R. § 42.104 (b)(2), and 20 U.S.C. §1703(f), 20 U.S.C. §6801

[30] Id.

[31] Id.

[32] Idaho State Department of Education State EL & Title III Program. https://www.sde.idaho.gov/federal-programs/el/files/program/manual/2020-2021-Mini-Manual-State-EL-and-Title-III.pdf

[33] Sami Edge and Nicole Foy, Families file federal civil rights complaint against Wilder district, Idaho Ed News.Org (Jan. 28, 2021)01/28/2021.

[34] 20 U.S.C. § 1703(f).

[35] Id. § 1706.

[36] See 20 U.S.C. § 1703(f) and § 1720(a) (defining “educational agency”).

[37] 20 U.S.C. § 1703(f) and Idaho State Department of Education State EL & Title III program.

[38] Castaneda, 648 F.2d 989, 1011 (5th Cir. 1981).

[39] Internal Department of Ed OCR memo: developing programs for English Language Learners: OCR Memorandum, dated 9/27/1991.

[40] Id.

[41] As laid out by the Idaho State EL & Title III Mini Manual

[42] As laid out by the Idaho State EL & Title III Mini Manual

[43] Internal Department of Ed OCR memo: developing programs for English Language Learners: OCR Memorandum, dated 9/27/1991. https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/ell/september27.html

[44] Idaho Code §33-1201

[45] Castaneda, 648 F.2d at 1013.

[46] Plaintiff’s Complaint, E.D., C.D., J.D., and J.C., v. Wilder School District.

[47] Idaho Code § 33-1201.

[48] Castaneda, 648 F.2d at 1010.

[49] Id.

[50] Id. at 1014

[51] Plaintiff’s Complaint, E.D., C.D., J.D., and E.C., v. Wilder School District, Declaration of CH, pg. 3

[52] Issa v. School District of Lancaster, 847 F. 3d 121, 139 (2017)

[53] Erik Johnson, of Idaho Legal Aid services, attorney for complainants provided that, the DOE is in the process of deciding whether they have jurisdiction over the WSD case. In the meantime, how many more Latino students in need of ELL instruction are marginalized by the lack of an appropriate program at WSD. The school with the largest percentage of Latino students in the Idaho has not had an appropriate ELL program for the past 5 years and counting.

[54] Idaho EdNews Staff, Latino Listening Project wins Education Writers fellowship (Nov. 1, 2019) https://www.idahoednews.org/news/latino-listening-project-wins-education-writers-fellowship

[55] Sami Edge, Maps illustrate learning disparities between white and Latino students (Jan. 3, 2020) https://www.idahoednews.org/news/maps-illustrate-learning-disparities-between-white-and-latino-students

[56] Id.

Gender Designations on Public Identity Documents: To Amend or Abolish?

Casey Parsons

Published November/December 2021

The last several years have marked many victories for transgender people in the United States. In June 2020, the Supreme Court unequivocally held in Bostock v. Clayton County that discrimination against transgender individuals violates Title VII of the Civil Rights Act.[1] One year later, in Grimm v. Gloucester County School Board, the Supreme Court left undisturbed a high school student’s right to use the bathroom when it denied the school board’s petition for a writ of certiorari following a ruling in the Fourth Circuit that favored the student.[2]

Even so, many states – including Idaho – have passed legislation threatening the rights of transgender people. These attacks include prohibitions on accessing medical treatment, bans on trans women in sports, laws that seek to prevent trans and gender non-conforming people from amending their identity documents, and even criminal penalties for transgender people using the bathroom. In some cases, legal remedies have protected those rights. However, in many cases, there is no adequate legal remedy to address the underlying structural conditions that facilitate discrimination against transgender individuals based on their gender identity. The State of Idaho lacks explicit legal protections for transgender individuals and the gap left by federal law subjects trans people in our communities to harassment and discrimination in nearly every aspect of daily life.

As a preliminary matter, it is important to clarify some terms used in this article. One’s presumed sex or gender at birth is the gendered legal and/or medical fiction at the time that they are born. I refer to one’s presumed sex or gender as a fiction because, in many cases, that presumption misidentifies the gender of the individual in question. Moreover, presuming that individuals fall into one of two categories – either male or female – fails to account for the wide spectrum of sex and gender and inappropriately simplifies a complex phenomenon.[3]

The terms “trans” or “transgender” refer widely to individuals for whom the gender presumed at their birth is a misidentification. I use these terms interchangeably, although some people prefer the more inclusive term “trans*.” The term “gender binary” refers to the framework that limits sex and gender to either male or female. Some individuals who are trans identify within the gender binary and are trans men or trans women; others reject that framework entirely and use terms such as “non-binary,” “genderqueer,” or “gender non-conforming.” For the sake of consistency, I will broadly refer to such individuals as either “non-binary” or “gender non-conforming,” but it is important to recognize that neither term captures the full scope of transgender individuals who do not identify within the male-female gender binary.

I also want to address why this issue is so urgent: transgender and gender non-conforming people regularly face violence and discrimination due to their gender identity and expression. In a 2015 survey of transgender individuals, 48% of respondents reported discrimination at private businesses, verbal harassment, or physical attack due to their transgender status within the prior year.[4]

That same survey revealed many other disturbing figures. Among the respondents who held or applied for a job in the last year, 67% reported that they were fired, denied a promotion, or not hired for a job for which they applied due to their transgender status (including, more recently, the author of this article).[5] 23% of respondents reported housing discrimination based on their transgender status.[6] 58% of respondents who interacted with law enforcement reported experiencing verbal harassment and/or physical or sexual assault as a result.[7] And the Human Rights Campaign reported at least 37 instances of fatal violence against transgender people in 2020 – a record-breaking figure.[8] These realities on all counts are particularly acute for transgender people of color.[9]

The present article focuses on courts and state legislatures that have recently allowed non-binary and gender non-conforming individuals to designate their gender as “X” on identity documents; however, even as a starting point that framework is inadequate. Many non-binary or gender non-conforming individuals do not construe their sex or gender as a third category to male and female but instead view gender as a site of experimentation and multiplicity.

I argue that such policies ultimately put trans and gender non-conforming people at significant risk of violence and discrimination. Legislatures should instead consider removing gender and sex markers from identification documents entirely – a policy supported by the American Medical Association.[10]

I argue that such policies ultimately put trans and gender non-conforming people at significant risk of violence and discrimination.

As a quick aside, I feel that it is necessary to address a few common arguments made by individuals opposed to the legal recognition and social acceptance of transgender people. Some argue that transgender people, and trans women in particular, seek access to spaces that align with their gender for predatory reasons. This rhetoric mirrors the anti-gay panic prevalent in the 1990s and early 2000s and has no grounding in empirical data.[11] Moreover, the fact that some individual might take advantage of the gendered framework prevalent in the United States is not a reason to think that states should deny rights to transgender people systematically.

Others contend that biological sex is an objective and sound metric for evaluating one’s identity, and that transgender people are a small and inconsequential anomaly. As noted previously, biological sex is simply too complicated to reduce to a determination that individuals fall into the category of either male or female.[12] Parents and medical professionals often make an arbitrary determination at birth that imposes a particular gender that misidentifies the individual in question. While it is difficult to approximate the population of transgender and gender non-conforming people in the United States, recent reports estimate that 1 in 250 adults is transgender.[13]

Still others argue that the basis for the existence of transgender people is rooted variously in post-modern jargon, identity politics, and queer theory. Proponents of this argument are rarely able to define these terms coherently. Many theorists who seriously contemplate gender reject identity as a foundational basis for politics and instead seek to understand the reality faced by transgender people based on material and class conditions, particularly Dr. Judith Butler.[14] This relatively obscure literature has little bearing on the identity of transgender people, most of whom come out due to the fundamental incongruence between their identity and the experience of socialization based on their misidentified sex or gender at birth.

The first person to gain legal recognition in the United States as a non-binary person was James Shupe. In 2016, Shupe filed a lawsuit in Oregon state court seeking to amend his legal gender from female to non-binary. The state court granted his request.[15] Shupe was a transgender woman at the time but has since decided to detransition and live out his life as a man. Even so, his legal success in Oregon state court was the basis for a petition filed by Dana Zzyym in the Federal District Court of Colorado.

Zzyym sought to apply for a passport but was unable to do so because the only options for the gender designation on the document were male or female, which did not accurately describe their sex or gender. The State Department denied Zzyym a passport on that basis. Zzyym’s legal challenge alleged that the Department’s policy regarding gender markers on passports exceeded its statutory authority and was arbitrary and capricious. The District Court agreed with Zzyym and struck down the policy.[16] On appeal, the Tenth Circuit held that the State Department’s decision to deny Zzyym’s passport did fall within its statutory authority, but that its decision to deny Zzyym’s passport in this case was indeed arbitrary and capricious and remanded the case.[17]

At the time of this article, only 10 states permit one to designate their gender as “X” on public identity documents.[18] 48 states permit one to change their gender between male and female, although the burden placed upon the individual varies widely.[19] 18 states either have no written policy regarding amending gender designations, or they impose an onerous process on those seeking to amend their legal documentation requiring proof of surgery, a court order, and/or an amended birth certificate in order to change one’s designation on their driver’s license.[20] Such requirements rely on an institutional knowledge that is disproportionately inaccessible to transgender communities. Few states allow transgender and gender non-conforming people total autonomy with respect to these documents, which creates significant barriers to transgender people who desire legal recognition for personal or safety reasons.

In 2018, Lambda Legal filed suit against Idaho officials because the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare did not permit transgender individuals to amend their birth certificate to reflect their gender identity. The Idaho Department of Health and Welfare conceded that its policy was unconstitutional and attempted to compromise by offering to implement a policy that would allow transgender individuals to amend the sex designation on their birth certificates, but in doing so the amended birth certificate would contain the revision history as to the listed sex or name. The Federal District Court of Idaho permanently enjoined both policies, reasoning that the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare already permitted applicants to amend other aspects of their birth certificate without the new document disclosing the revisions; for example, amendments to paternity or adoptive status are kept confidential.[21]

The court recognized transgender people as a quasi-suspect class such that courts must apply intermediate scrutiny under the Equal Protection Clause to rules discriminating against them. Because the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare already provided a process to amend one’s birth certificate without disclosing the revision history, the court determined that the proposed policy failed intermediate scrutiny review. In response, the legislature enacted a bill during the 2020 legislative session that would prevent one from altering the gender on their identity documents at all. The Federal District Court of Idaho again enjoined this law based on the prior order.[22]

Currently in Idaho, amending the gender designation on one’s birth certificate requires a trans person to submit an application to the Bureau of Vital Records and Health Statistics and pay a $20 application fee – in addition to a $16 certificate fee for the amended birth certificate. Changing the gender designation on one’s driver’s license requires that the birth certificate be amended and an affidavit from a physician certifying that the applicant has undergone a “change of sex.” The Idaho Transportation Department does not presently define what it means to have undergone that process. There is currently no process in Idaho to amend one’s identity documents to reflect anything other than male or female.

In some cases, the efforts of states and courts to create a process for legally recognizing trans and gender non-conforming people may be well intentioned. Even so, as noted earlier in this article, documents that publicly identify someone as transgender can subject one to fatal violence or facilitate discrimination in nearly every facet of social life. The reliance on policy proposals to allow transgender people to amend their legal documentation also reinforces antiquated gender norms that we should reject.

Transgender women who successfully amend their identity documents to reflect their gender are expected to perform their femininity to be socially accepted. Transgender men must similarly perform masculinity, and non-binary and gender non-conforming people must perform androgyny. To be frank, it is difficult to understand why one’s gender is the business of complete strangers.

In short, a simple and viable alternative exists to these multifaceted requirements to amend the gender designation on one’s public identity documents: legislatures should act to remove such gender designations entirely. They serve little purpose and including them only puts transgender and gender non-conforming people at an increased risk for discrimination and violence from any party that has reason to examine those documents. Doing so would ensure uniformity across states as opposed to imposing different and complicated requirements on transgender people. Moreover, removing gender designations would be in line with the public policy underlying the decision to remove race designations from public birth certificates.[23]

Given the hostile rhetoric and violence levied against transgender people in the state of Idaho, it is no wonder that many of us do not feel safe in this community. There are many steps that readers of The Advocate might take to support transgender people. Readers can demand policies in their workplace prohibiting discrimination against employees and applicants on the basis of transgender status. They can advocate for anti-discrimination laws that apply to housing and businesses at the level of state, county, and city governments. Legal workers can provide low cost or pro bono legal representation when such acts of discrimination do occur. And, perhaps most importantly, readers can organize against and resist the inevitable next piece of legislation proposed to the Idaho House and/or Senate that seeks to further marginalize transgender people.

“In some cases, the efforts of states and courts to create a process for legally recognizing trans and gender non-conforming people may be well intentioned.”

Casey Parsons is a staff attorney with Idaho Legal Aid Services, Inc. in Boise, Idaho. They were born and raised in Idaho Falls and graduated from the University of Idaho College of Law in May 2020. They are passionate about providing accessible legal services and hope to remain in Idaho to fulfill their commitment to building a safer and more inclusive community. They are particularly grateful to Michelle Collazo Vos, Ritchie Eppink, David Losinski, and Mikay Parsons for their invaluable contributions to this article.

Endnotes

[1] Bostock v. Clayton Cnty., Georgia, 140 S. Ct. 1731, 1737, 207 L. Ed. 2d 218 (2020).

[2] Gloucester Cnty. Sch. Bd. v. Grimm, No. 20-1163, 2021 WL 2637992, at *1 (U.S. June 28, 2021).

[3] C. Ainsworth, Sex Redefined, 518 Nature 288, 288-291 (2015).

[4] S. E. James et al., Nat’l Ctr. for Transgender Equal., The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey 198 ( 2016).

[5] Id. at 148.

[6] Id. at 176.

[7] Id. at 185.

[8] Hum. Rts. Campaign Found., An Epidemic of Violence: Fatal Violence Against Transgender and Gender Non-Confirming People in the United States in 2020 (2021).

[9] S.E. James, et al., Nat’l Ctr. for Transgender Equal., Black Trans Advoc. & Nat’l Black Just. Coal., 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey: Report on the Experiences of Black Respondents (2017).

[10] Russ Kridel, American Medical Association, Removing the Sex Designation from the Public Portion of the Birth Certificate 12-16 (2021).

[11] Amira Hasenbush et al, Gender Identity Nondiscrimination Laws in Public Accommodations: A Review of Evidence Regarding Safety and Privacy in Public Restrooms, Locker Rooms, and Changing Rooms, 16 Sexuality Rsch. and Soc. Pol’y 70, 70–83 (2019).

[12] C. Ainsworth, Sex Redefined, 518 Nature 288, 288-291 (2015).

[13] Esther L. Meerwijk & Jae M. Sevelius, Transgender Population Size in the United States: A Meta-Regression of Population-Based Probability Samples, 107 Am. J. of Pub. Health 1, 1-8 (2017).

[14] Jules Gleason, Judith Butler: ‘We Need to Rethink the Category of Woman’, The Guardian (Sept. 7, 2021, 06:14 PM), https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2021/sep/07/judith-butler-interview-gender.

[15] In the Matter of Jamie Shupe, No. 16CV13991 (Or. Cir. Ct. June 10, 2016).

[16] Zzyym v. Pompeo, 341 F. Supp. 3d 1248, 1261 (D. Colo. 2018), vacated and remanded, 958 F.3d 1014 (10th Cir. 2020).

[17] Id. at 1034.

[18] Russ Kridel, American Medical Association, Removing the Sex Designation from the Public Portion of the Birth Certificate 14 (2021).

[19] Id. at 15.

[20] Identity Document Laws and Policies, Movement Advancement Project, https://www.lgbtmap.org/equality-maps/identity_document_laws (last visited Sept. 30, 2021).

[21] F.V. v. Barron, 286 F. Supp. 3d 1131, 1145 (D. Idaho 2018), clarified sub nom. F.V. v. Jeppesen, 466 F. Supp. 3d 1110 (D. Idaho 2020), and clarified sub nom. F.V. v. Jeppesen, 477 F. Supp. 3d 1144 (D. Idaho 2020).

[22] F.V. v. Jeppesen, 477 F. Supp. 3d 1144, 1151 (D. Idaho 2020).

[23] Russ Kridel, American Medical Association, Removing the Sex Designation from the Public Portion of the Birth Certificate 14 (2021).

Critical Race Theory and Workplace Diversity Efforts

Bobbi K. Dominick

Published November/December 2021

Across the country, debates about “critical race theory” (CRT) are raging in legislatures, school boards and organizations, and in diverse locales. While it may seem like a “passing fad,” or cultural hot button issue, diversity practitioners and leaders should pay close attention. Now is the time to reexamine the most effective, and defensible, strategies that will continue to advance diversity despite these cultural debates.

What is Critical Race Theory?

“Critical race theory” is a tool, traditionally used in academia, to analyze historical racism and its impact on institutions and systems, not individual discrimination.[1] Critics have re-defined the term and used it to attack a wide variety of what they view as social ills.[2] These critics seek to characterize the study of racism as discrimination against Whites. The debates are accusatory and divisive. Critics have characterized the theory as “un-American.”[3] Those CRT critics are waging a battle to eradicate it in schools, organizations, and places where CRT does not really exist. In its broadest sense, these opponents of CRT equate it with diversity. Because of this debate, CRT has been villainized and attacked at the highest levels of government.[4] The debate has, and may continue to, impact diversity initiatives.

How Has the Controversy Over CRT Impacted Diversity Initiatives?

Many organizations advance diversity in numerous ways, including through diversity committees, or establishing recruiting, promotion, retention, and training policies that promote diversity. Organizations also mandate supervisory or employee training that promotes respectful treatment and prohibits discriminatory behavior. Some of these training programs (also required to protect against discrimination claims) include topics like privilege, bias, and similar issues.

The first real impact of the CRT debate took aim at these diversity training programs. Former President Trump took up the CRT banner and issued Executive Order (EO) 13950 on September 22, 2020.[5] That order prohibited federal agencies and contractors from conducting training containing purported CRT concepts.

Agencies, organizations, and practitioners had to immediately decide what actions might violate the order. While there is still controversy over exactly what should and should not be taught in diversity training,[6] certain topics seemed to be prohibited by the EO. For example, one expert theorized that the following changes were likely required under the EO:[7]

Terms like “white privilege” should be “scrubbed” from training language. Teaching about privilege is one way that diversity trainers have tried to demonstrate that hidden privilege may hamper inclusion efforts. For example, trainers might talk about advantages some have had, and how race, gender, or other factors might have influenced situations, as a way to help learners recognize that privilege may result in a form of subtle bias.

Training around unconscious or implicit bias was apparently prohibited by the EO. Unconscious bias training, while some view it as potentially ineffective,[8] had become a staple of many diversity trainers. As humans, we all have inherent biases that derive from the way our brains take “shortcuts,” and perceive the world around us, based on who we are, how we were raised, influences we have been subjected to, etc. These biases help us to live and function every day.[9] Some implicit biases could cause us to behave in ways that are prejudicial to other humans, whether because of the way they look, the class they belong to, or our presumptions about how they will behave. While there is some question about whether we can “train away” implicit bias, the first step, and the one included in many types of diversity training, is to make everyone in a workplace aware that implicit bias exists and invite people to explore and examine their own biases. As people become aware, they may take steps to avoid problem behaviors, like assuming that a person of color will act or think a certain way.

Unconscious bias training, while some view it as potentially ineffective,[8] had become a staple of many diversity trainers.

Nearly immediately, diversity experts reported that the EO was having an impact on whether they could deliver meaningful diversity training in federal agency and contractor settings.[10]

Lawsuits challenged this EO[11] in the fall of 2020.[12] In one case, the court granted a nationwide injunction preventing enforcement of EO 13950.[13]. One suit alleged that agencies were prevented from effectively addressing “harms, privileges, and disadvantages associated with systemic discrimination and implicit biases.”[14]

On January 20, 2021, President Biden issued an Executive Order rescinding the prior EO.[15] While this was a relief for federal diversity experts, it also meant that legal questions about the impact of the CRT debate on diversity training were never resolved.

Systemic discrimination has existed in our history and this debate has shone a critical light on some of our national legal history around discrimination, including the Dred Scott decision, where the U.S. Supreme Court concluded that Blacks “had for more than a century before” the Constitution’s adoption “been regarded as beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations; and so far inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.”[16] Other reported decisions from our early legal history reveal outdated notions of racial and gender superiority.[1

While court cases over the last century have subsequently disavowed the discriminatory attitudes reflected in these opinions, members of the protected groups have sometimes continued to face societal discrimination and are still often subjected to hostile work environments. A quick reading of the most recent news briefs issued by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission will demonstrate that individual workplace discrimination remains alive and well.[18]

Efforts by organizations over the last few decades to eliminate such discriminatory attitudes have included the creation of diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging (DEIB) initiatives that create a respectful workplace for all and encourage all workers to eliminate bias in their interactions with co-workers. Those efforts were in doubt, and challenged, by EO 13950, which prohibited any type of training that would cause individuals to feel “discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress on account of his or her race or sex.”

The events of the fall of 2020, and the continued raging debate over CRT, demonstrates that there is a potential for the controversy to significantly change the way that diversity initiatives are created and implemented.

Continued Debate Around CRT Will Reach Organizations and Associations

In 2021, efforts to use CRT as a basis for state legislation began in earnest. In most cases, the focus was upon allegations that CRT was taught in public schools. Many legislatures, including Idaho, passed legislation prohibiting such teaching.[19]

In addition, organizations of various sizes have been rocked by controversy related to diversity and inclusion, as debates over race and discrimination continue.[20]

Christopher Rufo, a principal proponent of “banning” CRT in schools, the military, and organizations, has taken aim at several large organizations (including Disney, American Express, Bank of America, Verizon)[21] which support, and train on, diversity and inclusion, labelling them as “CRT proponents.” Legislators have begun openly advocating that “diversity, equity, inclusion” are new terms for CRT.[22]

What Should Organizations, Including Legal Organizations, Do About CRT and Diversity?

Many research studies show that diversity makes good business sense.[23] This is especially true when organizations focus on recruiting diverse candidates, or training to encourage respectful workplaces, but also most often when business goals are tied to inclusivity and diversity.[24] In the legal profession, one effort is spearheaded by Diversity Lab, which seeks to boost diversity through innovation, data, and behavioral science. Several Idaho firms (multistate) have been recognized for their efforts in promoting inclusion and diversity by receiving a Diversity Lab Mansfield Rule 4.0 certification. (Holland & Hart; Perkins Coie; Stoel Rives).[25]

Idaho, in particular, is less diverse than other legal markets. But the most recent census figures tell us that some parts of Idaho are becoming more diverse,[26] so Idaho legal organizations must examine their hiring, promotion, and inclusion practices if we are to welcome diversity. The most recent Bar survey on diversity of race/ethnicity (from 2016) reveals that the Bar remains overwhelmingly White, measured at 94.21%.[27]

Idaho firms should look to some of the suggestions in the next section if diversity is a desired value for the Bar[28] and for individual organizations we serve.

How Should Diversity Practitioners Respond to the CRT Debate?

The concern for diversity practitioners is that continuation of the CRT debate could eventually impact diversity initiatives within workplaces. Employees who follow the debate could challenge or question the content of diversity training or practices. Efforts to hire diverse candidates could be challenged, by arguments that such efforts adversely impact a particular race (white), and thus are themselves discriminatory. Practitioners should anticipate such debates, and those who advise organizations should encourage critical examination of hiring, promotion, and training practices to assure that the practices used are sound and defensible.

Here are some examples of where the CRT arguments might impact legal practice:

Disparate impact discrimination claims. At least one federal judge has pointed to CRT as a reason for eliminating the disparate impact theory of racial discrimination.[29] If organizations use any sort of statistical analysis to make changes, based on an assumption that practices may be adversely impacting a particular class of people, they should closely examine whether the analysis is defensible.

Reverse discrimination claims. The debate suggests that practices which promote diversity are perceived by some as having a discriminatory impact on Whites. We may see a rise in claims that an organization’s efforts to increase diversity are a form of reverse discrimination.

How Should Organizations Respond?

Organizations, including legal organizations, should also closely examine their diversity practices, to assure that the practices are serving their intended purpose, and are effective. Here are some examples:

Effectiveness and content of training. Many organizations have implemented training around a respectful workplace and diversity. Those training programs are needed, and may be helpful, but some programs may stray too far, using techniques and practices that are not proven to be effective, and may be counterproductive. Many organizations may include discussions of privilege and of implicit bias.

Those are important to include if the goal is to raise awareness, but the way the issues are presented is important, and follow-up is important.[30] Those topics are not designed to be a “one and done” in practice, but many organizations use them in that way. Training may be most effective if the concepts are incorporated into leadership systems, leadership training, and business goals. In addition, the research may show that training, and behavior expectations, for behaviors like bullying, disrespect, and incivility may have a better outcome for diversity.[31]

Hiring and promotional practices. Use of techniques to encourage benchmarks for considering potential candidates that meet diversity criteria can help increase diversity within hiring and promotional classes. But care must be used to assure that candidates are not favored solely based on their diversity, lest reverse discrimination claims arise.

Business goals that include diversity and inclusion lens. Research has consistently shown that diversity increases within an organization, and is most effective, only when DEIB efforts are intertwined within the business goals of the organization.

Employ techniques to interrupt implicit bias within organizations.Experts have identified many different kinds of techniques to assure that diverse candidates have a level playing field when it comes to hiring, legal assignments and development, promotion, etc. Many of those techniques in the legal field are detailed in an ABA report. [32]

There are many other areas where critical examination, research, and discussion may be necessary to assure that the legal profession,[33] legal organizations, and the organizations we advise, are encouraging diversity and inclusion in ways that are truly effective. The current cultural debates over CRT should not deter an increased focus on assuring opportunity for all.

BIO

Bobbi K. Dominick is a sole practitioner in the employment law arena through conducting workplace investigations, respectful workplace training, and providing expert testimony in the area of discrimination and harassment prevention. She is an author of nationally published books Preventing Harassment in a #MeToo World (2018) and Investigating Harassment & Discrimination Complaints (2003).

Bobbi K. Dominick is a sole practitioner in the employment law arena through conducting workplace investigations, respectful workplace training, and providing expert testimony in the area of discrimination and harassment prevention. She is an author of nationally published books Preventing Harassment in a #MeToo World (2018) and Investigating Harassment & Discrimination Complaints (2003).

Endnotes

[1] Jacey Fortin, Critical Race Theory: A Brief History, N.Y. TIMES, July 27, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/article/what-is-critical-race-theory.html?searchResultPosition=2

[2] Such critics are numerous, but they include The Legal Insurrection Foundation, which has made CRT a showpiece of their cultural attacks, see https://criticalrace.org/, and Christopher Rufo, who has championed the theory that CRT is evil and must be eliminated, see https://christopherrufo.com/the-truth-about-critical-race-theory/.

[3] See, for example, Joy Pullman, It’s Critical Race Theory That Is Un-American, Not Laws Banning It, THE FEDERALIST, located at https://thefederalist.com/2021/07/07/its-critical-race-theory-that-is-un-american-not-laws-banning-it/.

[4] See, e.g., Charles M. Blow, Demonizing Critical Race Theory, N.Y. TIMES, June 13, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/13/opinion/critical-race-theory.html?searchResultPosition=1

[5] The EO is no longer in official federal documents but is archived at https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/presidential-actions/executive-order-combating-race-sex-stereotyping/

[6] See, e.g., Ilana Redstone, Diversity Training and Divisiveness: A Real Problem That Needs a Better Solution, FORBES, October 15, 2020 https://www.forbes.com/sites/ilanaredstone/2020/10/15/its-time-to-fix-diversity-training-part-1/?sh=36219f09da04 and Ilana Redstone, This is Why Diversity Programming Doesn’t Work, FORBES, November 18, 2020, https://www.forbes.com/sites/ilanaredstone/2020/11/18/this-is-why-diversity-programming-doesnt-work/?sh=7da8298566d5.

[7] Kenneth Hein, Legal Expert Unpacks What Trump’s Executive Order on Diversity Training Means for Agencies, September 29, 2020, THE DRUM, https://www.thedrum.com/news/2020/09/29/legal-expert-unpacks-what-trump-s-executive-order-diversity-training-means-agencies

[8] See, e.g., Michelle M. Duguid & Melissa C. Thomas-Hunt, Condoning Stereotyping? How awareness of stereotyping prevalence impacts expression of stereotypes, J. Applied Psychology, 2005, https://content.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Fa0037908.

[9] See Project Implicit, located at https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/

[10] Jessica Guynn, ’It’s Already Having a Massive Effect’ Corporate America Demands Trump Rescind Executive Order on Diversity, USA TODAY (October 9, 2020) https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/2020/10/09/trump-rescind-diversity-racism-executive-order/5939538002/

[11] National Urban League v. Trump, Case 1:20-cv-03121 (D.C.D.C. 10.29.20) https://d12v9rtnomnebu.cloudfront.net/paychek/1_-_Complaint.pdf

[12] See, e.g., National Urban League above.

[13] Santa Cruz Lesbian and Gay Community Center et. al v. Trump et. al., Case No. 5:2020cv07741 (N.D. Cal. 12/22/2020) https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/california/candce/5:2020cv07741/368312/80/

[14] Santa Cruz, paragraph 4.

[15] Located at https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/01/20/executive-order-advancing-racial-equity-and-support-for-underserved-communities-through-the-federal-government/

[16] Dred Scott v. Danford, 60 U.S. 393, 404-407(1857).

[17] See Johnson & Graham’s Lessee v. M’Intosh, 21 U.S. 543, 590 (1823) (referring to Native Americans as “fierce savages, whose occupation was war and whose subsistence was drawn chiefly from the forest”); Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537, 561 (1896) (Harlan, J., dissenting) (noting that Chinese people are “a race so different from our own that we do not permit those belonging to it to become citizens of the United States”); Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475, 479-80 (1954) (noting that Mexican-American children were in segregated schools, restaurants had signs saying ‘No Mexicans Served,’” and that “[o]n the courthouse grounds . . . , there were two men’s toilets, one unmarked, and the other marked ‘Colored Men’ and ‘Hombres Aqui’ (‘Men Here’)”). See also Bradwell v. Illinois, 83 U.S. 130 (1872) (Supreme Court refusing to recognize a woman’s right to practice as an attorney, citing “a maxim of that system of jurisprudence that a woman had no legal existence separate from her husband, who was regarded as her head and representative in the social state” and that the “paramount destiny and mission of women are to fulfill the noble and benign offices of wife and mother.” Cases also reflect past societal contempt for the LGBTQ community, as noted in Bowers v. Hardwick, 478 U.S. 186 (1986).

[18] Located at https://www.eeoc.gov/newsroom/search

[19] See Idaho Code §33-138.

[20] Elizabeth A. Harris, In Literary Organizations, Diversity Disputes Keep Coming, NEW YORK TIMES, August 30, 2021,https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/30/books/diversity-literary-rwa-scbwi.html

[21] See Rufo’s Twitter feed at https://twitter.com/realchrisrufo. Rufo also tweeted that he is working on a series “exposing” CRT in “America’s Fortune 100 companies.” https://twitter.com/realchrisrufo/status/1430626870450540544. Rufo’s attack on organizations can be found in various articles, https://www.city-journal.org/verizon-critical-race-theory-training?wallit_nosession=1 (Verizon); https://christopherrufo.com/bank-of-amerika/ (Bank of America) and https://www.city-journal.org/bank-of-america-racial-reeducation-program?wallit_nosession=1; https://nypost.com/2021/08/11/american-express-tells-its-workers-capitalism-is-racist/. (American Express)

[22] See tweet at https://twitter.com/MikeLoychik/status/1431387748984836097

[23] See, e.g., Diversity Wins: How Inclusion Matters, MCKENZIE & COMPANY (May 19, 2020) located at https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/diversity-and-inclusion/diversity-wins-how-inclusion-matters

[24] Also see, e.g., Together Forward at Work: The Journey to Equity and Inclusion, SHRM (Summer 2020) located at https://prodtfw.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/20-1412_TFAW_Report_FNL_Pages_V2.pdf

[25] See explanation of the criteria and list of qualifying firms here: https://www.diversitylab.com/mansfield-rule-4-0/

[26] For example, the 2020 Census indicates that Boise’s White population is now only 62% of the total population, a reduction of 32% in the last 30 years. See https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/interactive/2021/racial-makeup-census-diversity/?geoid=16001002319.

[27] Statistics drawn from 2016 Idaho State Bar Membership Survey, located at https://isb.idaho.gov/wp-content/uploads/2016_isb_membership_survey.pdf. That survey is five years old (a new survey may be planned for 2021) but it indicates that most other ethnic/racial categories hover around +1% of the attorney population. Statistics regarding diversity in the legal profession can be found here: https://www.americanbar.org/groups/diversity/resources/goal3-reports/demographic_trends_in_the_legal_profession/.

[28] For example, recent studies of EEO-1 reports in large corporations indicated deep underrepresentation of Black and Hispanic representatives in the legal industry. See Jessica Guynn and Jayme Fraser, This is America: Black and Hispanic workers are still not getting a fair shake at work, USA TODAY (September 3, 2021) https://www.usatoday.com/story/opinion/2021/09/03/black-hispanic-employees-corporate-diversity-george-floyd/5715025001/

[29] See Rollerson v. Bravo River Harbor Navigation District of Brazoria County Texas, Case No. 20-4027 (5th Cir. 7/29/2021); see also Debra Cassens Weiss, Federal appeals judge criticizes disparate impact theory; are his opinions op-ed columns? ABA JOURNAL (August 5, 2021) https://www.abajournal.com/news/article/federal-appeals-judge-criticizes-disparate-impact-theory-are-his-opinions-op-ed-columns

[30] See, e.g., Joelle Emerson, Don’t Give Up on Unconscious Bias Training-Make It Better, HARVARD BUSINESS REVIEW, April 28, 2017, https://hbr.org/2017/04/dont-give-up-on-unconscious-bias-training-make-it-better

[31] See, e.g., Lim, S., & Cortina, L., Interpersonal mistreatment in the workplace: The interface and impact of general incivility and sexual harassment. JOURNAL OF APPLIED PSYCHOLOGY, 90(3), 483-496 (2005). http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.3.483

[32] Many techniques for interrupting bias are included in an ABA report titled You Can’t Change What You Can’t See, ABA Commission on Women in the Profession. That report is available only for purchase at https://www.americanbar.org/products/ecd/ebk/358942050/. See also tools located at https://biasinterrupters.org/toolkits/orgtools/.

[33] Beyond the scope of this article is a discussion of what the Idaho State Bar itself can do to encourage diversity, such as promoting civility and fair treatment. Some Bar organizations have adopted ethical rules in this area, but Idaho has yet to do so. See letter from Chief Justice Roger Burdick, Idaho State Bar Advocate, 61 ADVOCATE 17 (2018). https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.barjournals/adisb0061&i=853.

DisAbility Rights Idaho Collaborates with Idaho Federation of Families to Educate and Empower Youth Accessing Mental Health Services

Kayla M. Steinmann

Published November/December 2021

It should be no surprise that youth mental health in America is at an all-time low. During the pandemic, youths faced social isolation and loneliness. They lost parents and loved ones and were exposed to other traumas such as food insecurity and homelessness. Critical developmental needs went unmet as children were isolated from friends and missing out on typical school activities and milestones. Even pre-pandemic, data indicated that our youth were struggling with increased rates of depression, thoughts of suicide, and self-harm.[1]

Screening data indicates that the population most impacted by the COVID-19 crisis was youths aged 11-17 years old.[2] Now, still in the midst of the ongoing global pandemic, a new analysis suggests that depression and anxiety in youth has doubled compared to pre-pandemic levels, likely instigating a global mental health crisis in youths.[3]

It is in response to this crisis that two Idaho nonprofits have come together to develop support for youth mental health. DisAbility Rights Idaho (“DRI”) is Idaho’s designated protection and advocacy system, with federal and state authority to monitor any facility or service provider in the state providing care or treatment to individuals with disabilities, or to investigate incidents of abuse and neglect of individuals with disabilities.[4] The Idaho Federation of Families (the “Federation”) provides direct family support services for parents and caregivers of youth with mental health challenges and serves youth through programs that focus on peer support and advocacy. Together, these organizations have created a Youth Rights Series as an ongoing resource for Idaho’s youth.

Current State of Youth Mental Health in Idaho

The data in Idaho is bleak. In 2020, Mental Health America ranked Idaho 48th in the nation for youth mental health.[5] The national nonprofit ranked the 50 states and the District of Columbia based on seven measures including youth with at least one major depressive episode (“MDE”) in the past year, youth with an MDE who did not receive mental health services, and students identified with emotional disturbances for an individualized education program.[6]

Idaho ranked 50th for youth with at least one MDE in the past year with 16.22 percent of Idaho youth experiencing an MDE in 2020.[7] The data shows that Idaho youths have been significantly impacted over the past 24 months and Idahoans must build a better support system that equips youth with tools necessary to develop into thriving young adults.

“It is more important than ever to start having conversations about mental health and destigmatizing mental health with youth.”

DRI’s Youth Unit

DRI’s 2020 organizational restructuring now means it has a dedicated youth unit, as well as an adult unit, to address the needs of Idahoans with disabilities. The youth unit focuses on a range of critical issues affecting Idaho’s youth, such as addressing the use of restraint and seclusion in public schools and representing families in Medicaid Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (“EPSDT”) denials. However, most of the youth unit’s work entails protecting the rights of children in residential treatment facilities in Idaho through periodic monitoring and investigations.

Idaho has 25 licensed Children’s Residential Treatment Facilities (“CRTF”).[8] Children in these facilities come from all over the country for a variety of reasons but mainly to receive intensive support for serious emotional and behavioral problems. Deficiencies, abuses, and rights violations are widespread in CRTFs.[9] Some CRTFs are turning million-dollar profits while vulnerable children are physically and sexually abused in their care.[10] As atrocities come to light, states are responding by passing legislation to increase regulation of CRTFs, taking steps to bring kids home from out-of-state placements, and shifting funds to community-based services that better serve youth.[11]

Research and logic both affirm that youth are best served when at home in their communities.[12] DRI believes it is essential to avoid out-of-home placement whenever wrap-around, community-based care could meet the needs of the child and the child’s family. Part of keeping Idaho’s children safe from the abuses of residential treatment means emphasizing preventative care and helping children access mental health treatment in their own communities.

DRI and the Federation seek to Empower Youth to be their own Advocates

The collaboration between DRI and the Federation seeks to address youth access to mental health care from the youth’s perspective. The intention of the Youth Rights Series is to increase youth access to mental health services by educating youth directly on their rights and mitigating some of the hesitations they may have that are fueled by lack of knowledge or misinformation. Studies indicate that the top three most common barriers to youth seeking and accessing professional help for mental health problems are (1) limited mental health knowledge, (2) social stigma and embarrassment, and (3) inability to trust confidentiality in therapeutic relationships.[13]

Teenagers may be unaware of the circumstances under which they can access treatment on their own. They may be unaware of confidentiality standards in sessions and avoid needed therapies because they are afraid of getting in trouble with their parents.[14] Through this series, DRI and the Federation work together to improve young people’s knowledge of mental health problems and available support, including what to expect from professionals and services.

The series features Natalie Perry, the Federation’s youth move coordinator interviewing Kayla Steinmann, DRI’s youth unit attorney and the author of this article, on the legal perspectives that affect Idaho youths’ ability to access mental health services. Together they dissect Idaho and federal laws in a youth-friendly format and encourage youths to access treatment. The project thus far has taken on the subjects of confidentiality in mental health sessions and accessing mental health treatment. Young people can take an active role in seeking help, particularly as they age, and the Youth Rights Series aims to equip them with the knowledge they need to take that control into their own hands.

Idaho needs to mitigate the sustained mental health effects of COVID-19 and prioritize recovery planning now. It is more important than ever to start having conversations about mental health and destigmatizing mental health with youths. If you know youth in your life who would benefit from increased awareness of these issues, invite them to check out the series on either the Federation’s or DRI’s websites or YouTube channels.

Other Idaho organizations concerned with increasing education and awareness of youth mental health issues are the National Alliance on Mental Illness Idaho, Idaho Parent Network for Children’s Mental Health, and Empower Idaho. It is incumbent upon all of us to teach our children that it is okay to ask for help.

Kayla M. Steinmann is an attorney in the youth unit at DisAbility Rights Idaho. She recently graduated from Washington University St. Louis School of Law in 2020. Advocating for the human rights of children is her personal passion and reason for attending law school. She enjoys backpacking, playing the ukulele, and baking pies.

Endnotes

[1] See The State of Mental Health in America 2019, Mental Health Am., 5 (2018) https://mhanational.org/sites/default/files/2019%20MH%20in%20America%20Final_0.pdf; 2020 Mental Health in America – Youth Data, Mental Health Am., https://mhanational.org/issues/2020/mental-health-america-youth-data (last visited Oct. 5, 2021).

[2] 2021 Policy Institute: Addressing Youth Mental Health Needs in Schools, Mental Health Am., https://mhanational.org/2021-policy-institute-addressing-youth-mental-health-needs-schools (last visited Oct. 5, 2021).

[3] Sarah Molano, Youth depression and anxiety doubled during the pandemic, new analysis finds, CNN Health (Aug. 10, 2021), https://www.cnn.com/2021/08/10/health/covid-child-teen-depression-anxiety-wellness/index.html.

[4] See 42 U.S.C. § 10805.

[5] See 2020 Mental Health in America – Youth Data, Mental Health Am., https://mhanational.org/issues/2020/mental-health-america-youth-data (last visited Oct. 5, 2021).

[6] Id. (full data set includes: (1) youth with at least one MDE in the past year, (2) youth with a substance use disorder in the past year, (3) youth with a severe MDE, (4) youth with an MDE who did not receive mental health services, (5) youth with a severe MDE who received some consistent treatment, (6) children with private insurance that did not cover mental or emotional problems, and (7) students identified with emotional disturbances for an individualized education program).

[7] Id.

[8] Children’s Residential Programs Provider List, Idaho Dep’t of Health and Welfare, https://publicdocuments.dhw.idaho.gov/WebLink/DocView.aspx?id=2675&dbid=0&repo=PUBLIC-DOCUMENTS&cr=1 (last visited Oct. 5, 2021).

[9] See Position Statement 44: Residential Treatment for Children and Adolescents with Serious Mental Health and Substance Use Conditions, Mental Health Am., https://www.mhanational.org/issues/position-statement-44-residential-treatment-children-and-adolescents-serious-mental-health (last visited Oct. 5, 2021).

[10] Hannah Rappleye et al., A profitable ‘death trap’: Sequel youth facilities raked in millions while accused of abusing children, NBC News (Dec. 16, 2020), https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/profitable-death-trap-sequel-youth-facilities-raked-millions-while-accused-n1251319.

[11] Shut Down Sequel: Progress Report, Nat’l Juv. Just. Network, 4 (2020) http://www.njjn.org/uploads/digital-library/ShutDownSequelProgressReport_April2021.pdf.

[12] Id. at 7.

[13] Amelia Gulliver et al., Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: a systematic review, BMC Psychiatry (2010) https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-10-113.

[14] Id.

15. Note: DisAbility Rights Idaho (DRI) is the Protection and Advocacy System for the State of Idaho. This article was made possible by funding support from SAMHSA, U.S. Administration for Community Living, Department of Health and Human Services and DOE-Rehabilitation Services Administration. These contents are solely the responsibility of DRI and does not represent the official views of any federal grantor. 100% of this article was paid for with federal funds.

In Honor of Jennifer: Remember to Please Take Care of Yourself and Others

Courtney R. Holthus

Published November/December 2021

On October 31, 2016, the Diversity Section and the Idaho State Bar lost one of its promising members, Jennifer King, to suicide. As the fifth anniversary of her passing approaches, I wanted to take this opportunity on behalf of the Diversity Section to honor her by sharing information and resources to help those who may be feeling hopeless, overwhelmed, depressed, or even in crisis as we continue to trudge through life in the midst of COVID-19.

Jennifer was an active member of the Diversity Section and our Love the Law! Program. I will always remember her sweet, kind demeanor and warm smile. I wouldn’t say we were close friends, but we would see each other numerous times throughout the year. Each time we would talk about our jobs, our career aspirations, and our personal and professional struggles. I distinctly remember her telling me why she wanted to be lawyer: because she wanted to help and serve others. She had a big heart and truly valued our Section’s mission to promote inclusivity and equality in the law.

I think back often to our last interactions. I’ve read and re-read the last email correspondence we had. I honestly had no idea that she was depressed, let alone to the point of taking her own life. I will always wish I could have done something to help her, which is why I have decided to write this article. Perhaps the following information, the organizations, the phone numbers, may help someone else who is struggling during this time.

According to the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare, Idaho had the fifth highest suicide rate in the United States in 2018.[1]