Author: rmccaw

The Future of the Land Grant Law School

Dean Johanna Kalb

Published September 2021

This summer, I had the great honor of taking over the helm of the University of Idaho College of Law. In so doing, I joined a small and special group of deans who have the privilege of leading land grant law schools. In my preparation for the transition, I was surprised at how little has been written about the distinctive identity and mission of these institutions. In my view, this represents a missed opportunity, particularly in this challenging moment in legal education.

In this essay, I provide a brief overview of the unique history of land grant institutions and then describe the ways in which our founding mission should inform our vision at land law schools. I close by highlighting the ways in which we are living our land grant identity at the University of Idaho College of Law and describe some of our plans for the future. [1]

The Past and Present of Law Grant Law Schools

Despite the significance of our land grant institutions, their history is not widely known. [2] In 1862, Congress passed the Morrill Act which gave each state 30,000 acres of land per federal representative for the purpose of creating public universities.[3] At the time, “a college degree was largely obtainable only by wealthy, white, urban males.”[4] Thus, the goal of these new land grant institutions was to begin to democratize access to education “to promote scientific farming, produce skilled labor, foster technological innovation, bolster transportation, and inculcate civic knowledge.”[5]

Because of the Morrill Act’s emphasis on agriculture and engineering, land grant institutions, including the University of Idaho (“UI”), have been leaders in farming innovation and are significant contributors both to our national economy and to managing the world’s food supply.[6]

Our success in the agricultural space has sometimes masked the broader mission of the land grant institutions. The Morrill Act was adopted in the early years of the Civil War when the future of the American democratic experiment was very much in doubt. By making a university education more broadly accessible, Republicans in Congress hoped that these institutions would lay the foundation for more representative, and therefore more effective, leadership for the nation.[7] It should not be surprising, therefore, that universities like ours viewed the opening of law schools as key to their mandate.

Fast forward to the present day, and there are now just under 200 accredited law schools in the United States, a small fraction of which are part of land grant universities.[8] The world of legal education, and higher education more generally, is a challenging place these days. We have faced years of declining financial support[9] and relatedly—a public that is increasingly questioning the value of what we have to offer.[10]

We are being pushed by our accreditors (rightly in my view) to be more accountable for our students’ success on the bar exam[11] and in the job market.[12] And the tyranny of national rankings value, and none of which focus on our relationship with the communities in which we are embedded.

The 21st century law school is being asked to be all things for everyone. The challenge for us is to find and follow a vision that meets the many competing demands of the present moment. But a particular strength of land grant law schools is that our founding mission offers key principles to guide us, even as we learn from and contribute to the national dialogue on legal education.

Access

The first core principle for land grant law schools is access. The mission of the land grant institution was to make higher education available outside of urban elite communities, an inspiring vision that is still being realized. Many of the earliest land-grant institutions were radical not just in their orientation toward “the industrial classes,”[13] but also in that they were among the earliest co-educational universities in the United States.[14]

In 1890, the second Morrill Act banned racial discrimination in land grant institutions but allowed states to meet this obligation by creating “separate institutions ‘of like character.”[15] The result was the establishment of a new group of colleges and universities, primarily in the South, aimed at educating Black Americans.[16]

In 1994, land grant status was extended to 25 tribal colleges and universities, a small step toward providing Native communities with access to the educational system that their ancestral land was used to house and to fund.[17] Subsequent legislation has included funding for some programming at Hispanic-serving colleges and universities.[18]

With formal de jure discrimination no longer a barrier to educational access, the work for land grant institutions has turned to smoothing the path for students who are the first in their families to attend college, and for those from under-represented communities. And this work is more crucial than ever. The complexity of the application process and the skyrocketing costs of tuition have recreated some of the barriers to access that the land grants were founded to overcome.

The average cost of law school tuition nationally has reached approximately $47,000 per year in tuition and fees alone for out of state students at public and private universities.[19] For students without personal or family resources, the law school debt burden can easily reach $200,000.

As I see it, our role in this moment is to model ways to offer a quality education at a price that makes a law degree a smart investment. We can draw on our experience as the original colleges and universities of access to build stronger and more effective pipelines into law school and into the profession. And we can share our histories, as a way of highlighting the transformative effect that democratizing access to education has, not only on our students and their families, but on the leadership and economies of our states.

“As I see it, our role in this moment is to model ways to offer a quality education at a price that makes a law degree a smart investment.”

These commitments do not come without a cost. For example, there is a strong and unsurprising correlation between socioeconomic status and standardized test performance.[20] That means law schools need to make choices between ensuring access and succeeding in the national rankings. Dollars spent (or foregone) to make tuition affordable or to provide additional tutoring and bar preparation assistance cannot be used to support faculty scholarship or upgrade our buildings.

Yet, if we in the land grant law schools give up on these students as too costly to recruit and educate, we are, in my view, losing sight of our special purpose that distinguishes us from all other institutions of higher education and that has made us so transformative in the lives of our students and in the progress of our nation.

Community Engagement

This brings me to the second guiding value: community engagement. Land grants, unlike their private counterparts, were designed to provide education and build research capacity in ways that would provide direct and practical benefits to the nation’s economy. Declining public support for our institutions reflects, at least at some level, a failure either to build effective community partnerships or, more likely, to communicate their successes to key stakeholders and the public.[21]

Fortunately, the trend in law schools over the last few decades has been toward an emphasis on practical or “experiential” education.[22] Law schools are now required to ensure that students build their lawyering skills in addition to learning doctrine, often by representing real clients under faculty supervision in clinics or through externships with legal and business employers. Relatedly, law school faculty are also increasingly engaged in public scholarship, designed to leverage legal theory to solve real-world problems.

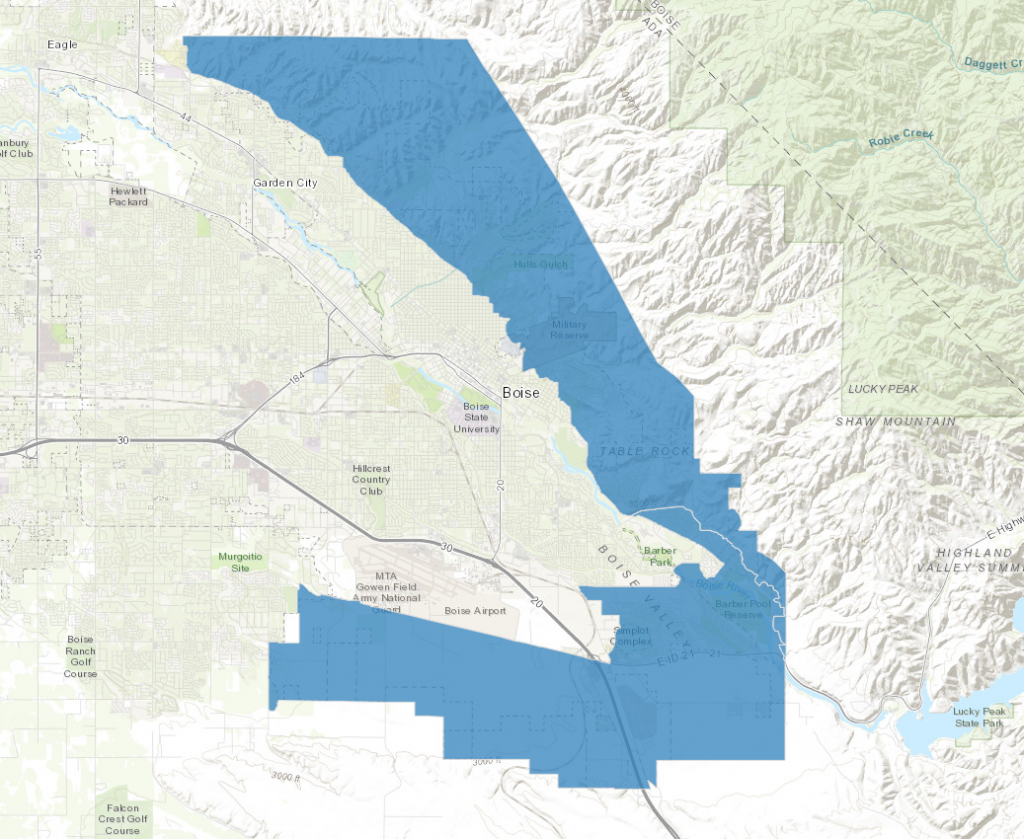

Land grant law schools have real choices to make about how to support and structure these kinds of opportunities, given the wide range of engaging work of interest to students and faculty. In my view, our land grant mission again provides us with guidance about where to invest our resources. Idaho, like most other states, is experiencing a legal services crisis. Half of Idaho’s 44 counties have fewer than 10 attorneys, including those who work for the government. Five of those counties have no private counsel and three have no attorneys at all.[23] For many Idahoans looking to adopt a child, start a business, invest in a piece of land, or draft a will, legal services are simply inaccessible.[24]

Under these circumstances, our founding ideals would suggest that we prioritize providing critical legal services to communities in need in our state, while working with our partners in the bench and bar to develop creative ways to build capacity over the longer-term.

Public Accountability

A final principle that should inform our direction is public accountability, which dovetails with the ideas of access and community engagement. As schools compete for tuition dollars, many students are treated increasingly as consumers rather than beneficiaries of higher education, even at public colleges and universities.

Together with the growing financial burden, this sends the message to students that their investment in higher education is a personal, rather than societal one. This orientation shapes, in both pragmatic and philosophical ways, the decisions that graduates make about how to use their degrees. Paying it back makes it harder to pay it forward. And if the public does not see the graduates of their universities engaged in work to better the lives of people in the state, its support declines, and the cycle continues.

As land grant law schools, our success depends upon reversing these trends and repairing the relationship between ourselves, our students, and the people of our states. Our students should understand the charge and responsibility that comes with being graduates of our special institutions. And, as professional schools, we should work actively to facilitate connections between our graduates and communities in need around the state, so that the public can see the direct benefits of their investment in us.

The Future of Legal Education in Idaho

Fortunately, much is happening in land grant law schools, and particularly at the University of Idaho College of Law, that supports these goals. As an access institution, we have remained committed to controlling tuition prices, with the result that Idahoans can attend the College of Law at half the price of the average law school. With your support, we are working to further defray these costs, most recently through the launch of the Tribal Homeland Scholarship Program, which provides a $10,000 scholarship to successful applicants who are members of federally recognized tribes.

We know too that cost is only one of the challenges that face first-generation and minoritized law students. This year, we have grown our academic success and bar preparation program with the hiring of three new faculty to help ensure that all our students are successful in law school and in their transition to the practice.

Our community engagement prioritizes the needs of Idahoans and our dual campus structure allows us to be present in more ways around the state. Our faculty continues to research solutions to the issues facing our state, from the challenges posed by growth in Boise, to the regulation of teacher certification, to the management of our water resources.

This fall, we will launch our grant-funded Housing Clinic, which will work to address the pressures of rising home prices on Idahoans. This brings us to a total of five in-house clinics, which is impressive for a public law school of our size. We also have a growing externship program, supervised by clinical faculty in Boise and Moscow.

Our new faculty hires arriving this fall will strengthen our Business Law program, which is training lawyers to support our state’s growing economy, and our Native American Law Program, which prepares our students, both Native and non-Native, to serve the tribes’ work in economic development, environmental restoration, and the provision of social services.

Finally, we continue to find ways to be in relationship with the people of Idaho, to highlight our gratitude for their sustaining support, and to instill in our students a commitment to the community that has invested in their education. As part of our mission through the Idaho Law and Justice Learning Center, we host training institutes for teachers and for journalists. We also, in partnership with the Idaho Supreme Court, continue to house and serve the State Law Library in service to the public. And every student who graduates from our law school is required to complete 50 pro bono hours, which helps lay the foundation for a lifetime of service.

Of course, we can and will strive to do better. We will continue to explore new ways to reach first generation students around the state, and facilitate their access to law school, including through expanding our partnerships with Idaho’s other public and private institutions. We hope to expand our presence to better meet the needs of Idaho’s rural communities, guided by students and recent graduates in our Agricultural Law Society. I have heard from so many of you already about your desire to welcome our students into your towns and counties and your willingness to share with them the challenges and the tremendous rewards of lawyering in these places. A goal for me is to find summer funding for students to pursue these opportunities as a way of building their connections with all you.

And we will continue to provide a forum for discussion and debate on issues of interest to Idahoans, fulfilling our unique role as an intellectual community for the residents of our state, and modeling for our students the leadership we expect them to exercise as graduates. For those of you who are alumni of our institution, expect to hear from me – we hope that you will return to our campuses often to share your stories with us and our students.

One of the most attractive qualities of this deanship is the strong connection between the law school and the bench and bar. I understand our status as a land grant law school to mean that your role in visioning the future of Idaho’s legal education is at least as important as mine. I look forward to many conversations and collaborations in the months to come.

Johanna Kalb was appointed to serve as the Dean of the University of Idaho College of Law in May 2021. She is the first woman to serve in tis role. Prior to her deanship, Dean Kalb was the Associate Dean of Administration and Special Initiatives and Edward J. Woman Jr. Distinguished Professor of Law at Loyola University New Orleans School of Law. Her research and teaching interests include constitutional law, federal courts, and the law of detention and democracy. She is a co-author, with Martha F. Davis and Risa Kaufman, of the first law school textbook focused on domestic human rights, Human Rights Advocacy in the United States (West, 2014). Her recent scholarship appears in U.C. Irvine Law Review, the Yale Journal of International Law, the Yale Law and Policy Review, and the Stanford Journal of Civil Rights and Civil Liberties, as well as the Washington Law Review Online, the NYU Law Review Online, and the Yale Law Journal Forum.

From 2014 to 2016, Kalb served as Visiting Associate Professor of Law and Director of the Arthur Liman Public Interest Program at Yale Law School. Dean Kalb is a graduate of Yale Law School and the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies where she completed her M.A. in International Relations with a focus on African Studies. After law school, she served as a clerk for the Honorable E. Grady Jolly of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit and the Honorable Ellen Segal Huvelle of the District Court of the District of Colombia. She is admitted to practice in the States of Mississippi and New York.

Endnotes

[1] I received helpful feedback on this essay from my colleagues Michele Bartlett, Don Burnett, Wendy Couture, Aliza Cover, Benji Cover, Teresa Koeppel, Richard Seamon, and Jodi Walker. Tenielle Fordyce-Ruff and the Advocate Board provided excellent editorial assistance. My views here were informed by conversations with the Justices of the Idaho Supreme Court and the leadership of the State Bar. I am grateful for their time and support of the College. This essay draws on the work of Professor Stephen M. Gavazzi of Ohio State University and President E. Gordon Gee of West Virginia University, whose passion for land grant institutions has helped to inspire my own.

[2] See Stephen M. Gavazzi & E. Gordon Gee, Land Grant Universities for the Future: Higher Education for the Public Good 29 (2018).

[3] U.S. Congressional Research Service, The U.S. Land-Grant University System: An Overview 5 (R45897; Aug. 29, 2019), by Genevieve Croft (hereinafter “U.S. Land-Grant University System”).

[4] See Gavazzi & Gee, supra note2, at 43.

[5] Margaret A. Nash, The Dark History of Land-Grant Universities, Wash. Post (Nov. 8, 2019), at https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2019/11/08/dark-history-land-grant-universities/.

[6] See Gavazzi & Gee, supra note 2, at 38.

[7] The Hartford Gunn Institute, Educational Telecommunications: An Electronic Land Grant for the 21st Century, Current (Oct. 22, 1995), available at http:// www.current.org/pbpb/articles/morrillgunnpaper.html. See also Clifford W. Young, Background for Developing a System of Hispanic-Serving Land-Grant Colleges 3 (undated manuscript prepared for the Hispanic Association of Colleges and Universities), available at http://www.hacu.net/images/hacu/young.pdf (last visited July 11, 2021).

[8] See ABA, List of ABA-Approved Law Schools, https://www.americanbar.org/groups/legal_education/resources/aba_approved_law_schools/ (last visited July 11, 2021).

[9] See Gavazzi & Gee, supra note 2, at 61-62.

[10] Andrew Kreighbaum, Persistent Partisan Breakdown on Higher Education, Inside Higher Ed (Aug. 20, 2019), https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2019/08/20/majority-republicans-have-negative-view-higher-ed-pew-finds.

[11] Janelle McPherson, ABA changes law school accreditation standard because of COVID, National Jurist (Dec. 17, 2020) https://www.nationaljurist.com/national-jurist-magazine/aba-changes-law-school-accreditation-standard-because-covid

[12] See ABA Standard 509, https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/publications/misc/legal_education/Standards/2018-2019ABAStandardsforApprovalofLawSchools/2018-2019-aba-standards-chapter5.pdf (last visited July 11, 2021) (requiring public disclosure on the law school website of consumer information including employment outcomes).

[13] Act of July 2, 1862 (Morrill Act) § 4, PL 37-108 (codified as amended at 7 U.S.C. § 301).

[14] See generally Andrea G. Radke-Moss, Bright Epoch: Women and Coeducation in the American West (2008).

[15] U.S. Land-Grant University System, supra note ii at 6.

[16] Stephanie Y. Brown, Land Grant Universities and Access in the Millennium: A Mandate to Re-Capture Service Opportunities in Under-Represented Communities, 13 U.D.C. L. Rev. 219, 222 (2010).

[17] See Nash, supra note iv. See also Robert Lee & Tristan Ahtone, Land-Grab Universities, High Country News (Mar. 30, 2020).

[18] U.S. Land-Grant University System, supra note 3, at 1.

[19] Ilana Kowarski, 10 Most Expensive Law Schools, U.S. News (Jun. 7, 2021), https://www.usnews.com/education/best-graduate-schools/the-short-list-grad-school/articles/most-expensive-law-schools.

[20] See Letter From Society of American Law Teachers to Maureen O’Rourke, Chair, ABA Section on Legal Education and Admission to the Bar re: Statement in Support of Eliminating the Standard 503 Requirement that Every Prospective Student Submit a Standardized Admissions Test Score (Mar. 31, 2018), https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/legal_education_and_admissions_to_the_bar/council_reports_and_resolutions/comments/20180331_comment_s503_salt.pdf. LSAT scores also vary tremendously by racial group, with Blacks and Latinos scoring lower than Whites and Asians. Marisa Manzi & Nina Totenberg, ‘Already Behind’: Diversifying the Legal Profession Starts Before the LSAT, NPR.org, (Dec. 22, 2020), https://www.npr.org/2020/12/22/944434661/already-behind-diversifying-the-legal-profession-starts-before-the-lsat. It should perhaps unsurprising, therefore, that law is the least racially diverse profession in the country. Id.

[21] See Gavazzi & Gee, supra note 2, at 27-31 (describing the communication challenges land-grant university leaders have in communicating the value of these institutions to their different constituencies).

[22] See generally Peter A. Joy, The Uneasy History of Experiential Education in U.S. Law Schools, 122 Dickinson L. Rev. 551 (2018).

[23] This analysis was performed by Michele Bartlett of the University of Idaho College of Law in 2020.

[24] See also Stephanie L. Kane, Monica Reyna & Barbara E. Foltz, Legal Needs Assessment: SSRU Technical Report 12-08-20 (March 2013) (presenting comprehensive survey data on the unmet legal needs of Idahoans with household income below the statewide median).

Tradition and Change at the University of Idaho College of Law

Richard H. Seamon

Published September 2021

As I write this, less than a month remains before the University of Idaho College of Law welcomes its incoming class, the Class of 2024. I invite attorneys reading this to recall what law school class they were in. I was Class of 1986 myself and, perhaps like you, vividly remember the feelings of excitement, anxiety, and self-doubt that predominated on the eve of law school. I suspect that these eve-of-law-school feelings are shared by every incoming class since the College of Law opened its doors more than 110 years ago. Some things don’t change.

In contrast, the College of Law itself has changed in many significant ways since then. This issue highlights some of those changes.

Let us start with most exciting one: the College is blessed with a new dean, Johanna Kalb, who as of May 2021 succeeded the College’s former dean, Jerry Long, in whom the College was also blessed. Just in her short time on the job, Dean Kalb has infused the College with new energy and ideas. And, as Dean Kalb’s article shows, that energy will be channeled—and those ideas will be informed—–by an understanding of the distinctive duties of a land grant law school. In this way, change will be rooted in worthwhile, longstanding traditions.

The duties of a land grant law school, as Dean Kalb writes, include productively engaging with all the communities that a land grant law school serves; giving students practical knowledge and skills; and addressing access-to-justice challenges. All three duties are carried out in major ways by the College’s legal clinics, which are the subject of three other articles in this issue.

John Hinton writes about the Entrepreneurship Law Clinic, which is based in Boise and vitally connected to the Treasure Valley’s incredibly vibrant business community. This clinic gives students valuable transactional lawyering skills and serves startups and other small businesses in need of legal services.

Geoff Heeren describes the Immigration Clinic, which is based in Moscow and gives students valuable experience aiding an underserved community of clients in a growing area of legal practice.

Finally, Jessica Long describes the involvement of the College’s Main Street Law Clinic in lengthy, complex litigation on behalf of the needy residents of the Syringa Mobile Home Park outside Moscow. The litigation offered hands-on experience to more than two dozen law students, who also had the opportunity to collaborate with skilled attorneys in the Idaho bar.

Professors Hinton, Heeren, and Long have built upon the unsurpassable work of Professor Emeritus Maureen Laflin, recipient of the Idaho State Bar’s Distinguished Lawyer Award in 2020. Although the award reflects a career of many outstanding accomplishments, it would have been merited even if one considered only Maureen’s role in solidifying and expanding the College’s legal clinics. In large part through Maureen’s efforts, the clinics have become the crown jewel of the College’s experiential-learning curriculum. They continue to shine.

“There is a silver lining to this still-dark cloud.”

To stay with the subject of recent changes at the law school, many of those changes over the last year have been necessitated by the COVID-19 pandemic. There is a silver lining to this still-dark cloud. As a practical matter, it has forced the College to expand its proficiency with online technology, along with its capacity to serve our large, still relatively sparsely populated State. More to the point, as I try to show in my piece for this issue, the pandemic has demonstrated the continuing relevance and dynamism of the U.S. Constitution. One can be an originalist while still appreciating the extent to which that document was “intended to endure for ages to come,” and to which, as reformed by its 27 amendments and interpreted by the U.S. Supreme Court, it has “adapted to the various crises of human affairs.”[1]

The College is grateful for the opportunity to host this issue. On behalf of the College and my co-authors, I thank the Idaho State Bar, with special thanks to Tenielle Fordyce–Ruff, Jessica Harrison, Brian Kane, Elizabeth Mathieu, Diane Minnich, Kenny Shumard, and Zach Zollinger. I also thank those who have read this far, and to them I say: Don’t stop now; keep reading!

Richard H. Seamon is a professor at the University of Idaho College of Law who teaches constitutional law and other subjects. He welcomes your feedback at richard@uidaho.edu.

[1] McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 U.S. 316, 415 (1819) (emphasis in original).

A State of Equilibrium

Kristin Bjorkman Dunn

Idaho State Bar Commissioner

Fourth District

Published September 2021

I live in a neighborhood where one of the streets ends with a cul-de-sac in front of a park. It is a quiet space and an ideal location to learn how to ride a bicycle. Recently I was on an evening walk with my son and as we passed through the cul-de-sac, we saw a family using the space for that exact purpose. The child sitting astride the bicycle was young, maybe four years old and was pedaling with determination as an adult ran alongside holding the seat of the bicycle until the child balanced and sped off without further assistance. My son recalled that he learned to ride his bicycle in the same cul-de-sac. I told him his older sister did too.

As I watched the child pedal round and round in the cul-de-sac, I thought how mastering the balance necessary to ride a bicycle would open a new dimension in the world of this child. Riding solo builds independence and provides a means to explore one’s surroundings. I also reflected on the myriad ways seeking and finding balance plays a regular role in our lives. In our early years, balance is integral in our quest to learn to walk. Later, as with the child I saw in the cul-de-sac, balance helps us master the bicycle. Balance, however, it not just confined to our physical movement. Balance plays a role in other ways too.

We balance the need to belong, to feel part of a community, against our individual uniqueness. As students we balance our time between play and study. When we enter the work force, we balance the hours spent at our trade with the responsibilities we have at home. We strive for balance between time dedicated to work and time spent in relaxation. We make space for friends and family.

Balance factors into other elements of our lives. For example, our health benefits from a balanced diet. Financial security is improved with a balanced portfolio. Balance of power protects us from tyranny. Individual freedom is balanced with public order and safety. When we balance our desire to be heard with the importance of listening to others we become better partners, better parents, and better citizens and relationships flourish.

” It was also a reminder that without balance our movements are clumsy, our priorities become skewed, and our communities lack harmony.”

Just as it is in these other contexts, balance is at work in the law. Lady Justice holding the Scales of Justice is one of the most, if not the most, recognizable symbols in the legal system. The scales might not always rest in perfect balance, but they represent that evidence for and against an issue should be weighed and considered. Attorneys are distinctly aware of the importance of objective evaluation and critical thought. We understand that balanced consideration of the issues is an important component of finding a solution. We use these abilities regularly in our work. We balance the view of our cases against the merits of the other party’s position. We seek to help disputing parties find mutual understanding. When asked to write contracts, we provide guidance to our clients helping them sort through the details and address individual concerns while balancing the need for common ground with the other party.

Seeing that child in my neighborhood was a sweet moment. It was also a reminder that without balance our movements are clumsy, our priorities become skewed, and our communities lack harmony. I suspect the balance found by the child I saw in the cul-de-sac required more than one try. It’s not all that different when you are an adult.

Growing up, Kristin Bjorkman Dunn lived in several parts of Idaho. She called the the towns of Salmon, Burley, and Moscow home. When she was finished with school, Kristin’s first job took her to Coeur d’Alene. Kristin now makes her home in Boise. In her spare time she can be found reading on her back patio, running on the greenbelt, or camping with her family.

The Impact of Discrimination, Harassment, and Bullying on Lawyers in Idaho

Catherine A Freeman

Gregory B. LeDonne

Jodi A. Nafzger

Cathy R. Silak

Published October 2021

Several years ago, our Idaho State Bar (“ISB”) membership faced some internal division over whether to adopt a rule that would require lawyers to refrain from discriminatory and harassing behavior in certain instances. Through these discussions, some members questioned whether the rule sought to fix a problem that did not exist: Do Idaho lawyers experience harassment and discrimination?

At that time, there was a lack of objective and quantifiable data about whether—and to what extent—our fellow ISB members were experiencing these types of negative behaviors. To answer this question, the Anti‑Discrimination Anti‑Harassment Committee (the “Committee”), a committee of the ISB Professionalism & Ethics Section (the “P&E Section), decided to embark upon the first Idaho professional climate survey: the Climate of The Legal Profession in Idaho 2020 Survey (the “Survey”).

Simply put, the Survey results illustrate an uncomfortable truth: discrimination, harassment, and bullying are pervasive in Idaho’s legal community. 2 in 5 active ISB members surveyed have experienced discrimination, 1 in 4 have been harassed, and 2 in 5 have been bullied in their legal career in Idaho.[1] Female attorneys experience these behaviors to a disproportionate degree; 50% of our female ISB colleagues have been harassed, 50% have been bullied, and 75% have experienced discrimination.[2]

We cannot dismiss these behaviors as anecdotal and perception‑based. Do Idaho lawyers experience harassment and discrimination? Yes, and at rates that should alarm and concern each of us.

Thankfully, the Survey results also create an opportunity for positive change. Now that ISB members are aware of the issue, we are empowered to take action. Below, this article will provide background on the Survey and detail the results. From there, it will explore ways for all of us to help combat discrimination, harassment, and bullying in Idaho’s legal community.

Background on the survey

The goals of the Survey were threefold: (1) to understand whether a problem of discrimination, harassment, and/or bullying exists within Idaho’s legal community; (2) to provide an anonymous platform to report such problems; and (3) to explore possible solutions. With the support of the ISB Commissioners, the P&E Section engaged the services of the Idaho Policy Institute (the “IPI”) to develop the Survey. The IPI is staffed by Boise State University faculty, staff, and students. The staff provides research and evidence-based practices to meet critical community needs, including for government entities.[3] The IPI generously provided its professional expertise free of charge.

“According to the Survey results, discrimination, harassment, and bullying impact most of Idaho’s lawyers in some fashion.”

The P&E Section provided input on the Survey components and questions and the ISB Commissioners also reviewed and approved the questions and approved distribution of the Survey to the ISB’s membership via email. The Survey was open for a 2-week period in July 2020. IPI faculty and graduate students then summarized the data findings into an Executive Summary and detailed narrative. The Survey results were provided to the ISB Commissioners in November 2020. The ISB Commissioners approved publication of the results in April 2021, following some amendments requested by 3 of the 5 Commissioners and executed by the IPI.

All active members of the ISB had an opportunity to participate in the Survey. Of the 6,323 members, there were 909 partial responses and 682 completed responses, yielding about a 14% response rate.[4] The Survey authors indicated that a survey population the size of the ISB’s membership needed a minimum of 601 responses to reach a confidence level of 99% with a 5% margin of error.[5] The number of responses exceeded that threshold so the Survey had a 99% level of confidence, meaning that 99 out of 100 samples from the ISB’s membership would produce a similar result.[6]

The confidence level produced in the Survey response indicates the data is not random; rather, the data accurately reflects the attitudes of the ISB membership as a whole.[7] The United States Census Bureau, for instance, routinely uses confidence levels of 90% in its population estimates.[8] To summarize, the results of the Survey can be trusted, and are representative of the climate of the legal profession in Idaho as a whole.

In addition, the demographics of the respondents appears to correlate closely with the demographics of the ISB membership overall.[9] The respondents were 55% male and 38% female, with a majority indicating that they were heterosexual (83%) and Caucasian (82%).[10] Only a small portion of the total number of respondents identified as non‑binary (less than 1%), bisexual (3%) or homosexual (2%), or from any of the following categories: Hispanic or Latino, Asian Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaskan Native, and African American (2% or less of each).[11] The respondents were most commonly in the 37‑49 years age range (35%), but the ages of respondents were distributed relatively evenly among the age group categories in the Survey.[12]

Based on the above demographics, the Survey results focus on the relationship between gender and discrimination, harassment, and bullying.[13] While the data set prevents us from performing any intersectional review, it is important to acknowledge that a number of personal characteristics, such as age, ethnicity, sexual orientation, could have their own individual and potentially compounding effect on the issues raised by the Survey.

Survey results

According to the Survey results, discrimination, harassment, and bullying impact most of Idaho’s lawyers in some fashion. However, as mentioned above, the ISB’s female members experience each at statistically higher rates than their male counterparts.[14] A majority of our female membership—nearly 3 out of every 4 women—have experienced discrimination, most commonly based on sex/gender, and approximately 1 out of every 2 female members have experienced harassment and bullying.[15] In comparison, approximately 1 out of 6 men have experienced discrimination, 1 out of 8 have been harassed, and 1 of 3 have been bullied.[16]

Sex/gender discrimination is far and away the most common form of discrimination experienced by Idaho’s female attorneys (93%).[17] In contrast, men most commonly experience discrimination based on religion (45%) and secondarily based on sex/gender (37%).[18]

Few attorneys experiencing discrimination reported the discrimination to an authority: only 16% of women and 18% of men.[19] Fear of repercussions for themselves was the most common reason given for not reporting.[20] Respondents were also asked if they had witnessed discrimination against others. 60% of women reported that they had, compared with 34% of men.[21]

The Survey results highlight a stark comparison between the female and male respondents’ experiences of being harassed. More than half of the female respondents have been harassed, but only 13% of the male respondents have.[22] The most commonly reported forms of harassment were as follows: unwelcome remarks, jokes, or using offensive slang terms; unwelcome acts of aggression, intimidation, hostility, or unequal treatment; unwelcome sexual remarks or jokes, sexual advances, propositions, or requests for sexual favors; and acts of aggression, intimidation, hostility, or unequal treatment based upon an individual’s protected class.[23]

Only 22% of males and 22% of females responded that they had reported the harassment, giving reasons such as fear of repercussions, the status of the person who engaged in the harassment, and not wishing to revisit the incident.[24] Women and men both reported witnessing the harassment of others, with approximately 46% of women reporting this and 25% of men.[25]

Almost half of the respondents have been bullied in the practice of law in Idaho, including approximately 54% of female and 35% of male respondents.[26] In addition, a number of individuals—48% of women and 34% of men—have witnessed other people being bullied.[27] The most commonly reported forms of bullying were ridicule or demeaning language, misuse of power or position, implicit or explicit threats, and overbearing supervision or undermining.[28]

The attorneys surveyed indicated that the workplace and the courtroom are the most common places where they experience discrimination, harassment, and bullying.[29] Both men and women reported that they experienced harassment and discrimination at the hands of their managers and supervisors, but they most commonly experienced bullying from their colleagues.[30] However, it is uncommon for either men or women to report incidents of bullying—only 23% of men and 23% of women reported.[31]

The results of the Survey should be concerning to all ISB members and leaders. Notably, more than half of the ISB members in this state have been negatively and directly impacted by discrimination, harassment, and/or bullying. Many individuals will likely find the results of the Survey unsurprising since such a significant number of us have either been the target of or witnessed these negative behaviors. The results provide empirical validation to these individuals’ experiences and show that discrimination, harassment, and bullying are commonplace occurrences in Idaho’s legal profession.

Plans to combat discrimination, harassment, and bullying in Idaho’s legal profession and call to action

As previously mentioned, these results also create an opportunity for positive change. In fact, the individuals surveyed exhibited positive responses to a slew of offered solutions. The solutions that were most desirable to the respondents were as follows: (1) buy‑in from senior leadership to make a change regarding the culture of the profession; (2) ISB providing model policies for discrimination, harassment, and bullying; (3) improved avenues of reporting and better enforcement of policies that address discrimination, harassment, and bullying; (4) ISB recommending or providing a standardized training regarding discrimination, harassment, and bullying; (5) change in voluntary civility standards; and (6) change in the Idaho Rules of Professional Conduct.[32]

Based on the results of the Survey and the request for change from the ISB membership, the Committee has begun to increase education for the ISB membership. The Committee has already provided several CLEs on these issues and is currently planning future CLEs. Additionally, the Committee will strive to host at least one CLE per year in the P&E Section’s lunchtime meetings regarding discrimination, harassment, and bullying. Hopefully, through education, we can help prevent any members of our legal community from facing these issues.

In addition, because the Survey showed that some members desire a rule change to address discrimination, harassment, and bullying in the Idaho Rules of Professional Conduct, the Committee is actively drafting an amendment that it intends on proposing to ISB membership this year.

The issues outlined in the Survey results are not unique to the legal profession or to Idaho. However, as the Idaho Rules of Professional Conduct highlight, attorneys are both officers of the legal system and public citizens having special responsibility for the quality of justice.[33] Because of this, we should be leaders in fostering a legal community that is safer, more respectful, and more inclusive than found elsewhere.

Incidents of these negative behaviors have often been—and continue to be—dismissed as anecdotal and perception‑based. However, the data support the contentions of many: we as a profession need to do better. We encourage each of you to stand up against discrimination, harassment, and bullying; to elect leaders who recognize that these issues are widespread and who are committed to addressing them; and to continue learning about these negative behaviors, their impact on the legal profession and our fellow ISB members, and ways to combat them.

Thank you to the 909 individuals who participated in the Survey. We commend your bravery in sharing your experiences, and we hope this is the first step toward a lasting and positive change in our legal community.

Cathy Silak is a member of Hawley Troxell’s Litigation practice group and focuses on Idaho and

Federal appellate practice and dispute resolution. She began her career with Hawley

Troxell in 1984 and became partner in 1988. From 1989 to 1990 she was Associate

General Counsel of Morrison Knudsen. In 1990 Cathy was appointed by Governor

Cecil D. Andrus as the first woman judge on the Idaho Court of Appeals. She was

appointed in 1993 to the Idaho Supreme Court and became the Court’s Vice-Chief

Justice in 1997. She served on the Supreme Court until 2000, and in 2001 she

resumed her partnership with Hawley Troxell. After serving as the Founding Dean of

Concordia University School of Law, Idaho from 2008-2016, Cathy became Concordia

University’s Vice President of Community Engagement. Cathy has practiced law in California and Washington D.C., and was appointed an Assistant United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York. She also served as a Special Assistant United States Attorney for the District of Idaho.

Jodi Nafzger is the Director of Experiential Learning and Title IX Coordinator at the College of Idaho. Previously she was a founding faculty member at Concordia University School of Law where she taught Criminal Law, Criminal Procedure, Evidence, and Professional Responsibility. She also served as a temporary faculty member at the University of Idaho College of Law. Jodi is a former Assistant City Attorney for the Boise City Attorney’s Office and legal advisor to the police department. Jodi received a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Missouri-Columbia School of Journalism and a Juris Doctor from the University of Missouri-Columbia School of Law. Jodi is a member of the Idaho State Bar’s Professionalism & Ethics Section and the Anti-Discrimination and Anti-Harassment Committee. She also serves on the Board of Directors for Idaho Women Lawyers and the Idaho Council on Domestic Violence and Victim Assistance.

Catie Freeman is a trial lawyer with Gjording Fouser. Catie is the current Secretary of the P&E Section, the current chairperson of the Section’s Anti‑Discrimination Anti‑Harassment Committee. Catie is also a member of Idaho Women Lawyers and currently serves as the Past President of the University of Idaho Alumni Association.

Gregory B. LeDonne is an attorney and historian. He formerly worked as a prosecutor and government attorney in Boise.

Endnotes

[1] Climate of the Legal Profession in Idaho at 15.

[2] Id. at 3‑4.

[3] Idaho Policy Institute, Boise State University, https://www.boisestate.edu/sps-ipi/.

[4] Climate of the Legal Profession in Idaho, 2020, at 4, https://isb.idaho.gov/wp-content/uploads/Climate-of-the-Legal-Profession-in-Idaho-2020.pdf.

[5] Climate of the Legal Profession in Idaho at 5.

[6] Id.

[7] See id.

[8] See United States Census Bureau, “A Basic Explanation of Confidence Intervals,” https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/saipe/guidance/confidence-intervals.html.

[9] See id., see also Idaho State Bar Membership Survey at 1‑3.

[10] Climate of the Legal Profession in Idaho at 6‑7.

[11] Id. at 7.

[12] Id.

[13] Id. at 6.

[14] Id. at 4.

[15] Id. at 7 & 9‑10.

[16] Climate of the Legal Profession in Idaho at 7 & 9‑10.

[17] Id. at 7.

[18] Id.

[19] Id. at 8.

[20] Id. at 76‑77.

[21] Id. at 8.

[22]Climate of the Legal Profession in Idaho at 9.

[23] Id.

[24] Id. at 10.

[25] Id.

[26] Id.

[27] Id.

[28] Climate of the Legal Profession in Idaho at 10.

[29] Id. at 8‑9 & 11.

[30] Id. at 4.

[31] Id. at 11.

[32] Id. at 82.

[33] Idaho Rules of Prof’l Conduct preamble (Id. Bar Ass’n 2017).

How to Deal with a Dead Party in a Live Case

Stephen L. Adams

Published October 2021

Every so often, we as attorneys must deal with the unfortunate fact that our client, whether a plaintiff or a defendant, has passed away. This is often a very sad fact for the families of the decedent, and as an attorney, we are tasked with playing both counsel and counselor.

However, the emotional minefield is not the only place where we need to step lightly; we also have to make sure we apply the law correctly, as the law changes significantly when your client is no longer living. This article will provide some considerations that should be addressed when dealing with a deceased client in a lawsuit.

Differences and similarities between a deceased plaintiff and a deceased defendant

A deceased plaintiff and a deceased defendant are vastly different things. In some respects, there are similarities, as the attorney needs to determine what claims and damages or defenses transfer from the decedent to a substitute party. However, as discussed below there are many differences.

Who should be bringing or defending the lawsuit depends on when the decedent passes away, and whether the claim that inspires the lawsuit was the cause of death. If the plaintiff or defendant is alive at the time the lawsuit is filed, they personally are likely the proper party to bring/defend the suit.[1]

Who is the proper defendant for a civil lawsuit?

If a defendant passes away before the lawsuit is filed, then the person probably most proper to be served is the representative of the defendant’s estate.[2] If there has been no personal representative appointed at the request of the decedent’s family or friends, other steps can be taken to make sure a person with standing can fill the role of defendant. For example, if there is no one who wants to act as personal administrator for the estate, a special administrator can be appointed purely for the purpose of dealing with the lawsuit.[3]

Typically a motion is filed with the Court to appoint the special administrator. This motion will explain why a special administrator is desired over a personal representative and will ask that the special administrator’s duties be limited to dealing with the lawsuit. While a family member or friend is likely ideal to fill the role of special administrator, if the defendant has no family or friends, there is no legal requirement indicating that the person acting as special administrator have any special relationship with the decedent.[4] Any attorney representing the decedent in a civil action should take care to look for conflicts that may arise should the attorney also represent the estate/probate generally.

The timing for appointing a personal representative for a defendant also matters. It is often the case that an estate is not timely opened by a family member or friend, and that an attorney hired to defend the estate in a civil action does not have access to someone who is willing to fill the role as personal representative or special administrator. Under such circumstances, the plaintiff, as a creditor of the estate, may seek to have themselves appointed as personal representative.[5] This can cause significant confusion and complexity.

“For a deceased plaintiff, the question involves not only when the plaintiff dies, but what caused the death and what type of claims exist.”

If this happens in insurance defense cases, the attorney hired to represent the deceased defendant may end up representing the plaintiff, who has been appointed the personal representative. This creates significant conflicts. The best way to avoid this situation is to find a personal representative or special administrator to be appointed to address the lawsuit before the plaintiff files a petition to be appointed. This may mean seeking to appoint someone who has no limited connection to the decedent, including possibly a legal secretary, paralegal, insurance representative, or learning whether the county has a public administrator available to fill the role.

Who is the proper plaintiff for a civil lawsuit?

For a deceased plaintiff, the question involves not only when the plaintiff dies, but what caused the death, and what type of claims exist. For example, if the plaintiff dies because of the tortious activity, not only is a new party needed to be substituted in place of the plaintiff (such as a personal representative on behalf of an estate), but the plaintiff’s heirs are also all now plaintiffs under the wrongful death statute.[6] However, personal injury or property damage claims survive death[7], and can be brought by the decedent’s heirs directly if there is no personal representative.[8] Thus an attorney must know who the proper party is to substitute as a representative for the deceased person, and when new classes of plaintiffs are created. These factors also affect who the real party in interest is, who needs to sign settlement agreements, who can execute on judgments, and who can be served.

As stated previously, under Idaho’s wrongful death statute, the heirs are permitted to bring their own claims for the wrongful death of the decedent.[9] These heirs include anyone entitled to succeed the decedent under Idaho’s probate code[10] as well as any spouse, children, stepchildren, and parents.[11] Other family members who rely on the decedent for support may also be heirs.[12]

The statute is unclear as to who should bring the claim, as it says the decedent’s “heirs or personal representatives on their behalf may maintain an action for damages against the person causing the death.”[13] This language seems to give standing to the heirs or the decedent’s personal representatives to bring a claim. However, Idaho law does not appear to indicate that the estate itself has a wrongful death claim, instead the estate may act on behalf of the heirs.[14]

This can cause confusion if the heirs have not agreed to act together and allow the estate to bring such claim, as nothing in the statute or case law discussing the statute bars an heir from bringing a claim independently even if the personal representative has already brought a claim. Thus, it is very possible for a personal representative to bring a wrongful death claim on behalf of heirs who did not agree for the personal representative to act on their behalf, and which claim does not specifically bar the heirs from bringing their own claims. This may mean that unless all the heirs are involved in the lawsuit (whether as original parties or impleaded as parties), there is potential that other plaintiffs could bring identical claims in separate lawsuits.[15]

How to substitute parties

If a party passes away during the pendency of a lawsuit, or if the complaint names a deceased person, then substitution of parties is likely to be necessary. I.R.C.P. 25 deals with this, stating, “If a party dies and the claim is not extinguished, the court may order substitution of the proper party. A motion for substitution may be made by any party or by the decedent’s successor or representative party. If the motion is not made within a reasonable time, the action by or against the decedent may be dismissed.”[16] This substitution usually requires providing to the court an explanation as to who has been appointed as the personal representative or special administrator.

If no steps have been taken to appoint a personal representative, then this is likely an appropriate time to appoint a special administrator. A personal representative is usually appointed in connection with a probate action, which usually requires opening a separate action. However, nothing in the special administrator statute requires opening a probate action for appointment, and therefore, it can be done in the civil action without additional court costs.

At the point where substitution is appropriate, a special administrator may be requested. This typically requires a separate motion and declarations (explaining why a special administrator is preferrable to a personal representative)[17], along with proposed letters of special administration[18] limiting the powers of the special administrator to dealing solely with the lawsuit.

What is a wrongful death claim?

It has long been established that a spouse can bring a loss of consortium claim for injury to a spouse.[19] Loss of consortium claims are dependent on the underlying claim.[20] Therefore, if the injured party died, at common law, the spouse (or possibly the child) had no claim for recovery.[21]

As a result, states have enacted wrongful death statutes to allow heirs to recover for claims that were not allowed under the common law. “These wrongful death statutes are either (1) survival statutes, which preserve the deceased’s cause of action for the heirs while amplifying the amount of damages because of the death; or (2) ‘death acts’ based on Lord Campbell’s Act which creates a new cause of action for the death in the deceased’s heirs. Idaho Code § 5–311 is of the latter type.”[22]

Idaho’s wrongful death statute allows heirs to recover, “such damages may be given as under all the circumstances of the case as may be just.”[23] These damages are typically very broad (allowing both special and general damages),[24] but are not unlimited. While a wrongful death heir may obtain damages for, “the loss of protection, comfort, society and companionship,” of the decedent, they may not recover, “grief and anguish.”[25]

Damages and claims that abate on death of the client

As outlined above, personal injury and property damage claims survive death, but only in a limited fashion. Under Idaho Code § 5-327(1), punitive and exemplary damages are barred when sought against a decedent (i.e. the dead defendant). Under Idaho Code § 5-327(2), a deceased plaintiff’s personal injury and property damage claims survive death, but the estate/heirs may only seek damages for, “(i) medical expenses actually incurred, (ii) other out-of-pocket expenses actually incurred, and (iii) loss of earnings actually suffered, prior to the death of such injured person and as a result of the wrongful act or negligence.” The Idaho Supreme Court has similarly stated, “[A]n action for pain and suffering does not survive the death of the injured.”[26]

What are the applicable time limits?

The first place to start with time limits are the applicable statutes of limitations: two years for wrongful death or personal injury,[27] three years for injury to personal property,[28] four years for oral contract,[29] five years for written contract.[30] These deadlines are often extended in wrongful death claims as there are often minor heirs. Under Idaho Code § 5-230, every statute of limitations (other than for recovery of real property) is extended up to six years.[31] This may mean that a statute of limitations for an adult has run, but continues to run substantially longer for any person who was a minor at the time the claim accrued.

In addition to Idaho Code § 5-230, which extends the time to bring a claim for a minor, all claims against a decedent are extended. Idaho’s probate code states, “The running of a statute of limitations measured from an event other than death or the giving of notice to creditors is suspended during the four (4) months following the decedent’s death but resumes thereafter as to claims not barred pursuant to the sections which follow.”[32]

As the Idaho Supreme Court has noted, this statute provides, “a four-month tolling of the applicable statute of limitations following a decedent’s death.”[33] Thus, based on the plain language, the applicable statute of limitations is tolled if the ostensible defendant dies during the running of the statute of limitations. Similarly, statutes of limitations of claims belonging to decedents are potentially extended by 4 months as well.[34]

Who needs to sign the settlement agreement?

When settling claims, it is important to have all the necessary participants agree. If the defendant has passed away, then likely the proper party to the settlement (if a signature from the defendant is required) is the personal representative or special administrator. Outside of wrongful death claims, the same is likely true for a decedent plaintiff.

In a wrongful death claim, it is important to have all parties in interest sign the releases. This means that the personal representative of the estate and all heirs must sign the agreement in order for all claims to be resolved. Where there are minors involved, this will likely require court approval of the agreements as required by statute.[35] This may take significant negotiation to reach a result that all heirs are willing to accept, particularly if the heirs do not agree on how to distribute the settlement proceeds. If the settlement proceeds are insurance funds, then this problem can potentially be resolved by interpleading the insurance funds.[36]

If however, there is excess exposure, or the heirs/representatives cannot agree on a settlement amount, then it may be impossible to settle with some or any of the heirs until the statute of limitations has run. Stated another way, settling with some heirs does not mean that the remaining heirs are barred from bringing independent claims under the wrongful death statute.

Things to remember

Dealing with deceased clients requires an attorney to remember numerous moving parts. Some examples include:

1. If you have an elderly client with a personal injury claim, it is best to bring the claim sooner, rather than later, so as to avoid having pain and suffering claims abate upon the client’s death.

2. If an estate brings a wrongful death claim on behalf of a decedent, the defending attorney should make sure the estate has permission of the heirs to avoid arguments that the heirs retained their independent claims.

3. In defending a deceased client, it is best to get a personal representative or special administrator appointed as soon as possible to avoid a situation where you have to try to unwind a plaintiff being appointed to represent the defendant’s estate.

These examples show what can go wrong if you are unfamiliar with representing a deceased client in a civil lawsuit. Though this article cannot address every issue, litigation attorneys should make sure to know what potential consequences occur when a client is deceased before or dies during a civil action.

Stephen Adams is Senior Counsel at Gjording Fouser, PLLC in Boise, Idaho. He has represented private, corporate, and governmental entities for the past 15 years, including numerous state and federal appeals. He is the chair of the Idaho State Bar Appellate Practice Section. When he is not hiding in his office writing as many motions as fast as he can, he can be found cooking, composing, reading, or bouncing on the trampoline with his family.

Endnotes

[1] This of course depends on the circumstances, as there may be a need for guardians, conservators, etc.

[2] Idaho Code § 15-3-703(c) (“Except as to proceedings which do not survive the death of the decedent, a personal representative of a decedent domiciled in this state at his death has the same standing to sue and be sued in the courts of this state and the courts of any other jurisdiction as his decedent had immediately prior to death.”)

[3] Idaho Code § 15-3-617.

[4] Idaho Code § 15-3-615.

[5] Idaho Code § 15-3-203(a)(3).

[6] Idaho Code § 5-311

[7] Idaho Code § 5-327(2). These claims are limited in what can be brought.

[8] Idaho Code § 5-327(2).

[9] Idaho Code § 5-311.

[10] Idaho Code § 15-1-201(22). This definition would include those entitled to recover as identified in Chapter 2, Title 15 of the Idaho Code dealing with intestate succession.

[11] Idaho Code § 5-311(2).

[12] Idaho Code § 5-311(2).

[13] Idaho Code § 5-311(1).

[14] Farm Bureau Mut. Ins. Co. of Idaho v. Eisenman, 153 Idaho 549, 553, 286 P.3d 185, 189 (2012) (“Any damages an estate recovers in an action for the wrongful death of the decedent inure solely to the benefit of the heirs.”); Hagy v. State, 137 Idaho 618, 623, 51 P.3d 432, 437 (Ct. App. 2002) (“However, we construe I.C. § 5–311(1) to use ‘personal representative’ to mean the personal representative of the decedent, not of the heirs.”); Hayward v. Valley Vista Care Corp., 136 Idaho 342, 353, 33 P.3d 816, 827 (2001) (“The personal representative can bring an action for wrongful death, and need not join the heirs as parties. ‘[A] personal representative … may sue in this capacity without joining the party for whose benefit the action is brought.’ IDAHO R. CIV. P. 17(a).”).

[15] Dreyer v. Idaho Dep’t of Health & Welfare, 455 F. Supp. 3d 938, 955 (D. Idaho 2020) (“[I]t is clear that two person/s can bring a claim for wrongful death under Idaho Code Section 5-311: (1) the decedent’s heir/s, or (2) the decedent’s personal representative on behalf of the heirs.”).

[16] I.R.C.P. 25(a)(1).

[17] See Idaho Code § 15-3-614(b).

[18] See Idaho Code §§ 15-3-602 and 15-3-702.

[19] Conner v. Hodges, 157 Idaho 19, 27, 333 P.3d 130, 138 (2014). This case also suggests that a loss of consortium type claim may exist arising out of injury to the parent-child relationship as well.

[20] Zaleha v. Rosholt, Robertson & Tucker, Chtd., 131 Idaho 254, 256, 953 P.2d 1363, 1365 (1998).

[21] Castorena v. Gen. Elec., 149 Idaho 609, 614, 238 P.3d 209, 214 (2010).

[22] Castorena v. Gen. Elec., 149 Idaho 609, 614–15, 238 P.3d 209, 214–15 (2010).

[23] Idaho Code § 5-311(1).

[24] Horner v. Sani-Top, Inc., 143 Idaho 230, 237, 141 P.3d 1099, 1106 (2006).

[25] Hayward v. Yost, 72 Idaho 415, 427, 242 P.2d 971, 978 (1952). See also Hepp v. Ader, 64 Idaho 240, 130 P.2d 859, 862 (1942) (“Although the decisions are agreed that recovery may not be had for grief and anguish suffered by the surviving relatives of the deceased, it may be had, in Idaho, for loss of society, companionship, comfort, protection, guidance, advice, intellectual training, etc.”).

[26] Evans v. Twin Falls Cty., 118 Idaho 210, 216, 796 P.2d 87, 93 (1990) (quoting Vulk v. Haley, 112 Idaho 855, 859, 736 P.2d 1309, 1313 (1987)).

[27] Idaho Code § 5-219(4).

[28] Idaho Code § 5-218.

[29] Idaho Code § 5-217.

[30] Idaho Code § 5-216.

[31] Gomersall v. St. Luke’s Reg’l Med. Ctr., Ltd., 168 Idaho 308, 483 P.3d 365, 371 (2021).

[32] Idaho Code 15-3-802(b).

[33] Trimble v. Engelking, 134 Idaho 195, 197, 998 P.2d 502, 504 (2000).

[34] Idaho Code § 15-3-109.

[35] Idaho Code § 15-5-409a.

[36] I.R.C.P. 22; Idaho Code § 5-321.

RON, RON, RON Away: The New Frontier of Notarization

Hillary S. Vauhn

Published October 2021

Real estate law is often the last bastion of resistance to technology. Enter 2020—the year we could do virtually nothing but almost anything virtually—and the real estate industry finally heaved a heavy sigh and succumbed to the pressures of the digital age.

Anyone involved in transactional work is likely familiar with some form of electronic signings, whether exchanging copies of wet-signed documents by fax or e-mail or using cloud-based signing platforms to provide a digital signature. In Idaho, most types of electronically signed or transmitted documents have been legally enforceable since the adoption of the Uniform Electronic Transactions Act (“UETA”) in 2000.[1]

Many real estate transactions have included electronically executed documents for portions of the transaction. However, documents affecting title, conveying an interest in property, and security instruments for real estate financing transactions have long been the holdouts since these documents required an original “wet” signature and notary certificate in order to be recorded in the county records.

Why does it matter if some documents require original signatures and notary acknowledgements? The most obvious answer is time; it takes more time on the part of the person signing, the notary, and often for delivery of the document than electronically executed documents, and all that time needs to be built into a transaction. The tricky dance with traveling signatories (especially when traveling internationally) has always been problematic. But COVID-19 presented a new challenge: the added risk of being in close physical proximity with people you don’t know, exchanging objects that everyone is touching in the middle of a raging, viral pandemic. Virtual transactions became a real-life necessity.

How Did We Get Here?

Quite a few things changed in a relatively short time frame, and all prior to the pandemic. In 2016, the Idaho Secretary of State sought to increase security measures for notary stamps and certificates and bring Idaho’s notary laws up to date with standardized notary laws being adopted across the nation. The Secretary of State introduced, and the Idaho Legislature ultimately adopted, the Revised Uniform Law on Notarial Acts (“RULONA”), which took effect July 1, 2017.[2]

The original version of RULONA adopted in Idaho included provision for electronic notarization, or “e-notary.”[3] The process for electronic notarization is the same as traditional notarization in that the signer still executes the document in front of the notary as a witness; the only difference is that the signer signs and the notary completes the certificate and stamp by electronic means instead of manually with ink. This process is slightly more streamlined, but still requires the signer to “sign” in the presence of the notary. While e-notary certainly made some routine attestations more convenient, its impact on transactions was still limited because of the requirement of personal appearance.

“Any notary that would like to use RON must obtain approval from the Idaho Secretary of State for any platform (or platforms) that the notary will use for RON communications.”

Enter RON.[4] While Idaho was in the process of vetting and passing RULONA, some states were getting truly scandalous and experimenting with technology that obviated the need for the signer to physically appear and sign in front of the notary. The term “remote online notarization” (“RON”) refers to a notarial act where the signer and the notary are physically remote from each other and the parties use simultaneous audio-visual communications technology that allows the signer to “appear” in front of the notary when executing the document. This process includes the use of e-notary because the parties execute and notarize the document using an electronic signature and stamp but goes one step further by modifying the requirement that the signatory be physically present before the notary when signing.

The first iterations of RON legislation were scattershot and only adopted in a few states with wildly different requirements and results. In response, the Mortgage Bankers Association (“MBA”) and the American Land Title Association (“ALTA”) teamed up to develop the MBA-ALTA Model Legislation for Remote Online Notarization, promulgated in 2018, with the intent of standardizing the process and legal framework nationwide.[5] Shortly thereafter, the Uniform Laws Commission issued an amendment to RULONA that included RON provisions that were substantively similar to the MBA-ALTA Model Legislation but worked within the existing RULONA terminology and framework that had already been adopted in a number of states, including Idaho.

Separate from these initiatives, but at the same time that many of these changes were being considered in Idaho, industry groups were pushing for widespread adoption of e-recording by county recorders throughout Idaho.[6] E-recording allows for use of an electronic platform to record documents directly with the county recorder from a remote location instead of physically delivering the original documents to the recorder’s or clerk’s office. This technology drastically reduced transaction times by cutting out deliveries to the county. However, because the party submitting the instrument for recording still had to have to have a wet-signed original in-hand under the existing notary requirements, the process still wasn’t as efficient as it could be.

It was somewhat serendipitous that the standardization and acceptance of the model RON bills intersected with the campaign to expand the availability of e-recording statewide. These innovations are really two sides of the same coin—one allows for electronic creation of an instrument and the other allows the instrument be memorialized in the official records by electronic submission, but both are intended to modernize and streamline these processes for the convenience of the consumer.

By the time Idaho adopted the 2018 RULONA amendment incorporating the RON provisions,[7] every county in Idaho accepted documents for recording through an electronic platform. That makes Idaho one of only a handful of states where documents can be executed, notarized, and recorded electronically in every county in the state.

How Does RON Work?

It’s a little more involved than your average Zoom happy hour, and for good reason. First, any notary using RON communications will still need to satisfy all of the requirements of RULONA except for the physical presence of the signer, which means that the notary must still verify the identity of the signer, confirm the document being signed, witness the electronic signature, and add the notary’s electronic seal. Second, since the notary process requires some exchange of non-public personal information and the parties are communicating via audio-video platform, a few additional precautions are necessary to safeguard information and prevent fraud.

There are now a number of different vendors providing platforms specifically for, or that have been expanded to facilitate, RON services. Any notary that would like to use RON must obtain approval from the Idaho Secretary of State for any platform (or platforms) that the notary will use for RON communications.[8]

When using RON communication, a notary can validate the identity of the signer using any of four methods: (1) the notary’s personal knowledge of and familiarity with the signer;[10] (2) analysis of a credential (e.g. driver’s license or other form of identification) that is verified for the notary by a third-party software process (a “credential analysis”);[11] (3) verification of the signer’s identity using multi-factor authentication (e.g. lots of questions) using information from a variety of private and public databases (“knowledge-based authentication” or “KBA”);[12] or (4) the oath of a witness identifying the signer, so long as the witness’s identity can be verified by one of the above methods.[13]

RON Communication Platform Criteria

Each vendor’s user interface varies, but any communication technology used in Idaho must meet the following criteria[9]:

- The parties must be able to communicate simultaneously through sight and sound.

- The session must be recorded and the notary must communicate this fact to the signer before performing the notarial act. The recording must be retained by the notary for ten years after it was made.

- The platform must include a process or service by which the notary can verify the identity of the signer (discussed more fully below).

- The signer executes the document electronically by drawing, typing a symbol or initials, or affixing a pre-selected signature to the document. The notary must reasonably be able to determine that the document signed is the same instrument being notarized (e.g. by screen sharing an uploaded document). Once that is confirmed, the notary affixes the notarial certificate with a note indicating that the act involved the use of communication technology, and seals with an electronic stamp.

- The resulting document must be tamper-evident (meaning that it must be protected and identify whether anyone has tried to modify or alter the document after it was signed and notarized) and evidenced by a digital certificate.

In practice, a notarization conducted via RON communications generally proceeds as follows: the notary uploads the document or document to be signed into the notary’s selected RON platform, the notary sends a link to the signer to join a recorded session through the communications platform, the signer then either completes the KBA verification or credential analysis (if the notary is not otherwise familiar with the signer), the notary session is then conducted as it would be in-person, the signer digitally executes the pre-loaded document, the notary completes and digitally stamps the notarial certificate, and the software produces a fully-executed and notarized electronic instrument with a tamper-evident certificate.

The document produced can then either be submitted electronically through an e-recording platform or may be printed and physically submitted, so long as the notarial officer certifies that the tangible copy is an accurate copy of the electronic record[14] (the latter procedure is often called “papering out” of the electronic format).

Where Are We Now?

Idaho found itself in the catbird seat with respect to RON when COVID-19 forced business closures and social distancing measures because it had already adopted RON standards and e-recording was available statewide. However, many other states were scrambling to figure out how to keep transactions requiring notarized documents on track. Fewer than ten states had previously adopted and implemented RON standards or were considering them, and it takes a significant amount of lead time to pass legislation and promulgate agency rules. This chaos led, inevitably, to a patchwork quilt of measures including executive orders, use of emergency authorizations, and special legislative sessions, to create a short-term “fix” to satisfy the in-person presence requirement for notarizations.

Thankfully, most of the states that relied on temporary orders or authorizations have now replaced them with more fulsome, permanent legislation that, for the most part, followed one of the two model acts.[15] On the federal level, the bipartisan Securing and Enabling Commerce Using Remote and Electronic (“SECURE”) Notarization Act was introduced initially in 2020, went nowhere, and was reintroduced in 2021 in both the House and the Senate; both bills currently sit in committees.[16] The SECURE Act would permit use of RON nationwide with minimum standards and expressly provide for interstate recognition of instruments notarized using RON.

Some thorny issues remain. The topic du jour is “remote ink notary” or “RIN”, where the signer and the notary both appear on an audio-visual platform and the notary identifies the signer as required by law, but the signer signs the paper document in pen and ink and then transmits the signed document by fax, e-mail, or mail to the notary to complete the notarial certificate and seal. RIN became one of the COVID-19 workarounds in states that did not have an existing framework for the RULONA amendment providing for RON or the MBA-ALTA Model Legislation, or widespread availability of e-recording, because it produced an ink-signed original.

Idaho does not currently allow this practice; RON requirements provide only for a fully electronic execution (even if papering out later). One concern raised surrounds the lack of document control attendant with RIN, i.e. whether the notary can verify that the document the notary receives for stamping is the same instrument the notary witnessed being signed.

State RON laws still vary as to methodology, acceptable communication platforms, identity-proofing requirements, and where the signer may be located.[17] Given these discrepancies, many title insurance underwriters and lenders also have varying policies with respect to acceptance of instruments notarized through RON technologies. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac issued new guidance in 2020 largely accepting but outlining the agencies’ requirements for documents notarized through RON.[18] If history is any guide, it will likely take some time and increased certainty and uniformity in legal standards for these industries to fully embrace this new technology.