Category: Digital Advocate

Commissioner’s Column: Well Being in Law

By Jillian H. Caires

As lawyers, we have a tough job. We work long hours and feel a hefty pressure to obtain the best possible outcomes for our clients. Attorneys meet clients and victims in their hour of greatest need and walk alongside them as they navigate crisis. Our judges see some of the darkest parts of humanity daily. We can all likely empathize with the stress of law school and studying for the bar exam. Additionally, as Idaho lawyers, we go through long, dark winters, which, in my opinion, multiplies the weight we feel as lawyers (thank goodness it is FINALLY spring!).

Most of us have experienced stress from our work – in my career, I have experienced physical manifestations of stress such as a chronically sore shoulder and I have gone through periods of burn out. We have also likely all known colleagues in the legal profession who have self-medicated with alcohol or drugs or been diagnosed with anxiety or depression. One of my law school classmates tragically took his own life several years ago, a shock to those who knew him as an upbeat friend who would lift others up. Sadly, many of us have been touched by this type of tragedy.

The first full week of May is Well-Being Week in Law[1], and May is Mental Health Awareness Month; a month focused on building awareness about, and breaking stigmas around, mental health.[2] “Mental health includes our emotional, psychological, and social well-being. It affects how we think, feel, and act. It also helps determine how we handle stress, relate to others, and make choices.”[3] In a profession where we often tend to the needs of others before our own and in a state with a suicide rate higher than the national average, it is critical that we take time as individuals and as a profession to build our mental health awareness.[4] Maintaining well-being is part of lawyers’ ethical duty of competence.

We are instructed by airline attendants that in case of emergency, we must secure our own oxygen mask first before we help others. The same is true when it comes to taking care of our own mental health and well-being: we must take care of ourselves first if we are to successfully help others. Part of taking care of ourselves is knowing what warning signs to watch for. Some warning signs of mental health problems include: withdrawing from people or activities; eating or sleeping too much or too little; experiencing a drop in energy levels; feeling hopeless; increasing use of substances; and thinking of harming one’s self or others.[5]

As a Board of Commissioners, we took time last fall to develop our strategic vision for the Idaho State Bar. One focus of that strategic vision is supporting the well-being of our members. If you have a passion for well-being, please keep your eyes open for an opportunity to join the Bar’s Well-Being Committee which will soon be formed by the Commission.

Jillian H. Caires is an Idaho native and a proud Washington State University Cougar and Gonzaga Bulldog. After clerking for the Honorable Benjamin Simpson, Jillian spent several years in private practice in Coeur d’Alene before joining the in-house legal team of Avista Corporation. In her free time, Jillian enjoys baking, gardening, walking her standard poodle, and spending time with her family.

[1] https://lawyerwellbeing.net/lawyer-well-being-week/.

[2] https://www.samhsa.gov/programs/mental-health-awareness-month.

[3] https://www.mentalhealth.gov/basics/what-is-mental-health.

[4] https://www.kff.org/statedata/mental-health-and-substance-use-state-fact-sheets/idaho/.

[5] https://www.mentalhealth.gov/basics/what-is-mental-health.

Admissions Department Report

By Maureen Ryan Braley

The Idaho State Bar Admissions Department administers the rules governing admission to the practice of law in Idaho. Attorneys can be admitted by taking the Idaho Bar Exam, transferring a Uniform Bar Examination (“UBE”) score to Idaho, or through reciprocal admission (admission based on practice experience in another state). The Admissions Department also oversees limited admission to the practice of law in Idaho through a House Counsel license (working in-house for an Idaho employer), Emeritus Attorney license (limited license to do pro bono work), Military Spouse Provisional admission (servicemember spouse is stationed in Idaho), pro hac vice admission, and Legal Intern licenses.

Idaho Bar Exam Statistics

A record number of people took the Idaho Bar Exam in 2022. 93 people took the exam in February 2022 and 182 people took the exam in July 2022. The overall pass rate for the 2022 bar exams was 59.6%, which is down over five percentage points from the 2021 overall pass rate of 64.7%. The increase in bar exam applicants was due to the increased enrollment at Concordia University School of Law before its closure in the spring of 2020. Most of the Concordia students transferred to the University of Idaho College of Law and graduated in May 2022. Therefore, we will likely see a decline in the number of people taking the Idaho Bar Exam in 2023.

Reciprocal and UBE Admission Trends

As we know, Idaho’s population grew during the pandemic. We saw higher numbers of reciprocal applicants in 2020 and 2021, with 94 attorneys applying in 2020, followed by a record high 109 attorneys in 2021. Reciprocal applicant numbers returned to pre-pandemic levels in 2022, when 81 attorneys applied for reciprocal admission. Idaho has reciprocity with 35 jurisdictions. UBE applicant numbers have held steady at 50 per year since 2020.

NextGen Bar Exam

In 2018, the National Conference of Bar Examiners (“NCBE”), the entity that develops the UBE, created the Testing Task Force to determine the knowledge and skills entry-level lawyers should be expected to know and how that knowledge and those skills should be assessed on the bar exam. After several years of research, the Testing Task Force recommended that the NCBE develop what it refers to as the “NextGen Bar Exam.” The NCBE is currently conducting pilot and field testing and developing content scope outlines for the NextGen Bar Exam. The NCBE will finalize this work in early 2026, with the NextGen Bar Exam ready to be deployed for the July 2026 bar exam.

In February 2023, the Board of Commissioners of the Idaho State Bar created a NextGen Bar Exam Task Force to monitor developments with the NextGen Bar Exam and consider whether it should be implemented in Idaho.

Spotlight on Belinda Brown, Idaho State Bar Admissions Analyst

A law student’s or lawyer’s first contact with the Idaho State Bar occurs during the admissions process. And since 2009, that first contact has been with Belinda Brown, the Idaho State Bar Admissions Analyst. Belinda handles the intake on all applications for admission. She communicates with dozens of lawyers daily, answering questions about the admissions process and updating them about the statuses of their applications. She is patient, courteous and professional. I have learned a lot from her and am privileged to work with her.

Maureen Ryan Braley is the Associate Director of the Idaho State Bar and the Idaho Law Foundation. Her job duties include overseeing bar admissions in Idaho. She clerked for Chief Justice Gerald F. Schroeder of the Idaho Supreme Court and practiced law for six years in Boise before joining the Idaho State Bar staff in 2011. Maureen is a “double Zag” having earned an undergraduate degree in history and a law degree from Gonzaga University.

Law Related Education Wraps Up 2023 Idaho High School Mock Trial Competition

By Carey A. Shoufler

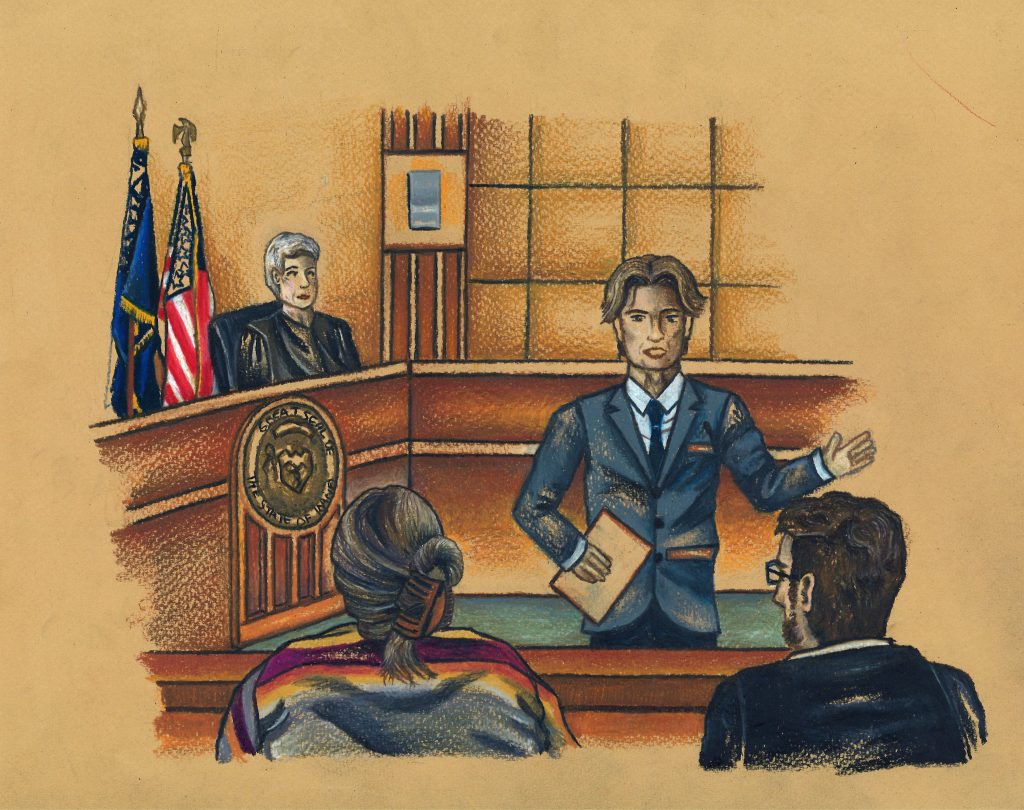

Title Page Image Caption: 2023 Idaho Mock Trial Champions, The Ambrose School, Meridian.

The Idaho Law Foundation’s Law Related Education Program hosted its annual High School Mock Trial State Championship from Wednesday to Friday, March 15 to 17. For the first time since 2019, the three-day tournament was held in-person. This year, students explored a criminal case that centered on a charge of theft by possession of stolen property charged against a college student who had started a business refurbishing computers for other students.

For 2023, 216 high school students from 24 teams registered to participate in the mock trial competition. One hundred thirty-eight teachers, judges, attorneys, and other community leaders donated their time to serve as coaches, advisors, judges, and competition staff.

Twelve teams advanced from regional competitions held in Lewiston and Boise. These teams participated in four rounds of competition on Wednesday and Thursday at the Ada County Courthouse with the top two teams facing off for the state championship at the Idaho Supreme Court on Friday morning. The following schools participated in Idaho’s state tournament:

- The Ambrose School (Meridian, two teams)

- Boise High School (two teams)

- Lewiston High School

- The Logos School (Moscow, two teams)

- Mountain Home High School

- Thunder Ridge High School (Idaho Falls)

- Timberline High School (Boise)

- Victory Charter School (Nampa, two teams)

The following teams placed in the top four for Idaho’s state tournament:

2023 State Champion: The Ambrose School (A Team)

State Runner Up: Logos School (A Team)

Third Place: Mountain Home High School

Fourth Place: Victory Charter School (A Team)

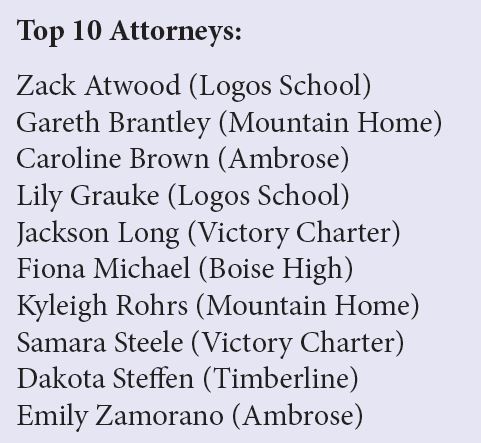

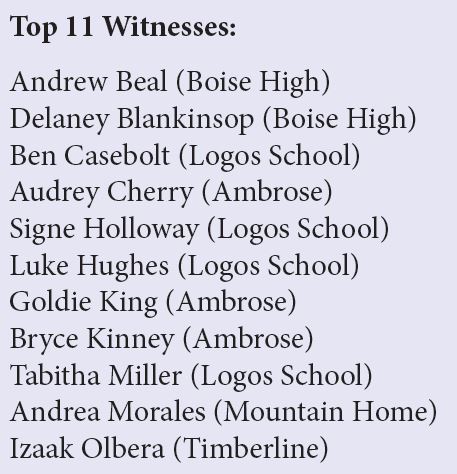

Mock trial team members who played roles as attorneys and witnesses had the opportunity to be recognized for individual awards. For each trial through four rounds of competition, each judge had the opportunity to select the students they believed gave the best performances for the trial. The top witnesses and attorneys for the 2023 competition include:

As part of the state competition, Idaho’s Mock Trial Program, in partnership with the Professionalism & Ethics Section, developed the Civility & Ethics Award, created to highlight the importance of civility and professionalism among teams participating in mock trial. During the state competitions teams observe and interact with each other and submit their nomination for the award. For 2023, Logos School B Team was chosen by the other teams as the recipient of this year’s award.

Idaho’s mock trial program also hosts a Courtroom Artist Contest as part of the program. Artists observed trials and submitted sketches that depict courtroom scenes. The top three entries for 2023 were:

First Place: Taelyn Baiza (Boise High School)

Second Place: Nam Bui (Lewiston High School)

Third Place: Shalyce Graham (Victory Charter School)

The Ambrose School will represent Idaho at the National High School Mock Trial Championship in May in Little Rock, Arkansas and Taelyn Baiza will represent Idaho in the National Courtroom Artist Contest.

The Idaho Law Foundation’s Law Related Education Program would like to thank the sponsors and volunteers who helped during the 2023 mock trial season. We couldn’t do our important work without your support.

Plans will soon begin for the 2024 mock trial season. For more information about how to get involved with the mock trial program, visit idahomocktrial.org, or contact Carey Shoufler, Idaho Law Foundation Law Related Education Director, at cshoufler@isb.idaho.gov.

For 30 years, Carey A. Shoufler has worked in education and communications in an array of settings. In her current role, Carey has spent the last 17 years working as the Law Related Education Director for the Idaho Law Foundation. Carey utilizes her experience as an educator to provide leadership and management for a statewide civic education program. She obtained her bachelor’s degree in English literature from Mills College in Oakland, California and her master’s degree in instructional design from Boise State University. A native Idahoan, Carey returned to Boise in 1999 after working for 13 years as a teacher and educational administrator in Boston. When not working, Carey likes to walk her dogs, knit, read, bake pies, and spend time with her grandchildren.

ABA Midyear Report

By R. Jonathan Shirts

For the first time since February 2020, the ABA’s Midyear Meeting was held in-person from February 1-6, 2023. We were warmly welcomed by the city of New Orleans; and I do mean warmly – temperatures were in the mid-50’s to mid-60’s while we were there, much warmer than anywhere in our great state during that time. Before this, I had not had the opportunity to visit New Orleans, and it gave me some unique experiences – I’m pretty sure I have never heard an accordion solo in a street band before.

One thing I have always wanted to experience was Mardi Gras in New Orleans; I still haven’t, but I feel like I’ve come close because the city was ramping up for it a month early. I heard someone say that New Orleans looks for any excuse to have a parade or a party, and it lived up to that billing – the entire House of Delegates was given a Second Line parade from the hotel to the Louisiana Supreme Court on Friday night, and the city hosted a pre-Mardi Gras parade Saturday night.

Once the House of Delegates recovered from the celebratory welcome to New Orleans, the real business began. This was the last House of Delegates meeting for the long-time ABA Executive Director, Jack Rives, and his address to the House discussed many of the advancements the ABA has been able to make during his tenure. [i] A new President-Elect, William R. Bay of Missouri, was selected to take up the gavel as President of the ABA in August 2024.[ii] He stated that one of his goals is to make all members of the legal profession feel welcome in the ABA, regardless of political, ideological, or other beliefs.[iii]

There were a number of Resolutions up for debate that were very hot topics of discussion leading up to the actual House of Delegates meeting.[iv] One of the major discussions surrounded a Resolution from the ABA’s Council of the Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar. In November 2022, the Council voted to approve a change for ABA-accredited law schools which would eliminate the requirement for applicants to law schools to have taken the LSAT or another similar admissions test.[v] Both sides of the debate talked about how they felt that either keeping or eliminating the admissions test would enhance diversity within the legal profession. Being a fairly recent law school graduate, I personally struggled with understanding how the elimination of a relatively-objective measure in the admissions process would enhance diversity in the profession. But I also understood the arguments that marginalized groups and people of color have historically scored much lower on average on the LSAT and other admissions tests.[vi]

What we didn’t have available until the very last minute, however, was any objective data describing how elimination of an admissions test would promote or stifle diversity in law school classes. The data we were given the morning of the vote described how elimination of an admissions test did not foster a more diverse group of applicants, but in some situations, actually reduced it.[vii] In the end, the House of Delegates voted to send this Resolution back to the Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar for more study on this issue, something the House of Delegates is allowed to do twice. After that, the Council can take any action it deems necessary without further input from the House.[viii] After a spirited debate, the House of Delegates voted to send this Resolution back to the Council for further study; however, 11 days later, the Council voted to return the Resolution to the House of Delegates for consideration at its next meeting.[ix]

Another lengthy and spirited debate surrounded the House’s consideration of a Resolution which would make it the ABA’s official policy that the Supreme Court of the United States should adopt a binding code of ethics.[x] After a significant amount of rousing debate, the House voted to pass the Resolution.[xi]

Other resolutions considered and passed involved removal of Confederate monuments and pictures from courthouses,[xii] support for anti-Semitic measures,[xiii] and international wildlife crime enforcement protocols.[xiv] There were also Resolutions passed discussing the rights of women to travel for medical procedures including abortions,[xv] the rights of intersex children to have informed consent before certain surgical procedures,[xvi] and 10 principles that would improve gender parity among criminal attorneys.[xvii]

The next ABA Meeting from August 2-8 will be much closer to us as it is being hosted in the beautiful city of Denver, Colorado. I would encourage anyone who is interested in voicing your concerns or comments to the House of Delegates to attend that meeting. Not only would it be a great networking opportunity and a great place to get CLE’s on topics relevant to today’s practice of law, it’s a way to make your voice known. If you have any questions about attending the ABA Annual Meeting, the work of the House of Delegates, or the ABA in general, any of your Idaho Delegates would be happy to speak with you.

Until next time, thank you all for being a fantastic Bar that I am proud to represent.

R. Jonathan Shirts graduated from the University of Idaho College of Law in 2018 and is currently the Staff Attorney for the Hon. Randy Grove of the Third District. He has also worked as the Staff Attorney for the Hon. Nancy Baskin and Hon. George Southworth. He enjoys good books and spending time in the outdoors with his wife, daughter, and two sons.

[i] See, https://www.abajournal.com/web/article/jack-rives-touts-cost-cutting-progress-in-final-house-address-as-aba-executive-director.

[ii] See, https://www.abajournal.com/web/article/change-is-good-a-says-aba-president-elect-nominee.

[iii] Id.

[iv] A full list of the Resolutions with executive summaries considered during the 2023 Midyear Meeting can be found at https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/house_of_delegates/summary-of-resolutions/2023-midyear-summary-of-resolutions.pdf (“Resolutions”).

[v] Resolutions, pp. 65-78.

[vi] Id.

[vii] Id.

[viii] See, RULES OF PROCEDURE HOUSE OF DELEGATES, §45.9 Law School Accreditation, https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/house_of_delegates/constitution-and-bylaws/constitution-and-bylaws.pdf.

[ix] See, https://www.abajournal.com/magazine/article/testing-standards-entrance-exams-like-the-lsat-remain-an-accreditation-requirement-after-proposed-change-is-voted-down.

[x] See, Resolution 400, https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/house_of_delegates/2023-midyear-supplemental-materials/400-midyear-2023.pdf.

[xi] See, https://www.abajournal.com/magazine/article/scotus-ethics-code-proposed-a-binding-code-for-justices-is-needed-to-protect-the-courts-credibility-delegates-say.

[xii] See, https://www.abajournal.com/magazine/article/reminder-of-injustice-aba-urges-removal-of-confederate-monuments-from-courthouse-grounds.

[xiii] See, https://www.abajournal.com/web/article/aba-passes-resolution-condemning-antisemitism.

[xiv] See, https://www.abajournal.com/web/article/resolution-508-united-nations-must-adopt-wildlife-crime-protocol-to-stop-illegal-trafficking.

[xv] See, https://www.abajournal.com/web/article/resolution-513-aba-supports-right-to-travel-for-abortion-services-and-other-medical-care.

[xvi] See, https://www.abajournal.com/web/article/house-passes-resolution-involving-consent-for-children-with-intersex-traits.

[xvii] See, https://www.abajournal.com/magazine/article/across-the-divide-aba-endorses-10-principles-to-improve-gender-equality-in-the-criminal-legal-profession.

Idaho’s Cobalt Belt & Seamount Crusts: Emerging Opportunities in the Pursuit of Battery Minerals & Renewable Energy Infrastructure

By Catherine O. Danley

Northwest of Challis, in the Salmon River Mountains, an Australian mining company is opening a new cobalt mine in Idaho.[i] Jervois Global Ltd.’s mine sits along the Idaho Cobalt Belt – a 64 kilometer long stretch of cobalt and copper-bearing deposits in the historic Blackbird Mine area.[ii] It is the largest cobalt resource in the United States and Jervois is the first cobalt mine the U.S. has seen operating on its shores in decades.[iii] In fact, Jervois is one of only two mines in the world where cobalt is the principal product.[iv] The other is in Morocco.[v]

Interest in cobalt mining is rising alongside demand for clean energy infrastructure and consumer electronics, particularly as governments seek ways to secure renewable energy resources and reduce their carbon emissions impact. The rising demand for electric vehicles has been a major catalyst under the Biden administration to push for cobalt specifically. The Salmon River Mountains, however, aren’t the only source of cobalt deposits that are attracting mining interests. Minerals in the seabed have been considered a potential source of mining sites since the 1970s and 1980s when depressed metal prices had companies and countries looking to sea for new deposits. Deep sea technology just wasn’t up to the task to make mining economical, much less truly feasible.[vi]

The search for cobalt, and other minerals crucial to modern technology, may be changing that. This article will briefly discuss the rising demand for cobalt, the minerals of the seabed, and new developments unfolding in deep sea mining, international laws governing seabed resources, and the ongoing balancing act between environmental protections and the need for minerals in green energy markets.

Why Cobalt?

Cobalt is a key ingredient in lithium-ion batteries that powers much of our modern technology, including laptops, cell phones, and electric vehicles.[vii] Using cobalt stabilizes the battery’s chemistry, prevents fires, and allows the battery to hold a longer charge.[viii] Cobalt also allows manufacturers to add other materials – such as nickel – to help battery performance.[ix]

Electric vehicles and other forms of renewable energy technology have been on the rise for years, but recent legislation and modern drives towards green energy have been powerful catalysts to mineral demand.[x]

For example, the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, passed last August, includes tax credit provisions for electric vehicle purchasers.[xi] These tax credits are part of the Biden administration’s goal to hit a 50% electric vehicle target of sales shares in the U.S. by 2030, and to cut U.S. vehicle emissions in half within the same time frame.[xii] It’s an ambitious goal dependent, at least in part, on the manufacturers’ ability to source cobalt and other minerals essential for electric vehicle production.

The Department of Energy also announced $3.16 billion from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act will be used “to make more batteries and components in America, bolster domestic supply chains, create good-paying jobs, and help lower costs for families.”[xiii]

All of this manifests at a time where nations are looking for renewable energy solutions. Transitions to clean energy technology are expected to increase global demand for critical minerals by 400-600%, while battery minerals will increase as much as 4,000%.[xiv] Most of the world’s cobalt supply, however, is controlled abroad, which has raised national security concerns.[xv]

The Congo (Kinshasa) continues to be the leading source of cobalt production, accounting for 70% of the world’s production, while China remains the world’s leading producer of refined cobalt. [xvi] China is the world’s leading consumer as well.[xvii] Other key minerals are controlled overseas too. The U.S. imports most of its rare earth metals, with 74% coming from China, 8% from Malaysia, 5% from Estonia and Japan, and the remainder from a mix of nations.[xviii]

Rare earths serve diverse and highly specialized uses, such as construction of mobile phones, advanced motors, generators, oil-refinery catalysts, and superstrong magnets.[xix] Like cobalt, demand for rare earths is rising too: the estimated value of imported rare-earth compounds increased by 25% from 2021 to 2022 alone, and global mine production is estimated to have increased to 300,000 tons of rare earth oxide equivalent.[xx]

Idaho is beginning a new chapter in its mining history as “the world faces a myriad of challenges in transitioning to clean energy.” [xxi] The ocean floor just may be another source of minerals that “will help meet a massive new demand for electric vehicle (EV) battery metals.”[xxii]

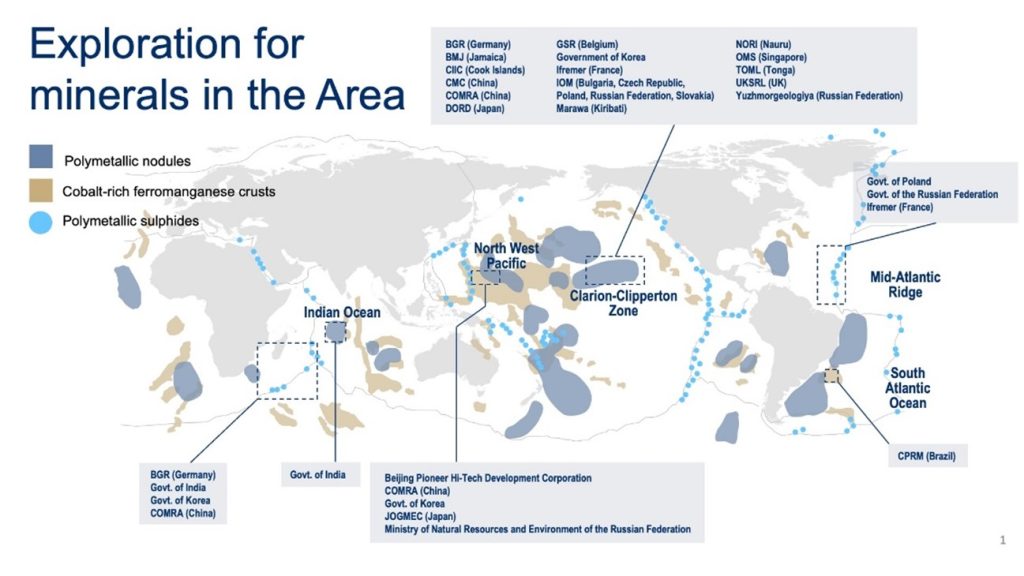

Minerals of the Seabed

According to the U.S. Geological Survey, “[m]ore than 120 million tons of cobalt resources have been identified in polymetallic nodules and crusts on the floor of the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans.”[xxiii] There are two types of mineral deposits mentioned in that data (nodules and crusts), which are located in different regions of the seabed. Polymetallic nodules are what they sound to be: varying sized “rocks” sitting scattered across the sediment of abyssal plains – a cold, dark, and flat expanse of seabed in the central Pacific.[xxiv]

Each nodule tends to contain “at least 27 percent manganese, about 1 percent each of copper and nickel, and 0.2 percent cobalt.”[xxv] Whereas cobalt crusts “grow on hard-rock substrates of volcanic origin by the precipitation of metals dissolved in seawater in areas of seamounts, ridges, [and] plateaus.”[xxvi] These deposits are found in international waters but sometimes fall into areas known as a country’s “Exclusive Economic Zone,” or EEZ. An EEZ is a zone of water that extends 200 nautical miles from a nation’s coast.[xxvii] Importantly, resources within a nation’s EEZ fall within that nation’s jurisdiction.

Just how much money is in seabed minerals? Some reports have estimated deep-sea minerals to be worth $150 trillion, or about “nine pounds of gold for every person on earth.”[xxviii] The trouble is access – technology simply hasn’t advanced yet to a degree that makes mining the deep sea economical.

It’s only been over the last few years that major technological developments have led to the possibility of commercially exploiting seabed minerals. One of the more recent milestones happened just last year. In May of 2022, The Metals Company, Inc. (Canada), and Allseas (a Swiss contractor) successfully completed deep-water tests with the Hidden Gem, “the world’s first fully operational deep-sea mineral production vessel.”[xxix]

Six months later, in November 2022, the Hidden Gem reached another milestone. Engineers drove a pilot collector across 80 kilometers of the Pacific seafloor and collected 4,500 tons of polymetallic nodules through a riser system to the surface production vessel.[xxx] The nodules were transported up 4.3 kilometers (2.6 miles) of riser pipe to the sea surface.[xxxi] The Hidden Gem’s pilot trials are the first integrated nodule collection tests since the 1970s to be conducted in the Clarion Clipperton Zone, a nodule-rich area of the central Pacific Ocean.[xxxii]

Uniform Rules Governing Deep Sea Mining

Deep sea mining doesn’t just require the technology and engineers to reach deep-sea minerals; there are layers of international rules and regulations governing seabed mineral rights. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (“UNCLOS”) governs deep sea mining of the “Area” – “the seabed and ocean floor and subsoil thereof, beyond the limits of national jurisdiction.”[xxxiii] Under UNCLOS, the international seabed and its resources are considered the common heritage of mankind.[xxxiv] This is a legal concept that dates back to ancient times, when the Roman jurist Marcianus wrote that the sea, its fish, and even coastal waters were “communis omnium naturali jure” or “common or open to all men by the operation of natural law.”[xxxv] Because the oceans belonged to everyone, they could be appropriated by no one.[xxxvi]

Today, all Area activities are conducted for the benefit of all humanity. When a state mines the deep seabed it must distribute economic shares to developing nations, encourage and complete marine scientific research, take measures to protect the marine environment, promote the transfer of technology and scientific knowledge among other states, and promote the participation of developing states in activities within the Area.[xxxvii] The International Seabed Authority (“ISA”) is the governing authority charged with implementing each of these requirements, in addition to establishing rules and procedures for mining and mineral rights.[xxxviii]

In short, nations cannot lay direct claims to seabed resources outside of their jurisdiction, i.e. beyond the 200 nautical miles of their EEZ. They must seek mining claims through the ISA’s regulatory framework and the “Mining Code” – comprehensive mining rules, regulations, and procedures that apply to each type of mineral deposit in the seabed: polymetallic nodules, polymetallic sulfide deposits, and cobalt crusts.[xxxix] Coastal states can also seek to demonstrate an outer continental shelf that extends more than 200 nautical miles from its shores (again, an area traditionally beyond its jurisdiction) to obtain sovereign rights for exploration and exploitation of its natural resources.[xl]

To date, the ISA has entered into five exploration contracts for cobalt, including JOGMEC (Japan), COMRA (China), Russia, the Republic of Korea, and CPRM (Brazil).[xli] The ISA has entered into an additional 26 exploration contracts for polymetallic nodules (in the Clarion Clipperton Zone of the central Pacific Ocean) and polymetallic sulphides (deposits that build up beneath hydrothermal vents or “black smokers”).

You might notice that there’s a mix of private companies and foreign nations contracting with the ISA. Since 2010, both national agencies and private companies have been involved in exploration activities and contracting.[xlii] Sometimes international efforts overlap. The Metals Company, for example, is operating through its subsidiaries that hold exploration contracts and commercial rights to three areas within the Pacific’s Clarion Clipperton Zone. [xliii] It’s also sponsored by the governments of Nauru, Kiribati, and the Kingdom of Tonga.[xliv]

Where does the U.S. fall into all this deep-sea mineral exploration? The short answer is, we don’t. The United States has never ratified the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, nor is it a member state of the ISA.[xlv] While the United States remains a consistent and official observer at ISA proceedings, we have yet to establish a legal regime or foundation to participate in seabed mineral extraction. Whether we can participate without being a party to UNCLOS remains to be seen.[xlvi] Where American companies have wanted to participate in deep-sea mining interests, they’ve gone through foreign subsidiaries to gain legal access to the Area.[xlvii]

The Balance

Whether in Idaho or in international waters, mining becomes a balancing act between environmental protections and harvesting crucial minerals. Environmental and social concerns abound. Here are just a few examples to consider:

- In Idaho, the Jervois cobalt mine is close to the Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness and connects by a creek to steelhead and Chinook salmon runs. Concerns of water contamination run high, especially since the Blackbird Mine remains a Superfund site where contaminated runoff entered water bodies during high flows.

- Terrestrial mining has historically demonstrated the potential for incredible environmental destruction. How much worse could the effects be deep in our oceans, which we depend on for resources, food, navigation, trade, and even climate?

- The effects of deep-sea mining are as unknown as the environments we’re diving into. Will the noise and sediment plumes of mining operations disrupt sensitive ecosystems? Will industrial mining alter marine landscapes in ways that affect species, habitat, and nutrient flow?

- Historically, mining has occurred in remote areas near indigenous peoples and minorities. How will they be affected with future mining opportunities?

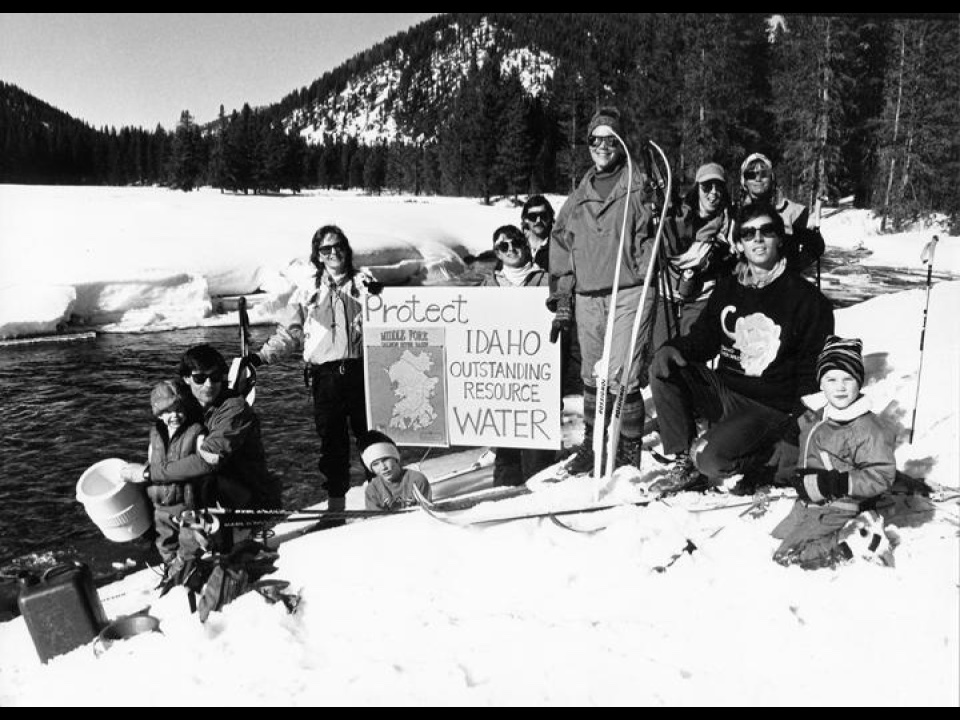

Prudence is undoubtedly needed as mining efforts push forward at sea and on land, and balance between conservation and resource extraction is needed more than ever. Jervois has partnered with the Idaho Conservation League to address some of our more local environmental concerns. For the last three years, Jervois has funded projects that protect and restore fish habitats near the Upper Salmon River and protect crucial salmon species and spawning grounds. It has made $150,000 available each year for such conservation projects and plans to partner with the Idaho Conservation League throughout its 30 to 40 years of mining operations.[xlviii]

Ultimately, transitioning away from a carbon economy means transitioning towards a mineral one.[xlix] Clean energy technologies simply require more minerals. “A typical electric car requires six times the mineral inputs of a conventional car and an onshore wind plant requires nine times more mineral resources than a gas-fired plant.”[l] Since 2010, the average demand for “minerals needed for a new unit of power generation capacity has increased by 50%.”[li] Mining cobalt and similar resources has the potential to help develop our renewable energy infrastructure and spur economic growth. Not to mention supply the key minerals needed in items as common and crucial as batteries. While many questions and issues remain to be solved, just as many opportunities lie ahead.

Catherine O. Danley currently serves as a law clerk to the Honorable Gregory W. Moeller at the Idaho Supreme Court. She received her J.D. from the S.J. Quinney College of Law with a certificate in Environmental and Natural Resources Law. In her free time, Catherine enjoys hiking and kayaking in scenic Idaho.

[i] Ian Max Stevenson and Kevin Fixler, Cobalt Mining excavations return amid electric vehicle push. They’re coming to Idaho, Idaho Statesman (Dec. 27, 2022), https://www.idahostatesman.com/news/northwest/idaho/article266874121.html;

[ii] Idaho Cobalt Belt, Jervois: Idaho Cobalt Operations, https://jervoisidahocobalt.com/idaho-cobalt-operations/idaho-cobalt-belt/ (last visited Feb. 16, 2023).

[iii] Jervois: Idaho Cobalt Operations, https://jervoisidahocobalt.com/ (last visited February 16, 2023); Stevenson and Fixler, supra note 1.

[iv] U.S. Geological Survey, Cobalt: Mineral Commodity Summary (Jan. 2023), https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2023/mcs2023-cobalt.pdf.

[v] Id.

[vi] “Mining for polymetallic nodules is an enormous challenge that has been compared to standing on top of a skyscraper on a windy day and trying to suck marbles off the street with a vacuum cleaner hose.” Jason C. Nelson, The Contemporary Seabed Mining Regime: A Critical Analysis of the Mining Regulations Promulgated by the International Seabed Authority, 16 Colo. J. Int’l Envtl. L. & Pol’y 27, 40 (2005).

[vii] Stevenson and Fixler, supra note 1.

[viii] Id.

[ix] Id.

[x] See The White House, Fact Sheet: Securing a Made in America Supply Chain for Critical Minerals (Feb. 22, 2022), https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/02/22/fact-sheet-securing-a-made-in-america-supply-chain-for-critical-minerals/.

[xi] See generally Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, PL 117-169, August 16, 2022, 136 Stat 1818.

[xii] U.S. Dep’t of Trans., Historic Step: All Fifty States Plus D.C. and Puerto Rico Greenlit to Move EV Charging Networks Forward, Covering 75,000 Miles of Highway (Sept. 27, 2022), https://www.transportation.gov/briefing-room/historic-step-all-fifty-states-plus-dc-and-puerto-rico-greenlit-move-ev-charging.

[xiii] U.S. Dep’t of Energy, Biden Administration Announces $3.16 Billion from Bipartisan Infrastructure Law to Boost Domestic Battery Manufacturing and Supply Chains (May 2, 2022), https://www.energy.gov/articles/biden-administration-announces-316-billion-bipartisan-infrastructure-law-boost-domestic.

[xiv] Securing a Made in America Supply Chain for Critical Minerals, supra note 10.

[xv] Stevenson and Fixler, supra note 1; Keith Bradsher, Amid Tension, China Blocks Vital Exports to Japan, N.Y. Times (Sept. 22, 2010), https://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/23/business/global/23rare.html.

[xvi] U.S.G.S., Cobalt, supra note 4.

[xvii] Id.

[xviii] U.S. Geological Survey, Rare Earths: Mineral Commodity Summary (Jan. 2023), https://pubs.usgs.gov/periodicals/mcs2023/mcs2023-rare-earths.pdf.

[xix] Catherine Danley, Diving to New Depths: How Green Energy Markets Can Push Mining Companies into the Deep Sea, and Why Nations Must Balance Mineral Exploitation with Marine Conservation, 44 Wm. & Mary Envtl. L. & Pol’y Rev. 219, 223 (2019).

[xx] U.S.G.S., Rare Earths, supra note 17.

[xxi] Deep-sea polymetallic nodule collection, Allseas, https://allseas.com/activities/deep-seapolymetallicnodulecollection/ (last visited Feb. 16, 2023).

[xxii] Id.

[xxiii] U.S.G.S., Cobalt, supra note 4.

[xxiv] Danley, supra note 19 at 225.

[xxv] Id.

[xxvi] Minerals: Cobalt-rich Ferromanganese Crusts, Int’l Seabed Auth., https://www.isa.org.jm/exploration-contracts/cobalt-rich-ferromanganese (last visited Feb. 16, 2023).

[xxvii] Id. See also North Sea Continental Shelf Cases (Ger./Neth.; Ger./Den.), Judgment, 1969 I.C.J. 3, ¶ 19 (Feb. 20) (“the rights of the coastal State in respect of the area of continental shelf that constitutes a natural prolongation of its land territory into and under the sea exist ipso facto and ab initio, by virtue of its sovereignty over the land, and as an extension of it in an exercise of sovereign rights for the purpose of exploring the seabed and exploiting its natural resources. In short, there is here an inherent right.”).

[xxviii] Danley, supra note 19 at 219.

[xxix] Hidden Gem, Allseas, https://allseas.com/equipment/hidden-gem/ (last visited Feb. 16, 2023); The Metals Company, The Metals Company and Allseas Announce Successful Deep-Water Test of Polymetallic Nodule Collector Vehicle in the Atlantic Ocean at a Depth of Nearly 2,500 Meters,The Metals Company (May 5, 2022), https://investors.metals.co/news-releases/news-release-details/metals-company-and-allseas-announce-successful-deep-water-test. Videos highlighting the pilot nodule collection and other tests are available to watch on the Allseas website.

[xxx] The Metals Company, NORI and Allseas Lift Over 3,000 Tonnes of Polymetallic Nodules to Surface from Planet’s Largest Deposit of Battery Metals, as Leading Scientists and Marine Experts Continue Gathering Environmental Data,The Metals Company (Nov. 14, 2022), https://investors.metals.co/news-releases/news-release-details/nori-and-allseas-lift-over-3000-tonnes-polymetallic-nodules.

[xxxi] Id.

[xxxii] The Metals Company, TMC and Allseas Achieve Historic Milestone: Nodules Collected from the Seafloor and Lifted to the Production Vessel Using 4 km Riser During Pilot Trials in the Clarion Clipperton Zone for First Time Since the 1970s, The Metals Company (Oct. 12, 2022), https://investors.metals.co/news-releases/news-release-details/tmc-and-allseas-achieve-historic-milestone-nodules-collected.

[xxxiii] United Nation Convention on the Law of the Sea, Preamble, Dec. 10, 1982, 1833 U.N.T.S. 397, 445-77 (hereinafter UNCLOS).

[xxxiv] UNCLOS, Part XI, § 2, art. 136, 137, 140.

[xxxv] Peter Prows, Tough Love: The Dramatic Birth and Looming Demise of UNCLOS Property Law (and What Is to Be Done About It), 42 Tex. Int’l L.J. 241, 249 (2007)

[xxxvi] Id.

[xxxvii] UNCLOS, Part XI, § 2, art. 140, 142–44, 148.

[xxxviii] Id. at art. 137, ¶ 2; Id. at art. 140, ¶ 2.

[xxxix] The Mining Code, Int’l Seabed Auth., https://www.isa.org.jm/mining-code.

[xl] UNCLOS, art. 77, ¶ 1.

[xli] Cobalt-rich Ferromanganese Crusts, note 24.

[xlii] Exploration Contracts, Int’l Seabed Auth., https://www.isa.org.jm/exploration-contracts (last visited Feb. 16, 2023).

[xliii] NORI and Allseas Lift Over 3,000 Tonnes of Polymetallic Nodules to Surface, note 28.

[xliv] Id.

[xlv] Status of Treaties: Law of the Sea, United Nations Treaty Collection, https://treaties.un.org/pages/ViewDetailsIII.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=XXI-6&chapter=21&Temp=mtdsg3&clang=_en (last visited Feb. 16, 2023); Member States, Int’l Seabed Auth.,

[xlvi] See Signe Veierud Busch, Establishing Continental Shelf Limits Beyond 200 Nautical Miles by the Coastal State: A Right of Involvement for Other States? 266, 286 (2016); Chapter 2 Resource Rights in the Continental Shelf and Beyond: Why the Law of the Sea Convention Matters to Mineral Law, 64 RMMLF-INST 2, 2-6 (2018).

[xlvii] Danley, supra note 19 at 256 (citing Daisy R. Khalifa, Law of the Sea Goes Public, 55 SEAPOWER 16, 17-18 (2012)).

[xlviii] Eric Tegethoff, Mining Co., ID Conservation Group Partner to Fund Salmon Restoration, Public News Service (Feb. 8, 2023), https://www.publicnewsservice.org/2023-02-08/environment/mining-co-id-conservation-group-partner-to-fund-salmon-restoration/a82811-1; Stevenson and Fixler, supra note 1.

[xlix] Executive Summary: The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions, Int’l Energy Agency, https://www.iea.org/reports/the-role-of-critical-minerals-in-clean-energy-transitions/executive-summary (last visited Feb. 16, 2023).

[l] Id.

[li] Id.

[LE1]Pull quote

Adopt, Don’t Shop: By Legislative Fiat

By Adam P. Karp

Editor’s Note: This article is an excerpt that is reprinted with the publisher’s permission from American Jurisprudent Trials (© 2023 Thomson Reuters). Further reproduction of any kind is strictly prohibited. For further information about this publication, please visit https://legal.thomsonreuters.com/en/products/law-books, or call 800-328-9352.

According to the APPA National Pet Owners Survey (2023-2024), 66% of all U.S. households have a companion animal, with 65.1 million households sharing a home with a dog and 46.5 million households with a cat.[i] Idaho boasts the nation’s highest percentage of dog owners (58%), eighth highest percentage of cat owners (33%), and fifth highest percentage of companion animal owners (70%).[ii] Over six million companion animals enter the approximately 3,500 animal shelters in the United States every year. Best Friends Animal Society[iii] found that homeless animals surrendered to, or impounded by, American shelters die at a rate of at least 350,000 lives per year. In 2016, the year before California became the first state to ban puppy and kitten retail sales, the kill rate was over 1.5 million.[iv]

While some of these millions of animals who have been picked up as strays are reunited to their owners, large numbers are housed in overcrowded facilities at prodigious municipal expense until forcing shelter workers to face the excruciating task of ending lives, not for ailing health, but due to finite resources and out of concern for long-term effects of confinement. Breeding new animals into existence inevitably comes at the expense of those already here and desirous of finding lifetime homes. While Americans have, in some cities, more dogs and cats than human children, there is only so much residential capacity. With a glut of homeless animals, the inexorable march to euthanasia continues.

The Rise in Pet Retail Sales Bans

Municipalities and states who wish to be goal-oriented in staunching this unyielding flow of canine and feline life impose regulatory restrictions, or premiums, on those who harness their reproductive potential rather than curtail it. This is accomplished through mandatory spay/neuter laws, as well as by enacting animal care conditions that seek to ameliorate the oppressive conditions of extensive breeding. Financing impediments also achieve this goal by prohibiting or penalizing predatory solicitations and legal instruments binding consumers to retail installment contracts, leases, loans, and purchase money security interests in the animals. By far the most common legislative tactic is to restrict avenues by which the public may readily acquire bred puppies and kittens, instead incentivizing rescue from a nonprofit or adopting from a shelter.

By cutting off retail supply lines, legislatures reasonably seek to redirect the public to the inventory of homeless pets, thereby lowering animal control and sheltering expenses and furthering the humane goal of stewardship toward animals that society has intentionally or negligently allowed to breed in excessive number. As most consumers shop at pet stores, legislatures naturally look to ban those point of sale transactions at brick-and-mortar storefronts. However, this leaves unaffected direct sales between breeders, whether they occur at the kennel or in a parking lot, advertised via online yard sale sites like Facebook Marketplace or Craigslist, or through website presence.

Yet shutting down pet store sales simply to drive citizens to adopt has been met with repeated constitutional challenges. This is why another rationale surfaced – that the vast majority of animals sold at pet stores come from Commercial Breeding Enterprises (“CBE”) or “puppy mills.” CBEs or puppy mills are large-scale breeding operations notorious for neglectful and abusive conditions related to the factory-type farming of dogs and cats to produce units for filial consumption.

To cripple CBEs and their use of out-of-state municipalities to unload large numbers of puppies and kittens, legislatures have successfully argued that halting retail sales serves to deprive puppy mills of market opportunities, since, after all, puppy mills do not sell directly to the public but, rather, through a series of intermediaries including wholesalers, distributors, dealers, resellers, transporters, and retailers. In so doing, CBEs mask from public view the deplorable conditions of production.

That puppy frolicking in the window of a clean, well-lit, and warm pet store does not faithfully reflect its genesis nor the mistreatment and neglect that follows its parents at an undisclosed location. Aside from cities and counties being moved to take action due to the perfectly understandable considerations for the inhumane treatment of dams and sires, yet another reason for legislative involvement beckons: due to intensive breeding, a number of the milled offspring suffer from congenital abnormalities and behavioral problems not apparent until after sale.

Those maladies may result in unexpected and extreme veterinary expenses to the hoodwinked buyer, or, as is more often the case, surrender of these ailing creatures to municipal shelters, foisting the burden of caring for such hapless beings on taxpayers, and saddling shelter workers with the terrible choice of euthanizing or impounding an animal for a potentially long and costly period, eager for an adoption that is, statistically, unlikely to occur.

Albeit a somewhat circuitous route, the plausible pipeline from puppy mill to pet store to buyer to shelter forges the nexus that supports such bans by shrinking the market in which milled pets may be sold.

Naturally, pet stores have not gone down without a fight, which explains the legal challenges that ensued in the 21st Century, most commonly in the last decade, as pet store bans have taken off like wildfire.

California, Maine, Maryland, Washington, and New York lead, and hundreds of counties and cities all throughout the United States have followed. Indeed, states without a statewide prohibition may as well be regarded as possessing one, such as New Jersey, with 137 municipal bans.[v]

Yet, by and large, except in the case of Arizona, which enacted a law preemptive of Phoenix’s ban,[vi] not a single court has stricken a retail pet sale ban; although a federal district court judge in 2011 did grant a temporary restraining order to enjoin enforcement of the City of El Paso’s law capping the sale price of kittens and puppies at $50 for unaltered and $150 for altered dogs and cats older than eight weeks of age – which suit was later dismissed by a settlement and no further adjudication.[vii] It is extremely dubious that any future court will do so, as nearly every variant of argument has been meticulously fly-specked.[viii]

The predominant challenge to any such law highlights the undeniable discrimination between pet shops, on the one hand, and breeders, animal rescues, and shelters, on the other, taking the form of claims invoking the U.S. Constitution’s Commerce Clause, Equal Protection Clause, Contract Clause, Due Process Clause, and Takings Clause. Federal preemption by the federal Animal Welfare Act (“AWA”) provides yet more grist for dispute, as well as claims of preemption by state law and home rule overreaches. In many respects, litigation over pet retail sales bans read as a redux of the cases upholding state equine slaughterhouse bans.[ix] That said, some permutations have yet to be tested, and if municipalities or states become more emboldened, familiarity with prior cases will prove invaluable.

The Animal Welfare Act

To understand why retail pet sale bans are critical in spite of the federal AWA,[x] one must first understand that retail pet stores are exempt from regulation thereunder. Congress enacted the AWA to insure that pets are provided humane care and treatment, finding it “essential to regulate […] the transportation, purchase, sale, housing, care, handling, and treatment of animals by carriers or by persons or organizations engaged in using them for research or experimental purposes or for exhibition purposes or holding them for sale as pets or for any such purpose of use.”[xi]

To that end, it regulates animal “dealers.”[xii] The AWA definition of dealer excludes retail pet stores.[xiii] Breeders who sell by means where the purchaser has no chance before sale to determine health, such as via the internet, are nonetheless bound to the licensing, inspection, and care standards. This means that breeders selling puppies to consumers in person, such as at flea markets, by the side of the road, or by Craigslist or Facebook yard sale sites, are exempt from the AWA regardless of the size of their breeding operation. Additionally, the AWA does not apply to businesses of de minimis size, such as businesses with four or less breeding female animals.

In response to audits of the federal government’s enforcement of the AWA which demonstrated widespread issues and ineffectiveness,[xiv] APHIS implemented a final rule in September 2013,[xv] which amended 9 CFR Pts. 1 and 2, revised the definition of “retail pet store” to require licensing by breeders in “sight unseen” transactions that do not involve “face-to-face” delivery to customers but typically occur over the internet. Brick and mortar stores remained exempt from licensing and inspection under the AWA. Photos, Skype, webcam, and other electronic methods of communication do not suffice to avoid licensing by such entities.

The rule raised the maximum number of female breeding dogs, cats, or certain species a person could maintain from three to four to be exempt from licensing, provided they sold only offspring from those animals born and raised on their premises for pets or exhibition. 80 FR 3463 (2015) corrected an oversight in the 2013 final rule that neglected to raise the number in one provision of the regulations related to animal purchases by dealers and exhibitors.[xvi] In 2020, APHIS again amended these regulations, but without substantive change to 9 CFR 2.1(a)(3)(iii) [exempting persons with four or fewer breeding female pet animals] or 9 CFR 2.132 [concerning dealer procurement of animals].[xvii]

As of December 2022, APHIS’s Animal Care Program enforces the AWA for 13,200 licensees and registrants. The Animal Care division enforces the AWA and Horse Protection Act (prohibiting soring only).[xviii] In FY 2020, APHRE initiated 1,129 new cases. In FY 2021, the Animal Care program initiated 118 cases for AWA violations, issued 58 official warnings, issued three pre-litigation settlements, and obtained eight administrative orders.[xix] See also USDA FY 2022 Budget Summary, pages 88-91.[xx]

USDA Regulations

The United States Department of Agriculture (“USDA”) and its Animal & Plant Health Inspection Service (“APHIS”)’s implementing regulations[xxi] set the minimum standards for the treatment of certain species in various contexts. Civil and criminal penalties apply.

The USDA created three licensing categories for retail pet sellers:[xxii] a “Class ‘A’ licensee (breeder)” – a dealer subject to AWA licensure “whose business involving animals consists only of animals that are bred or raised on the premises,” a “Class ‘B’ licensee” – a regulated dealer “whose business includes the purchase and/or resale of any animal” including “brokers [… who] negotiate or arrange for the purchase, sale, or transport of animals in commerce,” and “Class ‘C’ licensee” – an exhibitor whose business involves the showing or displaying of animals to the public. Breeders with four or fewer breeding females who sell only offspring from those females need not obtain an AWA license.[xxiii] Businesses covered by the AWA include: “dealers,” typically animal breeders and brokers, auction operators, or those who sell domesticated, laboratory, exotic, or wild animals. Dealers are defined as:

“Any person who, in commerce, for compensation or profit, delivers for transportation, or transports, except as a carrier, buys, or sells, or negotiates the purchase or sale of: Any dog or other animal whether alive or dead (including unborn animals, organs, limbs, blood, serum, or other parts) for research, teaching, testing, experimentation, exhibition, or use as a pet; or any dog at the wholesale level for hunting, security, or breeding purposes. This term does not include: A retail pet store, as defined in this section; and any retail outlet where dogs are sold for hunting, breeding, or security purposes.”[xxiv]

Therefore, Class A dealers deal only in animals they breed and raise; the rest are Class B. Retail pet stores who sell directly to owners, hobbyists, animal shelters, and boarding kennels are not regulated by the federal government. Animal transporters or carriers, such as airlines, railroads, and truck drivers, require a Class T registration, but no license. If registered or licensed, the business or individual must comply with all federal regulations, including recordkeeping and standards of care. Licensing records may be accessed through Animal Care Public Search Tool.[xxv]

The AWA expressly contemplates local regulation[xxvi] and provides that USDA regulations regarding “humane handling, care, treatment, and transportation of animals by dealers” shall not bar any state or locality from promulgating their own additional standards.[xxvii] The USDA has come under criticism for lax enforcement and insufficient standards leading to the proliferation of puppy mills.

The Humane Society of the United States, for instance, has stated: “[the] AWA allows dogs to be kept in cramped, wire-floored cages for their entire lives, churning out litter after litter of puppies for the commercial pet trade.”[xxviii] The Inspector General has found that dogs cared for by USDA-licensed breeders were observed “walking on injured legs, suffering from tick-infestations, eating contaminated food, and living in unsanitary conditions.”[xxix] As a result, many states and localities have imposed restraints on breeders and pet stores.

State Retail Sales Bans

Most pet sale bans originate at the local level, but statewide prohibitions are increasing in prevalence.[xxx] As of March 2022, six states have enacted statewide prohibitions banning retail pet sales. The statewide bans include the following:

In 2017, California became the first state to enact a retail pet sale ban with AB 485, creating Cal. Health & Safety Code 122354.5. This code was subsequently amended in 2020 by AB 2152, known as Bella’s Act, which made it illegal for a pet store not only to sell, or offer to sell, a dog, cat, or rabbit, but from also adopting out such animals. Pet stores wanting to offer live animals would need to put aside space for a public animal control agency, shelter, or 501(c)(3) tax-exempted nonprofit rescue to showcase adoptable animals and the animal must be sterilized prior to adoption and adopted for no more than $500.

In 2022, California passed AB 2380, which prohibited online pet retailers from offering, brokering, referring, or otherwise facilitating a loan or other financing option for adoption or sale of a dog, cat, or rabbit, though it did not apply to a service animal.[xxxi]

California provided a template for other States, such as Maryland in 2018 (Maryland Bus. Reg. Code 19-701 – 703); Maine in 2020 (MRSA 4153); Illinois in 2021 (225 ILCS 605/3.8, 605/3.9), Washington in 2021 (RCW 16.52.360); and New York in 2023 (35-D NYS Agr. & Markets 753-F). The latest state laws make efforts to circumvent bans by “puppy laundering,” the practice of funneling puppies through fake animal rescues with hidden payments, often across state lines, to provide pet stores dogs labeled as “rescues” who are, in fact, bred for sale. The laws do so by prohibiting the shelter or rescue from serving as an affiliative conduit for breeders and brokers.[xxxii]

Boise City Council Ordinance

Most germane to this article is the passage of Ord. 20-21 by the Boise City Council in May 2021. BCC 5-1-22 states:

5-1-22: SALE OF COMMERCIALLY BRED DOGS AND CATS IN RETAIL STORES PROHIBITED:

A. Prohibition: It shall be unlawful for any person to offer for sale any live dog or cat in a retail business within the City, except for dogs and cats obtained from an animal care and control agency, animal care facility, animal shelter, or non-profit rescue that does not breed dogs or cats, or obtain dogs or cats from a person who breeds or resells such animals for payment or compensations.

B. Breeder Exemption: This section shall not prohibit the private breeding of dogs and cats for direct sales between the breeder and the consumer. (Ord. 20-21, 5-11-2021)

Violation of BCC 5-1-22 is a misdemeanor pursuant to BCC 5-1-25(B). Based on the abysmal track record of those challenging such retail pet sale bans, Boise’s laudable ban is virtually guaranteed to be impervious to legal challenge. Thankfully, it helps to close the loophole that allows “rescues” to front for breeders by reselling them under the guise of an exempt nonprofit.[xxxiii]

Conclusion

Laws that ban sales of dogs and cats, and that prohibit breeding altogether, are vital to government operations, public safety, and social equanimity hallmarked by humane stewardship. They will remain needed so long as public consciousness has failed to recognize the hard truth that, by domestication of the canid and felid, and centuries of unbridled animal husbandry, our society has given birth to wholly dependent individuals numbering in the millions of lives to whom we stand in loco parentis. And they, in turn, take millions more lives who have been canned or processed as pet food. We have forsaken our artificially selected companions and thrust upon shelter workers the abhorrent task of what would appear to an objective observer to be “taking out the trash,” except instead of true garbage, the barrels are filled with euthanized, homeless beings.

Adam P. Karp received his J.D. and M.S. in statistics from the University of Washington in 1998 and 2000, respectively. In 2012, the American Bar Association’s Tort Trial and Insurance Practice Section’s Animal Law Committee bestowed upon Mr. Karp the Excellence in the Advancement of Animal Law Award. In 2021, Mr. Karp was elected as a Fellow to the American Bar Foundation. Mr. Karp has practiced animal law since 1999 and is licensed in the States of Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Hawaii. He authored Understanding Animal Law in 2016. He founded the Idaho State Bar’s Animal Law Section.

[i] American Pet Products Association, Pet Industry Market Size, Trends, & Ownership Statistics, https://www.americanpetproducts.org/press_industrytrends.asp.

[ii] Nicole Blanchard, Idaho’s Dog Ownership is the Highest in the U.S.,The Spokesman-Review (Dec. 23, 2018), https://www.spokesman.com/stories/2018/dec/23/idahos-dog-ownership-is-the-highest-in-the-us/; Craig Northrup, Idaho is Top Dog, Coeur d’Alene/Post Falls Press (Jan. 13, 2020), https://cdapress.com/news/2020/jan/13/idaho-is-top-dog-5/.

[iii] Best Friends Animal Society, www.bestfriends.org.

[iv] 2021-2022 APPA National Pet Owners Survey, American Pet Products Association, available at: www.americanpetproducts.org/pubs_survey.asp; The State of Animal Welfare Today, Best Friends Animal Society, https://bestfriends.org/no-kill-2025/animal-welfare-statistics (last visited April 5, 2023).

[v] States with Humane Pet Sales Laws, Best Friends Animal Society, https://bestfriends.org/advocacy/ending-puppy-mills/states-humane-pet-sales-laws (last visited April 5, 2023).

[vi] Puppies ‘N Love v. City of Phoenix, 283 F. Supp. 3d 815 (D. Ariz. 2017).

[vii] Six Kingdoms Enters., LLC v. City of El Paso, No. EP-10-CV-485-KC, 2011 WL 65864 (W.D. Tex. Jan. 10, 2011).

[viii] See, e.g., Just Puppies, Inc. v. Frosh, 565 F. Supp. 3d 665, 687-688 (D. Md. 2021); Park Pet Shop, Inc. v. City of Chicago, 872 F.3d 495, 502-503 (7th Cir. 2017); Perfect Puppy, Inc. v. City of East Providence, 98 F. Supp. 3d 408, 415 (D.R.I. 2015), aff’d in part, appeal dismissed in part, 807 F.3d 415 (1st Cir. 2015); New York Pet Welfare Association, Inc. v. City of New York, 850 F.3d 79, 83 (2d Cir. 2017).

[ix] See, e.g., Empacadora de Carnes de Fresnillo, S.A. de C.V., v. Curry, 476 F.3d 326, 336-37 (5th Cir. 2007) and Cavel Intern., Inc. v. Madigan, 500 F.3d 551 (7th Cir. 2007).

[x] Animal Welfare Act, 7 U.S.C. § 2131 et seq.

[xi] 7 USC § 2131.

[xii] 7 USC § 2132(f).

[xiii] See 9 CFR § 1.1.

[xiv] : See Audit Report 33002-4-SF, USDA and OIG APHIS Animal Care Program Inspections of Problematic Dealers (May 2010), and OIG Audit Report No. 33600-1-CH, USDA (January 1995).

[xv] 78 FR 57227-57250. Docket No. APHIS-2011-0003), Nov. 18, 2013.

[xvi] 9 CFR § 2.132(2).

[xvii] 85 FR 28772, Docket No. APHIS-2017-0062, Nov. 9, 2020.

[xviii] Horse Protection Act, U.S.D.A, https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/ourfocus/animalwelfare/hpa (last modified Aug. 4, 2020).

[xix] Enforcement Summaries, U.S.D.A., https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/ourfocus/business-services/ies/ies_performance_metrics/ies-panels/enforcement-summaries (last modified Feb. 14, 2023).

[xx] FY 2022 Budget Summary, U.S.D.A., available at: https://www.usda.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2022-budget-summary.pdf.

[xxi] 9 CFR § 1.1 – 12.1.

[xxii] 9 CFR § 1.1.

[xxiii] 9 CFR § 2.1(a)(3)(iii).

[xxiv] 9 CFR § 1.1.

[xxv] USDA Animal Care Search Tool, U.S.D.A., https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/ourfocus/animalwelfare/SA_Access_Animal_Care_Search_Tool (last modified Sep. 22, 2020).

[xxvi] 7 USC § 2145(b).

[xxvii] 7 USC § 2143(a)(8).

[xxviii] Puppies ‘N Love v. City of Phoenix, 116 F. Supp. 3d 971, 977-978 (D. Ariz. 2015), judgment vacated, 283 F. Supp. 3d 815 (D. Ariz. 2017).

[xxix] Puppies ‘N Love v. City of Phoenix, 116 F. Supp. 3d 971, at 978.

[xxx] States with Humane Pet Sales Laws, Best Friends Animal Society, https://bestfriends.org/advocacy/ending-puppy-mills/states-humane-pet-sales-laws (last visited April 5, 2023).

[xxxi] Cal. Health & Safety Code § 122191.

[xxxii] Rebecca Carey and Cody Latzer alleged that puppy mill broker J.A.K.’s Puppies and its owners used front “rescue organizations” Rescue Pets Iowa, Bark Adoptions, and Pet Connect Rescue to transport puppy milled dogs to California pet stores and bypass the State ban. The same defendants were sued by the Iowa Attorney General’s Office in 2019. See Carey v. J.A.K.’s Puppies, Inc., et al, Docket No. 5:2021cv02095 (U.S. Dist. (C.D.Cal.) 2021). The suit raised claims under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Statute (“RICO”), the California Unfair Competition Law, the California Consumer Legal Remedies Act, and other state laws.

[xxxiii] To learn more, see Krysten Kenny, A Local Approach to a National Problem: Local Ordinances as a Means of Curbing Puppy Mill Production and Pet Overpopulation, 75 Alb. L. Rev. 379 (2012). See also: An Advocate’s Guide to Stopping Puppy Mills, The Humane Society of the United States, available at: https://www.humanesociety.org/sites/default/files/docs/HSUS_Advocate-Guide_Stopping-Puppy-Mills.pdf; Puppy Mills by State, Bailing Out Benji, https://bailingoutbenji.com/puppy-mill-maps/ (last modified 2020); About Petland and Puppy Mills, The Humane Society of the United States, https://www.humanesociety.org/petland (last visited April 5, 2023); and, The Horrible Hundred, The Humane Society of the United States, https://www.humanesociety.org/horriblehundred (last visited April 5, 2023).

Idaho Conservation League: A Retrospective at 50 Years

By Marie Callaway Kellner, with insights from and appreciation to Jeffrey C. Fereday

The Idaho Conservation League (“ICL”) is Idaho’s oldest and largest state-based, non-profit natural resource conservation organization. Its mission is to create a conservation community with pragmatic, enduring solutions that protect the air we breathe, the water we drink, and the lands and wildlife we love. Founded in 1973, ICL membership has grown from dozens of people to almost 30,000 and includes current members and supporters in all 44 Idaho counties. ICL has 30 staff working from four offices (Sandpoint, McCall, Ketchum, and Boise), and a volunteer Board of Directors who provide geographical representation for all regions of Idaho.

Practitioners of natural resource and environmental law owe a debt of gratitude to those individuals and organizations – including far-sighted political leaders – in the 1960s and 70s who advocated for, and helped pass, the federal statutes that established much of our nation’s legal framework for managing, protecting, and harvesting public natural resources. Yet, just as we see in today’s political and cultural landscape, what was happening at the federal level was in many ways an outgrowth of local sentiments by citizens who were willing to put in the work to make change. The creation of the Idaho Conservation League (“ICL”) in 1973 is Idaho’s homegrown example.

While the lore surrounding ICL’s origins varies regionally, the stories from around the state have a common thread. Whether Coeur d’Alene, Idaho Falls, Boise, Caribou County, Twin Falls, or the Wood River Valley, and whether it was at lunch, a coffee shop, or over a potluck dinner, there was a small group of Idahoans back then with the common desire to do something about protecting Idaho’s environment and its quality of life. Lucky for us today, these folks found each other. They were concerned that Idaho’s Legislature was anti-conservation; they watched growth without safeguards impair open space and wildlife habitat, degrade water and air quality, and threaten the wild places that so greatly contribute to quality of life. They recognized that together their voices would be more effective. But most importantly, they were willing to try. That spirit launched the Idaho Conservation League in 1973.

For 50 years, ICL staff, Board, members, and volunteers have endeavored to carry that commitment forward, providing facts and a consistent voice at the Statehouse, and advocating for things that don’t have a literal voice.

Legends in the Movement

When I joined ICL’s staff as its first ever Water Associate more than a decade ago, I was thrilled to put my relatively recently earned law license to work on behalf of rivers and fish. I have always loved rivers for their inherent beauty and what I deem an analogy for life: serene at times, turbulent at others, yet always flowing and carrying you to places you may not yet know. While my role has evolved and I now work on much more than river conservation, some aspects of working at ICL remain constant, including the opportunity to learn from and continually meet Idahoans who value a healthy environment and our wildest, most pristine places.

Some of the most special work moments I have involve meeting people who were part of the organization’s founding. To realize that 40, 45, or even 50 years on they are still engaged and passionate about ICL’s mission inspires me. ICL is only as strong as its staff, members, and active volunteers, and its earliest ones were legends of Idaho’s environmental protection movement.

After helping found Coeur d’Alene’s Kootenai Environmental Alliance, civic icons, former state senator Mary Lou Reed, and her husband, the late attorney Scott Reed, also anchored the formation of ICL. In late 1973, the Reeds were in the room when what was known as the Boise Lunch Bunch “got down to brass tacks, formed the organization and decided on a name.”[i] Conservation was intentionally chosen over the terms preservation or environmental, and the term league was an acknowledgment that, while there was a staff and board, ICL was actually a league of chapters from around the state. An incomplete list of the people there that day includes photographer Ernie Day, attorney Bruce Bowler, dentist Ken Cameron, and journalist Ken Robison, who is said to have suggested ICL’s initial motto: “[a] non-partisan voice for conservation legislation.”[ii]

ICL’s first Executive Director was Boisean Marcia Pursley, and her first hire was Belle Heffner. Marcia and Belle were organizers extraordinaire who directed the growing volume of ICL volunteers to meaningful work.

Other early leaders who left a mark on ICL via their volunteerism, board, or staff service, legal representation, policy advocacy, or as organizational allies include (among many others) Bruce Bowler, Franklin Jones, John Peavey, Ken Pursley, Nelle Tobias, Matt Mullaney, Tom Davis, Doli Obie, Renee Quick, Jeff Fereday, and Pat Ford.

Notably, two Idaho political stalwarts were in office during ICL’s early years: Gov. Cecil Andrus and Sen. Frank Church. Aptly described by Fereday as “two, once-in-a-lifetime politicians,” they were lions in the environmental movement who had “a bones-deep appreciation for clean air, wildlife, wild places, and free-flowing rivers.”[iii] They provided inspiration and focus for ICL early on just as their legacy continues to inspire ICL today.

Advocacy From the Beginning

ICL is not a law firm; it’s an advocacy organization. That being said, several ICL staff are attorneys who practice primarily in state administrative fora. If ICL litigates in federal court, it typically works with outside – often pro bono – legal counsel. ICL’s advocacy also comes in the form of lobbying, education, public engagement, and policy development with state and federal agencies. Each of these tools is used strategically and, ideally, at the right time. ICL’s long-time Executive Director Rick Johnson (now retired) once said, “[c]onservation success is based on windows of opportunity. These openings are sometimes rare and fleeting. The art of conservation is recognizing the opening and getting through it, usually in some policy forum, where achievement can be made.”[iv]

Two of ICL’s earliest windows of opportunity were advocating for thoughtful growth through land use planning and mandating public disclosure by lobbyists. In his recent essay, “Memories of ICL, 1973-77”[v] Jeff Fereday – who in addition to being a longtime Idaho attorney was an early ICL volunteer and its second Executive Director – shared Marcia Pursley’s recollections about the land use planning fight:

“When the first ICL Board met in November 1973, rampant and unregulated growth were hammering Idaho communities. Land use planning and zoning were local options, not statewide requirements. In 1970 or so, Boise City had hired planning staff to oversee ‘planned growth,’ but backlash against these efforts was immediate and personal. Boise planning staff were being threatened by people who contended they could do anything, anytime, with their property, that land planning and zoning was a communist plot, and that the Boise City planners should, in so many words, ‘get the hell out of town.’”

Governor Cecil Andrus recognized that Idaho’s growth needed safeguards, and a commission he created to study solutions proposed the Local Planning Act in the 1974 legislative session, an early version of our current Land Use Planning Act.[vi] What happened next is recollected by Fereday:

“With such widespread support, one might assume the measure would be odds-on to pass, and ICL and its allies worked hard to achieve that. But there were obstacles. The bill stalled in the Idaho Senate. A filibuster by then Minority Leader and later Idaho governor, John Evans, broke the logjam. ICL staff and volunteers sat in the gallery lending moral support. Another challenge was that a Senate committee chair used Idaho state letterhead for a letter addressed to all ‘Fellow Realtors’ urging opposition to the bill. To counter that, ICL volunteers packed his committee room, standing body to body behind the members. However, late in the session, a group of companies (including Idaho Power, Morrison Knudsen, and the realtors and homebuilders’ associations) sent in a brigade of lobbyists, many of them on a stealth basis, who persuaded legislators to kill the bill.

Frustrated and alarmed, ICL staff now felt the sting of a situation that undermined representative democracy: the fact that a business or other entity could work completely behind the scenes at the Legislature while disclosing nothing about backers and financial supporters. Marcia, Belle, and the ICL Board understood that this problem would continue to frustrate citizen action on every issue unless something were done. Marcia’s response was immediate, and aimed directly at using democracy itself.

As soon as the 1974 legislative session ended, Marcia and Senator John Peavey created a volunteer committee to launch a citizens’ initiative to put on the November 1974 ballot a proposed new statute, dubbed the Sunshine Law,[vii] that would require lobbyists to register and reveal their employers, and would mandate financial disclosures for both lobbying efforts and election campaigns. Ken Pursley wrote the proposed new statute, John Peavey chaired the statewide effort, and Mary Mech of the League of Women Voters staffed signature gathering. Boise legislator Bill Onweiler (R) enthusiastically supported the initiative, and his wife, Corki Onweiler, chaired the Ada County signature gathering effort. In those days, before the Legislature made the initiative process as vexingly difficult as it is today, signatures in a small number of counties could put a measure on the ballot. Despite the short timeframe, the proponents succeeded, and, once it was on the ballot, Governor Andrus supported it. As did Idaho voters in the November 5, 1974 election – by 77.56%.”[viii]

Keeping Coal Out of Idaho

Idaho’s Sunshine Law exemplifies ICL as a champion for good ideas and a fulcrum for volunteer citizen effort. Another early priority, preventing the Pioneer Coal Plant from being built on the desert between Boise and Mountain Home, exemplifies ICL’s commitment to oppose bad ones.

Proposed by Idaho Power to address what it projected would be necessary to meet growth, Pioneer was a proposed 1,000 mega-watt coal fired power plant to be located about 20 miles south of Boise. Organizing against what would have been Idaho’s first coal fired power plant required the fledgling conservation organization to grow up fast. As recalled by Fereday, “[c]ountering Idaho Power’s message required hard-nosed, tireless work; fact-finding, self-education, work at the Legislature, a vigorous presence in the news, and persuasion at the state agencies. It required consulting experts and researching federal clean air matters, utility regulation, electrical transmission, the northwest energy system, and the economics of power sales and consumption.”[ix]

ICL staff and volunteers raised funds to host energy awareness workshops around the state. They wrote Letters to the Editor and created petitions opposing the coal fired plant. They pitched stories to Idaho newspapers and the regionally acclaimed High Country News. They organized with allies like the League of Women Voters and the Idaho Medical Association. There was even a TV debate between then-ICL Executive Director Fereday and Idaho Power’s CEO Albert Carlsen. Much as still happens today, ICL used as many tools in the toolbox as it could. And luckily for Idaho, its air quality, and its energy economy, these efforts were successful. In September 1976, the Idaho Public Utilities Commission denied Idaho Power’s application to build Pioneer. To this day, Idaho still has no instate coal fired power.

Protecting For Perpetuity

In the almost 50 years since, ICL has been at the table when natural resource issues are on the menu. The Owyhee Canyonlands Wilderness and its attendant Wild & Scenic Rivers reaches;[x] the Cecil D. Andrus White Clouds Wilderness;[xi] the Central Idaho Dark Sky Reserve;[xii] the Frank Church-River of No Return Wilderness;[xiii] the preservation of Box Canyon in the mid-Snake River;[xiv] citizens suits under the Clean Water Act[xv] and the Endangered Species Act;[xvi] and much more. And beyond all this, of course, is ICL’s day-to-day attention to and dissemination of information to the public about environmental issues facing Idaho.

Onward!

As ICL enters its second 50 years, much remains to be accomplished. People like me, with the good fortune to work here now, do our best to embody the goals of ICL’s founders, early staff, and volunteers. If we are successful, 50 years from now those who come after us will have the opportunity to reflect on the relevance and importance of this organization and all it has done to shine a light on good governance, protect in perpetuity the most worthy of places, fight for public and environmental health by protecting air and water, and be a voice for the fish and wildlife that don’t otherwise have one.

Marie Callaway Kellner is the Idaho Conservation League’s Conservation Programs Director. Previously, she was a law clerk to the Hon. Ron Wilper in Idaho’s Fourth Judicial District and the Hon. Mikel Williams in the U.S. District Court. Prior to that, she was a river guide and teacher. she holds a J.D. from the University of Idaho College of Law, a B.A. and M.Ed. from the University of Tennessee, and she is grateful to advocate for some of the most extraordinary landscapes on Earth, right here in Idaho.