Category: Digital Advocate

The United States Attorney’s Office New Corporate Voluntary Self-Disclosure Policy: Clear Benefits for Good Corporate Citizens

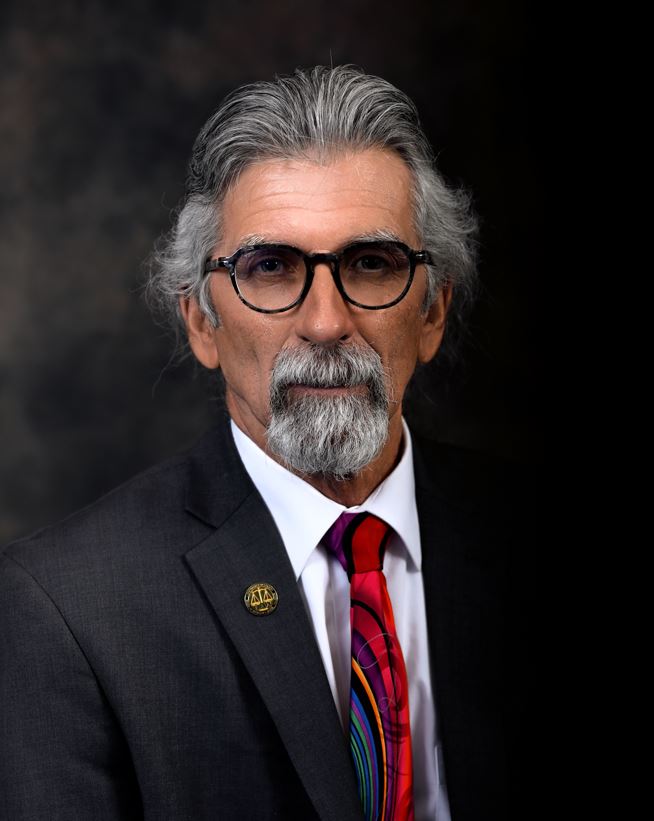

Joshua D. Hurwit, United States Attorney

Kevin T. Maloney, Deputy Criminal Chief

Let’s say you represent a company and determine that an official of that company has committed criminal wrongdoing. What do you do? Self-report the violations or wait for government investigators to knock on the door? There are risks to doing both. In this article, we introduce the United States Attorney’s Office’s new Corporate Voluntary Self-Disclosure Policy (the “VSD Policy”), which is designed to minimize the risks to companies of self‑reporting by rewarding companies that have built – or are taking concrete steps to build – cultures of compliance.

The VSD Policy rewards good corporate citizenship, but also promotes the enhanced and efficient investigation and prosecution of white-collar criminals. It identifies a path for corporate counsel and the defense bar to earn significantly reduced penalties for their corporate clients. It should allow companies to continue to operate and to benefit the public even when they uncover wrongdoing. At the same time, resolving corporate wrongdoing without a guilty plea by the company should not be confused with leniency toward individuals who commit fraud or other crimes. Such individuals will be investigated and held accountable, as always, pursuant to the Department of Justice’s (“DOJ”) principles of federal prosecution.

Clarity and Consistency: Background on the New Voluntary Self-Disclosure Policy

In October 2021, Deputy Attorney General (“DAG”) Lisa Monaco led a top-to-bottom review of the DOJ’s corporate enforcement policies and priorities. DOJ leaders not only identified best practices from within the DOJ, but also sought input from the business community, the defense bar, consumer advocacy groups, and others. This rigorous assessment led to the DAG’s announcement in September 2022 of a set of updated corporate enforcement policies.[i] The policies aim both to ensure that individual accountability remains a top priority for the DOJ and to provide transparency and predictability for companies so they can benefit from being good corporate citizens.

As part of the policies – and in order to provide consistency and predictability across the country with respect to voluntary self-disclosure by companies – the United States Attorney’s Office community developed the Voluntary Self-Disclosure Policy, which is now in effect in every United States Attorney’s Office (“USAO”) in the country.[ii]

The VSD Policy’s goals can be summarized as follows:

- To reward and incentivize corporate responsibility and a culture of compliance by clarifying and standardizing USAO policies on voluntary disclosure and corporate cooperation;

- To achieve individual and corporate accountability by motivating companies (i) to build compliance programs capable of identifying misconduct and (ii) to expeditiously and voluntarily disclose misconduct to the government; and

- To provide transparency and predictability to companies and the defense bar about the benefits and potential outcomes in cases in which companies voluntarily self-disclose misconduct, fully cooperate, and timely and appropriately remediate wrongdoing.

Taken as a whole, then, the VSD Policy seeks to enhance white-collar crime enforcement in a clear and consistent manner that rewards companies for being good corporate citizens.

Clear Benefits: The Voluntary Self-Disclosure Policy’s Provisions

For companies, the primary benefit of the Voluntary Self-Disclosure Policy is that, when the USAO determines that the VSD requirements are satisfied, the USAO will not seek a guilty plea from the self-reporting company. Instead, the USAO could decline the case or enter into a non-prosecution or a deferred prosecution agreement.

So, what are the standards that a company needs to meet in order to obtain this benefit under the VSD Policy?

First, the disclosure to the USAO must be voluntary. Voluntary means that the company did not have a preexisting obligation to disclose, such as pursuant to regulation, contract, or a prior resolution with the DOJ (e.g., a non-prosecution agreement or deferred prosecution agreement). The disclosure must also come from the company, not from a whistleblowing employee or a through a qui tam action.

Second, the disclosure must occur before an imminent threat of disclosure or government investigation, before any misconduct is publicly disclosed or otherwise known to the government, and within a reasonably prompt time after the company becoming aware of the misconduct. The burden is on the company to demonstrate timeliness.

Third, the disclosure must include all relevant facts concerning the misconduct that are known to the company at the time of the disclosure. The VSD Policy recognizes that a company may not know all relevant facts at the time of initial disclosure. Accordingly, a company may satisfy the disclosure standard through a preliminary investigation and disclosure, with timely follow-up to preserve and collect relevant information and to update the USAO.

Fourth, no aggravating factor set forth in the VSD Policy, including those in the following, can apply to the misconduct. Thus, the misconduct may not: pose a grave threat to national security, public health, or the environment; deeply pervade the company; or involve current executive management of the company.

Note that the presence of one or more aggravating factors does not necessarily mean that a guilty plea will be required. But it does mean that the VSD Policy does not apply and the USAO will assess the relevant facts and circumstances to determine the appropriate resolution.

Finally, the company must fully cooperate with the government and agree to remediate the misconduct at issue appropriately. Appropriate remediation includes, but is not limited to, the company agreeing to pay all disgorgement, forfeiture, and restitution resulting from the misconduct at issue.

If the USAO determines that these requirements are met, it will not require a corporate guilty plea. Moreover, if a criminal fine is required as part of a corporate resolution (e.g., a deferred or non-prosecution agreement), that fine will not exceed 50% off the low end of the applicable fine range under the United States Sentencing Commission Guidelines Manual.

Moreover, even if an aggravating factor precludes application of the VSD Policy, a company can still benefit by timely and fully self-reporting. Such circumstances may well lead the USAO to recommend to a sentencing court, at least 50% and up to a 75% reduction off the low end of the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines’ fine range. And the USAO may not require that the court appoint a monitor if the company has, at the time of resolution, implemented and tested an effective compliance program. Thus, it’s important for companies to know that the potential existence of an aggravating factor will not preclude them from getting a material benefit in any potential resolution if they otherwise comply with the VSD Policy.[iii]

Putting the Voluntary Self-Disclosure Policy into Practice: Real World Examples

The USAO will decide whether a company has satisfied the Voluntary Self-Disclosure Policy on a case-by-case basis through a careful assessment of the disclosure’s circumstances. Understandably, corporate counsel and the defense bar seek real world examples to guide their decision-making and the advice that they give to clients.

With the VSD Policy being only months old, we cannot yet point to a case that has been fully vetted through the policy and made public. But the DOJ has long used non-prosecution agreements and deferred prosecution agreements for companies in appropriate circumstances, and we can point to several such agreements that might well fall under the VSD Policy. These cases provide guidance to companies and the defense bar as they consider whether to voluntarily disclose wrongdoing to our office.

- The ABB entities corporate resolution demonstrates the value of a strong compliance program and an early decision to disclose.[iv] ABB had entered prior resolutions with the DOJ based on Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (“FCPA”) violations and, as a result, implemented a compliance program. That program detected further misconduct – an ABB employee bribed a high-ranking official at South Africa’s state-owned energy company. Although the media publicized the misconduct, at the time of media publication, ABB had already scheduled a disclosure meeting with the Criminal Division of the DOJ. The DOJ favorably recognized that ABB’s detection resulted from its compliance program, that it intended to promptly disclose, and that it was fully cooperating and remediating the misconduct, including by voluntarily making employees available for interviews and producing documents located outside the United States. Balancing this positive conduct against the prior violations resulted in a deferred prosecution agreement for ABB, the parent company. Two subsidiaries pleaded guilty. South African authorities brought corruption charges against the offending individual corporate official.

- The VSD policy can provide companies with advantages in acquisitions of other companies, as seen in the prosecution declination of a French aerospace company, Safran SA.[v] In post-acquisition due diligence of a new subsidiary, Safran discovered that the subsidiary had bribed a Chinese consultant. Safran promptly disclosed the FCPA violations. The DOJ declined prosecution because the company had voluntarily self-disclosed, cooperated, remediated, and agreed to disgorge the approximately $17 million of ill-gotten gains.

- The VSD policy will be a valuable tool in health care fraud cases as well. In 2021, National Spine and Pain Centers, LLC (“NSPC”) entered into a non-prosecution agreement with the USAOs for the Central District of California and the Southern District of California.[vi] NSPC agreed to pay $5.1 million to the government to resolve charges for receiving payments in violation of the Anti-Kickback Statute. NSPC admitted that physicians received illegal kickback payments under the guise of a clinical research program and submitted inflated timesheets, resulting in overpayments from Medicare. The USAOs considered NSPC’s anti‑kickback‑focused compliance program, its early engagement and cooperation, and remedial measures taken prior to its knowledge of the criminal investigation. Nine individuals were charged in connection with the alleged scheme in the Central District of California in a related case.

A contrary example may also be helpful.

- The case of Balfour Beatty Communities is a cautionary tale.[vii] Balfour, one of the largest providers of privatized military housing, lied about required repairs and, as a result, pocketed millions of dollars in performance bonuses. The company did not disclose or cooperate. After the DOJ investigated, the company entered a guilty plea. The Court sentenced Balfour to pay over $33.6 million in criminal fines and over $31.8 million in restitution to the U.S. military, to serve three years of probation, and to engage an independent compliance monitor for a period of three years. As DAG Monaco noted, Balfour’s lack of adequate compliance programs and its failure to voluntarily self-disclose misconduct resulted in the company’s payment of “a price that outweighs the profits they once reaped.”[viii]

The prior examples illustrate how the USAO may view companies that implement robust compliance programs, recognize criminal wrongdoing, and try to do the right thing by disclosing to the government as soon as possible: exactly what the VSD Policy promotes.

Conclusion

The Voluntary Self-Disclosure Policy’s incentives represent the DOJ’s renewed efforts to enlist companies in achieving good corporate citizenship throughout the country in all sectors and industries. In Idaho, we hope that companies will step up and own up when misconduct occurs. When companies do, they will have far better and more predictable outcomes under the VSD policy. And all of Idaho will benefit from the resulting enhanced accountability for individual wrongdoers.

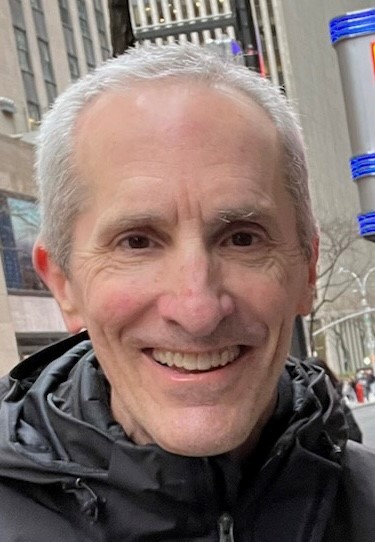

Joshua D. Hurwit was confirmed in June 2022 as the 32rd presidentially appointed United States Attorney for the District of Idaho. From 2012 to his appointment as U.S. Attorney, Mr. Hurwit served as an Assistant United States Attorney for the District of Idaho, where he primarily prosecuted financial, public corruption, and environmental crimes. Prior to joining the U.S. Attorney’s Office, Mr. Hurwit worked at international law firms in San Francisco and New York. From 2007 to 2008, he clerked for U.S. District Judge Naomi Reice Buchwald in the Southern District of New York. Mr. Hurwit received his B.A. from Stanford University in 2022 and his J.D. from Harvard Law School in 2006.

Kevin T. Maloney serves as an Assistant United States Attorney with the United States Attorney’s Office for the District of Idaho. He is the Deputy Criminal Chief supervising fraud and Project Safe Childhood. He has specialized experience in asset forfeiture, fraud, health care, FDCA (Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act), and digital evidence. His last two trials involved distribution of oxycodone by a physician without a legitimate medical purpose and fraudulent billing by a dental hygienist who impersonated a dentist. Previously, Mr. Maloney practiced civil litigation with a private firm. He started his career as an Ada County Deputy Prosecutor, where he also lobbied for the Idaho Prosecuting Attorney’s Association. Mr. Maloney received his J.D. from Notre Dame Law School and a bachelor’s in economics and Spanish from the University of Illinois. Outside of the office, he enjoys skiing, mountain biking, and tennis.

[i] https://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/deputy-attorney-general-lisa-o-monaco-delivers-remarks-corporate-criminal-enforcement.

[ii] https://www.justice.gov/corporate-crime/voluntary-self-disclosure-and-monitor-selection-policies.

[iii] While the VSD sets forth these benefits where voluntary self-disclosure occurs, companies (like individuals) can receive benefits when they chose to cooperate with the government even though they did not timely disclose. In such cases, the USAO will continue to evaluate all facts, circumstances, and the law, as required by the Justice Manual, and use discretion in determining the appropriate resolution, which includes the amount of any fine.

[iv] https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/abb-agrees-pay-over-315-million-resolve-coordinated-global-foreign-bribery-case.

[v] https://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/assistant-attorney-general-kenneth-polite-jr-delivers-remarks-georgetown-university-law; https://www.justice.gov/criminal-fraud/file/1559236/download.

[vi] https://www.justice.gov/usao-sdca/pr/pain-management-organization-pays-51-million-settle-criminal-medicare-kickback.

[vii] https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-announces-global-resolution-criminal-and-civil-investigations-privatized.

[viii] https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-announces-global-resolution-criminal-and-civil-investigations-privatized.

From the Courts: Highlights of Rule Amendments for 2023

Lori A. Fleming

Staff Attorney and Reporter

Idaho Supreme Court Rules Advisory Committees

The following is a list of rule amendments approved by the Idaho Supreme Court between July 2, 2022, and May 1, 2023. Please note that additional amendments may have been approved after this article was submitted for publication on May 1, 2023. Refer to the Idaho Supreme Court website for an up-to-date list of orders amending the Idaho Court Rules. See http://www.isc.idaho.gov/recent-amendments. Also, be sure to check the Idaho State Bar weekly E-Bulletin for your chance to comment on any future proposed amendments before they are adopted.

Idaho Court Administrative Rules

Rule 32. Judicial Records Exempt from Disclosure. Idaho Court Administrative Rule 32(g) identifies a number of judicial records that are exempt from public disclosure. There have been two recent amendments to this rule. First, an April 1, 2023 amendment added new subsection (g)(29), which exempts from public disclosure “Pending grant applications and attachments submitted to the Guardian Ad Litem Grant Review Board for consideration of grant funding authorized under Title 16, Chapter 16 Idaho Code.” The new subsection clarifies that, once a grant application has been approved and grant funds have been awarded, the application and attachments are no longer exempt. Second, a May 1, 2023 amendment to subsection (g)(10) deleted the general reference to “Mental commitment case records” and more specifically identified the exempt records as “All records of proceedings relating to hospitalizations pursuant to Idaho Code sections 66-326, 66-329, 66-406, 16-2413, and 16-2414.”

Rule 43a. Administrative Conference. Until recently, the Administrative Conference was required to meet four times each year, or according to such other schedule as the Administrative Conference may adopt. Effective April 10, 2023, subsection (b) of Idaho Court Administrative Rule 43a was amended to provide that the Administrative Conference shall meet three times each year, or according to such other schedule as may be determined by the Idaho Supreme Court.

Rule 45. Cameras in the Courtroom. Idaho Court Administrative Rule 45 governs the use of cameras and other audio/visual equipment in the courtroom during trial court proceedings. The rule was amended on January 9, 2023. Some parts of the rule were reworded and reorganized, but no significant substantive changes were made.

Rule 46a. Cameras in the Supreme Court Courtroom. Idaho Court Administrative Rule 46a governs the use of cameras and other audio/visual equipment in the courtroom during proceedings before the Idaho Supreme Court and Idaho Court of Appeals. Effective January 9, 2023, the rule was amended to clarify that approval to video record or photograph a Supreme Court or Court of Appeals proceeding must be obtained from the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court or the Chief Judge of the Court of Appeals at least one business day in advance of the hearing. Pursuant to the amended rule, the requirement for advance approval does not apply to the live broadcast of Supreme Court proceedings provided on an ongoing basis by Idaho Public Television/Idaho In Session. Additionally, the amended rule states that preference will be given to restricting live coverage of Supreme Court proceedings to the Idaho Public Television broadcast, and that Idaho Public Television will provide a video and audio feed to other media. Finally, the amended rule incorporates the I.C.A.R. 45 guidelines relating to equipment, dress, pooling of coverage, limits on coverage, and other matters that are relevant to appellate proceedings.

Rule 46b. Cameras in Courtroom During Terms of Court Outside of Boise. Idaho Court Administrative Rule 46b governs media coverage of Supreme Court and Court of Appeals proceedings held outside of the Supreme Court courtroom. The January 9, 2023 amendments to this rule largely mirror the amendments to I.C.A.R. 46a. Specifically, amended Rule 46b requires individuals wishing to video or photograph proceedings to obtain approval at least one business day in advance of the hearing; states that the advance approval requirement does not apply to live broadcast of Supreme Court proceedings provided on an ongoing basis by Idaho Public Television/Idaho in Session; and incorporates the I.C.A.R. 45 guidelines relating to equipment, dress, pooling of coverage, limits on coverage, and other matters that are relevant to appellate proceedings.

Rule 62(c), Appendix A. Juror Questionnaire. The “Disqualification” section of the Juror Questionnaire contained in Appendix A to Idaho Court Administrative Rule 62(c) was amended on March 9, 2023. The disqualification criteria were reworded and reorganized, but no substantive changes were made.

New Rule 100. Procedural Rules for Mental Commitments. On May 1, 2023, the Court adopted new Idaho Court Administrative Rule 100. The new rule sets forth the procedures that must be followed in mental commitment cases. Subsection (a) of the rule states that, whenever a person is taken into custody or detained by a police officer or medical staff member without a court order pursuant to Idaho Code section 66-326(1) or Idaho Code section 16-2413, the prosecuting attorney must electronically file the evidence supporting the statutory basis for the detention within 24 hours of the time the person was placed in custody or detained. Subsection (b) of the rule states that, whenever the court issues a temporary custody order and requires examination by a designated examiner, the designated examiner has 24 hours from the examination to report his/her findings to the prosecuting attorney who, in turn, has no more than 24 hours to file such findings with the court.

Idaho Criminal Rules

Appendix A. Guilty Plea Advisory Form. Paragraph 18.b of the Guilty Plea Advisory form found in Appendix A of the Idaho Criminal Rules erroneously stated that a defendant pleading guilty pursuant to a binding plea agreement will be allowed to withdraw his/her plea and proceed to a jury trial. Effective January 27, 2023, paragraph 18.b was corrected to state that a defendant pleading guilty pursuant to a binding plea agreement will not be allowed to withdraw his/her plea and proceed to a jury trial.

Idaho Misdemeanor Criminal Rules

Rule 13. Misdemeanor Bail Bond Schedule. The Misdemeanor Bail Bond Schedule found in Idaho Misdemeanor Criminal Rule 13(b) is divided into a number of different offense categories (e.g., motor vehicle offenses; license, registration, and insurance offenses; fish and game offenses; etc.). In 2022, a generic “Other” designation, with an accompanying default bond amount of $300, was added to the end of each offense category. The purpose of the “Other” designation is to account for any offenses that fall within an offense category but that are not specifically listed in the bail bond schedule. Effective January 4, 2023, the “Other” designation and default $300 bond amount included at the end of the Fish and Game offense category was removed because it conflicted with the prefatory language of I.M.C.R. 13(b)(5), which states that the amount of bail for any alleged fish or game offense not specifically listed in the bail bond schedule “shall be the sum of $191.00.”

Lori A. Fleming received her Juris Doctorate from the University of Idaho College of Law in 1998. After law school, she completed a two-year clerkship for United States Magistrate Judge Mikel H. Williams. Following her clerkship, she worked for almost 20 years as a Deputy Attorney General in the Appellate Unit of the Criminal Law Division of the Idaho Attorney General’s Office. She has been the Staff Attorney for the Idaho Supreme Court since September 2019.

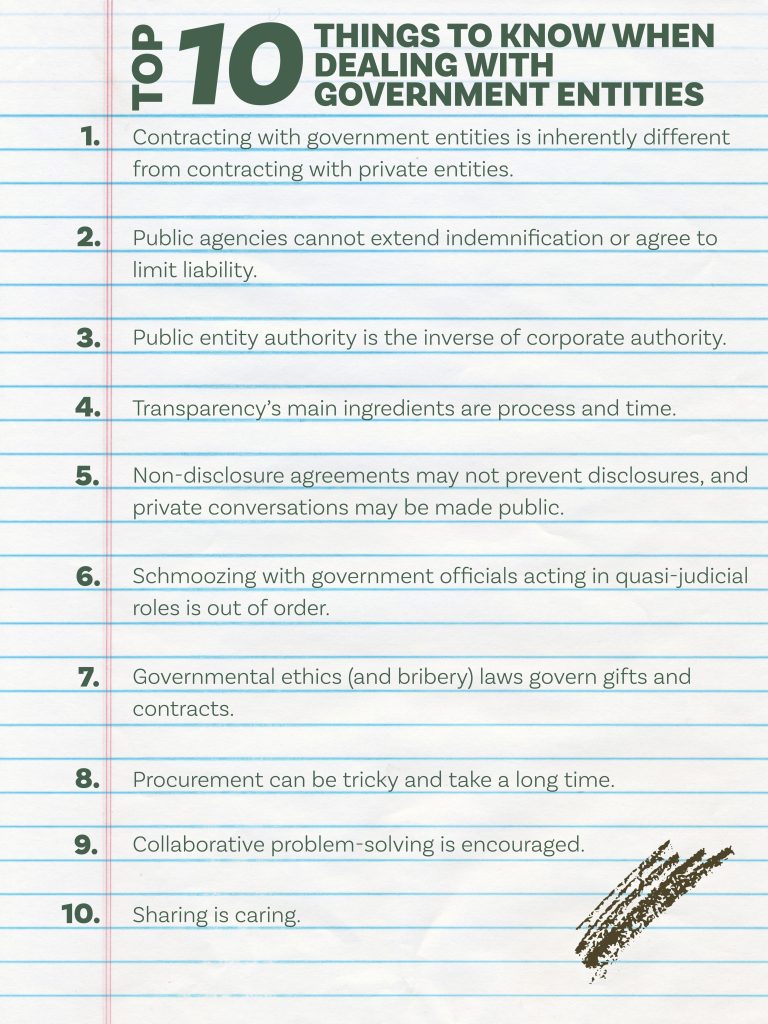

Buyer Beware: Potential Ethical Perils of Municipal Procurement

Kurt J. Starman

Cities and other local government agencies frequently contract for goods, services, and public works construction. These contracts are often approved with little scrutiny. In many cities, procurement contracts are routinely placed on the consent agenda and approved without discussion. As explained in the following, however, there are potential ethical and legal perils which public officials and municipal attorneys must keep in mind when procuring goods, services, and public works construction. Violations of Idaho law may result in civil penalties, criminal penalties, or both. Thus, public officials and municipal attorneys must be knowledgeable about these potential perils.

This article is intended to highlight some common procurement concerns and, more importantly, emphasize the notion that cities must adhere to high ethical standards. To that end, this article addresses conflicts of interest, prohibitions on contracting with public officials, prohibitions on splitting purchases, and bidding requirements for public works construction.

Conflicts of Interest

The Ethics in Government Act, which is found in Chapter 4, Title 74, Idaho Code, centers on conflicts of interest. The Act is based, in large part, on the premise that public service is a public trust. Therefore, the Act is intended to ensure honesty and impartiality in state and local government.

A conflict of interest is defined as an official action, decision, or recommendation by “a public official, the effect of which would be to the private pecuniary benefit of the person or a member of the person’s household, or a business with which the person or a member of the person’s household is associated [. . .].”[i] The term “public official” includes elected officials, appointed officials, public employees, and certain consultants.[ii]

If a conflict of interest exists, a public official must disclose the conflict prior to taking an official action or making a formal decision or recommendation.[iii] The method of disclosure varies. An elected official, for example, must disclose the conflict of interest prior to acting on a matter and follow the “rules of the body of which he/she is a member [. . .].”[iv] Appointed officials, public employees, and consultants must “prepare a written statement describing the matter required to be acted upon and the nature of the potential conflict, and [. . .] deliver the statement to his appointing authority.”[v]

The Ethics in Government Act does not preclude a public official from taking an action, rendering a decision, or making a recommendation. Instead, the Act requires the public official to (1) disclose the conflict of interest and (2) adhere to the city’s rules concerning conflicts. A public official who fails to comply with the disclosure requirements, however, is subject to civil penalties.”[vi]

Prohibition Against Contracts with Officers Act

The Prohibition Against Contracts with Officers Act, contained in Chapter 5, Title 74, Idaho Code, includes prohibitions concerning contracts involving public officers.[vii] Under the Act, public officers “must not be interested in any contract made by them in their official capacity, or by any body or board of which they are members.”[viii] Additionally, public officers “must not be purchasers at any sale nor vendors at any purchase made by them in their official capacity.”[ix] Any contract made in violation of these provisions “may be avoided at the instance of any party except the officer interested therein.”[x]

Stated differently, a contract made in violation of the Act is voidable by any party to the contract other than the offending public officer. Moreover, an “officer charged with the disbursement of public moneys, who is informed by affidavit that any officer whose account is to be settled, audited, or paid by him, has violated any of the provisions of [the Act], must suspend such settlement or payment, and cause such officer to be prosecuted for such violation.”[xi] A violation of the Act is a misdemeanor, punishable by a fine of up to $1,000 and incarceration.[xii]

There are two notable exceptions to the general prohibition against contracting with public officers. Under the first exception, a public officer with a “remote interest” may enter into a contract with that officer’s city. However, the public officer must disclose the remote interest, the matter must be noted in the minutes, and the city council must “authorize[], approve[], or ratif[y] the contract in good faith by a vote of its membership sufficient for the purpose without counting the vote or votes of the officer having the remote interest.”[xiii]

There are four categories of remote interests.[xiv] The first category pertains to non-salaried officers of not-for-profit corporations. The second category concerns employees and agents of a contractor, but only when they receive a fixed wage or salary. The next category covers landlords or tenants of a contracting party. The final category pertains to public officers holding a limited number of shares in a contracting corporation.

Even if a public officer falls into one these four categories, however, the officer cannot “influence or attempt to influence any other officer of the board [. . .] to enter into the contract.”[xv] A violation of this provision is a misdemeanor.[xvi] Additionally, the contract in question is, as a matter of law, void.[xvii]

The second exception to the general prohibition against contracting concerns uncompensated public officials.[xviii] Under the Act, an uncompensated public official “shall not be prohibited from having an interest in any contract made or entered into by the board of which he is a member, if he strictly observes the procedure set out in Section 18-1361A, Idaho Code.”[xix] Section 18-1361A, in turn, lists four requirements. First, the contract must be competitively bid and the public servant (or the public servant’s relative, if applicable) must submit the low bid. Second, the public servant may not participate in the preparation or approval of the bid specifications or contract. Next, the public servant must disclose, in writing, his/her interest and intent to bid on the contract. Finally, the public servant must adhere to all other procurement statutes.

Bribery and Corrupt Influence Act

The Bribery and Corrupt Influence Act, found in Chapter 13, Title 18, Idaho Code, includes additional prohibitions concerning contracts involving public servants.[xx] Similar to the Prohibition Against Contracts with Officers Act, a public servant cannot “[b]e interested in any contract made by him in his official capacity, or by any body or board of which he is a member, except as provided in Section 18-1361, Idaho Code.”[xxi] The exceptions in Section 18-1361 apply when there are a limited number of potential suppliers and (1) the contract relates to a disaster or (2) procedures comparable to those found in Section 18-1361(A) are utilized, as delineated previously.

Similar to the Prohibition Against Contracts with Officers Act, any public servant who violates the Bribery and Corrupt Influence Act is guilty of a misdemeanor and subject to fines and incarceration.[xxii] Moreover, a violator “may be required to forfeit his office and may be ordered to make restitution of any benefit received by him to the governmental entity from which it was obtained.”[xxiii] If the violator is a public officer, forfeiture of office is automatic.[xxiv]

Circumventing Competitive Bidding Requirements

“Splitting a purchase” generally involves a single procurement which is “split” into two or more smaller transactions to circumvent competitive bidding requirements. A public official may not knowingly or willfully “split or separate purchases or work projects with the intent of avoiding compliance with” Idaho’s procurement statutes.[xxv] If this occurs, “the public entity which the officer or employee serves” is liable for civil penalties of up to $5,000 for each offense.[xxvi]

Public Works Contracts

The statutes described previously also apply, of course, to contracts for public works construction. Importantly, however, there are additional prohibitions specific to public works contracts.

Under Idaho law, it is “unlawful for any person to engage in the business or act in the capacity of a public works contractor within this state without first obtaining and having a license” unless an exemption applies.[xxvii] A common exemption, for example, is a public works project with an estimated cost of less than $50,000.[xxviii]

Moreover, when submitting a bid to a city for public works construction, a general contractor must list all subcontractors and their license numbers.[xxix] Before including a subcontractor on the list, the general contractor must receive some form of “communication” from the subcontractor.[xxx]

If a city enters into a contract for public works construction with an unlicensed or improperly licensed contractor, or knowingly awards a public works contract based on a bid that does not properly list all subcontractors, the city is a subject to an administrative fine of up to $5,000 per violation.[xxxi] If the Administrator of the Idaho Division of Building Safety receives a verified complaint from a licensed contractor about a potential violation, the Administrator is required by law to investigate the matter.[xxxii]

As explained, the offending city must pay any administrative fines – not the public officer. Nevertheless, public officers are subject to criminal penalties. Any “public officer who knowingly lets a public contract to [a contractor] who does not hold a license as required by [Idaho law] or knowingly fails to comply with the [statutes concerning the listing of subcontractors] shall be guilty of a misdemeanor [. . .].”[xxxiii]

Conclusion

This article is not intended to serve as a comprehensive review of Idaho’s procurement statutes. Rather, the primary purpose of the article is to emphasize that cities must adhere to high ethical standards when procuring goods, services, and public works construction. That is good government – and it is the law.

Kurt J. Starman is a Deputy City Attorney for the City of Meridian. Kurt has held several leadership positions in local government over the past 30 years – including 11 years as a city manager. He has encountered many challenging procurement issues.

[ii] Idaho Code § 74-403(10).

[iii] Idaho Code § 74-404.

[iv] Idaho Code § 74-404(4).

[v] Idaho Code § 74-404(5).

[vi] Idaho Code § 74-406(1) (“Any public official who intentionally fails to disclose a conflict of interest . . . shall be guilty of a civil offense, the penalty for which may be a fine not to exceed five hundred dollars . . . .”).

[vii] The Prohibition Against Contracts with Officers Act generally applies to “public officers,” but that term is not explicitly defined.

[viii] Idaho Code § 74-501.

[x] Idaho Code § 74-504.

[xi] Idaho Code § 74-508.

[xii] Idaho Code § 74-509.

[xiii] Idaho Code § 74-502(1).

[xiv] Id.

[xv] Idaho Code § 74-502(2).

[xvi] Id.

[xvii] Id.

[xviii] Idaho Code § 74-510 utilizes the term “public official,” instead of “public officer.”

[xix] Idaho Code § 74-510.

[xx] The Bribery and Corrupt Influence Act utilizes the term “public servant,” instead of “public official” or “public officer.” A public servant includes public officers, public employees, and certain consultants.

[xxi] Idaho Code § 18-1359(1)(d).

[xxiv] Idaho Code § 18-1307.

[xxv] Idaho Code § 59-1026.

[xxvii] Idaho Code § 54-1902(1).

[xxviii] Idaho Code § 54-1903(9).

[xxix] Idaho Code § 67-2310(1).

[xxx] Idaho Code § 67-2310(2).

[xxxi] Idaho Code § 54-1914(2).

[xxxii] Id.

[xxxiii] Idaho Code § 54-1920(2).

Attorneys for Civic Education Celebrates 10 Years of Service

Texie C. Montoya

Formed in 2013, Attorneys for Civic Education (“ACE”)[i] is proud to share with the members of the Bar the purpose behind its mission and several of its successes over the past 10 years of service to further civics education throughout Idaho. A work-group backed annually by the Idaho State Bar’s Government & Public Sector Lawyers Section and staffed by a group of attorney volunteers, ACE expresses its gratitude for the Section as well as the many generous donors that have supported its fundraising efforts to support the civics education programs for Idaho’s youth.

Origins and Vision

Ten years ago, the former Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor visited Boise for Idaho’s inaugural Women and Leadership Conference – hosted by Boise State University’s Andrus Center for Public Policy.[ii] During Justice O’Connor’s visit, she shared that “less than one-third of eighth-graders can identify the historical purpose of the Declaration of Independence,” adding that, “it’s right there in the name.”[iii]

That same year, ACE was created by Edith Pacillo, Jodi Nafzger, and Danielle Quade as their legacy project for the Idaho Academy of Leadership for Lawyers (“IALL”).[iv] IALL is a “highly selective and well-regarded leadership training program for lawyers from across the State of Idaho.”[v] “The mission of the Idaho Academy of Leadership for Lawyers is to promote diversity and inspire the development of leadership within the legal profession.”[vi]

The group formed ACE as their project because they recognized the critical importance of civics education in Idaho’s schools. In response to changes in federal funding for civics programs, ACE sought to increase participation by the Idaho State Bar in filling this important need. ACE recognizes that the key to a healthy, functioning democracy is a citizenry that is educated and knowledgeable about the United States Constitution, and the importance of the Rule of Law.[vii]

This common vision continues to unite ACE members: to increase and sustain the opportunities for civics education in Idaho’s schools in order to ensure that Idaho’s citizens will have a solid understanding of the Constitution, the Rule of Law, and our form of government. Through volunteering and fundraising for outreach and education, ACE is committed to supporting a quality civics education for all Idahoans, emphasizing youth activities. ACE is always looking for additional members that share this vision – join our monthly lunchtime meeting every second Thursday!

Unfortunately, due to a variety of factors, civics education can often take a backseat in schools to other subjects. Budgetary constraints have led to the programs supported by ACE suffering greatly reduced, or even completely diminished, funding. To help counter this, ACE holds an annual fundraising event called “Hilarity for Charity” – a night of comedy improv presented by its namesake troupe – that passes every dollar generously donated to support Idaho’s civic education programs. In 2022, this effort raised over $11,000 to directly support Idaho students.[viii]

Sobering Civics Statistics and How ACE Seeks to Address Them

Beginning with the 2016-2017 school year, Idaho joined a number of other states by requiring that high school students pass the U.S. citizenship exam before graduation.[ix] Some advocates for civics education claim that policies like these improve civics education, while critics claim requirements like this only create additional barriers.[x] While recent elections have seen increased engagement among youth,[xi] in the most recent assessment, less than a quarter of eighth-graders performed at or above the proficient level on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (“NAEP”) civics exam – with no improvement over the 2014 numbers and only slightly higher than a full decade earlier.[xii]

Once formed, ACE was brought under the umbrella of the Government & Public Sector Lawyers Section of the Idaho State Bar as a service project. Through the Section, ACE is able to avail itself of the resources of the Idaho State Bar and the Idaho Law Foundation to support its efforts. The Section provides the funding for ACE to sponsor its annual fundraiser – Hilarity for Charity – discussed previously.

ACE focuses on promoting civic education in Idaho and, specifically, on encouraging members of the Idaho State Bar to become involved in, and support, civic education programs. To be as effective as possible, and to avoid duplication of efforts, ACE is committed to working with, and supporting the efforts of other entities with similar projects including the Idaho Law Foundation’s Law Related Education Committee, the University of Idaho College of Law, and the Federal and State Courts.

Initially, ACE primarily engaged in recruiting volunteers and raising funds to benefit two civics education programs in Idaho: We The People and Project Citizen. Both are programs of the Center for Civic Education. Today, ACE also engages in raising and administering funds for other activities such as Continuing Legal Education (CLEs), student competitions, and content creation, and in helping obtain grant funding, providing grant administration support, and developing and presenting the programming for the Idaho Journalists’ Institute on Law-Related Civic Education and the Idaho Teachers’ Institute on Law-Related Civic Education.

Retrospective and Evolution of ACE’s Efforts

Let’s take a look back at how ACE went from those origins to the several activities it now helps.

We The People features a curriculum on the history and principles of the United States constitutional democratic republic. State programs conduct local teacher professional development, hold conferences, and organize local and state simulated congressional hearings for elementary and secondary students. ACE still supports We The People today.

Project Citizen is for middle and high school students. It engages students in monitoring and influencing public policy. Students work in groups to identify a public policy issue, research its causes, and propose solutions. Students document the results in a detailed written portfolio with visual aids.

ACE’s first fundraiser was a campaign called An Hour For Civics in 2015. Modeled after a similar program by the Indiana State Bar, the premise of the campaign was for every member of the Idaho State Bar to donate either an hour of their time to civics education or a dollar amount equal to their hourly billable rate. In 2016, ACE decided to add a little fun to the fundraising and shifted to “Hilarity for Charity.”

The Current Four Civics-Education Programs Supported by ACE

By 2015, ACE was also formally supporting Idaho Mock Trial which it continues to support today. Idaho Mock Trial is a program of the Idaho State Bar’s Law Related Education Committee.

Idaho Mock Trial includes a high school mock trial competition which teaches students in Grades 9-12 about the law and the legal system by participating in a simulated trial. Working with attorney and teacher coaches, participants prepare a hypothetical legal case and learn about our legal system while they develop important critical thinking, research, and presentation skills. Then, in real courtrooms, mock trial teams present their cases in front of a panel of judges and jury members (real judges and attorneys).

From opening statements through closing arguments, each team has its own attorneys and witnesses and must be prepared to try both sides of the case. The competition also includes a courtroom artist contest, to allow artistically talented students the opportunity to participate in the mock trial program. Artists observe trials and submit sketches that depict actual courtroom scenes. In addition to the high school competition, Idaho Mock Trial is working to expand the program to middle schools.

The third program that ACE supports is Youth in Government. Youth in Government is a program of the Idaho YMCA. YMCA Youth in Government is an in-depth educational program that teaches high school students how to be active citizens through a nine-month, interactive experience where they directly participate in the processes of the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of the Idaho State Government.

Students simulate and fulfill the roles and responsibilities of the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government. Youth in Government program participants are actively immersed in civil engagement through developing skills in properly writing bills, parliamentary procedure, moot court competitions, lobbying, and even electing official officers including the Governor, Chief Justice, Appellate Judges, and more.

As school and YMCA groups compete and hold workshops at local Regional Conventions, they work on preparing for the final State Convention held in Boise each year at the State Capitol Building. Youth participants can earn awards, scholarships, or even go on to participate nationally at the Conference of National Affairs representing all Idaho Youth in Government delegates.[xiii] Idaho has participated in Youth in Government for over 75 years.

Last year, ACE added a fourth program: Know Your Government (“KYG”). KYG is a national program of 4-H – a youth development program of the United States Department of Agriculture whose name stands for Head, Heart, Hands, and Health. The KYG program has a mission of empowering youth to be well-informed citizens who are actively engaged in their communities and the world.

ACE supports the University of Idaho Extension with the annual KYG Conference, which is held over President’s Day weekend in Boise while the legislature is in session. Student can attend judicial workshops, including participation in a mock trial and sentencing, or be assigned as legislators or lobbyists to work on bills and conduct a mock legislative session.[xiv]

Each project is warmly received by students and teachers alike. ACE volunteers enjoy participating in these events, students enjoy the unique learning opportunities, and teachers appreciate support to make learning fun.

Additional Efforts and Conclusion

ACE has grown in many other ways in recent years. Since 2018, ACE has supported the Institute for Secondary School Teachers and the Institute for Journalists. The Institute for Secondary School Teachers is targeted to teachers of government, history, and social studies. Their purpose is to enhance teachers’ understanding of the judicial branch of government at national and state levels and to motivate teachers to return to the classroom with new ideas and share that information with their students.[xv]

The Institute for Journalists is a partnership of ACE, the University of Idaho’s College of Law, and the Idaho Press Club. The institute focuses on journalists’ vital role in civic education, with emphasis on explaining the work of an independent, impartial judiciary and on illuminating the Rule of Law in media reports of court decisions.[xvi]

In its early years, ACE also helped host a Continuing Legal Education (“CLE”) course for Constitution Day with Concordia University Law School to satisfy its requirement to host programming for Constitution Day. Constitution Day is a federal observance that recognizes the adoption of the United States Constitution.

It is normally observed on September 17, the day in 1787 that delegates to the Constitutional Convention signed the document. A law establishing the present holiday was created in 2004 and mandates that all publicly funded educational institutions provide educational programming about the Constitution on that day. For the past two years, ACE has resurrected its Constitution Day CLE with panel discussions on the First Amendment. Like the previous two years, ACE will be providing a Constitution Day CLE in the Idaho State Capitol’s Lincoln Auditorium this September.

More recently, ACE has hosted a Civics Essay Competition for middle school students. In 2021 and 2022, dozens of students submitted essays and ACE awarded cash prizes to three winners and their schools each year. Generous support for the prizes has been provided by the Fourth District Bar Association.[xvii]

During the pandemic, ACE member Wendy Olsen identified the need for pre-recorded videos of instruction on the Law Related Education Committee’s Turning 18 in Idaho curriculum and a committee worked with University of Idaho law students to create a dozen short videos on the topics in the curriculum so that teachers and students could easily access them. Most recently, ACE has started a project to create other videos for Idaho teachers and students to easily access and learn about important civics topics such as the rule of law, Native American and tribal sovereignty and law, and the legislative process.

A Thank You

In the 10 years since ACE was created, The Advocate has featured at least 10 articles about the group, our history, and the programs we support. As we celebrate our 10th anniversary, I look forward to the next decade of We The People, Mock Trial, Youth in Government, Know Your Government, and a renewed interest in civics among our youth. I also hope that this milestone anniversary encourages bar members to help support this important foundation of our society.

Texie C. Montoya is an Associate General Counsel at Boise State University where she has worked for over 10 years. She is a past chair and current member of the Government & Public Sector Lawyers Section as well as a current co-chair of Attorneys for Civic Education.

[i] http://www.attorneysforciviceducation.org/.

[ii] https://oconnorlibrary.org/speeches-writings/women-and-leadership-boise-state-university.

[iii] Id.

[iv] https://isb.idaho.gov/wp-content/uploads/Legacy-Project-Master-List.pdf.

[v] https://isb.idaho.gov/member-services/programs-resources/iall/.

[vi] Id.

[vii] Don Burnett, Civic Education, the Rule of Law, and the Judiciary: “A Republic … If You Can Keep It”, 58 Advocate 26 (2015).

[viii] A list of 2023’s generous donors can be found on the ACE website: http://www.attorneysforciviceducation.org/news.html.

[ix] https://www.sde.idaho.gov/academic/civics/.

[x] https://www.americanprogress.org/article/state-civics-education/.

[xi] https://circle.tufts.edu/2022-election-center.

[xii] https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/civics/.

[xiii] https://www.ymcatvidaho.org/youth-in-government/.

[xiv] https://www.uidaho.edu/extension/4h/events/know-your-government.

[xv] https://www.uidaho.edu/law/outreach/teacher-ed.

[xvi] http://www.attorneysforciviceducation.org/institute-for-journalists.html.

[xvii] https://www.uidaho.edu/law/outreach/ace-civics.

Which Statute Applies? An Update on Attorney Fee Statutes in Government Entity Cases

Stephen L. Adams

There are many statutes that deal with attorney fees in cases involving governmental entities. Three examples include Idaho Code § 12-117, which awards attorney fees in any case involving, “as adverse parties a state agency or a political subdivision and a person,”[i] I.C. § 6-918A, which provides for attorney fees in tort claims act cases, and I.C. § 12-121, which provides for attorney fees wherever a case is “pursued or defended frivolously, unreasonably or without foundation.”[ii]

These three statutes are just a few of the attorney fee statutes or sources applying to governmental cases. However, there are many others, such as when a commercial transaction or employment claim is involved,[iii] when there is a constitutional issue in a case,[iv] when there is a public records act claim,[v] or when there is a public bidding challenge.[vi] Despite this, the three statutes identified previously will be the focus of this article.

At first blush, it seems that any or all of these statutes may apply to a case involving a governmental entity. However, Idaho case law is far from clear on this issue. This article discusses how these statutes operate, the Idaho Supreme Court’s repeated insistence that certain of these statutes are the exclusive source of attorney fees, the history of this exclusivity case law, and how to address it.

Application of Attorney Fee Statutes

Idaho Code §§ 12-117, 12-121, and 6-918A are fairly common attorney fee statutes that apply in lawsuits against governmental entities (outside of federal claims).[vii] They each apply in slightly different circumstances.

When a tort claim is brought against a governmental entity, the primary attorney fee statute is I.C. § 6-918A, which states, “[a]t the time and in the manner provided for fixing costs in civil actions, and at the discretion of the trial court, appropriate and reasonable attorney fees may be awarded to the claimant, the governmental entity or the employee of such governmental entity, as costs, in actions under this act, upon petition therefor and a showing, by clear and convincing evidence, that the party against whom or which such award is sought was guilty of bad faith in the commencement, conduct, maintenance or defense of the action.”[viii]

This language suggests a number of factors related to the application of this statute. First, it applies in tort act claims. Second, the award of attorney fees is discretionary, and not mandatory.[ix] However, this discretion appears to be intertwined with the third factor, which is that attorney fees may only be awarded under this statute if there is a finding by the trial court of bad faith by clear and convincing evidence. “The standard in section 6-918A is a high bar[.]”[x] “Bad faith is defined as dishonesty in belief or purpose.”[xi] Thus, the trial court may exercise its discretion to award attorney fees only after it has found a party acted in bad faith.

In contrast, I.C. § 12-117 has a more general application. “Unless otherwise provided by statute, in any proceeding involving as adverse parties a state agency or a political subdivision and a person, the state agency, political subdivision or the court hearing the proceeding, including on appeal, shall award the prevailing party reasonable attorney’s fees, witness fees and other reasonable expenses, if it finds that the nonprevailing party acted without a reasonable basis in fact or law.”[xii]

Based on this language, this statute applies to any case involving, as parties, agency/subdivision and a person, and is not based on the nature of the action. Unlike I.C. § 6-918A, it is mandatory, as it contains the word “shall.”[xiii] Thus, there is no discretion about whether fees are awarded under the statute. However, “I.C. § 12–117 requires a losing party to have acted frivolously or without foundation before fees may be awarded.”[xiv] The decision as to whether a party acted frivolously or without foundation appears to be discretionary.[xv]

Finally, under I.C. § 12-121, “In any civil action, the judge may award reasonable attorney’s fees to the prevailing party or parties when the judge finds that the case was brought, pursued or defended frivolously, unreasonably or without foundation.”[xvi]

This language applies to any civil case, regardless of the parties or the nature of the action. Unlike I.C. § 12-117, the award is discretionary. However, like I.C. § 12-117, that discretion is bound by the requirement that the case be brought or defended frivolously or without foundation. Without going into the plethora of cases that explain this language, a simple way of looking at this statute is, “Where questions of law are raised, attorney fees should be awarded under I.C. § 12–121 only if the nonprevailing party advocates a plainly fallacious, and, therefore, not fairly debatable, position.”[xvii] Stated another way, “When deciding whether attorney fees should be awarded under [§] 12-121, the entire course of the litigation must be taken into account and if there is at least one legitimate issue presented, attorney fees may not be awarded even though the losing party has asserted other factual or legal claims that are frivolous, unreasonable, or without foundation.”[xviii]

As with all attorney fee situations, the availability of attorney fee awards is taken from the perspective of the American Rule, “which requires a party requesting attorney fees on appeal to cite either statutory or contractual authority in support.”[xix] As a result, awards of attorney fees are often a matter of statutory interpretation.[xx] In other words, attorney fees are not a matter of right in Idaho and should be hard to get.

Attorney fees may be exclusively available under only one statute

Even if attorney fees should be hard to get, the situation need not be as confusing as it is. Idaho’s appellate courts have not made it easy to figure out which statute parties may rely on. In a 2013 article about this exact same issue, it was pointed out that Idaho case law is extremely confusing as to whether any particular attorney fee statute is exclusive in a given situation.[xxi] The article noted numerous cases between 1996 and 2013 holding that I.C.§ 6-918A was exclusive where it applied, and numerous cases holding that I.C. § 12-117 was exclusive where it applied.[xxii] During the same time period, there were at least eight other cases involving governmental entities where the exclusivity of these statutes was not noted, and fees were awarded under other statutes.[xxiii] Consequently, it was difficult to know which fee statute applied when a governmental entity was involved in a lawsuit.

The situation has not gotten any clearer since then. In 2013, the Supreme Court seemed to make some headway as to the whether attorney fee statutes are exclusive when a governmental entity is involved, stating in Syringa Networks, “we hold that section 12–117(1) is not the exclusive basis upon which to seek an award of attorney fees against a state agency or political subdivision, but attorney fees may be awarded under any other statute that expressly applies to a state agency or political subdivision, such as sections 12–120(3) and 12–121.”[xxiv] This language was upheld a year later in an April 2014 opinion.[xxv]

However, in a June 2014 opinion, the Supreme Court went into detail about the exclusivity between I.C. §§ 12-117 and 6-918A, and held that 6-918A is exclusive where it applies.[xxvi] The Supreme Court followed this up with two 2020 opinions further confusing this matter, holding that “section 12-121 is not applicable because section 12-117 is the exclusive means for awarding attorney fees for the entities to which it applies.”[xxvii] Thus, if there ever was clarity on the issue of exclusivity, it has sunk again into a quagmire of conflicting opinions.

A brief history of statutory exclusivity

As discussed, attorney fees are only available if there is a statute that provides for them. Thus, application of attorney fee statutes should turn on interpretation of the statutory language. In looking at these three statutes, the only one of them that utilizes the word “exclusive” in any form is I.C. § 6-918A, which states, “[t]he right to recover attorney fees in legal actions for money damages that come within the purview of this act shall be governed exclusively by the provisions of this act and not by any other statute or rule of court, except as may be hereafter expressly and specifically provided or authorized by duly enacted statute of the state of Idaho.”[xxviii] Neither I.C. § 12-117 or 12-121 mention exclusivity. Therefore, how and why have courts interpreted these statutes as exclusive?

As far as the author can tell, the first case discussing exclusivity of fees is Camp v. Jiminez, a 1984 case in which the Idaho Court of Appeals noted that I.C. § 12-121 was not exclusive of other potentially applicable statutes.[xxix] The Court utilized similar language in 1988 when it found that I.C. § 32-704(2) was not the exclusive source of attorney fees in a divorce action, and that “I.C. § 12–121 applies to all civil actions.”[xxx] In other words, neither of these two cases held that a fee statute was exclusive.

The first case where a fee statute was held to be exclusive was the 1989 case Kent v. Pence, where the Court of Appeals noted that I.C. § 6-918A was exclusive as to cases involving the Tort Claims Act.[xxxi] This analysis was based on the language of § 6-918A which, as noted previously, states that the statute is exclusive. Kent, oddly, relies on language from Packard v. Joint Sch. Dist. No. 171, a 1983 case which does not discuss exclusivity, and even analyzes both §§ 6-918A and 12-121.[xxxii] Regardless, Kent appears to be the first case discussing statutory exclusivity.

After Kent, in Tomich v. City of Pocatello, the Idaho Supreme Court again discussed exclusivity of § 6-918A over § 12-121, noting that § 6-918A is both the later and more specific statute, and therefore it applies when there is a conflict.[xxxiii] In applying these canons of construction, the Supreme Court did not actually state that a conflict occurred; it merely decided to apply § 6-918A as the relevant fee statute.

The exclusivity issue appears to have jumped to I.C. § 12-117, like a contagious disease, for the first time in 1996. In Roe v. Harris, the Idaho Supreme Court discussed the “interplay between I.C. § 12–117 and the private attorney general doctrine.”[xxxiv] After substantial discussion about prior caselaw discussing exclusivity, the Supreme Court again turned to the canon of construction that new and more specific statutes control when there is a conflict.[xxxv] In doing so, the Court found a conflict in the language of § 12-117 and the attorney general doctrine (which it compared to I.C. § 12-121) because the two statutes were different in how attorney fees were awarded (“the private attorney general doctrine considers the value of the prevailing party’s contribution, while I.C. § 12–117 considers the character of the losing party’s case.”).[xxxvi] However, they did not note that the actual language of § 12-117 and 12-121 conflicted; only that they were different.

This brings us to State v. Hagerman Water Right Owners, Inc. (HWRO), a 1997 case which appears to be the genesis of most exclusivity language in later cases discussing attorney fee statutes. In that case, it simply says, “I.C. § 12–117 provides the exclusive basis of an award of attorney fees against a state agency.”[xxxvii] Hagerman relies on Roe v. Harris for this analysis and does not include any discussion of conflict between statutes.

There is no need for attorney fee statutes to be exclusive

Neither the statutory language nor the historical case law justifies the rampant and confusing rulings discussing exclusivity of attorney fee statutes in governmental entity cases. Exclusivity with regards to I.C. § 6-918A makes sense, as the statute clearly says that it is exclusive where it applies. However, neither I.C. § 12-121 nor § 12-117 contain language mandating exclusivity. To the extent that exclusivity has arisen out of the context of a “conflict” between statutes, only Roe discusses a conflict, and that conflict is based on a statute (§ 12-117) and a common law attorney fee doctrine. There was no actual statutory language discussed which was shown to conflict.

In reviewing these three attorney fee statutes, they do not conflict; instead, they all do the same thing, but in different ways. As noted, awards under I.C. § 12-117 are mandatory where they apply, whereas awards under I.C. § 12-121 are discretionary. However, both require a similar analysis as to the level of conduct necessary to support an award. There is nothing in either statute that suggests the legislature intended one to apply over the other. Indeed, I.C. § 12-117 begins with, “[u]nless otherwise provided by statute,”[xxxviii] which suggests that it may be intended to give way to other statutes. Regardless, there is nothing in these two statutes that indicates a judge cannot analyze both separately to determine whether attorney fees are available under both, either, or neither.

Frankly, the entire discussion of exclusivity of attorney fee statutes appears to be based on a misapplication of Roe. Roe, in turn, seems to misapply the “later in time” and “more specific” canons of construction. These canons only apply if statutes cannot be reconciled.[xxxix] Roe provided no explanation of the conflict and does not appear to have attempted to reconcile the two statutes. Based on their plain language, I.C. § 12-117 and I.C. § 12-121 could both be applied to a given case, and one or both may allow for an award of fees. Nothing about this constitutes a conflict. Further, to the extent that Hagerman (and ostensibly Roe) was abrogated by Syringa Networks,[xl] there is no reason why the Supreme Court shortly jumped back to interpreting attorney fee statutes as exclusive without mentioning Syringa. As a result, there appears to be directly conflicting case law, without any logical reason as to why the conflict exists.

Possible steps to ask for attorney fees

Realistically, clearing up this matter is in the hands of Idaho’s appellate courts or the legislature. However, as a practical matter, when it is impossible to determine which statute is the exclusive attorney fee statute, or whether there is even an exclusive attorney fee statute, a practitioner should make arguments under every potentially applicable statute. As demonstrated, the legal standards to various statutes are not identical, but they are similar enough that making multiple arguments should not create substantial extra work. Then, because it is unclear which statute may apply, the practitioner should ask the court for findings under each potential statute. This way, even if the matter is appealed, the trial court will have addressed all potential statutes, and the matter is less likely to be remanded for additional findings. In other words, until the Supreme Court clears this issue up, a shotgun approach, which is not usually the best approach for an argument, may be ideal.

Stephen L. Adams is an attorney with Gjording Fouser, PLLC in Boise. He is a member of the Government & Public Sector Lawyers Section and is on the boards of the Appellate Practice Section and the Idaho Association of Defense Counsel. He also is happily married to a lovely wife and has four kids. He has defended school districts, hospitals, cities, insurance companies, and lots and lots of individuals. Needless to say, he’s tired all the time.

[i] Idaho Code § 12-117(1).

[ii] Idaho Code. § 12-121.

[iii] See Idaho Code § 12-120(3).

[iv] See 42 U.S.C. § 1988.

[v] See Idaho Code § 74-116.

[vi] See Idaho Code § 67-2809(2)(e).

[vii] Though, as discussed, there are many other statutes that apply to specific circumstances.

[viii] Idaho Code § 6-918A.

[ix] “This Court has interpreted the meaning of the word ‘may’ appearing in legislation, as having the meaning or expressing the right to exercise discretion.” Rife v. Long, 127 Idaho 841, 848, 908 P.2d 143, 150 (1995).

[x] Hollingsworth v. Thompson, 168 Idaho 13, 24, 478 P.3d 312, 323 (2020).

[xi] Renzo v. Idaho State Dep’t of Agr., 149 Idaho 777, 781, 241 P.3d 950, 954 (2010).

[xii] I.C. § 12-117(1).

[xiii] Rife, 127 Idaho at 848, 908 P.2d at 150. See also Univ. of Utah Hosp. v. Ada Cnty. Bd. of Comm’rs, 143 Idaho 808, 812, 153 P.3d 1154, 1158 (2007) (“The statute is mandatory and we will award attorney fees to the providers if the County did not act with a reasonable basis in fact or law.”).

[xiv] City of Osburn v. Randel, 152 Idaho 906, 910, 277 P.3d 353, 357 (2012).

[xv] Id.

[xvi] I.C. § 12-121.

[xvii] Lowery v. Bd. of Cnty. Comm’rs for Ada Cnty., 115 Idaho 64, 69, 764 P.2d 431, 436 (Ct. App. 1988).

[xviii] Robirds v. Robirds, 169 Idaho 596, 611, 499 P.3d 431, 446 (2021).

[xix] Mortensen v. Stewart Title Guar. Co., 149 Idaho 437, 447–48, 235 P.3d 387, 397–98 (2010).

[xx] Med. Recovery Servs., LLC v. Lopez, 163 Idaho 281, 282–83, 411 P.3d 1182, 1183–84 (2018) (“However, when an award of attorney fees depends on the interpretation of a statute, the standard of review for statutory interpretation applies.”).

[xxi] Stephen Adams, “An Update on Attorney Fees in Cases Involving Governmental Entities”, 56 Advocate 60, 60–61 (2013).

[xxii] Id. at 61 (n. 15).

[xxiii] Id. at 61 (n. 16).

[xxiv] Syringa Networks, LLC v. Idaho Dep’t of Admin., 155 Idaho 55, 67, 305 P.3d 499, 511 (2013)..

[xxv] See Sanders v. Bd. of Trustees of Mountain Home Sch. Dist. No. 193, 156 Idaho 269, 272–73, 322 P.3d 1002, 1005–06 (2014) (relying on Syring Networks to award attorney fees under Idaho Code § 12-120(3)).

[xxvi] Block v. City of Lewiston, 156 Idaho 484, 490, 328 P.3d 464, 470 (2014).

[xxvii] Dep’t of Env’t Quality v. Gibson, 166 Idaho 424, 447, 461 P.3d 706, 729 (2020), reh’g denied (May 7, 2020). See also Lingnaw v. Lumpkin, 167 Idaho 600, 609–10, 474 P.3d 274, 283–84 (2020) (discussing exclusivity of §§ 12-117 and 12-121).

[xxviii] I.C. § 6-918A.

[xxix] Camp v. Jiminez, 107 Idaho 878, 884, 693 P.2d 1080, 1086 (Ct. App. 1984).

[xxx] Hentges v. Hentges, 115 Idaho 192, 197, 765 P.2d 1094, 1099 (Ct. App. 1988).

[xxxi] Kent v. Pence, 116 Idaho 22, 22–23, 773 P.2d 290, 290–91 (Ct. App. 1989).

[xxxii] Packard v. Joint Sch. Dist. No. 171, 104 Idaho 604, 614, 661 P.2d 770, 780 (Ct. App. 1983).

[xxxiii] Tomich v. City of Pocatello, 127 Idaho 394, 400, 901 P.2d 501, 507 (1995).

[xxxiv] Roe v. Harris, 128 Idaho 569, 572, 917 P.2d 403, 406 (1996), abrogated by Rincover v. State, Dep’t of Fin., Sec. Bureau, 132 Idaho 547, 976 P.2d 473 (1999).

[xxxv] Id. at 572–73, 917 P.2d at 406–07.

[xxxvi] Id. at 573, 917 P.2d at 407.

[xxxvii] State v. Hagerman Water Right Owners, Inc. (HWRO), 130 Idaho 718, 726, 947 P.2d 391, 399 (1997), abrogated by Syringa Networks, LLC,155 Idaho 55, 305 P.3d 499.

[xxxviii] I.C. § 12-117(1).

[xxxix] Hyde v. Fisher, 143 Idaho 782, 786, 152 P.3d 653, 657 (Ct. App. 2007). See also 73 Am. Jur. 2d Statutes § 161.

[xl] Syringa Networks, LLC,155 Idaho at 67, 305 P.3d at 511.

Public Service Attorneys in Idaho: Insights and Perspectives Working in Public Service

Rachel L. Kolts

I was inspired to pursue a career in public service from a young age thanks in large part to my parents, who have each enjoyed life-long careers in public service. My career as a public service attorney has been and continues to be, incredibly rewarding and fulfilling. I often speak about the many positives of pursuing a career in public service and recommend it to anyone who expresses an interest in it.

I reached out to a handful of public service attorneys throughout the state, ranging from the city level to the federal level, each with unique career paths, and asked them to share their insights and perspectives on working in public service. Here is what they graciously shared with me.

Mia Bautista

Mia Bautista worked in the Latah County Prosecutor’s Office from the second semester of her 2L year up to graduation, where she gained a significant amount of hands-on experience handling the prosecution of cases. She then accepted a position with the Nez Perce County Prosecutor’s Office where she worked as a Deputy Prosecutor for 10 years. Wanting to work in the same town she was residing in, Mia accepted a position with the Latah County Prosecutor’s Office in Moscow and held the roles of Deputy Prosecutor and Senior Deputy Prosecutor. Six years later, she was appointed to the position of City Attorney for Moscow in 2018 and has held that position since. Mia is the first woman to be appointed as the City Attorney for Moscow.

Q: What inspired you to pursue a career in public service?

A: My life experiences from my earliest memories of childhood through to high school are what drove me to want to have a career in public service, a career where I could make a difference in people’s lives and positively contribute to society for the greater good. I often think of the quote from Martin Luther King, where he said, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.” This quote captures my motivation to continue in public service.

Q: What do you like most about being a public service attorney?

A: Early in my career I liked being a voice for not only the state’s interest in the way in which I prosecuted cases, but for the victims and children impacted by crimes. I liked being a part of a solution to help people who in a weak moment made a bad decision, and then tried to find a solution that addressed the root issues and one that would help not only the person who committed the crime, but those who were impacted by the crime. As I have transitioned out of prosecution work and now work as the legal advisor to the City and its representatives, I enjoy providing a broader level of support and guidance to those who make decisions for the City with the public’s best interest in the forefront of their decision making.

Q: What has surprised you about being a public service attorney?

A: There are many nuances to the law, both civil and criminal, where there always seems to be a situation where it’s a “first impression” issue. I’m constantly learning.

Q: What motivates you to remain in public service?

A: The same motivation that drove me to a career in law.

Q: What recommendation or piece of advice do you have for attorneys who may be considering switching to a career in public service?

A: If your motivation for work is simply based on the amount of money in your paycheck, public service is not for you. If you want to be able to go home at night and know that you played a role in bettering your community, then public service is the type of career you should pursue.

Terry Derden

Terry Derden’s original goal was to work for the FBI, but after his first summer internship with the Boise City Prosecutor’s Office, he was completely sold on being a prosecutor. Following graduation, he worked as a prosecutor and Deputy City Attorney with the City of Boise for 12 years. Thereafter, he was offered a job with the Ada County Sheriff’s Office as their Chief Legal Advisor (the Chief Legal Advisor is a member of the Sheriff’s Executive Staff and essentially acts as in-house counsel for the Sheriff of Ada County). Terry will be starting his seventh year as counsel for the Sheriff in June 2023.

Q: What inspired you to pursue a career in public service?

A: Both of my parents were public service attorneys. My mother worked as a deputy attorney general in the appellate division, before moving to be the staff attorney for the Idaho Supreme Court for more than 20 years. My father served as an Assistant United States Attorney for his entire career, retiring as the Criminal Chief in Idaho after 32 years. Through them I was able to meet so many people in public service as prosecutors, defense attorneys, police officers, federal agents that I knew that I wanted to help keep my community safe and work in public service.

Q: What do you like most about being a public service attorney?

A: My favorite thing about being the in-house counsel for the Sheriff these last 7 years has been the variety of what I get to work on day to day. Instead of “Chief Legal Advisor” my title should be “Problem Solver Du Jour.” The variety and scope of what I am asked to work on was also why I loved being a deputy city attorney. Every government entity gets presented unique problems on a regular basis and it is up to “the attorney” to go understand the problem and find a solution for the client. As opposed to private counsel who usually develop a specialty over the years, I feel like my practice areas broaden every year as we deal with new problems and situations.

Before taking this job, I had never once researched RLUIPA nor ever thought about whether an inmate in jail has a religious right to possess a marijuana plant as part of his religious beliefs (in that one, he was satisfied praying to a drawing of one once we told him he can’t have contraband in the jail) nor did I have ever consider how to legally create an agreement between two county sheriffs so a contract city police department can operate in two different counties at the same time (which was needed once Star, Idaho annexed land into Canyon County so that their city police could have jurisdiction to operate in both Ada and Canyon). Those are the kind of big and small problems I get assigned every day because the Sheriff has a problem and now needs a solution.

Q: What has surprised you about being a public service attorney?

A: The people I have been able to meet and the places I have gotten to go because of this job has been the most surprising. I did not have big plans to become a national speaker or trainer, but as I developed my specialty in the law surrounding “use of force” for police, I have been invited to train or teach all over the country. I have found delivering a keynote to a big audience or doing a two to three hour training with a group of police officers who are hungry to learn how they can be better is a similar feeling to being in a big trial where you have to rely on your knowledge and your persona to get your points across and move the needle in the right direction. It is extremely satisfying in this day and age when I realize that I have an entire room full of people actually engaged in what is being talked about (and not just looking at their phones) because they are finding value in what I am presenting and can use it to be better at their jobs, avoid liability, and keep their communities safer. My hope is that the effort I am making to get that room full of cops to think about how they apply force to a suspect may mean they avoid an excessive use of force incident, avoid injuring someone, avoid a federal lawsuit, but also keep themselves safe so they can go home to their family when their shift is over.

Q: What motivates you to remain in public service?

A: My parents told me (and demonstrated) that I should live a life of service to others and give back to this world in some way to repay what I was given in terms of my life and my opportunities. While I am now teaching my sons to have that same philosophy on life regardless of the career they choose, I also realize that I was very lucky to have been raised in a place like Boise. I am very thankful that I got the chance to go to law school and I am very grateful that I can do this work as Chief Legal Advisor to assist the Sheriff in making policy decisions and political decisions that really affect change for the community. I have a strong sense that my work here helps the Sheriff and deputies here in Ada County provide a safe place for the citizens to live, work, and play. I am happy to do my part to make sure other families feel as lucky to live here as I do with my wife and sons.

Q: What recommendation or piece of advice do you have for attorneys who may be considering switching to a career in public service?