Month: November 2023

Immigration and the Best Interests of Children

by Rees G. Atkins

U.S. immigration law disregards the best interests of children, which conflicts with Idaho’s (and other states’) centuries-old family law principles. Family law principles, such as frequent contact with both parents and stability, show long-valued benefits that are worth protecting for children.[i] Immigration law gives jarringly little attention to those benefits, and could still achieve its immigration-related goals while protecting children’s needs. This article will review Idaho’s principles of family law, compare them with federal principles, and offer suggestions for reconciliation and coordination between the two legal regimes.

Idaho Family Law Principles

In Idaho, and every other state in the United States,[ii] the guiding principle for custody determinations is to examine the “best interests” of the child.[iii] Furthermore, in Idaho there is “a presumption that joint custody is in the best interests of a minor child or children.”[iv] Joint custody is defined as “an order awarding custody of the minor child or children to both parents and providing that physical custody shall be shared by the parents in such a way as to assure the child or children of frequent and continuing contact with both parents.”[v] The only way to trigger the opposite presumption is for one of the parents to be a habitual domestic violence perpetrator.[vi]

As important as frequent and continuing contact with both parents is, perhaps even more important is stability.[vii] Judges are unlikely to order a custody arrangement that requires frequent travel, separation of siblings, or uprooting the children to a new primary location. Statutory factors judges consider when determining a custody schedule include the “child’s adjustment to his or her home, school, and community” and the “need to promote continuity and stability in the life of the child.”[viii]

The Idaho Supreme Court has found that “a presumption that it is in a child’s best interest to relocate with the custodial parent . . . is contrary to Idaho law, which requires the moving parent to prove that relocation is in the child’s best interest.”[ix] In one case, it upheld a trial judge’s decision to give “primary physical custody” of a child to the mother “as long as she remains in Idaho.”[x] The fact that the mother’s new husband, a U.S. Army officer, had been transferred to Hawaii was not sufficient to outweigh the child’s interest in staying in the geographical area where she had been growing up.[xi]

While it is theoretically possible for parents to live a great distance apart and still accomplish frequent and continuing contact with the child, stability warrants courts favoring both parents living in the general area where the child has been growing up.

With these two basic and common-sense principles in mind, that children need 1) frequent and continuing contact with both parents and 2) stability, let’s examine immigration law.

Federal Deportation Proceedings

8 U.S.C. § 1227 provides dozens of grounds that make a noncitizen deportable, the most common being unlawful presence – living in the United States without permission from the United States government. Most in this situation have been here unlawfully for more than a year, which subjects them to needing to leave the United States for 10 years before obtaining a visa to come as a lawful permanent resident.[xii] However, that eventual return is generally only possible for those who have a citizen or lawful permanent resident family member who can petition for a visa for them, and a child born here (and who is therefore a citizen) cannot petition for a parent until the child is 21 years old.[xiii] The Pew Research Center found in 2018 that “[c]hildren of unauthorized immigrant parents constituted nearly 8% of students in kindergarten through 12th grade in 2016. Of those 4.1 million children, 3.5 million are U.S. citizens and the rest are unauthorized immigrants themselves.”[xiv] Accordingly, there are millions of U.S. citizen children with parents who are deportable noncitizens and who, without exceptional circumstances, would have to wait in another country for at least 10 years prior to returning legally if they are deported or leave voluntarily. In simplest terms, potential deportation puts many families in precarious positions.

There is a defense to deportation called cancellation of removal, but it is almost impossible to prevail. A noncitizen is only eligible if he or she has been in the United States for 10 years, has had good moral character during those 10 years (which includes avoiding certain convictions), and deportation would cause “exceptional and extremely unusual hardship” on the noncitizen’s citizen or lawful permanent resident spouse, parent, or child.[xv] Furthermore, hardship to the noncitizen facing deportation proceedings or any family members who are here unlawfully is not considered at all, no matter how extreme.[xvi]

Interpreting this standard, the Board of Immigration Appeals (“BIA”) overturned an immigration judge’s grant of relief to a noncitizen mother who had been in the United States for more than 10 years with good moral character, finding that hardship to her six and 11-year-old U.S. citizen children did not meet the high statutory standard of being both “exceptional and extremely unusual.”[xvii] It found there would be hardship, but only ordinary hardship involved in deportation proceedings.[xviii] While I would not defend the BIA’s decision while advocating for a specific client, I can’t say I blame the BIA for finding that it is not “exceptional and extremely unusual” for children to be devastatingly harmed by either 1) separation from their mother; or 2) accompanying their banished mother to a country they have never been to and which is much more dangerous than the United States. In fact, I would say it would be only the exceptional and extremely unusual case where there is not immense hardship inflicted on the child.

As stated by the BIA in that case, “virtually all cases involving respondents from developing countries who have young United States citizen or lawful permanent resident children” involve importantly damaged futures for those children, and a standard requiring “exceptional and extremely unusual” circumstances is set up to give relief to only a small portion of them.[xix] Essentially, it found that congressional intent was such that the courts’ standard must result in separation or relocation of U.S. citizen children in most of the proceedings with an unlawfully present or otherwise deportable parent, because the inherent nature of the words “exceptional and extremely unusual” implies application to a minority of cases.

Therefore, Idaho’s attempt to protect 1) frequent and continuing contact with both parents; and 2) stability, is derailed by our immigration law for most of the children of these immigrants. If parents are divorced, the children are likely to stay in the United States with the parent who is not deported and be deprived of frequent and continuing contact with the deported parent. If the parents are together, family unity can only be obtained if the entire family uproots to another country.[xx]

The Peril of a Parent Undocumented in the United States

Of course, deportation proceedings are rarely initiated for noncitizens who do not have repeated or serious criminal violations, which is why there are millions of undocumented immigrants in the United States. But lack of deportation does not change undocumented immigrants’ status as less-than-second-class citizens. In most states, they cannot obtain a driver’s license.[xxi] In all states, they cannot vote, serve on juries, visit their home country, or even work legally.

The inability to work legally presents an interesting question regarding child support. Child support is ordered in accordance with detailed child support guidelines, and the guidelines are usually followed meticulously.[xxii] The amount ordered is based mostly on parents’ income and the number of children supported.[xxiii] For a noncitizen here illegally, does the judge use the actual income (earned through unlawful employment) of the parent to calculate child support?[xxiv] If so, the judge would be ordering an amount of child support that is illegal to earn in the United States and totally impossible for the parent to earn in their home country of, say, Nicaragua, where the average yearly income is $1,695, compared to $59,034 in the United States.[xxv]

Child support obligations can be enforced through civil contempt proceedings under Idaho Rule of Civil Procedure 75, which requires that the contempt is willful. So, for example, child support obligations are routinely suspended while a parent is incarcerated, because the parent is incapable of earning income. A failure to pay an unachievable amount of child support would not be willful, and hence enforcement would not be allowed.

And what does a good parent do in this situation? Imagine a parent in divorce proceedings who says to the judge:

Your honor, although I am a very successful businessman here, I have actually been here illegally for twenty years. I wanted a better future than I thought would be possible in my home country where there is more poverty and violence. But I recognize now that I needed to pursue that goal through lawful means. So, to be an example of a law-abiding citizen (or law-abiding person anyway) for my children, I am going to leave my children here with their mother and return to my home country. I already have a job lined up with my uncle there that is better than most jobs there, but unfortunately, I will make about one thirtieth of what I make here, so under the child support guidelines, I will need the amount ordered to be reduced. But don’t worry, I have already begun helping the mother of my children prepare to apply for and move into federally subsidized housing, so they won’t be homeless.

Would a judge ever believe that parent was being sincere? Unlikely, but if so, that is horrible for those children (and our subsidized housing budget). If not, what does a sincerely repentant parent do and speak? If the answer is that he chooses to not abandon his children and remain in the United States unlawfully, then our immigration law is inequitable and immoral, forcing the undocumented person to remain illegal as a condition of staying with his family. If complying with the law is immoral, then the law loses respect and credibility. Federal enforcement of such immorality is costly and counterproductive to undocumented families, to the U.S. government, and to the American taxpayers.

Suggestions for Reconciling the State-Federal Familial Disconnect

For too long, basic family stability for children has been relegated far below other priorities, such as avoiding forgiveness of a past law violation. Set forth below are some ideas that could assist in carefully balancing our state’s preference for keeping families whole with the federal efforts addressing immigration enforcement. Any solution, as offered thus far, appears imperfect—which serves to highlight the complexity of the contradiction between state and federal preferences.

If the idea of withholding legal status (and occasionally deporting) is to deter more people from coming illegally, such deterrence is likely ineffective. Customs and Border Protection reports hundreds of people dying each year as they attempt to cross the southern border (often due to desert conditions).[xxvi] With that danger (plus the risk of civil and criminal fines and imprisonment for illegal entry under 8 U.S.C. § 1325), the fear of a distant future deportation and continually withheld legal status must be given relatively little weight in immigrants’ minds as they decide whether to come.

One solution could be to use some of the revenue of increased tax compliance that would result from legalization to fund surveillance and/or a barrier.[xxvii] And rather than the unpredictability that would arise with occasional enforcement and occasional benefits based on a specific date, such as the legalization act in 1986, a US statutory provision or constitutional amendment preventing deportations for past and future immigrants who have been present for over a year would motivate enforcement at the border and prevent uprooting families. Where true wrongs have been done, traditional criminal penalties could be used.

Unfortunately, it seems both sides of the issue are adamantly opposed to giving any advances to the other side, with unthinking resistance to anything that can be compared to “amnesty” on one side or a “wall” on the other. But if enough people put their minds to it, new and less incendiary ideas may arise. The best ideas will come by viewing the situations of undocumented families compassionately and honestly, in conjunction with the analysis of what is happening at the border, the need for order, and international pressures. Until we help our representatives to act, the anxiety and risk faced by these millions of children will continue to be treated as a minor factor in our immigration policy.

The children we see in our state courts, schools, and neighborhoods are people, regardless of how their parents came here. We have a responsibility to do our best to protect them from life-altering harm, especially harm from our own laws. Idaho law has an overarching preference for the maintenance of families, but Congress thus far has not agreed. We can protect them through statutory amendments. Or, if for some reason Congress continues to talk about the need for reform but without reforming, through constitutional amendment by the states.[xxviii]

Rees G. Atkins

Rees G. Atkins works for the Mini-Cassia Public Defender’s Office. He previously practiced immigration law at Echelon Law and has represented parents in custody proceedings. He began his legal career as a law clerk to the Honorable Benjamin J. Cluff of Idaho's Fifth Judicial District. Rees's highest priority is his family. He hopes that immigrants can also have the benefits of peaceful family life that he enjoys.

[i] The basic argument in this article is that [frequent contact with both parents and stability are important needs of children] implies [immigration law should better account for those needs]. Rather than discussing family law, a more standard/scientific method to show my premise might be studies showing the benefits/harms to children with/without frequent contact with both parents and stability. However, studies have their own set of limitations, and the long-accepted family law principles may show the premise does not need such proof.

[ii] For a history of this standard, see Janet L. Dolgin, Why Has the Best Interest Standard Survived?: The Historic and Social Context, 16 Child. Legal Rts. J. 2 (1996), available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/faculty_scholarship/433.

[iii] I.C. 32-717.

[iv] I.C. 32-717B(4).

[v] I.C. 32-717(1).

[vi] See I.C. 32-717(5).

[vii] The especially high importance of stability is relevant to this article because, no matter what the relationship between parents might be, stability is always harmed when immigration laws do not recognize the basic needs of the children of undocumented children.

[viii] I.C. 32-717.

[ix] Bartosz v. Jones, 146 Idaho 449, 455 (Idaho 2008).

[x] Id. at 452.

[xi] Id. at 455.

[xii] 8 U.S.C. § 1182(a)(9)(B).

[xiii] 8 U.S.C. § 1151(b)(2).

[xiv] https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2018/11/27/most-unauthorized-immigrants-live-with-family-members/.

[xv] 8 U.S.C. § 1229b.

[xvi] There are also claims that can be made for asylum or for relief under the Convention Against Torture, but those are also difficult to succeed with (for example, just 15% success for Mexicans). See https://trac.syr.edu/immigration/reports/668/. Chances for long-established families are even slimmer, because asylum claims ordinarily must be made within one year of entering the United States, and because memories and connections with the home country that are necessary to prove an asylum or asylum-like claim will dissipate over time. 8 U.S.C. 1158.

[xvii] Matter of Andazola, 23 I&N Dec. 319 (BIA 2002).

[xviii] Id.

[xix] Id. at footnote 1.

[xx] Families are frequently separated, often for only short periods, by one parent being incarcerated. But this differs significantly from immigration cases in that some mens rea must be proven in criminal cases, and a criminal defendant enjoys the immense constitutional protections which, in addition to preventing error, give bargaining power to the criminal defendant so that an unnecessarily harsh result is less likely. And, tragically, sentencing judges may be doing children a favor by putting a drug-abusing or otherwise criminal parent in jail.

[xxi] https://www.ncsl.org/immigration/states-offering-drivers-licenses-to-immigrants.

[xxii] See Idaho Rules of Family Law Procedure 120.

[xxiii] Id.

[xxiv] It may be that family law cases with undocumented immigrants rarely come before the courts, due to a fear by all parties that court involvement will increase the chances that immigration authorities will become involved. This fear-based lack of access to courts and law enforcement has been addressed in the criminal arena by giving some limited immigration benefits to certain victims of crimes, but comparable benefits do not exist for people seeking court help in family law disputes.

[xxv] https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.ADJ.NNTY.PC.CD.

[xxvi] https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/border-rescues-and-mortality-data.

[xxvii] It is estimated that income tax compliance for undocumented immigrants is between 50 and 75 percent, whereas ordinary wage income compliance is nearly perfect for others. See https://www.whitehouse.gov/cea/written-materials/2021/09/17/the-economic-benefits-of-extending-permanent-legal-status-to-unauthorized-immigrants/.

[xxviii] Some evidence that states may come together in favor of more liberal immigration policies is the broad acceptance of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) and lack of enforcement of work authorization. Only two states, Arizona and Nebraska, gave any substantial resistance to giving driver’s licenses to DACA recipients, and only Arizona had to be forced to give them by anti-discrimination litigation. See https://www.nilc.org/issues/drivers-licenses/daca-and-drivers-licenses/. Only nine states are part of the current lawsuit against DACA, despite the salient questions regarding DACA’s constitutionality.

Child Representation: The Value of Being Seen, Heard, and Represented

by Jessalyn R. Hopkin and Stacy L. Pittman

In child protection cases, children are the focus. When a child suffers from neglect or abuse, the state can step in to protect the child. From shelter care, to case planning, to case closure, the court must examine the best interest of the child. Unfortunately, what is frequently overlooked in child protection cases, is the child. Though the case itself is about the child’s best interest, in many court rooms across Idaho, children do not have a voice to opine what they believe is in their best interest. The same children who are meant to be protected in cases of neglect or harm deserve to have counsel with the same duties of undivided loyalty, confidentiality, and competent representation as is due to adult clients.

A 2018 report conducted by the Idaho Office of Performance Evaluations (“OPE”) found that anywhere between 19% and 23% of children in child protection cases are unrepresented throughout the entirety of their case by either a guardian ad litem or a public defender.[1] While we have state mandates requiring representation, there remains an identifiable gap. Child representation is not only inconsistent but, arguably, insufficient due to lack of training and practice standards. Recent studies suggest that children desire and deserve a voice in all proceedings, but especially those that affect them.[2] Therefore, all children should have the right to effective, competent, and compassionate representation at all stages of a child protection case. It is not only important to the child, but also important to ensure fair process at every level and to keep families together.

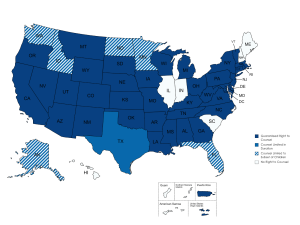

Idaho is one of only thirteen states that does not guarantee the right to counsel for children in child protection cases.[3] While there is no federal right to counsel for children during the pendency of child protection cases, most states have recognized the importance of counsel for children and have enacted state statutes. Though these statutes do not all look the same, they do encompass various models of representation guaranteeing children have a legal representative with rights and duties owed to them as the client.

In Idaho, any child who is at issue in a child protection case and under the age of 12 receives a Guardian ad Litem (“GAL”).[4] GALs are generally volunteers, often through the Court Appointed Special Advocate (“CASA”) offices which are in all seven judicial districts in Idaho. Under state statute, GALs shall be appointed counsel to represent them.[5] The GAL/CASA is a party to the case, receiving notice, the opportunity to be heard, and guaranteed representation.

If there is no GAL/CASA volunteer or program available, the court shall appoint an attorney to represent the child.[6] If the child is under 12 and has a GAL there is discretion for the court to appoint counsel for the child in “appropriate cases.”[7] The court may consider “the nature of the case, the child’s age, maturity, intellectual ability, ability to direct the activities of counsel and other factors…”[8]

Currently, there is no statewide judicial procedure for discretionary appointments; individual judges determine if children under 12 should be represented by counsel. The GAL is generally expected to convey the wishes of the child to the Court; however, there is no expectation nor obligation to request counsel for the child and/or comment on the factors the court considers for appointment. Thus, most children under the age of 12 are unrepresented by counsel and are not a party to their own case. A ten-year-old child could express disagreement with the GAL’s recommendations and have no means of presenting evidence to support his or her position. In addition, the child would be the only person in court expected to personally convey their thoughts, feelings, and preferences without an attorney standing beside them to aid and support.

Children 12 and older are appointed client-directed counsel to represent them.[9] This means that the child is the client, and the attorney owes the child the same duties as an adult client. For example, the attorney must work with the child to identify his/her legal objectives and abide by the child’s decisions concerning those objectives.[10] One of the most important aspects of child representation is counseling the child. Children may have diminished capacity, either because of their minority or trauma, and the attorney must engage in active, age-appropriate counseling to ensure a child can make informed decisions.[11]

Also, of paramount importance, counsel for the child owes a duty of confidentiality. In a child protection case, counsel is the only person with whom the child has protected confidential communications. Idaho Department of Health and Welfare caseworkers as well as GALs do not owe any fiduciary duties to the child; for example, conversations between the caseworker or GAL and child(ren) are not confidential and may very well end up in a report to the court and parties.

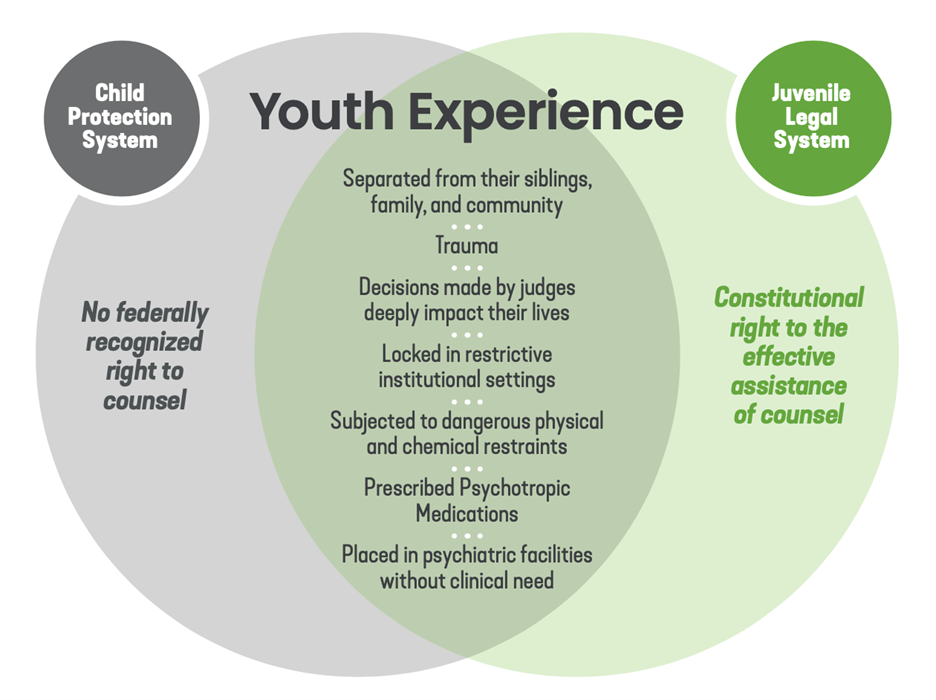

In contrast, children involved with the juvenile justice system, must be appointed an attorney if they are under 14 years of age.[12] Once the child reaches the age of 14, they can waive their right to an attorney.[13] Unlike children in child protection act cases, if someone under the age of 18 is charged with what would be a crime, an attorney is appointed to directly represent that youth. Due to Idaho also having no minimum age of criminal responsibility, some children as young as 7 are being charged with juvenile offenses and therefore represented by counsel.[14]

Children in juvenile justice and child protection cases experience similar losses and restrictions. They can each be removed from their families and communities and locked in facilities. In fact, it is not uncommon for two children to sit next to one another in a facility; one, who was placed there by way of the juvenile justice system, having been represented by counsel and being provided full due process with the other, a child removed from his home with custody vested in the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare, unrepresented, and placed in the facility by his caseworker without knowledge of the court.

Nationally, there is a shift towards guaranteeing representation of all youth and children in child protection cases by competent and well-trained attorneys. Separating children from their family and placing them in foster care is traumatic, life-altering, and potentially unsafe.[15] Foster care does not guarantee child safety and well-being. “In fact, […] the weight of social and scientific evidence suggests that children who are removed from their homes based on allegations of abuse and neglect often face more abuse and neglect in foster care. This is anathema to a system whose stated goal is child safety.”[16]

While children have the right to be placed in the “least restrictive, most family-like setting,” they are regularly placed in drastic alternatives like emergency shelters, hotels, institutions, and even the offices of the Idaho Department Health and Welfare.[17] In Idaho, children are also placed in homes rented and staffed by the Department, often in cities removed from their home communities and their families. Older children and those with disabilities face the most frequent overuse of institutional settings.[18]

A 2008 study by the Chapin Hall Center for Children at the University of Chicago found that children represented by attorneys in Palm Beach County had “significantly higher rates of exit to permanency” than children without access to legal counsel, while not decreasing rates of reunification.[19] Attorneys representing children can assist in moving the case toward permanency by independently investigating permanency options and advocating for the return of the child to parents when it is safe and appropriate to do so. Attorneys hold the Department of Health and Welfare responsible for its duty to care for children and provide reasonably necessary services and supports, as indicated in the court ordered treatment plan, to a family to facilitate the child’s exit from the foster care system and transition to a safe home. In this way, counsel for children provides a cost savings benefit to taxpayers by expediting the process to return home safely.

The child’s attorney focuses on the child’s number one legal problem – being in the custody of the state instead of a family. “Children have fundamental liberty interests at stake…” including the interest “in maintaining the integrity of the family relationships, including the child’s parents, siblings, and other familial relationships.”[20] While constitutional law is not often associated with child protection, the right to family integrity has long been recognized by the United States Supreme Court,[21] along with a recognition that “[n]either the 14th Amendment nor the Bill of Rights is for adults alone.”[22] Children’s representation should be important to all attorneys, as the child protection system and its outcomes (both positive and negative) impact nearly every other area of law and our communities. Children and youth deserve to be seen, heard, and well-represented. Their future, and ours, depend on it.

Jessalyn R. Hopkin

Jessalyn R. Hopkin is a Sr. Deputy Public Defender in Bannock County. She has spent the last four years specializing in juvenile and child protection cases. She is the Idaho State Coordinator for the National Association of Counsel for Children and is an at-large member of the Child Protection Section of the Idaho State Bar. The views expressed in this article do not reflect those of Bannock County offices.

Stacy L. Pittman

Stacy L. Pittman is a solo practitioner in North Idaho who practices across the state. She exclusively handles child protection cases, representing either the child(ren) or the guardian ad litem. Her previous experience includes working as a prosecutor, defense attorney, civil litigator, as a marketing and communications director in the health care field and working undercover for the police department in stings as a minor attempting to buy alcohol. She is a wife and mother who enjoys cooking, volunteering, and quoting Seinfeld.

[1] OFFICE OF PERFORMANCE EVALUATIONS, IDAHO LEGISLATURE, REPRESENTATION FOR CHILDREN AND YOUTH IN CHILD PROTECTION CASES, 2018, https://legislature.idaho.gov/wp-content/uploads/OPE/Reports/r1802.pdf. Children who come into foster care are often appointed a public defender or conflict public defender to represent them in a child protection case.

[2] Victoria Weisz, Twila Wingrove & April Faith-Slaker, Children and Procedural Justice, 44 Court Review 36.

[3] Right to Counsel Map, COUNSEL FOR KIDS, https://counselforkids.org/right-to-counsel-map/ (last visited September 4, 2023).

[4] Idaho Code §16-1614(1), Idaho Juvenile Rule 37(a).

[5] Id.

[6] Idaho Code §16-1614(1), Idaho Juvenile Rule 37(b).

[7] Idaho Juvenile Rule 37(a).

[8] Id.

[9] Idaho Code §16-1614(2), Idaho Juvenile Rule 37(a).

[10] Idaho Rules of Professional Conduct, Rule 1.2.

[11] Idaho Rules of Professional Conduct, Rule 1.14; see also American Bar Association Model Act Governing the Representation of Children in Abuse, Neglect and Dependency Proceedings, Section 7(c).

[12] I.C. 20-514(6); In re Gault, 387 U.S. 1 (1967).

[13] I.C. 20-514(5).

[14] As a juvenile attorney in Pocatello, Jessalyn and other attorneys in her office have been appointed to represent children as young as 7 in juvenile proceedings. Due to the confidentiality of the proceedings, some of which are still in process, specific names and cases cannot be discussed.

[15] Shanta Triveldi, The Harm of Child Removal, 43 NYU REV. L &SOC CHANGE 523, 524 (2019), https://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2087&context=all_fac.

[16] Id.

[17] https://idahonews.com/news/local/150-idaho-foster-children-spent-at-least-one-night-in-an-airbnb-in-2022.

[18] SARAH FATHALLAH, & SARAH SULLIVAN, AWAY FROM HOME: YOUTH EXPERIENCES OF INSTITUTIONAL PLACEMENTS IN FOSTER CARE, THINK OF US (2021), https://assets.website-files.com/60a6942819ce8053cefd0947/60f6b1eba474362514093f96_Away%20From%20Home%20-%20Report.pdf.

[19] ANDREW E. ZINN & JACK SLOWRIVER, CHAPIN HALL AT UNIV. OF CHICAGO, EXPEDITING PERMANENCY: LEGAL REPRESENTATION FOR FOSTER CHILDREN IN PALM BEACH COUNTY (2008), https://www.issuelab.org/resources/1070/1070.pdf.

[20] In re Dependency of M.S.R., 271 P.3d 234, 244, Wash. 2012.

[21] See Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U.S. 390 (1923), Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U.S.510 (1925), Troxel v. Granville, 530 U.S. 57 (2000).

[22] In re: Gault, 387 U.S. 1 (1967).

When Custody Mediation Orders Cause More Problems Than They Solve

by Tyrie J. Strong

Mediation is a useful and increasingly popular tool that, when used properly, helps resolve cases and reduce docket congestion. In family law matters, custody decisions reached through mediation tend to be more acceptable to the parties, thus minimizing conflict, as well as avoiding the ugliness of airing “dirty laundry” in trial.

However, a growing number of judges are indiscriminately issuing mediation orders in all family law cases without regard to the cost or appropriateness to a specific situation. These automatic orders sometimes require extensive mediation before the parties may even seek a temporary order pursuant to Idaho Rules of Family Law Procedure (“IRFLP”) Rule 504. When abuse is present, a court order that requires mediation prior to a hearing on a temporary order can lead to additional abuse.

Court orders requiring mediation, whether to impasse or for a minimum of three sessions, can undermine access to justice for low-income or pro se parties. Mediation is popular and mediators are busy. In my experience, mediators typically have full schedules one to three months out. This means that merely requiring even a single mediation session before hearing a motion for temporary custody, support, or other matters, may add months of delay.

When mediation is required before a motion for temporary order can be heard, it may: (1) ignore safety concerns such as domestic violence, or financial concerns such as a pressing need for child support; (2) add to docket congestion by increasing the number of civil protection orders filed in an attempt to address custody issues; or (3) result in more failed mediation efforts and thus more cases going to trial due to rushing to mediation prematurely, perhaps even before discovery is completed.

Mandatory Mediation May Harm Low-Income Persons

A mediation order that requires mediation for a certain amount of time, such as “to impasse” or for “three sessions” denies moderate- to low-income parties’ access to justice by ignoring the party’s financial resources. Moreover, requiring a certain number of mediation sessions may waste parties’ time and money if impasse is achieved sooner – while specifying “to impasse” has the potential of requiring an unlimited number of mediation sessions.

Family Court Services funding is only available for up to six hours of mediation, and exclusively for custody and visitation issues. Mediators in District 1 reserve time in three- or four-hour blocks that cost an average of $1000.[i] I surveyed attorneys in most judicial districts and found their costs to be in the same range. These costs are typically equally split between the parties, although the IRFLP state that the default is for them to be apportioned pro-rata based on the parties’ income.[ii]

Mediation for three sessions is approximately $1500 each, to which 43% of Americans do not have ready access.[iii] Since Idaho’s median household income ranks 32nd among states – in 2021, approximately $6,000 less than the national average[iv] – it is reasonable to infer that a significant percentage of Idahoans would not readily have access to the funds for such mandatory mediation. For survivors of domestic violence, the situation is worse: a recent study shows they have access to an average of a mere $288.90; that is not savings, but what they have access to in totality.[v]

Six hours of mediation is not always sufficient to reach impasse,[vi] leaving lower-income parties who qualify for Family Court Services funding unable to pay for additional hours of mediation to achieve resolution or impasse. Therefore, in many cases parties only have four hours before running out of Family Court Services’ funds, since the remaining funds will not cover a second four-hour mediation session.

An order that requires mediation before a temporary order hearing may be scheduled also significantly delays the parties’ access to relief through the court system and creates pressure to accept any custody agreement for those who cannot afford the court’s requirements.[vii] For example, when a party desperately needs child support, the parties’ children may not be financially provided for during the delay caused by such orders and this may lead to housing or food insecurity. Additionally, in cases where financial abuse is present (i.e., no access to marital resources; not paying rent; destroying the partner’s credit; etc.) or there is a single wage earner, these financial issues may be exacerbated and lead to further pressure to mediate an unfair agreement to obtain some financial relief.

The Idaho Constitution admonishes the courts to dispense justice in Article 1, § 18: “Courts of justice shall be open to every person …” Thus, Idaho waives court filing fees for those who cannot afford it so their access to justice is maintained. These fees are all $250 or less.

However, such mandatory mediation orders threaten a low-income party, particularly one that is pro se, so that the judge refuses them a hearing on a motion for a temporary order or a trial in their case because they cannot afford mediation costs and then cannot comply with an order mandating mediation.[viii] This denies those without resources access to justice. Moreover, this denial of access to justice to indigent litigants may constitute a violation of the Idaho Constitution as well as the Equal Protection Clause of the United States Constitution.[ix]

Delaying Temporary Orders Ignores Safety Issues

A temporary order is often sought for safety reasons, but those safety reasons may not immediately meet the threshold of an “emergency” to bypass an order for the parties to attend mediation prior to scheduling a hearing on a motion for a temporary order.[x] When safety issues exist, a temporary order is needed quickly. Based on my experience, I have created a partial list of a few situations that underscore a party’s need for a temporary order quickly in the box on this page. This list shows how a court order requiring mediation before a temporary order hearing, and especially without considering the presence of domestic violence, denies parties relief, endangers children, and may create more problems than it solves.

Non-Emergency Situations That Require Prompt Temporary Orders

- Emotional abuse inflicted on the parties’ child(ren) which can lead to severe mental distress, resulting in a child self-harming or experiencing suicidal ideation, including:

- putting down the child;

- exposing the child to age-inappropriate situations or material, such as pornographic films;

- emotionally blackmailing the child(ren), such as threatening to put them in foster care; and

- physical abuse of the other parent in front of the parties’ child(ren);

- Emotional abuse of the other parent (experiencing a child being blackmailed; following them around while both provoking them and recording their reactions; angry outbursts and acts of violence such as throwing objects or punching walls, etc.);

- Financial abuse (no access to marital resources; not paying rent; destroying the partner’s credit);

- A desperate need for child support, such as when only one parent works, leading to housing and food insecurity;

- Inadequate supervision of the child by one party, leading to safety concerns and injuries, such as:

- falling in unsafe environments;

- access to sharp or other age-inappropriate dangerous objects;

- wandering off and being hurt; or

- fights with or being bullied by neighborhood children;

- The custodial parent withholding the child(ren) from the other party.

Mediating Under Pressure Leads to Bad Agreements

The purpose of mediation is to reach resolutions that work better for and are more acceptable to the parties than a judicially imposed decree, as well as to achieve them more quickly than a full trial would allow, thus reducing court congestion. However, mediation conducted under unrealistic time pressures or extreme emotional stress can work against these benefits.

Pressure to resolve the issue in mediation can come from many sources. One is when judges require mediation before a desperately needed temporary order can be sought. Another is when the mediation order contains a challenging time deadline, such as achieving one, or even multiple, mediation sessions within 42-45 days when, often, the mediators’ schedules cannot accommodate that. This most impacts those who are pro se and may not know that a judge will often not find contempt when a party is making their best efforts to comply with the court order. A third is when there is an order to mediate for more sessions than Family Court Services can fund when a party cannot pay for it, exacerbated by replacing the pro-rata funding specified in IRFLP 603(h) with a 50-50 cost-sharing order. And lastly, when one party is a bully or abuser who misuses the situation to force his or her will on the other, mediation is not appropriate, as recognized by IRFLP 601 (c)(2)(B) and the American Bar Association,[xi] discussed below.

In each of these situations, instead of mediation leading to a good arrangement, a disadvantaged party is pressured to accept an agreement that will likely need to be modified in the future because the disadvantaged party believes that accepting any agreement is better than no agreement. For example, a terrible custody arrangement is better than continuing to live under abuse, and agreeing to inadequate child support today is better than continuing without any child support and losing your home. Any property/debt agreement is better than risking a fine or jail time for noncompliance with an order because you could not pay for the number of mediation sessions ordered. All these concerns result in a denial of justice to pro se or low-income people contrary to the Idaho Constitution.[xii]

Inappropriate Mediation Orders Increase Docket Congestion

Custody Issues are Pushed into CPOs

In my experience, most judges will agree that civil protection orders (“CPOs”) are for emergency safety issues, and not for resolving custody disputes. The idea is to bring these issues to the judge who will be working extensively with a family in a divorce or custody case. To this end, CPOs are sometimes only granted for long enough to enable a party to seek a temporary custody order.

An order to mediate (especially to impasse or three times) before a temporary custody motion will be heard can result in another motion filing and hearing to extend a CPO protecting the parties’ minor child(ren). This wastes court time and resources and does not promote judicial efficiency. Further, the judge hearing the CPO extension is not able to issue a detailed temporary custody order covering the family’s needs until the trial, so a temporary order is still needed.

Mediating early and fast leads to more trials

In cases involving domestic violence, if a temporary order cannot be sought until after mediation, the presence of safety issues creates an unreasonable pressure to mediate early and quickly. Parties then see mediation as a hurdle to cross rather than a process to fully engage in. There is pressure to take the first mediator available, regardless of personal preference or relevant qualifications to a case, and to reach impasse in one session if impasse is required by a court order, so that a party’s Motion for Temporary Order can be heard.

In my experience, early mediation is more likely to fail than mediation engaged in closer to trial for several reasons. Mandatory disclosures and discovery take time to complete, and engaging in mediation while lacking necessary information to make informed choices increases the likelihood of fruitless mediation. Once Family Court Services funding is used up, even after “wasting” it on mandatory additional mediation, it is gone, and lower-income parties would not be able to mediate again later.

Another reason is that time helps parties be open to more solutions. At the beginning of the court process, the parties may be at their most rigid regarding their desired goals. Parties gain flexibility as they work through issues, information comes to light through discovery, and they live with a custody arrangement on a temporary basis. Later, with a temporary order in place and mandatory disclosures provided, mediation may be more likely to succeed.

Next, in cases involving physical or sexual domestic violence, the results of any pending criminal cases may be necessary to successfully mediate a case. Criminal cases are often concluded before a civil case reaches trial, and they can help provide direction related to a party’s custody concerns. Even if the criminal matter has not been resolved, the parties gain an increasing understanding of likely outcomes as the criminal case progresses, which facilitates a mediated resolution as they learn the strength of their position.

And finally, as trial approaches, parties tend to better appreciate the emotional and financial costs of trial, and this may increase their flexibility when mediating.

Thus, although early mediation may appear to be a way to reduce docket congestion by rapidly resolving cases, I believe the opposite to be true: it is more likely to fail through either non-agreement requiring trial now, or a pressured unworkable agreement requiring another lawsuit to modify the agreement. This, I argue, consumes more of the court’s time than simply hearing a Motion for Temporary Order.

Additionally, pushing custody issues into CPOs also clogs court dockets and involves more judges in a case.

Procedural Issues

IRFLP and Domestic Violence

The IRFLP address mediation, echoing and replacing Idaho R. Civ. Proc. 37.1. If a child is involved, IRFLP rules 601 and 602 apply.

IRFLP 601 authorizes screening on a case-by-case basis as to whether mediation is appropriate. Consequently, the rules acknowledge that mediation is neither automatic nor appropriate for all family law cases. Screening involves several factors, enumerated in IRFLP 601(c)(2), which include the presence of domestic violence.

When domestic violence or other specified issues are present, mediation may not be appropriate. Indeed, the American Bar Association recommends an opt-out provision when domestic violence is present,[xiii] and the consensus in academic literature is that caution is needed with mediation when there is domestic violence, as it is not always safe or appropriate,[xiv] due to the power imbalance between the parties.

IRFLP 602(b) provides for mediation only when custody of a minor child is at issue (which is when Family Court Services funding is available). IRFLP 603 applies to issues other than custody and visitation. IRFLP 603(d) grants a court discretion to order mediation in these cases if all parties agree that mediation would be beneficial.

Impossible Deadlines

In my experience in Idaho’s Judicial District 1, mediation is used extensively. Most judges in District 1 order mediation for every family law case, which results in full calendars for mediators and scheduling delays for parties.[xv] Thus, automatic mediation orders for all cases ignores the need to assess the appropriateness and timing of mediation for each case and can also result in impossible deadlines because they do not consider mediators’ availability.

Recommendations

In order to avoid these problems and make mediation more effective, I propose (1) a status conference based upon parties’ affidavits be held before mediation orders are issued, and (2) a removal of mandatory mediation between the parties as a pre-requisite for a party being able to file a motion for a temporary order.

At this proposed status conference, courts would ideally:

Mediation orders are generally not appealable and an interlocutory appeal is nearly impossible which leads to additional concerns related to a low-income or pro se party’s access to justice in their family law case.[xvi] When a pro se or low-income party agrees to a decree out of financial desperation or to comply with a court order and that is not in the best interest of the child(ren) or is unsafe or unfair to that party, equal access to justice within the court system is unavailable. Similarly, when an abused party feels pressured to agree to anything, even an agreement that is bad for that party or the minor child(ren), rather than have no agreement because they cannot obtain a temporary order for relief, the justice system has failed that party.

Tyrie J. Strong

Tyrie J. Strong worked at Intel as a Software Engineer before attending Gonzaga University School of Law. She graduated magna cum laude with her J.D. in 2021. She now helps survivors of domestic violence through her work at Idaho Legal Aid Services, Inc. in Coeur d’Alene. She is also on the Board of Directors for Safe Passage, a domestic violence agency in Coeur d’Alene.

[i] Of the 14 mediators listed for Kootenai county and 9 mediators in Bonner County, I have previously spoken with and had the pricing for 5 of them, 3 of which were available in both counties. (There is no list of mediators in Benewah, Shoshone, or Boundary counties.) Prices ranged from $200 to $300 per hour, with an average of approximately $250/hour. Two scheduled sessions in 3-hour blocks, two scheduled sessions in four-hour blocks, and one did not specify.

[ii] IRFLP 603(h), discussing mediation of all family-law matters other than custody, which is covered by IRFLP 602 and does not discuss compensation of the mediator, presumably because Family Court Services funding is available. However, a recent proposed rule change would divide costs equally under IRFLP 602 for custody and visitation matters, which could further the power imbalance when there is financial abuse occurring after Family Court Services funding is exhausted.

[iii] Annie Nova, Just 43% of Americans say they could come up with $2,000 for an emergency, CNBC (June 26, 2019), https://www.cnbc.com/2019/06/26/less-than-half-of-americans-have-2000-in-emergency-savings.html.

[iv] https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/ID,US/HSG860221.

[v] FreeFrom, Support Every Survivor: How Race, Ethnicity, Gender, Sexuality, and Disability Shape Survivors’ Experiences and Needs 50, Available at: https://www.freefrom.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Support-Every-Survivor-PDF.pdf.

[vi] I have mediated a case for 12 hours – double the amount of family court services funding available. I can conceive of more complicated cases that may mediate even longer before impasse or resolution.

[vii] These lower-income people are often pro se, and generally do not know that they could file a motion requesting relief from the judge’s order, nor how to file such a motion even if they knew it was possible. I have not seen an order allowing for financial relief or instructing parties how to pursue it if needed. A recent order given to a lower-income pro se party made no such allowance beyond the 6 hours of funding from Family Court Services available.

[viii] Id.

[ix] Idaho Constitution, Article I, Section 18; U.S. Constitution, 14th Amendment (“No state shall … deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”).

[x] A temporary order may be sought under IRFLP 504. IRFLP 505, Temporary Order Issued Without Notice, provides for an expedited temporary order when there is an immediate and irreparable risk of harm.

[xi] American Bar Association, Mediation and Domestic Violence Policy (July 2000). (“That the American Bar Association recommends that court-mandated mediation include an opt-out prerogative in any action in which one party has perpetrated domestic violence upon the other party.)”

[xii] Idaho Constitution, Article 1, Section 18.

[xiii] U.S. Constitution, 14th Amendment.

[xiv] See, e.g., Gabrielle Davis, Loretta Frederick, and Nancy Ver Steegh, Intimate Partner Violence and Mediation: A framework for when and how mediation should be used, Dispute Resolution Magazine (Apr 1,2019). https://www.americanbar.org/groups/dispute_resolution/publications/dispute_resolution_magazine/2019/spring-2019-family-matters/11-davis-et-al-safer/; Jan Jeske, Custody Mediation within the Context of Domestic Violence, 31 Hamline J. Pub. L. & Pol’y 657, 661 (2010) (power and control dynamics leave victims little bargaining power with their abuser, leaving “victims of domestic violence in danger of ‘forced’ mediated custody agreements that do not serve their or their children’s best interests.”); Sarah Krieger, The Dangers of Mediation in Domestic Violence Cases, 8 Cardozo Women’s L.J. 235, 245 (2002) (Arguing against mediation where domestic violence is present, because the power and control dynamics between the couple make it difficult or impossible for the victim/survivor to adequately negotiate a fair agreement); Emma Katz, Domestically Violent Men Describe the Benefits of Abusing Women and Children, Dr. Emma Katz Substack ( July 11, 2023), available at: https://dremmakatz.substack.com/p/domestically-violent-men-describe.

[xv] A recent proposed rule change to the IRFLP suggested mandating that the first mediation session occur within 42 days of the order to mediate. When mediation is ordered indiscriminately at the start of the case, this may be impossible time-wise or restrict parties to an available mediator. Additionally, it introduces all the issues of mediating too soon, prior to discovery, prior to parties understanding the case well enough to be successful.

[xvi] See Stephen Adams and Christopher Pooser, Interlocutory Appeals in Idaho, Idaho State Bar (Feb. 1, 2023), available at: https://isb.idaho.gov/blog/interoluctory-appeals-in-daho-is-there-a-better-process/.

QDROS: Because Divorces Aren’t Complicated Enough Already

by Natalie Greaves

It is sometimes said that family law attorneys have the best stories, and that might be true. What other attorneys can share stories of litigants gluing drawers together prior to transferring property, arguing over dishes and collectible dolls, and having trial testimony about dead turtles?[i] The stories range from the ridiculous to the heartbreaking. It is also true that family law attorneys also often deal with an extremely high case load, multiple required filings, and court appearances in every case, and emotionally charged litigants who are trusting their attorneys to help in the most difficult time in their lives. Attorneys who do not practice family law might also be surprised by the highly varied, complex, and high dollar assets and issues that come across a family law attorney’s desk all day long every day. One of those issues involves dividing retirement assets in a divorce.

The Basics

A Qualified Domestic Relations Order, or QDRO (pronounced “kwä-drō”), is a court order for division of certain retirement assets in divorce. It is the only allowable method of assigning applicable retirement assets to a person that is not the participant in the account, and if done correctly, is an exception to the rule that removing retirement assets will create a penalty and taxable income.[ii] It has two primary functions: 1) it tells a retirement plan administrator how to divide the asset; and 2) it provides basic identifying information about the plan and the parties.

For many individuals, retirement benefits may meet or even exceed the net equity value of the community home as the largest single asset to be divided in divorce. This is particularly true with the changing demographic of divorce litigants. According to data from the U.S. Census Bureau in a report issued in 2021,[iii] divorce rates for people over 50 have doubled since 1990 and tripled for those over 65. In 2021, 34.9% of all Americans who got divorced in the previous calendar year were aged 55 or older-twice the rate of any other age group. These individuals have had many more years to accumulate retirement assets that must be divided in an equitable manner.

There are many kinds of retirement assets. A defined contribution plan is a 401(k), 403(b), or similar plan. These plans have a particular dollar value and a QDRO for this kind of account results in a one-time event that segregates the account into two. A defined benefit plan, also known as a pension plan, results in monthly benefits calculated by actuaries based upon a person’s life expectancy paid out as annuities.

Typically, other retirement assets such as Individual Retirement Accounts do not require QDROs, as the plan participant should be able to simply initiate a request called a “transfer incident to divorce” that sends the correct portion to the former spouse’s new or existing IRA. However, plan administrators sometimes still request division orders for these accounts for their record-keeping. Other assets subject to division such as military retirement, Thrift Savings Plan accounts, and Federal Employees Retirement System accounts utilize different terminology for the caption of the division order, the naming of the parties, and substantive requirements for the orders which are beyond the scope of this article.

To be a valid QDRO, the order must meet specific criteria. The person named on the account is called the “participant.” The former spouse that receives a portion of the participant’s account is typically called an “alternate payee.” A QDRO directs the plan administrator of the account to pay a certain amount or percentage of the account directly to the alternate payee by segregating his or her portion into a separate account from the participant’s funds.[iv] The alternate payee can choose to keep the account with the same plan administrator, or they can roll it over to a preexisting account or a new account. This allows the alternate payee to adopt his or her own investment strategy and avoid continued direct involvement with the participant about the asset.

Dividing a retirement asset is not the only use for a QDRO. Though certainly more rare, other acceptable uses include pre-divorce judgments for support and attorneys’ fees, post-divorce spousal maintenance (including separate contracts for maintenance not included in a Decree),[v] related attorneys’ fees,[vi] child support orders not merged into a final divorce decree, or child support arrearages.[vii]

There are some inherent limitations in QDROs as well. A QDRO cannot determine how federal taxes are to be paid, meaning that even if a QDRO were to state that the participant was to keep the federal tax liability for amounts assigned to the alternate payee, doing so would be invalid under section 402 of the IRS code.[viii] A workaround for this issue would be to instead require reimbursement of any taxes paid in the divorce decree as a way to limit the tax impact on the alternate payee.

Another limitation of a QDRO is procrastination often creates further litigation. Consider the following examples. First, the United States Supreme Court ruled in Boggs v. Boggs that ERISA preempted state law to protect an alternate payee’s interest from a deceased participant’s testamentary heirs, even though a QDRO had not yet been entered.[ix] The Court found that QDRO rules in this case meant that a testamentary transfer would be an ERISA-prohibited alienation. Next, a Ninth Circuit case, Ablamis v. Roper,[x] dealt with the death of the alternative payee and held that the nonemployee spouse could not validly bequeath her portion of the surviving employee’s pension benefits to a third party under California’s community property law.

Though there are only a handful of reported Idaho cases regarding QDROs, one case involved a Decree that awarded one half of a 401(k) account to an alternate payee.[xi] Between the date of divorce and the date that the QDRO was entered, the value as found at the time of divorce had dropped precipitously. The Decree stated that the alternate payee was assigned 50% of the 401(k) value “as of the date of divorce.”[xii] The drafted QDRO had similar language, but also had a separate provision in the QDRO that stated that if the “aggregate amount of benefits . . . is reduced, any such reduction shall be shared by the parties on a pro rata basis.”[xiii] The Court affirmed both the Magistrate and District Courts, finding that the reduction paragraph did not specifically refer to gains and losses based on market fluctuations, and also finding that the Decree was clear as to the date of valuation.[xiv] The Court did agree with the District Court’s ruling that the Magistrate Court could not require the participant to pay the difference from other funds, but only through the further division of the 401(k), even though it resulted in him receiving less than half of the actual account value at the time of the division.[xv] The Court specifically rejected the argument from the participant that doing so would be considered an unequal division.

The Process

After the entry of the Decree, a draft QDRO should be completed. To do so, a signed release of information form will likely need to be obtained from the participant to receive necessary specifics from the plan administrator. If the practitioner is not familiar with the plan or plan administrator, it is often advisable to request preapproval, although some plan administrators will refuse. If preapproval review is available as an option, this should be done prior to having the Court sign the QDRO to avoid having the Court need to sign multiple QDROs if there are corrections to be made which can be frustrating and time-consuming for all involved. The plan administrator may require changes to be made which must be reviewed carefully to ensure that the QDRO is not being interpreted incorrectly, especially for mixed separate and community assets as occurs when some of the account was earned prior to marriage. Most judges will require a signed stipulation when submitting the QDRO, even if the Decree states the division and the Decree was entered by stipulation. his is with good reason, as a drafted QDRO can sometimes not match the intention of the parties if it is not properly reviewed. Once the Court signs the QDRO, a copy along with a certified copy of the Decree should be sent to the plan administrator to effectuate the division.

Best Practices for QDRO Language in a Decree

Whether a family law practitioner intends to draft the QDRO herself, or seek outside counsel to handle the drafting, certain language should be present in the Decree to avoid confusion and unintended consequences.[xvi] First, the Decree should state who is drafting the QDRO, either by naming one of the litigant’s divorce counsel, or by designating a neutral outside counsel to effectuate the intentions of the Decree. Neutral counsel can be helpful when distrust is high between litigants or simply when practitioners are busy with other deadlines and cases. The Decree should also state that the Court will reserve jurisdiction until the division is complete.

Second, the Decree should be specific in naming which accounts are to be divided. If there are premarital retirement accounts or accounts that are simply not going to be divided even if they are community, it is still important to name each of these in the Decree. The naming of the accounts in the Decree should be specific enough that a person not involved in the case can identify them.[xvii] At a minimum, the plan administrator will review the Decree and compare it to the QDRO and there should be enough specificity to avoid confusion. Particularly if there are multiple accounts with the same plan administrator, this may create an avoidable issue. Avoid simply referring to a property and debt schedule and instead list these accounts directly in the Decree, even if they are also listed in the schedule.

Specificity is also required in designating what portion of the account is assigned to each party. This can typically be either a dollar figure or a percentage. A mixture of the two could potentially be possible if written correctly, but this is more rare and more difficult to determine the order of operations and designations, which can result in rejection by the plan administrator and likely create an unnecessary headache when there would be a better way to word a QDRO or do the division.

The Decree should also state who is paying for the QDRO division costs and include a deadline for payment upon request and for requested signatures. This should not state when the QDRO will be completed, as the plan administrators vary greatly in how long they take to process a QDRO but should instead only have dates that are within the control of the parties. Regarding cost, some plans are now passing on division costs to participants and alternate payees. This amount can vary and is deducted from the amount awarded to each party absent some other designation in the Decree. It is rare to know this until after the Decree is already entered, but preemptive language could be added if one party is going to be assigned this cost if it occurs.

Additionally, the Decree should state how gains and losses subsequent to the Decree are to be handled and whether only one party will be bearing this risk or whether the parties are subject to these in pro rata or in some other manner.

Finally, depending on the type of retirement asset, survivor benefits may be available to a former spouse. Sometimes these have a cost that lowers the amount that both parties will receive and sometimes there is no cost.[xviii] This is only an issue for pension accounts and defined benefit plans, rather than defined contribution plans, but should still be considered in Decree drafting. For defined contribution plans, language should be included as to what will happen if either party passes away prior to the division being final. For example, consider a case where an alternate payee dies post-divorce but prior to division. The issue might become whether her heirs are entitled to receive her portion of the former spouse’s 401(k) awarded to her in the divorce or whether her portion reverts to the former spouse since the division had not occurred. Having specific language that had been stipulated to by the parties prior to the divorce might help avoid this even being an issue that would need to be decided.

Conclusion

Though I do many referral cases with one or two divorce counsels of record who want to have a neutral attorney handle the QDRO based on complexity or convenience, many of my QDRO cases are to fix issues that have already occurred, or QDROs that simply have never been completed, including one current case with a Decree from 2003. There is good reason for this, as both the attorneys and litigants often feel that the case is over and tying up the loose ends of completing the QDRO is low on the list of priorities. At other times, the Decree is not stale, but either lacks the necessary language, or the intention of the parties is not something that can be accomplished by the plan administrator. Sometimes a drafted and entered QDRO is just simply incorrect, which the parties do not realize until after the division occurs. Though QDROs are likely not as exciting as other aspects of family law, they are incredibly important to complete correctly and in a timely manner to help preserve and protect client rights. As a practitioner, having a QDRO become an exciting part of the litigation is probably something that is best avoided by establishing a system of best practices for dividing these assets.

Natalie Greaves

Natalie Greaves is the managing attorney at Boise Law Group, PLLC, and is licensed in Idaho and Arizona. Natalie provides QDRO services directly to clients as well working as a neutral QDRO attorney for other litigators who wish to outsource QDRO preparation. She also practices family law litigation and is a Supreme Court Certified Child Custody Mediator. For fun, she travels the world but especially prioritizes visiting any locations occupied by her family.

[i] Reading this footnote means that you want to know if these are true stories. Yes, unfortunately.

[ii] Qualified Domestic Relations Orders are anticipated by Section 206(d)(3) of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974, as amended (“ERISA”) and Section 414(p) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended.

[iii] Number, Timing, and Duration of Marriages and Divorces: 2016 Current Population Reports By Yerís Mayol-García, Benjamin Gurrentz, and Rose M. Kreider Issued April 2021 P70-167.

[iv] For pension accounts, it is a little more complicated and the accounts are not necessarily segregated based on factors such as whether the employee has begun receiving benefits or whether there is a prior spouse.

[v] Kesting v. Kesting, 160 Idaho 214, 370 P.3d 729, 733 (2016) (“We conclude that the provisions of Title 11 of the Idaho Code that provide for attachment of exempt property to enforce claims for support are part of Idaho’s domestic relations law.”)

[vi] Boggs v. Boggs, 520 U.S. 833, 841, 117 S.Ct. 1754, 138 L.Ed.2d 45 (1997).

[vii] 29 U.S.C. § 1056.

[viii] See e.g., Clawson v. Commissioner, T.C. Memo 1996-446 (1996).

[ix] Boggs, 520 U.S. at 841.

[x] Ablamis v. Roper, 937 F.2d 1450 (9th Cir. 1991).

[xi] Grecian v. Grecian, 140 Idaho 601, 603, 97 P.3d 468, 470 (Ct. App. 2004).

[xii] Id.

[xiii] Id. at 603-604, 97 P.3d at 470-471.

[xiv] Id. at 604, 97 P.3d at 471.

[xv] Id.

[xvi] A stand-alone document is not required to be a QDRO. Instead, it could be any judgment, decree, or order”, including a divorce decree. However, the plan administrator has wide leeway in determining whether a document meets their requirements, and it is likely much easier and more efficient to present the information in a way that they expect to receive it.

[xvii] For example, rather than including only the designation of “401(k) account” in the Decree, it is preferable to say, “Fidelity 401(k) account” or better yet, include a few of the final digits of the account number, such as “Fidelity 401(k) account ending in ***370”.

[xviii] For example, under a Federal Employees Retirement System division order, a survivor benefit permanently reduces the monthly benefit that would be received by both parties.

More than Just Paper: The Rising Popularity of Premarital Agreements

by Jorge E. Salazar

In popular culture, prenuptial agreements have received their fair share of criticism, and the legal community has likewise viewed these agreements with varying degrees of disfavor over time. Laypeople and legal professionals hold valid concerns that the types of agreements, whether called prenuptial agreements, premarital agreements, or prenups, will prove unenforceable. For instance, Idaho is among the states that will not enforce provisions of a prenup that would render a spouse eligible for public assistance.[i] Such policies may discourage individuals from even considering a premarital agreement, because they perpetuate the popular belief that prenups are “not worth the paper they’re written on.”

These views have some merit. Where the legitimacy of a prenup is at issue, courts must essentially engage in “double litigation” to first assess the validity of the premarital agreement, and if unenforceable, only then can the court commence with the process of property division and dissolution. Double litigation can lead spouses who find the outcome of their divorce did not align with their often long-held expectations to feel frustration and disappointment. It can also lead to increased legal expenses.

However, drafting an effective premarital agreement can greatly benefit marital partners and the legal system. An adequately prepared premarital agreement acts to conserve judicial resources by avoiding this “double litigation” issue, and it permits a couple to divorce and have their assets divided as they previously agreed. By resolving marital settlement issues such as property distribution in advance, effective prenups ensure that a divorce can be granted more expediently, thereby conserving the resources of both parties and the courts.

Furthermore, despite their reputation for creating problems between intended spouses, premarital agreements may help couples avoid the pitfalls that commonly lead to marital problems and divorce.[ii] Because a properly drafted and executed premarital agreement requires the partners to communicate about their finances before issues arise during their marriage, couples who prepare premarital agreements are often better equipped to handle the financial issues that inevitably occur during any marriage.[iii] Spouses can decide in advance how they will manage their earnings and the couple’s financial goals as they build their shared life.[iv] Rather than signaling the imminent end of a marriage, executing a prenup may help spouses remain together through the difficulties that inevitably arise during any marriage.

Premarital agreements can be a valuable tool in the arsenal of lawyers who practice family law, and they should not be disregarded because of problems that are easily avoided using careful and conscientious legal practices. This article will first discuss trends in marriage, then turn to the principles of how to properly produce and execute a premarital agreement that works to preserve a client’s resources and judicial economy, rather than creating new issues to litigate.

Trends in Marriage and Popularity of Premarital Agreements

The reality is that among the marrying-age population, divorce is much more foreseeable than it has been for previous generations.[v] It may surprise some that the highest divorce rate is among Baby Boomers, individuals born between 1946 and 1964.[vi] Although the national divorce rate has declined over the last two decades, for 55- to 64-year-olds, the divorce rate has doubled and tripled for the over-65 group.[vii] These divorces tend to occur after a couple’s children are grown, when spouses realize they no longer share the same interests and seek to end the marriage to pursue their wishes during retirement.[viii]

The children of Baby Boomers, who are primarily members of Gen X and Millennials, are responding accordingly to this increasing rate of divorce among their parents’ generation.[ix] While the divorce rate is lowest in Gen X, it seems that Millennials are responding to the heightened divorce rate in their parents’ generation by marrying less often and later in life.[x] Recent spikes in premarital agreements show this cautious attitude that Millennials display towards marriage and their realist views of the likelihood of a marriage ending in divorce.[xi]

Indeed, the current population that is of age of marriage is more interested in premarital agreements than previous generations. Nearly two-thirds of the divorce attorneys surveyed by the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers reported an increase in the total number of clients requesting prenuptial agreements in recent years, and over half of those attorneys indicated Millennial clients drove the increase.[xii]

Legal Principles

The distribution of assets in divorces without prenuptial agreements follows a specific legal framework. For example, Idaho is a community property state that operates under the principle that all property acquired after the marriage is jointly owned by both spouses, regardless of who earned or purchased it.[xiii] The term property includes rents, issues, and profits of all property. [xiv]

During divorce proceedings, the court’s primary goal is to divide community assets equally, aiming for a 50-50 split, with each spouse receiving an equal share of the community property.[xv] But, if compelling reasons exist to not divide property equally, the court may divide community property in another way while considering relevant factors.[xvi]

On the other hand, separate property is any property acquired before the marriage, through inheritance, or gifts.[xvii] Separate property may also be established by a written agreement (such as a prenuptial agreement) between the parties that declares that some community property item(s) will be considered separate property of one spouse.[xviii] Accordingly, separate property remains with the respective owner. But it’s crucial to establish and prove the separation of such assets during divorce proceedings. Therefore, without a premarital agreement, Idaho operates under the principle that both spouses jointly own property acquired during the marriage.

Additionally, it is important to understand that Idaho courts have applied contract law to premarital agreements.[xix] Contract principles that have been applied to premarital agreements include voluntary abandonment, which the conduct of the parties can infer.[xx] It may, therefore, be wise to instruct clients to consistently act in accordance with the premarital agreement, lest it be deemed abandoned or otherwise precluded from enforcement by other principles of contract law.

The Idaho Code also includes provisions that pertain to premarital agreements. But, they can be somewhat vague in that they reference requirements that are only articulated in other provisions of the code. For instance, Idaho Code § 32-922 requires certain formalities for the execution of premarital agreements, which are found by a review of Sections 32-917 through 32-919.[xxi] These are virtually identical to the formalities for writing and executing contracts for the conveyance of real estate, which again requires consultation of different statutes within Title 55.[xxii]

Idaho Code § 32-922 also requires that premarital agreements conform with the rules that are required for executing marital settlement agreements.[xxiii] Although derivative, this means that attorneys drafting premarital agreements can essentially approach the process as if drafting a settlement agreement for a divorce. This provision also has practical benefits: it reduces the resources that clients and courts must expend should the couple’s marriage ultimately end, as the settlement agreement was essentially drafted in advance.

Attorneys should also be aware that the Idaho Code expressly allows the enforcement of a premarital agreement where a marriage is found to be void, but only to the extent necessary to avoid an inequitable result.[xxiv] The Idaho Code also permits courts to order a party to pay spousal support notwithstanding the existence of a properly executed premarital agreement, where the agreement includes a provision that modifies or eliminates spousal support, and that provision causes one party to the agreement to be eligible for support under public assistance at the time of separation or marital dissolution.[xxv] As such, attorneys should take particular care in drafting and producing premarital agreements, where an intended spouse lacks separate property or has limited education or employment capabilities that may put them at risk of requiring public assistance in the absence of spousal support.

Safeguards for Enforceability