Month: September 2023

Redacted Idaho Supreme Court Order adopting the majority “entire file” rule

The Idaho Supreme Court has issued an Order regarding the scope of documents a lawyer is ethically required to surrender to a former client under Idaho Rule of Professional Conduct 1.16(d). Please click the link below to review a redacted copy of the Order.

Consistent with the Court’s Order, the Idaho State Bar Board of Commissioners is evaluating a proposed change to the Idaho Rules of Professional Conduct reflecting the Court’s adoption of the “entire file” rule and to address what file materials fall under the “narrow exceptions” category.

Comments Sought on Various Idaho Rules – Deadline 10/5

Comments Sought on Idaho Rules of Family Law Procedure

The Idaho Supreme Court’s Children and Families in the Courts Committee is seeking input on proposed revisions to the Idaho Rules of Family Law Procedure. A copy of the revisions can be found on the court’s website at https://isc.idaho.gov/main/rules-for-public-comment. Please send your comments to Deena Layne, dlayne@idcourts.net by Thursday, October 5, 2023. Thank you.

Comments Sought on the Idaho Juvenile Rules (C.P.A.)

The Idaho Supreme Court’s Child Protection Committee is seeking input on proposed revisions to the Idaho Juvenile Rules (C.P.A.). A copy of the revisions can be found on the Court’s website at https://isc.idaho.gov/main/rules-for-public-comment. Please send your comments to Deena Layne, dlayne@idcourts.net by Thursday, October 5, 2023. Thank you.

Comments Sought on the Idaho Appellate Rules and the Idaho Rules of Civil Procedure

The Idaho Supreme Court’s Child Protection Committee is seeking input on proposed revisions to the Idaho Appellate Rules and the Idaho Rules of Civil Procedure regarding appeals in Child Protective Act cases. A copy of the revisions can be found on the Court’s website at https://isc.idaho.gov/main/rules-for-public-comment. Please send your comments to Deena Layne, dlayne@idcourts.net by Thursday, October 5, 2023. Thank you.

Comments Sought on the Idaho Court Administrative Rules- Court Interpreters

The Idaho Supreme Court’s Language Access Committee is seeking input on proposed revisions to Idaho Court Administrative Rule 52, Court Interpreters. A copy of the revisions can be found on the Court’s website at https://isc.idaho.gov/main/rules-for-public-comment. Please send your comments to Deena Layne, dlayne@idcourts.net by Thursday, October 5, 2023. Thank you.

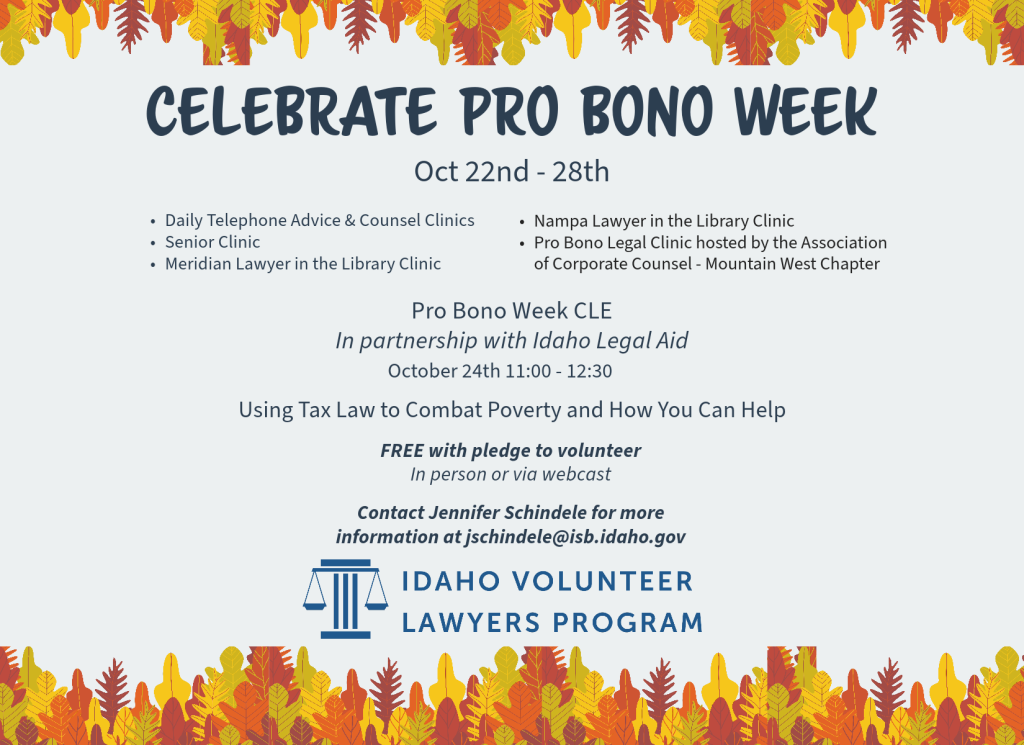

Celebrate Pro Bono Week October 22nd-27th!

Updated Mailing Address for Custer County

The mailing address for the Custer County Court has changed. The change is for the Court only, not the courthouse itself or any other offices.

Custer County Court

PO Box 1128

Challis, ID 83226

2023 Back to School CLE Bundle – Ends 9/29

2023 Back to School CLE Bundle

Limited Time Offer – September 5th through September 29th – 10 CLE credits (self-study) for only $150. Idaho Programs! Idaho MCLE Approved!

With the kids back in class it is a great time to sharpen your pencil too! The Idaho Law Foundation is offering the Back to School Bundle Package, which includes 10.0 CLE self-study credits for only $150! You will be given 90 days to make your program selections, with an additional 90 days following your selection to view each program. By selecting online, on-demand streaming, you will have the convenience to watch whenever and wherever you like!

Please Note: You will not be eligible to receive additional credit for the CLEs listed above you have attended or watched in the past. No refunds will be provided. No extensions will be awarded. All sales are final.

Your support of Idaho Law Foundation CLE programming provides the necessary resources to fulfill the Foundation’s goal of enriching the public’s understanding of and respect for the law and legal system. To take advantage of this great offer, select: 2023 Back to School Bundle.

*After you purchase your bundle, it is helpful to also have this list of courses up on a separate screen so that you can easily see the credits for each course to choose the 10.0 credits that you would like. Please contact our office with any questions.

- Millennials Rising: This Ain’t Your Parents’ Legal Profession (2022) – 1.5 CLE Credits

- Discrimination Based on Gender: Reconciling Bostock in a Rapidly Evolving Workplace (2022) – 1.0 CLE Credits

- Expert Disclosures: The Good, The Bad and The Ugly (2022) – 1.0 CLE Credits / NAC Approved

- From Alston to NIL to Future Employment? Recent Legal Developments in College Athletics Governance (2022) – 1.5 CLE Credits

- Promoting Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Belonging in Your Organization (2022) – 1.5 CLE Credits

- 2022 Lessons from the Masters (2022) – 1.5 CLE credits of which .5 are Ethics / NAC Approved

- Forensic Meteorology: Revealing Weather-Related Truths (2022) – 1.5 CLE Credits

- Recent Cases on Ethics and Common Questions to Bar Counsel (2022) – 1.5 CLE credits of which 1.5 are Ethics

- Appellate Mediation (2022) – 1.5 CLE credits / NAC Approved

- Bankruptcy for Beginners: The 10 Things EVERY Lawyer Should Know (2022) – 1.0 CLE Credits

- Introduction to Tribal Law (2022) – 1.0 CLE Credits

- Hog-Tight Fences and Dirk-Knives: Decoding Statutes from Idaho’s Infancy (2021) – 1.5 CLE credits / NAC Approved

- Handling Your First Appeal (2021) – 1.5 CLE credits / NAC Approved

- Local Rules Update and Practice Pointers (2021) – 1.5 CLE credits / NAC Approved

- 2021 Lessons from the Masters (2021) – 1.5 CLE credits of which .5 are Ethics / NAC Approved

- Internet Defamation (2021) – 1.5 CLE credits

- So, You’re Going to the United States Supreme Court – Now What? (2021) – 1.5 CLE credits

- Recalibrating Your Law Practice for the Evolving Cybersecurity Threats (2021) – 1.5 Ethics credits / NAC Approved

- The History of Idaho in the Ninth Circuit (2021) – 1.5 CLE credits

- Emerging Issues in the Trademark Law and Unfair Competition (2021) – 1.5 CLE credits

- The Climate of Civility and Professionalism in the Practice of Law in Idaho (2021) – 2.0 Ethics credits / NAC Approved

- 2020 Lessons from the Masters (2020) – 1.5 CLE credits of which .5 are Ethics

- Ethical Guidance for Cyber-Crime Prevention and Response (2020) – 1.5 CLE credits of which 1.5 are Ethics

- Violence in the Legal Profession: A Study of Idaho and our Colleagues Nationwide (2020) – 1.5 CLE credits

- Ten Things All Idaho Lawyers Should Know About Indian Law and Business or Murder? The U.S. Supreme Court and Herrera v. Wyoming (2020) – 1.5 CLE credits

- The Life Cycle of an Estate Plan: Understanding Estate Planning Strategies and Use of Basic Wills and Trusts (2020) – 2.0 CLE credits 1.0 / NAC Approved

- Con Law by the Numbers (2020) – 2.0 CLE credits

- Lawyer Well-Being: What’s It Got to Do with Me? (2020) – 1.5 CLE credits

- Holistic Trial Work: Viewing Your Case with an Eye Towards Appeal and Viewing Your Appeal with an Eye Toward Remand (2020) – 1.5 CLE credits / NAC Approved

- Social Media & Ethics (2020) – 1.5 CLE credits of which 1.5 are Ethics

- Understanding and Representing Clients Who’ve Experienced Trauma in Family Law Matters – What You Need to Know About Trauma (2020) – 1.5 CLE credits

- Clearing Barriers to Military Legal Readiness (2019) – 1.5 CLE credits of which .75 are Ethics

- A View From the Appellate Bench in Idaho (2019) – 1.5 CLE credits of which 1.5 / NAC Approved

- 2019 Lessons from the Masters (2019) – 1.5 CLE credits of which .5 is Ethics credits / NAC Approved

- Technology and a New Generation: How Progress Affects Professional Responsibility (2019) – 2.0 Ethics credits / NAC Approved

- Can I Get This Tweet Admitted? Evidentiary Issues in the Digital Age (2019) – 2.0 CLE credits / NAC Approved

Recap of 2023 Idaho State Bar Annual Meeting

By Teresa A. Baker

The 2023 Idaho State Bar Annual Meeting was held in Boise at Jack’s Urban Meeting Place (“JUMP”) from July 19th through the 21st.

The meeting kicked off with the Distinguished Lawyer, Distinguished Jurist, and Outstanding Young Lawyer Awards Reception on Wednesday evening. The awards ceremony began with President Laird B. Stone serving as the Master of Ceremonies with over 150 guests in attendance. The recipients of the 2023 Distinguished Lawyer Awards were Larry C. Hunter of Boise and Marvin M. Smith of Idaho Falls. The Distinguished Jurist Award was presented to the Honorable Roger S. Burdick, former Chief Justice of the Idaho Supreme Court. The Outstanding Young Lawyer Award was presented to Ashley R. Marelius of Boise. Each award recipient was introduced with a short video of an interview by a colleague or friend and then each graciously accepted their award at the podium. Ms. Marelius’ award was accepted by her law partners, as she was unable to be in attendance.

Thursday morning, July 20th, began with a Plenary Session in which President Stone gave an update on the state of the Bar and Idaho Supreme Court Chief Justice G. Richard Bevan gave an update on the state of the Idaho Courts. President Stone then introduced the keynote speaker, Jerry V. Teplitz, J.D., Ph.D. Dr. Teplitz spoke on the importance of attorney well-being and gave participants techniques and tools to increase their level of energy and productivity to better serve clients and themselves. A total of 5.5 CLE credits were offered on Thursday with two different breakout sessions offered. The late afternoon CLE session featured a session entitled “Preserving Independence, Impartiality, and Excellence in Idaho’s Court System: A Remarkable Judiciary, If You Can Keep It,” and featured a distinguished panel that was moderated by Idaho State Bar Commissioner Mary V. York. The panel included Justice Jim Jones, Former Chief Justice of the Idaho Supreme Court, Hon. Karen L. Lansing, retired member of the Idaho Court of Appeals, J. Philip Reberger, Idaho Judicial Council, and Donald L. Burnett, Jr., Dean Emeritus at the University of Idaho College of Law and an inaugural member of the Idaho Court of Appeals. The session was informative and thought-provoking for all.

During a Noon luncheon, the Idaho State Bar and Idaho Law Foundation Service Awards were presented with over 125 people in attendance. Seven lawyers from around the Gem State who have provided volunteer time to support the work of the Bar and the Law Foundation were honored including:

Mia Bautista of Moscow, Charles “Clay” Gill and Emily MacMaster of Boise, Casey Simmons of Coeur d’Alene, Brent T. Wilson of Salt Lake City, along with Debbie Dudley, the recently retired controller of the Idaho State Bar. Howard Burnett of Pocatello and William “Bill” McAdam of Sandpoint were also honored but were unable to attend. When the awards program concluded the Idaho Law Foundation held their Annual Meeting led by President Fonda L. Jovick of Sandpoint.

The Milestone Celebration and Awards Reception: Celebrating 25, 40, 50, 60 & 65 Years of Admission was held Thursday evening with over 130 people in attendance. The longest admitted member of the Bar in attendance was William Parsons, a 65-year member and was joined by 60-year attorneys Tony Park and Hon. Jesse Walters. The 50-year attorneys in attendance included Darrel Aherin, Ron Bruce, Linda Cook, Don Farley, James “Jim” Kaufman, Doug Nelson, Jerry Reynolds, Milton Slavin, Paul Street, Ron Twilegar, Cindy Weiss, and Hon. William Woodland. Each of these attorneys were presented with a plaque and each gave a highlight of their career. The 40- and 25-year attorneys were also honored with lapel pins for their attendance and dedication to the profession.

On Friday, July 21st an additional 4.5 CLE credits were offered to conference participants with two sets of CLE breakout sessions and the final plenary session. This year, the annual “Lessons from the Masters” was called “Lessons from the Bench” and featured Justice Colleen D. Zahn, Idaho Supreme Court, Hon. Debora K. Grasham, U.S. Magistrate, District of Idaho, and Hon. Nancy A. Baskin, Fourth Judicial District.

At Noon a networking BBQ was held with the Section of the Year Award presented to the members of the Employment and Labor Law Section. President Stone then passed the gavel to incoming President Gary L. Cooper who will serve as president until the next Annual Meeting in 2024. Lastly, the door prizes from our exhibitors were drawn from the meeting attendees who visited the exhibit hall.

The Annual Meeting would not be possible without the support of our sponsors. This year’s sponsors included platinum sponsors Idaho Trust Bank and the Fourth District Bar Association, gold sponsors University of Idaho College of Law and Clio, silver sponsors River’s Edge Mediation and the Idaho Community Foundation, and bronze sponsor Eagle Creek Recovery.

The Great Salt Lake and Idaho

By James R. Cefalo

In recent years, there have been numerous news articles about the causes and impacts of declining water levels in the Great Salt Lake. Idahoans may feel that Great Salt Lake water levels are Utah’s problem. Idaho does, however, have an interest in the Great Salt Lake, because the lake is fed by streams that arise in or flow through Idaho. This article contends that Idahoans should become familiar with the Great Salt Lake issues and monitor the actions the federal government and the State of Utah are taking to address the decline in lake levels. This article provides some basic facts about the Great Salt Lake and its relationship to the Bear River. Additionally, it describes how changes in laws, regulations, and policies related to the Great Salt Lake could affect water users in Idaho, particularly those water users located in the Bear River Basin. The State of Idaho and its water users in the Bear River Basin should carefully monitor the actions intended to restore the Great Salt Lake to ensure those actions do not negatively impact water users in Idaho.

Great Salt Lake Basics

The Great Salt Lake is a terminal lake, meaning it has no natural outlet to the ocean.[i] It is the largest saline lake in the Western Hemisphere.[ii] The major tributaries to the Great Salt Lake are the Jordan River, which collects water from rivers and streams in the mountains surrounding Salt Lake City and Provo, the Weber River, and the Bear River.[iii] Of these three rivers, the Bear River is the largest tributary, accounting for approximately 60% of the freshwater entering the lake each year.[iv]

Water levels in the Great Salt Lake have been regularly monitored since the pioneers entered the Salt Lake Valley in the mid-1800s.[v] In 1986, the lake reached a historic maximum level at an elevation of 4,211.7 feet above sea level.[vi] At that level, the surface area of the lake is over 3,300 square miles.[vii] In November 2022, the lake reached a historic low at an elevation of 4,188.6 feet above sea level, roughly 23 feet lower than the high point in 1986.[viii] At the historic low water level, the surface area of the lake is only 950 square miles.[ix] To conserve water and prevent evaporation, the State of Utah has blocked off channels to the north arm of the lake, significantly reducing the active surface area of the lake.[x]

Bear River Basics

The Bear River is an interstate stream that flows through the southeast corner of Idaho.[xi] Its headwaters are in the Uinta Mountains in Utah.[xii] The Bear River flows from Utah into Wyoming, near Evanston, then back into Utah, then back into Wyoming, then flows into Idaho just east of Montpelier.[xiii] The Bear River flows north from Montpelier to Soda Springs, then turns south and flows past the communities of Grace and Preston before flowing back into Utah north of Logan, Utah.[xiv] The river flows into the Great Salt Lake on the east side of the lake, just west of Brigham City, Utah.[xv] Although the Bear River is over 500 miles long, it empties into the Great Salt Lake just 90 miles from its headwaters.[xvi]

In Idaho, the Bear River is primarily diverted for direct irrigation use. It is also diverted to fill Bear Lake, an augmented natural lake that also serves as a storage reservoir for downstream irrigators. Water users in Wyoming and Utah also divert water from the Bear River and its tributaries, primarily for irrigation use.[xvii]

In 1958, Idaho, Utah, and Wyoming adopted the Bear River Compact to resolve disputes about water deliveries in the Bear River Basin.[xviii] The Compact was amended in 1980 to include provisions about future water development within the basin.[xix] The Amended Compact has many fascinating nuances that could entertain a water law attorney for hours. For purposes of this article, however, it is sufficient to note that Idaho participates in a federally approved interstate compact which addresses water deliveries on the Bear River during times of shortage and governs future development of water resources within the river system.

Although the Amended Compact describes a process to initiate formal administration of water rights by priority date in the Lower Division (which extends from Bear Lake to the Great Salt Lake), the states of Utah and Idaho have voluntarily administered water rights in the Lower Division without regard to the Idaho-Utah state line. In other words, water rights on the main channel of the Bear River between Bear Lake and the Great Salt Lake are currently regulated against a common priority date.

Bear River Diversions and Great Salt Lake Levels

Some advocates for restoring the Great Salt Lake contend that the recent decline in lake levels is caused by an increase in diversions by upstream farmers and ranchers, particularly in the Bear River Basin. This contention fails to consider important nuances of water use in the Bear River Basin and is often presented as an attack on irrigators.

Water has been diverted from the Bear River and its tributaries for irrigation use since the late 1800s. In Idaho, many of the water rights for irrigation use from the Bear River or its tributaries bear priority dates senior to 1900, meaning the water rights were developed prior to 1900 and have been used for irrigation since the rights were first developed. In drought years, like 2021 and 2022, because of a limited surface water supply, the only water rights from the Bear River and its tributaries receiving water through most of the summer are those rights with priority dates senior to 1900. In drought years, junior water rights (those with priority dates later than 1900) on the Bear River and its surface water tributaries have little impact on water levels in the Great Salt Lake because those water rights receive little or no water.

As part of the 1980 Amended Compact, the states of Idaho, Utah, and Wyoming agreed to track future depletions in the Bear River Basin.[xx] In April 2023, the Bear River Commission approved a report summarizing the depletions occurring in the Bear River Basin since 1976.[xxi] According to the report, since 1976, there have been only 14,410 acre-feet of additional depletions developed above Stewart Dam (located near Montpelier, Idaho) and only 11,307 acre-feet of additional depletions developed between Stewart Dam and the Great Salt Lake.[xxii] In total, the water developments occurring after 1976 only consume approximately 26,000 acre-feet of water. To put that number into perspective, at the historic low water level in November 2022, the Great Salt Lake contained approximately 4.5 million acre-feet of water.[xxiii]

The 2023 report shows there have been very minor changes to the annual depletions occurring in the Bear River Basin since 1976. In fact, in some areas of the basin, total depletions are lower today than in 1976.[xxiv] The Great Salt Lake hit its maximum recorded lake level in 1986. The total water use from the Bear River has only slightly increased since 1986, yet the lake levels have declined dramatically. What has changed? The answer is simple: snowpack, or lack thereof. Between 1982 and 1986 (the historical maximum lake level), the Bear River Basin had consecutive years of above-average snowpack. In the 10 years prior to 2023, the Bear River Basin had only one year with snowpack significantly above the average (2017), four years with near average snowpack (2014, 2016, 2019, and 2020), and five years of below average snowpack (2013, 2015, 2018, 2021, and 2022).[xxv]

To a large extent, the use of surface water in the Bear River drainage has remained steady for nearly 150 years, particularly in drought years, when junior rights are curtailed. Despite this steady historical irrigation use, the Great Salt Lake reached a maximum recorded lake level in 1986. Although water users in the Bear River Basin have some impact on lake levels, it seems unfair to solely blame those water users for the current woes of the Great Salt Lake.

Future Development in the Bear River Basin

It is important to note that the opportunities for additional water development in the Bear River Basin in Idaho are quite limited. In Idaho, the Bear River and its tributaries have been considered fully appropriated during the irrigation season since the early 1980s. In 2001, the Bear River Basin in Idaho was designated as a Ground Water Management Area (“GWMA”), pursuant to Idaho Code § 42-233b. As such, the depletions (consumptive use) associated with new ground water uses (except for small domestic and stock water uses) must be fully mitigated by commensurate reductions in consumptive use.

The Malad River originates in Idaho and flows into the Bear River in Utah. In November 2015, the Idaho Department of Water Resources issued a moratorium on new appropriations from ground water in Malad Valley. Like the Bear River GWMA, new consumptive uses of ground water in Malad Valley (except for small domestic and stock water uses) must be fully mitigated.

Utah has taken similar steps to restrict future development in the Bear River Basin in Utah. Because of concerns about Great Salt Lake levels, on November 3, 2022, Governor Cox of Utah issued Proclamation No. 2022-01, suspending the appropriation of the surplus and unappropriated water of the Great Salt Lake and its tributaries, including the Bear River.[xxvi] The proclamation does not have a specific term or sunset provision but does call for the State Engineer to prepare a report evaluating whether the proclamation should remain in effect.[xxvii]

Federal Action

The federal government is also acting on Great Salt Lake concerns. In December 2022, President Biden signed the Saline Lake Ecosystems in the Great Basin States Program Act of 2022, which authorizes the United States Geological Society (“USGS”) to create a program “to assess and monitor the hydrology of saline lake ecosystems in the Great Basin,” including the Great Salt Lake.[xxviii] The USGS will work with Tribal, Federal, and State agencies, nonprofit organizations, universities, and local stakeholders to prepare a report describing specific actions needed to improve data collection for the assessment of saline lakes in the West.[xxix] The act allocates $25 million over five years to complete the report and implement the assessment and monitoring programs.[xxx] Of note, the act states that it shall have no effect on existing water rights, interstate compacts, or the management and operation of Bear Lake.[xxxi]

“Saved Water” for the Great Salt Lake

On March 14, 2023, Governor Cox of Utah signed S.B. 277, which significantly revised Utah’s laws related to water conservation. S.B. 277 creates an “agricultural water optimization” program, which allows Utah irrigators to apply for grants to install water conservation infrastructure. The statute identifies the water conserved through these infrastructure projects as “saved water.” In addition, S.B. 277 describes a process by which a water user in Utah can file a change application (transfer application) to designate a portion of their water right as “saved water.” The saved water can then be sold or leased to others and possibly sold or leased to the State of Utah to increase water levels in the Great Salt Lake.[xxxii] Moving saved water to a new location or dedicating the saved water to a new use raises concerns about injury to other water users and enlargement of use. The following hypothetical illustrates these concerns.

Assume Farmer Stewart diverts water from Canyon Creek. Also assume Stewart’s existing irrigation system is fairly inefficient – open ditches and flood irrigation. Although Stewart diverts 10 cubic feet per second (cfs) of water, his crops only consume about 60% (6 cfs) of the water. The remaining 40% (4 cfs) returns to Canyon Creek, either on the surface or subsurface, and is used to satisfy downstream water rights. Assume Stewart now installs pipelines and a drip irrigation system to become more efficient. Stewart’s crops continue to consume about 6 cfs, but now Stewart only diverts 6 cfs because his system is so efficient. The remaining (undiverted) 4 cfs is “saved water.” If the 4 cfs is simply left in the creek, it could still be used to satisfy downstream water rights. If, on the other hand, Stewart is allowed to sell or lease the 4 cfs to another water user or dedicate the 4 cfs to lake recovery, the 4 cfs is no longer available to satisfy downstream water rights. To satisfy downstream water rights (that used to rely on the 4 cfs of return flow from Stewart), upstream junior water rights (possibly junior water rights in other states) would have to be curtailed to replace the 4 cfs of saved water sold or leased by Stewart.

In Idaho, a water user may convey all or a portion of a water right to another person. Idaho Code § 42-222(1) states that this type of conveyance can be approved, provided the change does not injure other water rights or result in an enlargement of use under the original right. To protect against injury and enlargement, when a water user proposes to change the nature of use of a water right, such as from irrigation to municipal use, the State of Idaho limits the new use to the consumptive portion of the water right to be changed. Statutes governing change applications in Utah contain similar protections against injury and enlargement.[xxxiii]

It is unclear whether S.B. 277 revises Utah’s protections against injury and enlargement for change applications involving saved water. S.B. 277 distinguishes between “depletion reduction,” which means a “net decrease in water consumed,” and “diversion reduction,” which means a “decrease in the net diversion amount from that allowed under a water right.”[xxxiv] In one section, S.B. 277 suggests that water users will only be able to convert depletion reductions from irrigation use to “saved water.”[xxxv] In other areas, however, S.B. 277 states that “saved water” is comprised of depletion reductions and diversion reductions.[xxxvi] This is a critical question. If “saved water” includes diversion reductions and can now be dedicated to fully consumptive uses, like Great Salt Lake restoration, there could be significant injury and enlargement impacts for upstream water users, including water users in Idaho.

The Great Salt Lake is a unique and valuable ecosystem and Utah’s efforts to restore and preserve the lake are commendable. These restoration and preservation efforts, however, cannot come at the expense of water rights or water users in Idaho. Over the coming years, as Utah begins to apply S.B. 277, Idahoans must pay close attention to how the water conservation program is implemented to ensure that changes involving “saved water” do not shift impacts to water users in Idaho.

James R. Cefalo is the Eastern Regional Manager for the Idaho Department of Water Resources (“IDWR”). He received a bachelor’s degree in civil in environmental engineering from the University of Utah and a J.D. from the University of Colorado. James was born and raised in Brigham City, Utah, which lies just east of the Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge. The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s and are not the opinions or positions of IDWR or the State of Idaho.

[i] Wayne Wurtsbaugh, Craig Miller, Sarah Null, Peter Wilcock, Maura Hahnenberger, Frank Howe, Impacts of Water Development on Great Salt Lake and the Wasatch Front, Watershed Sciences Faculty Publications (Feb. 24, 2015).

[ii] Great Salt Lake, Utah Division of Water Resources,https://water.utah.gov/great-salt-lake/.

[iii] Wurtsbaugh, supra note 1, at 1.

[iv] Id.

[v] Great Salt Lake, supra note 1.

[vi] Id.

[vii] Id.

[viii] Id.

[ix] Id.

[x] Great Salt Lake, supra note 1; Utah Exec. Order 2023-02 (Feb. 23, 2023) (ordering the Utah Division of Forestry, Fire, and State Lands to raise the berm around the causeway bridge, which spans the channel connecting the North Arm of the Great Salt Lake to the main body of the lake, to 4,192 feet above sea level); see also Ben Winslow, Water now spilling over emergency causeway berm in the Great Salt Lake, Fox 13 News, https://www.sltrib.com/news/2023/05/03/water-now-spilling-over-emergency/ (reporting that water was spilling over the emergency berm in May 2023 because of increased lake levels).

[xi] https://bearrivercommission.org/docs/Bear%20River%20Basin%20Map-goodscan.pdf (diagram of Bear River Basin prepared by the Bear River Commission).

[xii] Id.

[xiii] Id.

[xiv] Id.

[xv] Id.

[xvi] The Bear River, Wyoming State Water Plan, Wyoming Water Development Office, https://waterplan.state.wy.us/BAG/bear/briefbook/bcompact.html.

[xvii] Id. (Between Idaho, Utah, and Wyoming, over 500,000 acres are irrigated from the Bear River and its tributaries).

[xviii] The Bear River Commission, an entity created through the Bear River Compact, prepared an excellent report of the disputes and negotiations leading up to the ratification of the 1958 Compact and the 1980 Amended Compact. The report, written by Wallace N. Jibson and titled “History of the Bear River Compact,” can be found on the commission’s website: https://bearrivercommission.org/docs/History%20of%20Bear%20River%20Compact.pdf.

[xix] I.C. § 42-3402, Article V.

[xx] I.C. § 42-3402, Article V(C).

[xxi] 2019 Depletions Update (April 18, 2023) at 2. The 2019 Depletions Update is a report prepared by the Technical Advisory Committee for the Bear River Commission and does not identify authors by name. It was adopted by the commission at its annual meeting on April 18, 2023.

[xxii] Id. An acre-foot of water is a measurement of volume, one foot deep covering one acre, and is equal to 325,850 gallons of water.

[xxiii] See Robert L. Baskin, Calculation of Area and Volume for the South Part of the Great Salt Lake, United States Geological Survey (2005), https://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2005/1327/PDF/OFR2005-1327.pdf.

[xxiv] 2019 Depletions Update (April 18, 2023) at 2 (Utah’s depletions downstream of the Idaho-Utah state line are 5,336 acre-feet less today than in 1976).

[xxv] https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/Internet/WCIS/AWS_PLOTS/basinCharts/POR/WTEQ/assocHUCut_8/bear.html (displaying annual snowpack data collected by the U.S. Natural Resources Conservation Service).

[xxvi] Utah Proclamation 2022-01, Utah Code § 73-61 (Nov. 3, 2022). The proclamation restrictions do not apply to non-consumptive uses or appropriations of small amounts of water. Id.

[xxvii] Id.

[xxviii] Pub. L. No. 117-318, 136 Stat. 4421 (2002).

[xxix] Id.

[xxx] Id.

[xxxi] Id.

[xxxii] Amy Joi O-Donoghue, Shift in Utah Water Law could be “Game changer’ for the Great Salt Lake, Deseret News (March 7, 2023).

[xxxiii] Utah Code § 73-3-3(1)(e).

[xxxiv] Utah Code § 73-10g-203.5(7) and (8).

[xxxv] Utah Code § 73-10g-208(1)(a).

[xxxvi] Utah Code §§ 73-10g-203.5(10), 73-10g-208(2).

Sackett v. EPA: North Idaho’s Clean Water Act Wild Card[i]

By Norman M. Semanko

The Clean Water Act (“the Act”) has become fertile ground for extensive litigation in the federal courts. And no issue has been more prominent than the Act’s jurisdictional trigger term, “navigable waters,” defined in the Act simply as “the waters of the United States” (“WOTUS”).[ii] This determines whether projects and other activities require federal permits to discharge into, dredge, or fill waters.[iii] The most recent addition to this series of cases, Sackett v. Env’t Prot. Agency,[iv] provides an updated definition of WOTUS and comes to us from Bonner County. This article provides a brief background of the litigation before Sackett, the route by which Sackett arrived at the Supreme Court of the United States, the Court’s updated definition of WOTUS as provided in Sackett’s majority opinion, and some thoughts on what comes after Sackett.

Setting the Stage for Sackett

For 50 years, the question of what constitutes “the waters of the United States” was left to the Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”) and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to determine through rulemaking and associated guidance and manuals. While the U.S. Supreme Court came tantalizingly close to announcing a WOTUS test in Rapanos v. United States,[v] it ultimately failed to deliver a majority opinion in that case.

In Rapanos, a plurality opinion of four Justices, authored by Justice Scalia, concluded that “waters” encompasses “only those relatively permanent, standing or continuously flowing bodies of water ‘forming geographic[al] features’ that are described in ordinary parlance as ‘streams, oceans, rivers, and lakes.’”[vi] Under the plurality test, “the waters of the United States” are relatively permanent bodies of water connected to traditional interstate navigable waters through a continuous surface connection.[vii] One Justice concurred with the plurality in the result (that wetlands near ditches and drains that eventually emptied into navigable waters at least 11 miles away were not jurisdictional under the Act) – but not in its reasoning. This broader interpretation of jurisdiction under the Act found that “the waters of the United States” include those waters and adjacent wetlands that possess a “significant nexus” to traditional navigable waters.[viii]

Since Rapanos, the scope of “navigable waters” has gone back and forth – expanding and contracting – thereby resembling a game of ping pong between different Presidential Administrations.[ix] All of that changed with the U.S. Supreme Court’s May 25, 2023 ruling in Sackett v. EPA.[x]Interestingly enough, the story begins and ends in North Idaho.

The Sacketts’ Route to the Supreme Court

Michael and Chantell Sackett own a small piece of property near Priest Lake, in Bonner County, Idaho. The Sacketts wanted to build a home on their lot and began to fill it with dirt and rocks in preparation for the construction. The EPA stepped in and issued a compliance order to the Sacketts, threatening civil penalties of approximately $40,000 per day and informing them that their activities violated the Act because their property contained jurisdictional wetlands. The Sacketts maintained that the EPA had no jurisdiction over their property under the Act.[xi]

After several years of proceedings, the U.S. District Court entered summary judgment for the EPA and the Ninth Circuit affirmed, holding that the Act covers adjacent wetlands with a significant nexus to traditional navigable waters and that the Sacketts’ lot satisfied that standard.[xii] The Supreme Court granted certiorari to decide the proper test for determining whether wetlands are “waters of the United States.”[xiii]

At the time that Sackett was under consideration in the Ninth Circuit, litigation brought in numerous federal district courts by states and various groups, challenging the regulatory definition of WOTUS, was calculated to result in the issue ultimately being taken up by the U.S. Supreme Court. As predicted, however, Sackett proved to be the wild card that actually made it to the Supreme Court.[xiv]

The Sackett Majority Opinion Explained

Justice Alito delivered the opinion of the Court on behalf of a majority of five Justices.[xv] The Court held that the Act only applies to wetlands that have a “continuous surface connection” with “waters of the United States.”[xvi] In doing so, the opinion expressly adopted Justice Scalia’s plurality opinion from Rapanos. It also rejected Justice Kennedy’s “significant nexus” test.[xvii]

The Sackett majority opinion adopted Justice Scalia’s Rapanos conclusion that “waters” in the Act encompasses “only those relatively permanent, standing or continuously flowing bodies of water forming geographic[al] features that are described in ordinary parlance as streams, oceans, rivers, and lakes,” also referred to as “traditional navigable waters.”[xviii] Further, the opinion concluded that wetlands are included within “waters of the United States” and must therefore “qualify as waters of the United States in their own right.” The wetlands must be “indistinguishably part of a body of water that itself constitutes waters of the United States.”[xix] As the plurality stated in Rapanos, the term “waters” in the Act “may fairly be read to include only those wetlands that are as a practical matter indistinguishable from waters of the United States, such that it is difficult to determine where the ‘water’ ends and the ‘wetland’ begins.”[xx] Such “indistinguishability” only “occurs when wetlands have a continuous surface connection to bodies that are waters of the United States in their own right so that there is no clear demarcation between ‘waters’ and wetlands. […] Wetlands that are separate from traditional navigable waters cannot be considered part of those waters, even if they are located nearby.”[xxi]

What’s Next?

Even with the Sackett majority opinion now firmly in place, litigation is sure to continue, including ongoing challenges to the Biden Administration’s WOTUS Rule,[xxii] which is underpinned by the now defunct “significant nexus” test.[xxiii] Already, the Biden Rule has been stayed in 27 states – including Idaho – while the federal courts ultimately proceed to determine its validity under the Act.[xxiv] Idaho and Texas have jointly filed a motion for summary judgment, seeking to strike down the Biden WOTUS Rule in its entirety as being in violation of the Supreme Court’s holding in Sackett.[xxv]

In the meantime, the Biden Administration has indicated that it will revise its existing WOTUS Rule no later than September 1, 2023, in an attempt to conform to the Supreme Court’s decision in Sackett.[xxvi] This move may also be susceptible to legal challenges, depending upon how the rule change is accomplished – with or without notice and an opportunity for public comment – and whether it is successful in actually adhering to the Court’s pronouncements in Sackett.

Whether the game of regulatory ping pong is over or not, Sackett proved itself as the wild card in what turned out to be a winning hand before the U.S. Supreme Court.

Norman M. Semanko is the Managing Shareholder in the Boise office of Parsons, Behle & Latimer. His practice includes a variety of natural resource and environmental law matters, with a particular emphasis on water. He readily admits to occasionally playing penny-ante poker (yes, the joker is a wild card) while growing up in North Idaho.

[i] A wild card is “an unknown or unpredictable factor” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/wild%20card. Accessed 6 Jul. 2023.

[ii] 33 U.S.C. § 1362(7).

[iii] 33 U.S.C. §§ 1342, 1344.

[iv] 143 S. Ct. 1322 (2023).

[v] 547 U.S. 715 (2006).

[vi] 547 U.S. at 739 (plurality opinion).

[vii] 547 U.S. at 742, 755 (plurality opinion).

[viii] 547 U.S. at 759, 779-780 (opinion of Kennedy, J.).

[ix] Norman M. Semanko, Red Paddle-Blue Paddle: Clean Water Act Ping Pong, 64 Advocate 22 (2021).

[x] 598 U.S. ___, 143 S.Ct. 1322 (2023).

[xi] See generally, Sackett v. EPA, 566 U.S. 120 (2012) (also known as “Sackett I” to distinguish it from the 2023 case) (holding that EPA compliance order was final agency action and therefore subject to review under the APA).

[xii] 8 F.4th 1075, 1091-93 (2021).

[xiii] 595 U.S. ___ (2022).

[xiv] 64 Advocate 22 (2021).

[xv] The Ninth Circuit’s decision was reversed and remanded, 9-0. In addition to Justice Alito’s majority opinion, concurring opinions were penned by Justices Thomas, Kagan, and Kavanaugh.

[xvi] 143 S.Ct. at 1322.

[xvii] Id. at 1341-43.

[xviii] Id. at 1336-37 (citing 547 U.S. at 739).

[xix] Id. at 1339.

[xx] 547 U.S. at 742.

[xxi] 143 S.Ct. at 1340.

[xxii] 88 Fed. Reg. 3004 (2023).

[xxiii] Id. at 3006, 3143.

[xxiv] https://www.epa.gov/wotus/definition-waters-united-states-rule-status-and-litigation-update (accessed July 6, 2023).

[xxv] States’ Motion for Summary Judgment, Case No. 3:23-cv-00017 (S.D. Tex. June 28, 2023).

[xxvi] https://www.epa.gov/wotus/amendments-2023-rule (accessed July 6, 2023).

Curtailing Water Use in a Good Water Year?

By Meghan M. Carter

No doubt many of you have seen these or similar headlines this spring: “Possible Water Curtailments Even in a Good Year”[i] and “New Idaho Department of Water Resources Order Would Force 900 Groundwater Users to Curtail Use.”[ii] These news stories were in response to an order issued by the Idaho Department of Water Resources (“Department”) in April. The order outlines the updated methodology the Department uses to determine injury to surface water users in the Eastern Snake Plain by groundwater users diverting water from the Eastern Snake Plain Aquifer.[iii]

Understanding what the headlines mean can stump even a seasoned water law attorney. Fear not, in this article I will provide some history, terminology, and summaries of where things stand today with water use on the Eastern Snake Plain.

The Eastern Snake Plain Aquifer

This spring’s headlines are rooted in the history of water use on the Eastern Snake Plain and the hydrologic connection between surface water and the Eastern Snake Plain Aquifer (“ESPA”). Surface water percolates through the ground to the ESPA which underlies some 10,800 square miles of southern Idaho.[iv] The ESPA has a strong hydrologic connection to the Snake River, and it discharges to the Snake River through gaining reaches and springs. Most natural inputs to the ESPA come from mountain runoff. However, incidental recharge from irrigation practices on the Eastern Snake Plain in the early 20th Century massively and artificially increased ESPA water levels and subsequently increased discharge to the Snake River.[v]

In the early 1950s, irrigation practices started to change. Sprinkler irrigation began to be favored over flood irrigation, and demand for water increased. In addition, pumping technology and cheaper energy prices lead to increased groundwater pumping. These trends paired with a series of droughts resulted in reduced water recharge to the aquifer, greater groundwater extraction from the aquifer, and a steady decline in the volume of water in the ESPA.[vi]

Following a three-year downtrend in aquifer levels, Department data shows that 2023’s aquifer levels are approaching the lowest since the 1950s.[vii] These declines are occurring despite above-average snowpack in the mountains feeding the ESPA this year.[viii]

Interlude for Some Water Law

Idaho is a prior appropriation state, meaning the first (senior) use of water takes priority over subsequent (junior) uses of that same water.[ix] This is a harsh legal doctrine that does not place a value on the type of water use. Nor does prior appropriation allow for the reduction of water use across all water users. Instead, the senior user’s water right is fully met before junior users can take any water.

The process the Department uses to administer water rights in priority is called water rights administration. If a senior water use is not being met, the water user can file a delivery call with the Department. A delivery call is a request for water rights administration seeking to have the Department ensure senior water uses are met before junior water uses.[x] Once a delivery call is filed, the Department determines whether the senior water use is being materially injured and if so, which junior water rights should be curtailed.

Idaho administers groundwater and surface water conjunctively. This means if there is a known and legally recognized hydraulic connection between groundwater and surface water, they are administered together in priority.[xi] The Department uses a groundwater model, the Eastern Snake Plain Aquifer Model (“ESPAM”), to help conjunctively administer water use on the Eastern Snake Plain. ESPAM models groundwater inputs and outputs throughout the ESPA based on differing weather and irrigation practices. The effort to develop ESPAM started in 2000.[xii] Version 1.1 was used between 2005 and early 2012. Version 2.1 was used thereafter until Version 2.2, was released in 2021.[xiii]

Because surface water use was generally developed before groundwater use, many groundwater rights are junior to surface water rights. The dynamic has resulted in fierce conflict between surface and groundwater users in the Eastern Snake Plain.

The Surface Water Coalition Delivery Call

In 2005, conflict between surface and groundwater users over reduced availability of surface water came to a head. A group of surface water irrigation entities, known as the Surface Water Coalition (“Coalition”) filed a delivery call with the Department, asking for the Department to curtail junior groundwater use to ensure adequate water supply for senior surface water users.[xiv]

The Coalition’s delivery call alleged that “data collected by the United States Bureau of Reclamation over the past six years indicates an approximate 30% reduction in reach gains to the Snake River between Blackfoot and Neeley, a loss of about 600,000 acre-feet.”[xv] Further, “[t]he recently recalibrated ESPA groundwater model identifies groundwater pumping as a major contributor to declines in the source of water fulfilling senior surface water rights.”[xvi]

The Director of the Department issued an interlocutory order within a month of the Coalition’s delivery call,[xvii] amending or supplementing the order several times, ultimately issuing his seventh supplemental order in 2007.[xviii] A hearing was held in 2008.[xix]

After the hearing, the Director issued an order, concluding that “[g]round water pumping has hindered [Coalition] members in the use of their water rights by diverting water that would otherwise go to fulfill natural flow or storage rights.”[xx] However, he ultimately determined that “junior groundwater users could continue to divert if they provided water in the amount of predicted shortage to members of the SWC that were attributable to their depletions.”[xxi]

The Director also concluded that “requiring curtailment to reach beyond the next irrigation season involves too many variables and too great a likelihood of irrigation water being lost […] .”[xxii] Therefore, the Director held that ongoing administration is needed, which brings us to the “Methodology Order” and its subsequent amendments through 2023.[xxiii]

The Methodology Orders

Because the Coalition’s water supply varies from year to year, ongoing administration requires a yearly evaluation of water availability and water need. That yearly evaluation is outlined in what is known as the Methodology Order, first issued in 2010 (and amended numerous times since). The Methodology Order is “a single, cohesive document by which the Director will quantify material injury in terms of reasonable in-season demand and reasonable carryover.”[xxiv]

The terms “material injury,” reasonable in-season demand (“RISD”), and “reasonable carryover” represent key concepts in the Methodology Order. “Material Injury” is defined as “[h]inderance to or impact upon the exercise of a water right caused by the use of water by another person as determined in accordance with Idaho law […].”[xxv] A determination of material injury depends upon a number of factors, including the amount of water available from the senior’s water source, the efficiency of the senior’s water system, and the availability of alternative points of diversion for the senior’s water rights.[xxvi] RISD is the projected volume of water needed during the relevant evaluation year to grow crops within each entity’s service area.[xxvii] The RISD is calculated using historic demands of a baseline year or years (“BLY”) as “corrected during the season to account for variations in climate and water supply between the BLY and actual conditions.”[xxviii] Reasonable carryover is “the difference between a baseline year demand and projected typical dry year supply.”[xxix]

The Methodology Order outlines nine steps for making a material injury determination each year. The steps can be summarized as follows. In April, the Department makes a prediction of how the demand for the upcoming irrigation season compares to the previous year’s carryover. If there is a predicted shortage, groundwater users must demonstrate “their ability to secure and provide a volume of storage water or to conduct other approved mitigation activities that will provide water to the injured members of the [Coalition].”[xxx] Next, during the mid-irrigation season (usually in July), the Department will evaluate actual crop water needs, issue a revised forecast of supply, and establish when groundwater users must provide the Coalition with water that year.[xxxi] At the end of the irrigation season, the Department determines the amount of carryover water that is owed to the Coalition.[xxxii]

The process outlined in the Methodology Order allows the Department to timely administer water rights in the Eastern Snake Plain so that the Coalition does not suffer material injury to its water rights.

Changes to the Methodology Order

The Methodology Order has been amended several times to address legal findings made by the Water Court[xxxiii] upon judicial review. However, the Fifth Amended Methodology Order, issued in April 2023, made changes based on the Department’s further data acquisition and additional analyses. The changes were made because “the Director should use available data, and consider new analytical methods or modeling concepts, to evaluate the methodology.”[xxxiv]

Specifically, the Fifth Amended Methodology Order contains two significant changes. First, while the Fourth Amended Methodology Order used an average of the years 2006, 2008, and 2012 for the BLY, the Department determined that data obtained from 2014-2021 indicated that particular average of years no longer satisfied the criteria for a BLY.[xxxv] The Director found that the criteria for a BLY were satisfied by 2018 and 2020.[xxxvi] The Director then selected 2018 as the new BLY, concluding that using 2018 for the BLY “protects the senior while excluding extreme years from consideration.”[xxxvii]

Second, the ESPAM analysis was changed from steady-state to transient simulation. Steady-state is a condition of a system that does not change in time,[xxxviii] whereas transient simulation attempts to predict changes over time. Early versions of ESPAM used a steady-state analysis to calculate impacts of water use on the ESPA. When using a steady-state analysis, ESPAM “can only model increases in aquifer discharge to the Snake River resulting from continuous curtailments of an identical magnitude and location until the impacts of curtailment are fully realized.”[xxxix] This calculation does not account for the time to reach steady state or when the impacts would be realized. The current ESPAM can perform a transient simulation which “predict[s] the timing of changes in river reach gains.”[xl]

To illustrate the difference between steady-state and transient model simulation, the Director ran ESPAM simulations using both steady-state and transient for 2023. The Director found that curtailment using the steady-state analysis will only offset 9-15% of the predicted shortfall, while a transient analysis will offset the full predicted shortfall.[xli] This means that using transient analysis stands to provide the senior water users more water at the time and place needed. But it also means that the Department would have to curtail more junior groundwater rights to meet the needs of the Coalition in a particular year.

The Director of the Department held a hearing on the Fifth Amended Methodology Order in June 2023. On July 19, 2023, the Director issued two orders. The first, Post-Hearing Order Regarding Fifth Amended Methodology Order, addresses the issues discussed at the hearing.[xlii] The second, a Sixth Final Order Regarding Methodology for Determining Material Injury to Reasonable In-Season Demand and Reasonable Carryover (“Sixth Amended Methodology Order”),[xliii] “correct[s] data in the Fifth Methodology Order found to be in error during the June 6 Hearing” and edits “other non-substantive matters in the Fifth Methodology Order.”[xliv] The Sixth Amended Methodology Order did not change the selection of BLY or the use of transient model simulations. It is expected that a petition for judicial review of the orders will be filed. Although the Sixth Amended Methodology Order is not yet set in stone, it nevertheless has implications for all water users in the Eastern Snake Plain, surface, and groundwater users alike.

Why it Matters

In April 2023, based on the Fifth Amended Methodology Order, the Director determined that “ground water rights-bearing priority dates later than December 30, 1953, must be curtailed to produce the volume of water equal to the predicted” shortfall.[xlv] This is much earlier than curtailment dates determined in April in prior years. For example, the curtailment date for 2022 was December 25, 1979,[xlvi] in 2019 it was August 25, 1991,[xlvii] and in 2016 it was February 8, 1989.[xlviii] While the mid-season evaluation of actual need showed there was no shortfall,[xlix] the changes present in the Fifth and Sixth Amended Methodology Orders are still relevant as they will continue to apply in the future.

Ordering curtailment or mitigation for a larger pool of groundwater users can be costly. The April 2023 predicted shortfall was 75,200 acre-feet of water.[l] To put that in perspective, one acre-foot of water is 325,851 gallons and one dairy cow is estimated to need 35 gallons of water per day.[li] The cost for water right rentals is $23 per acre-foot, which equates to almost $1.73 million.[lii] In years where there is a water shortfall, the option to rent may not be available. The uncertainty of water rights rentals has resulted in groundwater users implementing multiple mitigation strategies, such as compensating for their use with groundwater recharge or reducing the amount of water used.[liii] Groundwater recharge requires infrastructure and groundwater users must spend money not only to build the infrastructure but to identify a suitable site and obtain water rights. Reduction of water use means less crops grown, and less money earned, which affects livelihoods and the Idaho economy. This is an issue that affects so many in Idaho, so keep your eyes open for further headlines.

Meghan M. Carter is a deputy attorney general representing the Idaho Department of Water Resources. She’s been in her position for 10 years and is amazed at what she still doesn’t know about Idaho water law. The views expressed in this article do not reflect those of the Office of the Attorney General or IDWR.

[i] Possible Water Curtailments Even in a Good Year, AG Proud (May 1, 2023), https://www.agproud.com/articles/57506-possible-water-curtailments-even-in-a-good-year.

[ii] Clark Corbin, New Idaho Department of Water Resources Order Would Force 900 Groundwater Users to Curtail Use, Idaho Capital Sun (Apr. 28, 2023), https://idahocapitalsun.com/2023/04/28/new-idaho-department-of-water-resources-order-would-force-900-groundwater-users-to-curtail-use/.

[iii] Fifth Amended Final Order Regarding Methodology for Determining Material Injury to Reasonable In-Season Demand and Reasonable Carryover, In the Matter of Distribution of Water to Various Water Rights Held by or for the Benefit of A & B Irrigation District, American Falls Reservoir District #2, Burley Irrigation District, Milner Irrigation District, Minidoka Irrigation District, North Side Canal Company, and Twin Falls Canal Company, No. CM-DC-2010-001 (Idaho Dept. of Water Resources, filed Apr. 21, 2023), available at https://idwr.idaho.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/legal/CM-DC-2010-001/CM-DC-2010-001-20230421-Fifth-Amended-Final-Order-Regarding-Methodology.pdf.

[iv] Wesley Hipke, Paul Thomas, and Noah Stewart-Maddox, Idaho’s Eastern Snake Plain Aquifer Managed Aquifer Recharge Program, 60 Groundwater 648, 648 (2022).

[v] Id. at 648–49.

[vi] Id. at 649.

[vii] Interview with Jennifer Sukow, Engineer, Idaho Dept. of Water Resources (July 5, 2023).

[viii] Water Supply Snow Water Equivalency, Idaho Department of Water Resources (Mar. 16, 2021), https://idwr.idaho.gov/water-data/water-supply/snow-water-equivalency/.

[ix] I.C. § 42-106 (“As between appropriators, the first in time is first in right.”)

[x] IDAPA 37.03.11.010.04.

[xi] IDAPA 37.03.11.010.03.

[xii] Enhanced Snake Plain Aquifer Model Version 2.1 Final Report, 4 (Jan. 18, 2013), available at https://research.idwr.idaho.gov/files/projects/espam/browse/ESPAM_2_Final_Report/ESPAM21FinalReport.pdf.

[xiii] Jennifer Sukow, Model Calibration Report Eastern Snake Plain Aquifer Model Version 2.2, Idaho Department of Water Resources (May 2021), https://research.idwr.idaho.gov/files/projects/espam/browse/ESPAM22_Reports/ModelCalibrationRpt/ModelCalibration22_Final.pdf.

[xiv] Petition for Water Right Administration and Designation of the Eastern Snake Plain Aquifer as a Ground Water Management Area, In the Matter of the Petition for Administration by A & B Irrigation District, American Falls Reservoir District #2, Burley Irrigation District, Milner Irrigation District, Minidoka Irrigation District, North Side Canal Company, and Twin Falls Canal Company (Idaho Dept. of Water Resources, filed Jan. 14, 2005), available at https://idwr.idaho.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/legal/swc-delivery-call/SWC-20050114-SWC-Call-Secondary-Filing.pdf.

[xv] Id. at ¶ 16

[xvi] Id.

[xvii]Order, In the Mater of Distribution of Water to Various Water Rights Held by or for the Benefit of A&B Irrigation District, et al. (Idaho Dept. of Water Resources, filed Feb. 14, 2005), available at https://idwr.idaho.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/legal/swc-delivery-call/SWC-20050214-First-Order-in-Response-to-Surface-Coalition.pdf.

[xviii]Seventh Supplemental Order Amending Replacement Water Requirements, In the Matter of Distribution of Water to Various Water Rights Held by or for the Benefit of A & B Irrigation District, et al. (Idaho Dept. of Water Resources, filed Dec. 20, 2007), available at https://idwr.idaho.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/legal/swc-delivery-call/SWC-20071220-Seventh-Supplemental-Order-Amending-Replacement-Water-Requirements.pdf.

[xix] The three-year delay between the initial conflict and the hearing on the conflict stemmed from requests for schedule changes and a case challenging the Conjunctive Management Rules, the administrative rules governing a delivery call between surface and ground water users.

[xx] Opinion Constituting Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law and Recommendation, 29, In the Matter of Distribution of Water to Various Water Rights Held by or for the Benefit of A & B Irrigation District, et al. (Idaho Dept. of Water Resources, filed Apr. 29, 2008), available at https://idwr.idaho.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/legal/swc-delivery-call/SWC-20080429-SWC-Rec-Order.pdf.

[xxi] Final Order Regarding the Surface Water Coalition Delivery Call, 4, In the Matter of Distribution of Water to Various Water Rights Held by or for the Benefit of A & B Irrigation District, et al. (Idaho Dept. of Water Resources, filed Sept. 5, 2008), available at https://idwr.idaho.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/legal/swc-delivery-call/SWC-20080905-SWC-Final-Order.pdf.

[xxii] Id. at 5.

[xxiii] Id. at 6.

[xxiv] Second Amended Final Order Regarding Methodology for Determining Material Injury to Reasonable In-Season Demand and Reasonable Carryover, 2, In the Matter of Distribution of Water to Various Water Rights Held by or for the Benefit of A & B Irrigation District, et al., No. CM-DC-2010-001 (Idaho Dept. of Water Resources, filed June 23, 2010), available at https://idwr.idaho.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/legal/CM-DC-2010-001/CM-DC-2010-001-20100623-Amended-Final-Order.pdf.

[xxv] IDAPA 37.03.11.010.14.

[xxvi] IDAPA 37.03.11.042.

[xxvii] Id. at 12

[xxviii] Final Order Regarding the Surface Water Coalition Delivery Call, supra note 21, at 5.

[xxix] Second Amended Final Order Regarding Methodology for Determining Material Injury to Reasonable In-Season Demand and Reasonable Carryover, supra note 24,at 22.

[xxx] Id. at 34–36.

[xxxi] Id. at 36.

[xxxii] Id. at 37–38.

[xxxiii] Per Idaho Supreme Court Administrative Order, all petitions for judicial review regarding the administration of water rights from the Department are assigned to the Adjudication Court of the Fifth Judicial District. Administrative Order, In the Matter of the Appointment of the SRBA District Court to Hear All Petitions for Judicial Review from the Department of Water Resources Involving Administration of Water Rights, (Dec. 9, 2009), available at http://srba.state.id.us/Images/sct%20order.pdf.

[xxxiv] Fifth Amended Final Order Regarding Methodology for Determining Material Injury to Reasonable In-Season Demand and Reasonable Carryover, supra note 3, at 1.

[xxxv] Id. at 11.

[xxxvi] Id. at 12.

[xxxvii] Id.

[xxxviii] Id. at 30.

[xxxix] Id.

[xl] Id.

[xli] Id.

[xlii] Post-Hearing Order Regarding Fifth Amended Methodology Order, In the Matter of Distribution of Water to Various Water Rights Held by or for the Benefit of A & B Irrigation District, et al. (Idaho Dept. of Water Resources, filed (July 19, 2023), available at https://idwr.idaho.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/legal/CM-DC-2010-001/CM-DC-2010-001-20230719-Post-Hearing-Order-Regarding-Fifth-Amended-Methodology-Order.pdf.

[xliii] Sixth Final Order Regarding Methodology for Determining Material Injury to Reasonable In-season Demand and Reasonable Carryover, In the Matter of Distribution of Water to Various Water Rights Held by or for the Benefit of A & B Irrigation District, et al. (Idaho Dept. of Water Resources, filed July 19, 2023), available at https://idwr.idaho.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/legal/CM-DC-2010-001/CM-DC-2010-001-20230719-Sixth-Final-Order-Regarding-Methodology.pdf.

[xliv] Id. at 2.

[xlv] Final Order Regarding April 2023 Forecast Supply (Methodology Steps 1-3), 4, In the Matter of Distribution of Water to Various Water Rights Held by or for the Benefit of A & B Irrigation District, et al. (Idaho Dept. of Water Resources, filed Apr. 21, 2023), available at https://idwr.idaho.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/legal/CM-DC-2010-001/CM-DC-2010-001-20230421-Final-Order-Regarding-April-2023-Forecast-Supply-Methodology-Steps-1-3.pdf.

[xlvi] Final Order Regarding April 2022 Forecast Supply (Methodology Steps 1–3), 5, In the Matter of Distribution of Water to Various Water Rights Held by or for the Benefit of A & B Irrigation District, et al. (Idaho Dept. of Water Resources, filed Apr. 20, 2022), available at https://idwr.idaho.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/legal/CM-DC-2010-001/CM-DC-2010-001-20220420-Final-Order-Re-April-2022-Forecast-Supply-Methodology-Steps-1-3.pdf.

[xlvii] Final Order Regarding April 2019 Forecast Supply (Methodology Steps 1–3), 6, In the Matter of Distribution of Water to Various Water Rights Held by or for the Benefit of A & B Irrigation District, et al. (Idaho Dept. of Water Resources, filed Apr. 11, 2019), available at https://idwr.idaho.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/legal/CM-DC-2010-001/CM-DC-2010-001-20190411-Final-Order-Regarding-April-2019-Forecast-Supply-Steps-1-3.pdf.

[xlviii] Final Order Regarding April 2016 Forecast Supply (Methodology Steps 1 -3), 6, In the Matter of Distribution of Water to Various Water Rights Held by or for the Benefit of A & B Irrigation District, et al. (Idaho Dept. of Water Resources, filed Apr. 19, 2016), available at https://idwr.idaho.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/legal/CM-DC-2010-001/CM-DC-2010-001-20160419-Final-Order-Regarding-April-2016-Forecast-Supply-Meth-Steps-1-3.pdf.

[xlix] Order Revising April 2023 Forecast Supply and Amending Curtailment Order (Methodology Steps 5 & 6), In the Matter of Distribution of Water to Various Water Rights Held by or for the Benefit of A & B Irrigation District, et al. (Idaho Dept. of Water Resources, filed July 19, 2023), available at https://idwr.idaho.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/legal/CM-DC-2010-001/CM-DC-2010-001-20230719-Order-Revising-April-2023-Forecast-Supply-and-Amending-Curtailment-Order-Methodology-Steps-5-6.pdf.

[l] Final Order Regarding April 2023 Forecast Supply (Methodology Steps 1-3), supra note 45, at 6.

[li] Water Use Information, https://idwr.idaho.gov/water-rights/water-use-information/.

[lii] Water Supply Bank Pricing, https://idwr.idaho.gov/iwrb/programs/water-supply-bank/pricing/.

[liii] IGWA’s Amended Notice of Mitigation, In the Matter of Distribution of Water to Various Water Rights Held by or for the Benefit of A & B Irrigation District, et al. (Idaho Ground Water Appropriators, Inc., filed June 1, 2023), available at https://idwr.idaho.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/legal/CM-DC-2010-001/CM-DC-2010-001-20230601-IGWAs-Amended-Notice-of-Mitigation.pdf.

Keeping “Current” with the Idaho Water Adjudications

By Lacy Rammell-O’Brien

Greek philosopher Heraclitus of Ephesus is attributed with the expression, “No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man.”[i] The Idaho Water Adjudications are much like Heraclitus’ river, flowing and changing as they roll through the state. Long-time followers of the Idaho Water Adjudications know that on November 19, 1987, the Snake River Basin Adjudication commenced and opened decades of litigation.[ii] Since that time, four more general stream adjudications have commenced. This article summarizes the changes since October 2020, when the last Water Adjudications update was published in The Advocate.[iii]

An adjudication is a court proceeding resulting in the judicial determination of water rights claimed by parties asserting validity and ownership of those rights.[iv] The Idaho Water Court, based out of the Fifth Judicial District in Twin Falls, presides over the Idaho Water Adjudications.[v] Pursuant to statute, the Idaho Department of Water Resources (“IDWR”) is not a party to the Adjudications.[vi] IDWR’s role is as an “independent expert and technical assistant to assure that claims to water rights acquired under state law are accurately reported” and to “make recommendations as to the extent of beneficial use and administration of each water right under state law.”[vii]

Snake River Basin Adjudication (“SRBA”)

The SRBA remains one of the largest legal adjudications in U.S. history, issuing over 158,000 decrees.[viii] The SRBA covered administrative basins in 38 of Idaho’s 44 counties. [ix] On August 26, 2014, the Water Court issued the Final Unified Decree. The Final Unified Decree is “conclusive as to the nature and extent of all water rights within the Snake River Basin within the State of Idaho with a priority date prior to November 19, 1987[…].”[x] The Court explicitly retained jurisdiction over “[a]ny domestic and stock water right, as defined in Idaho Code § 42-111 (1990), Idaho Code § 42-1401A(5) (1990), and Idaho Code § 42-1401A(12) (1990), the adjudication of which was deferred in accordance with this Court’s June 28, 2012, Order Governing Procedures in the SRBA for Adjudication of Deferred De Minimis Domestic and Stock Water Claims”.[xi] The Water Court has continued to decree “deferred” domestic and stock water claims in accordance with the Final Unified Decree.

On November 15, 2021, the United States filed a Motion to Adjudicate Deferred De Minimis Domestic and Stock Water Claims, asking the Court to set a deadline for the filing of all deferred de minimus domestic and stock water right claims in the SRBA.[xii] The United States argued that it had waived its sovereign immunity under the McCarran Amendment with the understanding that the “adjudication of rights to the use of water of a river system or other source” would be conclusive as to all water rights within the SRBA.[xiii] The McCarran Amendment allows for a limited waiver of the United States’ sovereign immunity so that it may appear as a party in state court general stream adjudications.[xiv] The United States argued that the continued taking of deferred claims was in violation of the McCarran Amendment and the Deferral Stipulation executed and filed by the State of Idaho and the United States on December 20, 1988.[xv] The Water Court held a status and scheduling conference on February 15, 2022, during which it appointed Special Master Theodore Booth as settlement moderator and stayed litigation.[xvi] Following months of negotiations, the parties agreed to a further stay of proceedings until December 31, 2023.[xvii]

Coeur d’Alene – Spokane River Basin Adjudication (“CSRBA”)

The CSRBA is Phase One of the North Idaho Adjudication (“NIA”).[xviii] On July 8, 2008, the State of Idaho filed a Petition to Commence the CSRBA.[xix] On November 12, 2008, Judge John Melanson issued the Commencement Order.[xx] The CSRBA contains five administrative basins (91-95) covering Benewah, Bonner, Clearwater, Kootenai, Latah, and Shoshone counties.[xxi]

State-based claims in the CSRBA are mostly resolved. As of July 5, 2023, there are eight unresolved state-based claims in Basin 95 Part 1 and six unresolved state-based claims in Basin 95 Part 2.

As of July 5, 2023, there are 284 unresolved federal reserved claims across basins 91-95. The United States filed claims to federal reserved water rights as trustee on behalf of the Coeur d’Alene Tribe of the Coeur d’Alene Indian Reservation. The United States cited “Winters v. United States, 207 U.S. 564 (1908) and its progeny, as well as the operative documents and circumstances surrounding the creation of the Coeur d’Alene Reservation” as the basis for its claims. [xxii] The Water Court bifurcated proceedings on the Coeur d’Alene Tribe’s claims.[xxiii] The Water Court first evaluated “entitlement” to particular uses of water, to be followed by the “quantification” stage of the amount of water associated with those uses.[xxiv]

On September 5, 2019, the Idaho Supreme Court issued its decision on the “entitlement” phase of the proceedings, holding that the Coeur d’Alene Tribe had reserved water rights consisting of domestic uses, agricultural uses, hunting and fishing uses, plant gathering, and cultural uses.[xxv] The Idaho Supreme Court also affirmed the holding of the Water Court that the Coeur d’Alene Tribe’s water rights included instream flows on the Reservation and that the Tribe voluntarily relinquished rights to off-Reservation instream flows.[xxvi]

Following the decision of the Idaho Supreme Court, the parties agreed to a stay of litigation.[xxvii] They pursued settlement negotiations with a court-appointed mediator.[xxviii] At a status conference held on April 18, 2023, the parties informed the Water Court that mediation had been unsuccessful.[xxix] On May 26, 2023, the Water Court entered an Order lifting the litigation stay, along with a scheduling order setting trial for April 2026.[xxx]

Palouse River Basin Adjudication (“PRBA”)

The PRBA is Phase Two of the NIA.[xxxi] On October 3, 2016, the State of Idaho filed a Petition to Commence the PRBA.[xxxii] On March 1, 2017, Judge Eric Wildman issued the Commencement Order.[xxxiii] The PRBA covers one administrative basin (87) in Benewah, Latah, and Nez Perce counties.[xxxiv] As of July 5, 2023, there are 182 objections to 101 contested subcases in the PRBA, with 2,212 water right claims pending decree.

The rolling hills of the Palouse have set the stage for a shared issue with several players. Among the many individuals and entities that filed claims in the PRBA are the State of Idaho, the City of Moscow, the Potlatch entities, Schweitzer, the University of Idaho, the Nez Perce Tribe, and the United States as Trustee on behalf of the Nez Perce Tribe and Allottees of the Nez Perce Indian Reservation.[xxxv]

At the heart of the United States’ and the Nez Perce Tribe’s objections to state-based claims and the federal reserved claims are two treaties. The first is the Treaty of 1855.[xxxvi] The second is the Treaty of 1863, which states in relevant part: “The United States also agree to reserve all springs or fountains not adjacent to, or directly connected with, the streams or rivers within the lands hereby relinquished, and to keep back from settlement or entry so much of the surrounding land as may be necessary to prevent the said springs or fountains from being enclosed; and further, to preserve the perpetual right of way to and from the same, as watering places, for the use in common of both whites and Indians.”[xxxvii]

The United States argues that a portion of the PRBA includes lands that were ceded by the Nez Perce Tribe as part of the Treaty of 1863. The United States objected to certain state-based claims on the grounds that they should recognize corresponding federal claims for “up to half of the natural spring flow” based on the phrase “for the use in common” in the Treaty.

The Nez Perce Tribe filed joinder in the objection of the United States, arguing that “up to half of natural spring flow” should be recognized in the claims as “expressly reserved for the use of the Tribe and its members.”[xxxviii] The federal reserved claims filed by the United States and Nez Perce Tribe closely mirror the state-based surface water claims. Like the federal reserved claims in the CSRBA, the PRBA federal/tribal claims rely on the Winters doctrine and related caselaw.

The parties are now subject to a protective order issued by the Water Court.[xxxix] They are currently in negotiations with an eye toward settlement of the United States and Nez Perce Tribe’s objections and federal reserved claims in the basin. [xl]

Clark Fork – Pend Oreille River Basins Adjudication (“CFPRBA”)

The CFPRBA is Phase Three of the NIA.[xli] On October 23, 2020, the State of Idaho filed a Petition to commence a general adjudication of all rights arising under state or federal law to the use of surface and ground waters from the Clark Fork – Pend Oreille River basins water system and for the administration of such rights.[xlii] On June 15, 2021, Judge Wildman entered the Commencement Order for the CFPRBA pursuant to Idaho Code § 42-1406B.[xliii]

The CFPRBA covers two administrative basins (96 and 97) in Bonner, Boundary, and Kootenai counties.[xliv] It does not include administrative basin 98.[xlv] Claims filing ended in the CFPRBA on June 23, 2023, although second-round service and motions to file late claims may yield more filings. As of June 8, 2023, there have been 7,543 state-based claims and 24 federal reserved claims filed in the CFPRBA.

IDWR anticipates up to 9,000 claims to be filed in the CFPRBA and hopes to have Part 1 of the Basin 97 Director’s Report completed and filed with the Idaho Water Court in 2024.

Bear River Basin Adjudication (“BRBA”)[xlvi]

On November 20, 2020, the State of Idaho filed a Petition seeking commencement of a general adjudication of all rights arising under state or federal law to the use of surface and ground waters from the Bear River basin water system and for the administration of such rights.[xlvii] On June 15, 2021, Judge Wildman entered the Commencement Order for the BRBA pursuant to Idaho Code § 42-1406C.[xlviii]

The BRBA covers four administrative basins (11, 13, 15, and 17) in Bannock, Caribou, Cassia, Franklin, Oneida, and Power counties.[xlix] As of June 8, 2023, 816 state-based claims have been filed in the BRBA. IDWR anticipates that approximately 13,000 claims will be filed in the BRBA.

As of July 5, 2023, property owners in Basin 11 have received Commencement Notices alerting them to the need to file their water right claims with IDWR. In addition to the new field office in Preston, Idaho, staff from IDWR’s adjudication section have held a week-long public claim-taking workshop in Montpelier, Idaho to help people in Basin 11 file their claims. IDWR is proceeding with the goal of filing the Basins 11 and 13 Director’s Report with the Idaho Water Court in 2026.

Conclusion

Heraclitus is remembered for his philosophy of constant change. The Idaho Water Adjudications, water users, and law practitioners are not the same as they were in 1987. The evolution of the Adjudications, like the waters of Idaho and those who use them, will guide this winding river toward resolution. The Idaho Water Adjudications flow onward, collecting claims and issuing decrees that clarify and record how water is being used statewide.

Lacey Rammell-O’Brien is a deputy attorney general representing the Idaho Department of Water Resources. She is a fifth-generation Idahoan and third-generation admirer of Gary Larson’s The Far Side. The views expressed in this article do not reflect those of the Office of the Attorney General of IDWR.

[i] Daniel W. Graham, “Heraclitus”, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2021 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.),https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/heraclitus/.

[ii] Commencement Order, In re SRBA Case No. 39576 (Nov. 19, 1987).

[iii] Meghan M. Carter & Jennifer R. Wendel, Water Rights Adjudications in Idaho Have Statewide Impacts, 63 ADVOCATE 16 (2020).

[iv] A “general adjudication” is defined in Idaho Code section 42-1401A(5) as “an action both for the judicial determination of the extent and priority of the rights of all persons to use water from any water system within the state of Idaho that is conclusive as to the nature of all rights to the use of water in the adjudicated water system, except as provided in section 42-1420, Idaho Code, and for the administration of those rights.”

[vi] Idaho Code § 42-1401B.

[vii] Id.

[viii] Ann Y. Vonde et al., Understanding the Snake River Basin Adjudication, 52 IDAHO L. REV. 53 (2016).