Wellness, Schmellness: What is it All About?

By Susan P. Mauk and Jamie Shropshire

Recently, state bars and the American Bar Association have promoted wellness initiatives for their members, championing the value of meditation, yoga, and walks in the park. But why?

As two members of the Idaho Lawyer Assistance Program Committee, we have seen the tragedy of substance abuse and mental health issues that paralyze many of our colleagues and the positive impact of focusing not only on intervention but promoting sustainable wellness. This article describes what this is and how anyone can benefit from practicing the techniques associated with it.

Why Wellness

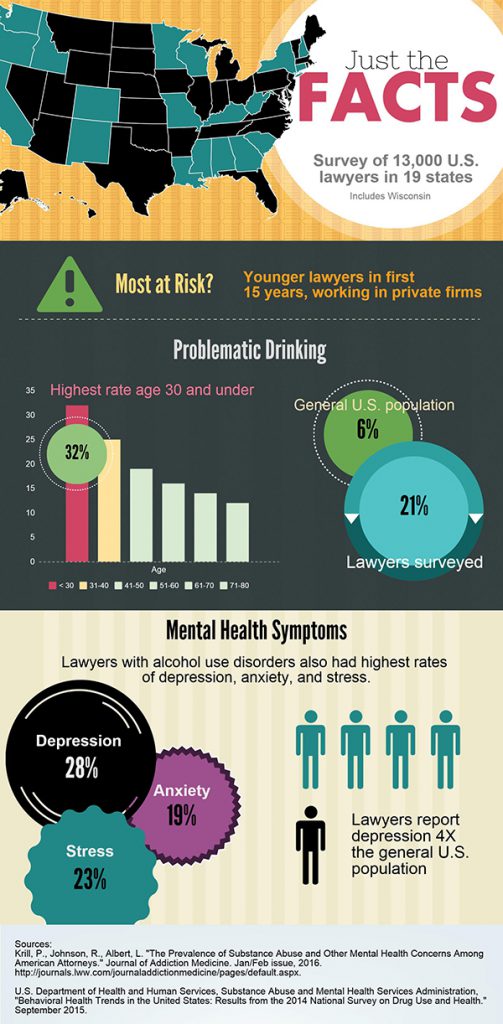

Recently, the results of two self-reporting surveys of lawyers, judges, and law students were released. The first was conducted by the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation in 2016 of 12,825 lawyers and judges; the second surveyed 11,300 law students from 15 law schools from various regions of the country – approximately 3,400 students responded.

What both surveys found is that we suffer from a much higher rate of alcoholism, drug abuse, and mental health issues than the general population.

Based on their responses, law students need to be considered both for intervention and for sustainable wellness. Approximately 17% of students were diagnosed with depression and over 35% were diagnosed with mild to severe anxiety. Additionally, 21% of law students admitted to problem drinking. Law students in their first year have the same incidence of alcohol problems as the general population of a similar age, approximately 10%. At the end of their second year, the survey responses indicate that the rate increases to 21%. [ii]

We have the highest rate of alcoholism of any profession. Surgeons, who would seem to be in a profession that should have a comparable rate of alcohol problems have a rate of just 15%. What explains the difference. Certainly, the adversarial nature of our jobs is a significant factor. Surgeons don’t have another surgeon on the other side of the operating table arguing how badly the operation is going and how the surgeon’s technique and procedures are all wrong.[iii]

We also, tragically, have a high rate of suicide. Nationally, that rate is 14 per 100,000. [iv] The Idaho State Bar of about 6700 members has been impacted by five suicides of colleagues in the last two years.

What all this information tells us is that, at every level of our profession, we don’t ask for help.

We don’t ask for help primarily, as both surveys tell us because we fear that others will find out and we fear the loss of our license to practice law or the loss of our ability to get a license to practice. [v] Only 7% of attorneys seek help for alcohol or drug use and only 22% of those used programs that were designed for legal professionals, even though it appears, from the information available, that programs specifically designed for lawyers have a better rate of success. [vi]

Yet, almost every state has a committee or organization that assists attorneys with substance abuse, other addictions, and mental health problems. Those organizations and committees serve members of the legal profession, their families, and law students free of charge, anonymously, and confidentially. They are neither related to nor do they report to Bar disciplinary counsel.

So, the answer to the question, “Why wellness?” seems to be obvious. At best we ignore our problems, or we simply accept the fear and anxiety and their consequences. At worst, we embrace them by continuing with practices and procedures that promote their tragic results.

In the years since the Hazelden report, [vii] mechanisms such as interventions and programs for recovery specifically designed to address the legal community abound; yet what is increasingly clear is that these approaches are not sustainable without wellness as a foundation.

What is Wellness?

What is wellness and why has it received so much attention in recent years? Wellness is a process, a way of orienting oneself towards life, examining actions and responses as they impact one’s body, mind and, in some cases spirit. Wellness is about feeling good emotionally and physically and using such tools as diet and exercise to get there.

Wellness is not only the absence of disease. It is about how one listens, identifies needs, takes care of oneself, and connects to the world one lives in. It is about making small, incremental changes in how you eat, sleep, communicate with others, or handle stress – in general, how you navigate your life.

There is no “right” way to be well. We live in a world with high-pressure work environments, toxic exposures, social and familial stress, and medication overuse (to name but a few of the challenges of modern life). Many wellness authorities have identified several areas of practice to look at wellness in a holistic, multifaceted way.

- Meditation: a state of quiet contemplation that involves turning your focus inward for a few minutes at a time to access a deeper reality.

- Visualization: re-patterning your energy, feeding your brain new images to replace the old ones, retraining your thinking.

- Pleasurable Activities: engaging in activities that bring enjoyment to your life.

- Conscious Eating: paying attention to what you eat to be consuming healthy and nutritious foods.

- Exercise: finding a routine in which you can do 30 to 45 minutes a day, three to five times a week which leaves you feeling more invigorated and alert; could include cardiovascular activities, strength training, yoga, tai chi, etc.

- Self-Work: to look at where we are in life, to set some goals for where we would like to be and to chart a course as to how to get there.

- Spiritual Practice: bringing us to identifying with something larger than ourselves.

- Service: delving into some form of giving back, and to feel useful and grateful to have something to give.

By exploring our behavior in any one of these areas, we can begin to know our bodies, to understand our minds, and, for some, to explore a spiritual path.

Why the surge in curiosity about sustainable wellness in the past 10 to 15 years? As the life expectancy in the United States has increased, people want to know how to live out these additional years in greater health; and while the world has never witnessed a time of greater promise for improving human health, we don’t want to rely on technology alone to ensure a better future. Cultivating wellness skills can help attorneys lead healthier lifestyles in ways of their own choosing. Medical advances are only one part of the picture; cultivating wellness can contribute enormously to our mental, physical, and emotional wellbeing.[viii]

Some research suggests that before they enter law school, some law students are healthier, both physically and mentally, then the general population. They generally start school with a strong sense of their own values and a sense of themselves. Law school, it is observed, encourages students to take the emotion out of their decisions; “once you start reinforcing that with grades and money, you aren’t just suppressing your emotions, you are fundamentally changing who you are.”[ix]

If the data on law students is discouraging, these findings are compounded when we look at young lawyers especially during the first 10 years of practice. They, too, are caught up by the demands of deadlines, the unreasonable expectations of clients, billing pressures, long hours, and the pressure to perform. Many are still grappling with law school debt, beginning to raise young families, and find themselves with an increase in depression, pessimism, and a kind of isolation they didn’t expect. “Lawyers are a help-rejecting profession,” one author comments, mistakenly believing that if they are vulnerable, they are weak. [x]

The Hazelden study and others which followed identified lawyers’ perfectionism and pessimism as qualities contributing to their vulnerability to depression and stress. They don’t like to appear needy or dependent and will tend to sacrifice healthy habits such as eating healthfully or getting enough sleep to meet unrealistic expectations.

Their perfectionism leads to an overdeveloped sense of control so that if things don’t go as planned, they blame themselves. As “paid worriers” they tend to see problems everywhere, even if they do not exist. As pessimists, they tend to see negative events as persistent, pervasive, and permanent.

As Will Meyerhofer, an attorney turned clinical social worker comments, “The official number is that something like a gazillion lawyers are stressed out and that amounts to a bajillion percent of the profession.” Is it any wonder that there is a greater incidence of both suicidal ideation and actual suicides among the legal profession than among non-lawyers?[xi]

Where does wellness come into play? The good news is that with greater awareness of these patterns has come widespread support for wellness programs both at law schools and bar associations around the country. There are meditation classes specifically designed for lawyers, online meditation programs, podcasts, and blogs, as well as instructional DVDs.

There are mindfulness training programs which provide comprehensive approaches to relieve stress, enhance daily living, along with toolboxes which contain simple exercises one can do on a daily basis which produce powerful results. Techniques of mindfulness that focus on paying attention to the present moment improve one’s ability to make decisions; “a mindfulness practice makes us better…ethical decision-makers. And that translates into better lawyering.”

Eating more healthily may mean learning the value of a lean, green, and clean diet as well as how to put together a low carbohydrate, moderate protein, and high-fat combination; making such changes as finishing your last meal two to three hours before you go to bed, and making mealtime enjoyable, not something you race through while sitting at your desk.

For many, doing multiple things at once may seem like a normal, even practical way to manage a busy life, but juggling several tasks at once takes a toll on our wellbeing. Actions which move you away from multitasking to focus on one thing at a time, such as doing progressive muscle relaxation exercises which could take minutes, learning deep breathing exercises which can be helpful even if we do them for brief periods of time, journaling on a regular basis, or finding a physical exercise routine which helps to release endorphins, help to cultivate “learned optimism,” a predisposition to see things from a more positive perspective. All of these behavioral changes can lead to greater engagement and satisfaction with life.

Lawyers sometimes wear their stress as a badge of honor as though to be on edge much of the time means one is successful. We do know that those who experience a lot of anxiety, who are frequently overwhelmed, don’t sleep well and are often fatigued may be candidates for long-term depression. Seeking help before you really need it, whether by embracing any of these techniques or obtaining the assistance of a licensed behavioral health professional can step in the right direction.

A Signa study years ago identified the loneliness and isolation experienced by members of the legal profession as a greater predictor of early death than smoking.[xii] Practicing gratitude, fostering mindfulness, cultivating genuine friendships, developing emotional and cognitive flexibility all contribute to self-care and can put you on a path to wellness.

For the past several years, the Idaho Lawyer Assistance Program has broadened its scope to promote wellness in members of the legal profession. The demands of the profession are not going to change; however, there are ways to make a difference which will have a positive impact on individual practitioners and the profession as a whole.[xiii] Practicing wellness through even the smallest positive change starts a ripple effect which soon impacts others to do the same. Purpose is not discovered; it comes from following your passions and interests and doing the small things that are important to you. And we are all entitled to a purposeful, healthy, and satisfying life.

A Healthy Profession

Having looked at what we can do for ourselves, are there things that we can do as a profession to lessen the impact of anxiety, depression, and substance abuse. Some of the codes and standards that we have adopted, if followed with our collective health in mind, can help.

There are several sections of the Idaho Rules of Professional Conduct that, if rigorously observed, could assist this effort. The Preamble states: “A lawyer should use the law’s procedures only for legitimate purposes and not to harass or intimidate others.”[xiv] Rule 1.3, Commentary, paragraph 1: “The lawyer’s duty to act with reasonable diligence does not require the use of offensive tactics or preclude the treating of all persons involved in the legal process with courtesy and respect.”[xv] Other notable rules that could lower stress in our daily interactions if practiced are Rules 3.3, 3.4 and 3.5.

Are there other procedures and practices that we should examine. Are there methods other than billable hours for evaluating an attorney’s performance for the purposes of promotion and compensation?

Should we be requiring mediation for many issues that could be solved by ADR, rather than continuing with stressful and exhausting courtroom battles?

What about other procedures that have been adopted regarding our behavior toward each and the public?

The Standards of Civility state that: “An attorney’s conduct should be characterized at all times by personal courtesy and professional integrity in the fullest sense of those terms. (emphasis added)[xvi]. What would the immediate and long-lasting effect if we always treated each other with personal courtesy? There are those who are probably thinking that zealous advocacy doesn’t allow that, but is that really a reason not to practice civility or is just an excuse. “Uncivil, abrasive, abusive, hostile or obstructive conduct impedes the fundamental goal of resolving disputes rationally, peacefully and efficiently. Incivility tends to delay, and often deny, justice.” [xvii]

What if we seriously practiced the principals that our Standards of Civility set out instead of succumbing to the turmoil that strong personalities can sometimes create. If we choose to treat each other with respect our actions can have significant, permanent, and healthy effects for us individually and as a profession.

The Idaho Lawyer Assistance Program has volunteer members in every judicial district who are committed to not only helping our colleagues, law students, and their families cope with the challenges of addiction and mental health, but also to promoting a healthier profession. Find our contacts and other information from the Idaho Lawyer Assistance Program on the Idaho State Bar website at www.isb.idaho.gov.

Susan P. Mauk served for three years as deputy Attorney General and then spent three years in private practice before retiring from the legal profession to pursue a career as a therapist. Susan had a therapy practice for 35 years before her retirement last year.

Jamie Shropshire is a retired attorney who worked most of her career as a prosecutor for Valley County, Nez Perce County, and the Cities of McCall and Lewiston. At her retirement, she served the City of Lewiston as City Attorney. Jamie has been on the Idaho Lawyer Assistance Program Steering Committee since 2004 and has chaired the Committee since 2009.

[i] Joe Forward, Landmark Study: U.S. Lawyers Face Higher Rates of Problem Drinking and Mental Health Issues, Wisconsin Lawyer, Vol. 89, No. 2 (Feb. 2016)

[ii] J.M. Organ, D. Jaffe, K.B. Bender, Survey of Law Student Well-Being, Bar Examiner (Dec. 2015)

[iii] The Problem of Surgeons and Drinking, Physician Health Program (June 15, 2015)

[iv] American Association of Suicidology, www.suicidology.org

[v] supra, Krill et. al.; supra, Organ et. al.

[vi] supra, Krill et al.

[vii] Farmer, supra note 1

[viii] “The Path to Lawyer Well-Being: Practical Recommendations for Positive Change,” from the National Task Force on Lawyer Well-Being.

[ix] Barbara L. Jones, ABA aims for healthier, better lawyers, Minnesota Lawyer (July 3, 2019)

[x] Will Meyerhofer, as quoted in: Stressed Out, Leslie A. Gordon, ABA Journal, No. 07470088, Vol. 101, Issue 7 (July 2015)

[xi] Id.

[xii] Signa study cited in the Arizona State Bar webcast: “Are We Ok?” Wellness and Well-Being Series: “We Can’t Go on Like This: Lawyer Depression, Anxiety and Suicide.”

[xiii] Martha Knudson, Well Being is Key to Maximizing your Success as a Lawyer, Utah Law Journal (Sept. Oct. 2019)

[xiv] Idaho Rules of Professional Conduct (IRCP) Preamble (July 1, 2014)

[xv] IRCP Rule 1.3: DILIGENCE (July 1, 2014)

[xvi] Standards for Civility in Professional Conduct, adopted by the United States District Court, District of Idaho, Courts of the State of Idaho and the Idaho State Bar (2001)

[xvii] Id.