What’s the Plan? Housing Issues During Domestic Violence Cases

Jacob B. Workman[i]

Domestic violence (“DV”) training for attorneys is often focused on the violence portion, and with good reason. Violence from a family or household member has a long-lasting and traumatic impact on survivors. However, what sets domestic violence apart from other societal violence is the adjective domestic.

Domestic violence has a significant and unique impact on the household itself, particularly for women and children.[ii] Sixty-three percent of women experiencing homelessness report being victims of domestic violence or sexual assault.[iii] Women who are DV victims are four times more likely to experience housing instability.[iv] This is partly because domestic violence often leads to other contributing factors of homelessness, such as physical injuries, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and frequent absences from work or school.[v]

This article aims to give family law attorneys expanded understanding of housing problems that arise in domestic violence cases and tools for mitigating the impact on victims. Though female pronouns for victims and male for abusers have been used, domestic violence occurs in the reverse situation and the LGBTQ community.

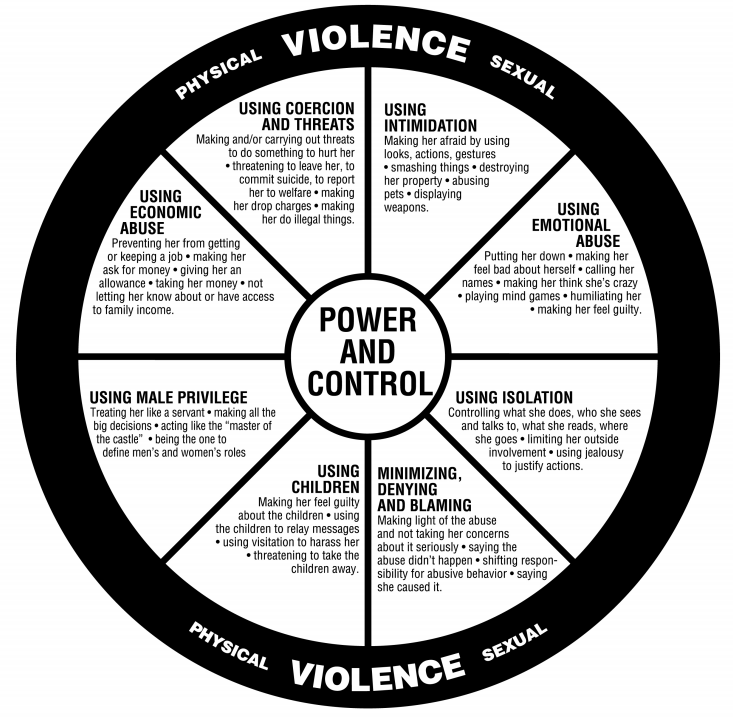

Power and Control

Idaho defines domestic violence as actual or threatened physical injury, sexual abuse, or forced imprisonment of a household member, or of an adult in a dating relationship with the abuser.[vi] The Power and Control Wheel developed by the Domestic Abuse Intervention Project shows the patterns and behavior used by abusers to perpetuate domestic violence.[vii] Housing concerns persist throughout the wheel. Here are some examples:

Using Economic Abuse. Many victims encounter an inability to pay for housing without the financial support of a violent partner. Changes to the rental housing market over the past few years have only exacerbated the problem, with the average cost of rent in Idaho jumping 44% since 2020.[viii] Victims are left with the agonizing decision of enduring the abuse or risking homelessness.[ix]

Coercion, Threats, and Intimidation. Abusers use derogatory, hurtful, and violent words that have special meaning to victims based on the abuser’s behavior in the home. Abusers may intimidate victims about damages they have caused to a rental home during the abuse, claiming it is the victim’s fault and that it could lead to her eviction. With limited housing options, abusers use the victim’s basic needs to establish control over her.

Emotional Abuse and Isolation. The seclusion and privacy of the home can become a tool for abusers to act in ways they never would around other people. Because of this, abusers will often try to isolate victims to the home by demanding to know where victims are at all times and interrogating them when they return. This can lead to victims being cut off from friends, family, and employment, which are vital support systems for victims to be able to end their abuse.

Minimizing, Denying, Blaming, and Male Privilege. Gaslighting is a real struggle for victims to overcome.[x] Abusers may develop a “king of the castle” mentality where because he pays the bills, he makes the rules. This can lead to abusers using those rules to normalize their own abusive behavior as acceptable, appropriate, or even deserved, and can distort victims’ ability to identify or believe in the abuse.

Using Children. Many abusers know how to manipulate a victim based on her concern for her children’s needs, such as housing. Sadly, this sometimes means short-term needs (e.g., where they will sleep tonight) take over long-term needs (e.g., ending an abusive situation) to the benefit of the abuser.

What’s The Plan?

Maybe the most powerful three words you can say to your client are: “What’s the plan?” While clients experiencing domestic violence often have many different problems they would like to solve, your ability as an attorney is to advise on legal solutions to legal matters. Asking “What’s the plan?” allows you to identify shared material goals between you and your client.

What type of living situation does the client want to be in a year from now? What personal or family resources does the client have? What community resources are available? What sort of achievable change would help the client? These types of long-viewed conversations, combined with your legal advocacy and knowledge, can lead to real and lasting stability for your client and any children she has in her care.

Immediate and Long-Term Need

Often, domestic violence cases will come to your office through an ex parte Civil Protection Order (“CPO”) with a pending extension hearing, a No Contact Order issued in a criminal case regarding violence between family members, or a new divorce or custody case. No matter your client’s situation, discussing housing is an immediate priority.

There are a variety of rental and ownership arrangements that can affect your client, including (1) when a CPO is in place, (2) when VAWA may apply, (3) when the victim is not listed on the lease to the dwelling, (4) when there is no formal lease, (5) when the home is solely owned by the abuser, or (6) when there are mounting rent/mortgage/utility payments. It is crucial to understand your client’s current housing situation, what housing changes might be inevitable, a potential timeline, and any changes that might improve your client’s situation in the long-term.

Rental Issues

Regarding a CPO situation, Idaho Code § 32-6306(1)(c) empowers the court to specifically exclude an abuser from a shared dwelling or the home of the victim.[xi] Section 3 of the CPO petition[xii] developed by the Court Assistance Office provides the court with the information needed to make a short-term ruling on housing. Completing this section correctly is crucial to getting immediate help. If you run into issues enforcing a move-out order, domestic violence CPOs are expressly governed by the Idaho Rules of Family Law Procedure.[xiii] I.R.F.L.P. Rule 811 allows you to seek a Writ of Assistance for an order of possession.[xiv]

Many landlords, when approached by a DV victim, are sympathetic to the situation but will desire to stay out of it. If a CPO is issued, providing a copy to the landlord can be appropriate so they know the abuser cannot be on the property. Problems can occur when the victim is not listed on the lease, or it is a month-to-month situation. Some leases in Idaho consider law enforcement involvement at a rental unit to be a lease violation, which may unfairly prejudice domestic violence victims under the Fair Housing Act.[xv]

When a victim is not a signer on a lease, and the lease is month-to-month or verbal, one option is to approach the landlord about creating a new lease with her for the unit. It may require notice to be given to the abuser to terminate the abuser’s lease interest under Idaho Code § 55-307. Such a change would be more difficult if the unit is under a current lease term, but the abuser may agree to rescind the lease if there is a CPO barring him from being there for a substantial amount of time, especially if the agreement would end his financial obligation under the lease.[xvi]

VAWA Protections

The Violence Against Women Act (“VAWA”) contains protections for DV victims in certain rental situations.[xvii] Though VAWA gets “reauthorized” every few years, the reauthorization is for program funding under the Act and the housing protections remain in effect regardless.[xviii] To qualify for the protections, the victim needs to be in a “covered housing program” listed under 34 U.S.C. § 12491(a)(3). Review the lease or research the property where the rental is located to determine if VAWA applies.[xix] VAWA does not apply to private landlord situations, even when the victim has a Section 8 Voucher.[xx]

If VAWA applies, the victim will be protected from (1) being denied housing because she is a DV victim, (2) being evicted or losing federal rental assistance because she is a DV victim, and (3) being evicted for “good cause” or having a lease violation due to DV by the abuser in the unit. Victims do not need to be married to or live with the abuser for VAWA protections to apply. More information on VAWA housing protections is available through Idaho Legal Aid Services’ website. VAWA forms that can be used to assert a victim’s rights are available through the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s website.[xxi]

Abuser as the Homeowner

Sometimes, a cohabitating unmarried couple has a domestic violence situation resulting in the abuser being ordered to leave the home while the victim (and children, if any) remains. On occasion, the abuser who received the move-out order is the sole homeowner. Victims in these situations have no community property laws to rely on and most parties lack a formal contract or written agreement for the living arrangement. Idaho Code § 32-6306(3) specifically states, “[n]o order made under this chapter shall in any manner affect title to real property.” The victim is left in a tough spot where the court is allowed to exclude an abuser from a shared residence but the victim’s legal right to remain is more akin to a tenancy at will under Idaho Code § 55-208[xxii] than an ownership or marital right.

In these situations, the victim will not be able to stay indefinitely and should begin to make plans to move. The abuser could potentially turn to landlord tenant law and provide a 30-day written notice to the victim to vacate.[xxiii] Even if notice is provided or the victim vacates, the address of the CPO’s stay-away order will require court action to modify. The victim should keep a copy of the CPO and evidence she lives in the property (e.g., mail with the resident’s address and her name) close at hand in case it is needed.

Threat of criminal trespass by the abuser is inappropriate given the court’s authority to award temporary possession of a shared dwelling addressed previously. A forcible detainer action by the abuser is also inappropriate given that the victim almost certainly did not begin to reside in the shared dwelling by force, menace, threat of violence, or entering unlawfully while the owner was away.[xxiv] Ultimately, the abuser’s common law claim of ejectment, as opposed to statutory unlawful detainer, may be the most appropriate in these situations because a landlord-tenant relationship was never formally established and rent was never exchanged.[xxv]

For CPO extension hearings, identify these situations and come prepared with a proposed plan if it comes up (e.g., the victim needs 30 days to find a new place after the abuser attacked her).

Payments and Temporary Orders

When an abuser is removed from a home, much of the home’s income may go with him. CPOs do not typically include provisions for an abuser to pay rent or the mortgage on a home that he was just removed from. Victims will need to move toward becoming self-sufficient no matter what their housing plans are.

If there is a divorce or custody case, temporary orders under I.R.F.L.P. Rule 504 can be a solution. Make sure to include not just the rent or mortgage in your request but also utilities and who should pay them. Temporary child support may be the easiest way to keep the children housed. If there is any community interest in the property then it may be appropriate to request both parties help pay the mortgage no matter who is living there temporarily, subject to reallocation upon final judgment.

The more a DV victim can do to become independent, or at least less dependent on the abuser, the better. Community resources can be utilized. If you do not know where to start, have your client call 2-1-1 or visit https://211.idaho.gov/. Additionally, victims may qualify for emergency rental assistance through the Idaho Housing and Finance Association at https://www.idahohousing.com/. Your client may want to apply for a Section 8 Voucher as part of a long-term plan, though the wait list can be around two years. Your local Community Action Partnership or domestic violence center may have other resources. A list of subsidized housing options is found above.[xxvi]

Specific Issues Regarding Kids

Getting your client time to stabilize after leaving a domestic violence situation can affect the court’s considerations regarding the best interest of the children under Idaho Code § 32-717. Housing concerns are present in every factor in that statute. Adjustment to home, school, and community. Interactions with siblings and family members. Character and circumstance of people around the children. Continuity and stability in the children’s daily lives. All of these considerations can be boiled down to housing questions.

I offer two suggestions regarding kids in DV housing situations. First, having to move due to DV may qualify the children as “precariously housed” under local school district guidelines, even if temporarily. Talk to your clients about reaching out to the school district where the children reside. This can open up options for the children, such as additional bussing to remain at the same school, free or reduced cost meals, and tutoring.

Second, losing your housing as a child can be a traumatic event, especially when combined with DV. Fifteen million children in the United States live in homes where domestic violence has occurred at least once.[xxvii] Daily routine, possessions, privacy, friends, community – all of these can be abruptly gone for a child.[xxviii] There is evidence to show kids who are precariously housed get sick at twice the rate of other children, have three times the rate of emotional and behavioral problems, and are twice as likely to repeat a grade.[xxix]

Sadly, these are things an abuser might use to justify a request for primary custody, even though their abuse created the situation. Encouraging your client to contact Health and Welfare’s Navigation through 2-1-1 or their local domestic violence center for resources that are specific to the children’s physical and mental health can impact potential custody litigation and the children’s long-term wellbeing.

Conclusion

Healthy family relationships are knit together by having a place to be together. If we learned anything from the COVID-19 lockdown, it is that “home” is crucial to our wellbeing and safety. The same goes for people leaving domestic violence situations. As attorneys, asking “What’s the Plan?” and obtaining a legal framework for a family to remain housed together after a DV incident will positively support every aspect of the family’s life going forward.

[i] Managing attorney at Idaho Legal Aid Services practicing family and housing law. Thanks to Fred Zundel and Megan Baiocco for all your help with this article.

[ii] National Network to End Domestic Violence, The Impact of Safe Housing on Survivors of Domestic Violence, https://nnedv.org/spotlight_on/impact-safe-housing-survivors/ (last visited October 25, 2022).

[iii] Id.

[iv] Cris M. Sullivan & Linda Olsen, Common Ground, Complementary Approaches: Adapting the Housing First Model for Domestic Violence Survivors, 43 Housing and Society 182, (2017).

[v] Id.

[vi] Idaho Code § 39-6303.

[vii] National Domestic Violence Hotline, Power and Control, https://www.thehotline.org/identify-abuse/power-and-control/ (last visited Oct. 25, 2022).

[viii] Zach Bruhl, Idaho Sees One of the Highest Rent Increases Nationwide, KMTV 11 (Jul. 6, 2022), https://www.kmvt.com/2022/07/06/idaho-sees-one-highest-rent-increases-nationwide/.

[ix] See Sullivan, supra note 5.

[x] Gaslighting means manipulating someone to the point of him or her questioning reality. Amanda Kippert, A Guide to Gaslighting, https://www.domesticshelters.org/articles/ending-domestic-violence/a-guide-to-gaslighting (lasted visited Oct. 25, 2022).

[xi] Idaho Code § 39-6306.

[xii] Court Assistance Office, State of Idaho Judicial Branch, https://courtselfhelp.idaho.gov/docs/forms/CAO_DV_1-1.pdf (last visited Oct. 25, 2022).

[xiii] I.R.F.L.P. Rule 101 (note that stalking CPOs are covered under the civil rules and not the family law rules).

[xiv] I.R.F.L.P. Rule 811.

[xv] Lease clauses like these can be grounds for a Fair Housing complaint filed with HUD at https://www.hud.gov/fairhousing/fileacomplaint%20.

[xvi] Idaho Code § 39-6306.

[xvii] Monica McLaughlin & Debbie Fox, Housing Needs of Survivors of Domestic Violence, Sexual Assault, Dating Violence, and Stalking, National Low Income Housing Coalition, 2022 Advocate’s Guide, https://nlihc.org/sites/default/files/2022-03/2022AG_6-02_Housing-Needs-Victims-Domestic-Violence.pdf.

[xviii] 34 U.S.C. § 12491.

[xix] Subsidized housing searches in Idaho: https://rdmfhrentals.sc.egov.usda.gov/RDMFHRentals/select_state.jsp, https://resources.hud.gov/, https://www.hud.gov/sites/dfiles/State/documents/ID-Affordable-Apts.pdf, and https://www.thehousingcompany.org/properties/. You can also look up the property on Idaho’s GIS Parcel Maps https://maps.idahoparcels.us/web/ or review the property’s website for subsidy information.

[xx] Women’s Law, VAWA Housing Protections, (last updated September 17, 2021) https://www.womenslaw.org/laws/federal/vawa-housing-protections.

[xxi] Forms available at https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/housing/mfh/violence_against_women_act on the right side of the menu.

[xxii] “A tenancy at will has no fixed terms while a periodic tenancy automatically continues for successive periods.” Caldwell Land & Cattle, LLC v. Johnson Thermal Sys., Inc., 165 Idaho 787, 798, 452 P.3d 809, 820 (2019).

[xxiii] Idaho Code §§ 55-208 and 55-307.

[xxiv] Idaho Code § 6-302.

[xxv] “Ejectment is an action at law that tests the right to the possession of real property as against one who presently possesses it wrongfully. In other words, ejectment is an action filed by a plaintiff who does not possess the land but has the right to possess it against a defendant who has actual possession.” 25 Am. Jur. 2d Ejectment § 1; “The sole issue before a court in [an eviction] proceeding (after determining that a landlord-tenant relationship exists) is the question of who has the right to possession.” Texaco, Inc. v. Johnson, 96 Idaho 935, 938 (1975).

[xxvi] Supra note 19.

[xxvii] Office on Women’s Health, Effects of Domestic Violence on Children, https://www.womenshealth.gov/relationships-and-safety/domestic-violence/effects-domestic-violence-children (last visited Oct. 25, 2022).

[xxviii] Ellen L. Bassuk & Steven M. Friedman, Facts on Trauma and Homeless Children, National Child Traumatic Stress Network Homelessness and Extreme Poverty Working Group, 2005, https://www.nctsn.org/sites/default/files/resources/facts_on_trauma_and_homeless_children.pdf.

[xxix] Id.

Jacob B. Workman is a managing attorney at Idaho Legal Aid Services where he practices primarily family and housing law. He maintains a personal law blog for young lawyers at seegenerally.com.