Latino Learning in Idaho: Far From Equal

Elizabeth Finley

Published November/December 2021

The role of Latino immigrants in Idaho dates back to the early 1900’s when, after the Mexican Revolution, people from Mexico began immigrating to working in mines and agriculture, and building railroads.[1] Today, agriculture is the largest contributor to Idaho’s economy and accounts for 20% of the state’s gross state product.[2] The success of Idaho’s agricultural industry depends on crops being effectively planted, watered, and harvested, and without the help of seasonal migrant and immigrant farmworkers this would be impossible.[3]

In 2018, 85% of Idaho’s Latino population, were of Mexican descent.[4] Some farmworkers immigrate permanently, bringing their families with them.[5] Their children attend school and become part of the fabric of the community.[6] Yet, after years of building the Idaho agriculture industry, the children of Latino immigrants and seasonal migrant workers are still struggling to attain equality in education.[7]

Words from Chief Justice Warren Sixty-four years ago, Chief Justice Warren wrote “it is doubtful that any child may reasonably be expected to succeed in life if he is denied the opportunity of an education. Such an opportunity, where the state has undertaken to provide it, is a right which must be made available to all on equal terms.”[8]

This article will address the history of educational desegregation based on language proficiency and federal education law before looking at a current complaint against an Idaho school district which shows that segregated instruction exists in Idaho and fails to provide the educational equality guaranteed under the law.

Desegregation Cases

The earliest school desegregation case took place nearly a century ago in Lemon Grove California, a small suburban district outside of San Diego.[9] In the summer of 1930, the all-white PTA and school board decided to build a separate and segregated school for the Latino students. And insisted that the Latino students attend this school while the white students were allowed to remain at the regular school.[10]

In Alvarez v. Owen the parents of the Latino children argued that the school board was attempting to segregate their children by not allowing them to attend the same school as their white peers, even though 95% of the students were American citizens. They argued that the board had “no legal right to exclude [. . . the Mexican children] from receiving instruction upon an equal basis [. . .].”[11] The California Superior Court agreed, noting that the Latino children were lawfully entitled to receive equal instruction as the white children under California law.[12] The court demanded an immediate reinstatement of the children.[13]

Early Latino desegregation cases such as Lemon Grove, laid the foundation that equality in education was fundamental to equality in the nation.[14] But, it would take two decades until the Supreme Court would rule on segregation in education.[15] In Brown v. Board of Education the Supreme Court held that separate but equal educational facilities violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.[16]

In 1981, the Fifth Circuit held that when a school failed to provide adequate Language Instruction Educational Programs (LIEP) it discriminated against students whose native language was not English. [17] And a year later, in Plyler v. Doe, the Supreme Court held that denying a public elementary or secondary education to an undocumented person violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.[18]

Thus, under the law, schools must offer equal educational opportunity to all students regardless of race, national origin, or citizenship status; and they must accommodate those students not fluent in English such that those students are able to learn on equal footing as their English-speaking peers.

Words from Justice Brennan Justice Brennan wrote for the majority: “In addition to the pivotal role of education in sustaining our political and cultural heritage, denial of education to some isolated group of children poses an affront to one of the goals of the Equal Protection Clause: the abolition of government barriers presenting unreasonable obstacles to advancement on the basis of individual merit.” [19]

Federal Education Law

Congress solidified the ban on racial discrimination in schools with the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and acknowledged that limited English language proficiency was a barrier to equal educational access with the Bilingual Education Act in 1968.[20] Then, in 1974 Congress passed the Equal Educational Opportunities Act (EEOA) providing that “no state can deny equal educational opportunity on the basis of gender, race, color, or national origin through intentional segregation by an educational institution.”[21]

It provides that intentional segregation includes failing to remove language barriers that prevent participation by non-native speakers, essentially mandating that schools accommodate students by providing adequate resources for students who do not speak English.[22] By including language barriers as intentional segregation the EEOA brought English Learner (EL) students under the wing of Brown.[23]

Federal education law gives discretion to states to implement educational policy.[24] This light touch in many ways is ideal as it allows states and local school districts to respond to needs on a local level.[25] State and local educational institutions are able to set curriculum, providing that the curriculum comply with equal protection and civil rights laws.[26] The constitution granted the Legislative branch the power to make law and the Judicial branch the power to say what the law is.[27] Ultimately though, the state agency regulates the school districts and the local school districts are entrusted to implement procedures that comply with the law.

Wilder School District: A Case Study for the EEOA

In January of 2021, Idaho Legal Aid Services filed a complaint on behalf of four Wilder community members against the Wilder School District with the U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights.[28] The complaint alleges, in part, violations of (1) Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and its implementing regulations, (2) the Equal Education Opportunities Act of 1974, and (3) the English Language Acquisition, Language Enhancement, and Academic Achievement Act, Title III, Part A of the Elementary and Secondary Act of 1965.[29]

Wilder School District (WSD) is a small, majority-Latino district in southwestern Idaho. Agriculture is the primary industry in the area and employs many of the Latinos who live there. In 2020, 69% of Wilder’s 506 total students were Latino, making it the district with the largest percentage of Latino students in the state.[30] English Language Learners (ELL), comprise a third of students at WSD.[31] Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act all Idaho districts are required to provide appropriate education to students whose primary language is not English.[32]

The Complaint and Declarations filed in support of the complaint provides the following timeline and allegations:

In 2016, WSD began using a new program known as “Personalized Learning.” This program made iPads the sole means of instruction for all students in all grades, including ELL students. After the program’s inception it became apparent to the parents of ELL students that the program was not working well for their children. A group of WSD parents, students, and concerned residents began to advocate on behalf of ELL students. The group worried that WSD was not providing adequate instruction to ELL students. The students could not teach themselves independently and needed significant help from teachers. But teachers who voiced concern or offered individual assistance to students were told that they would be looking for work elsewhere if their efforts continued.

During the fall of 2017, about a dozen middle school and high school students were identified as needing ELL instruction and services. Shortly after the start of the school year a newly hired PE teacher was also designated as the district’s ELL teacher. The teacher taught PE in the morning and afternoon but was allotted little or no time to provided ELL instruction.

During the spring of 2018, the staff was notified that students were not receiving legally mandated ELL services. In response, the district directed a classroom aid to assume some of the PE teacher’s PE duties. Students then began to receive some ELL instruction. During the second semester, however, the teacher was placed on leave and the district did not replace her. All ELL instruction ceased.

During the fall of 2018, the district did not renew the previous ELL/PE teacher’s contract and the ELL students received no testing or instruction. The elementary level ELL students were sent to “speak English” with a classroom aid and the middle and high school students were told to buddy up with bilingual students so that the bilingual students could tutor ELL students. Once more, a classroom aid with no ELL certification or instructional experience was supposed to mentor these students.

Also, 7th to 12th grade students identified as ELL were required to spend a certain number of minutes on the “Imagine Learning” (IL) iPad app, an app designed specifically for pre-K to 6th grade students to improve reading skills. No out loud work was done with the program, it was strictly read-and-click. ELL designated students were pulled from class two or three times per week and spent about 20 minutes working with the program and a classroom aid. The only assistance students received with speaking or listening skills was from a classroom aid who had no teaching certification in any subject, let alone ELL. There was no writing component to the IL literacy program. When students needed to write in English, they were instructed to use the Google Translate app to translate their Spanish words to English.

Additionally, the superintendent appointed an elementary school teacher as the ELL coordinator and said that she had provided the necessary ELL training to the WSD staff. The administration sent false emails to the staff regarding these training sessions. However, the coordinator did not provide any ELL training at any point that year. Teachers who attempted to speak out about what was happening were threatened with losing their jobs.

Eventually, the parents received an audience with the school board and were able to voice their concerns. The school board did not help the parents, instead it berated them for bringing their concerns forward.

The parents then investigated the school board election process. The written WSD policy requires the district to file a notice for the nomination and election of school district board members in the newspaper. WSD failed to provide notice as required by the policy; the only notice given to the community was on a single bulletin board at the City Hall. The last election had taken place in 2005.

The parents then took their concerns to the State Department of Education. At the time the State Superintendent, Sheri Ybarra, was running for reelection in the Republican primary against the WSD superintendent, Jeff Dillon. The State Superintendent refused to investigate the complaint, citing a conflict of interest to her reelection campaign. She then referred the parents’ complaint back to the WSD Board. After the return of the complaint to the WSD board the WSD superintendent discovered the names of the individuals who lodged the complaint. Students and parents allege that Dillon retaliated against them by taking recess away, revoking privileges, and threatening expulsion of students and deportation of immigrant parents.

By the end of the 2018-19 school year, many of the veteran WSD teachers had quit or been forced out because they had raised concerns about the IL program and 70% of the remaining teachers in WSD were not credentialed in the subjects they were teaching. Student test scores are illustrative of this effect, with only 20% of K-3 students scoring proficient on a fall reading test, fewer than 20% of high school students scoring proficient in math, and only 48% proficient in English language arts.[33]

The EEOA Applied

The Equal Educational Opportunities Act of 1974 provides in part that “[n]o state shall deny equal educational opportunity to an individual on account of his or her race, color, sex, or national origin, by [. . .] the failure by an educational agency to take appropriate action to overcome language barriers that impede equal participation by its students in its instructional program.”[34]

An “individual” denied an equal educational opportunity may bring a civil action in federal court “against such parties, and for such relief, as may be appropriate.”[35] To be successful, a plaintiff must satisfy four elements: (1) the defendant must be an educational agency, (2) the plaintiff must face language barriers impeding her equal participation in the defendant’s instructional programs, (3) the defendant must have failed to take appropriate action to overcome those barriers, and (4) the plaintiff must have been denied equal educational opportunity on account of her race, color, sex, or national origin.[36]

First, WSD is an educational agency and a Title I school district that receives federal funding; therefore, it must comply with the EEOA.[37] Second, the students are not able to read, speak, listen, and write at a level that will allow for them to understand instruction given in English to a degree necessary to participate equally in educational activities.

The third element of the EEOA test, requiring a showing that the defendant failed to take “appropriate action to overcome those barriers” requires that the educational agency make a “genuine and good faith effort, consistent with local circumstances and resources, to remedy the language deficiencies of their students.”[38] The “appropriate action” language of the statute gives state and local educational agencies latitude in developing programs that would meet the requirements of the EEOA. The Department of Education (DOE) Office of Civil Rights (OCR) applies an analysis devised by the court in Castañeda v. Pickard to determine if a district has complied with the appropriate action requirements of the EEOA.[39]

First, the school must use a sound method “informed by educational theory and recognized by experts,” to teach students. Second, the school’s programs and practices must be “reasonably calculated to implement effectively the educational theory adopted by the school.” Third, the program must produce results that language barriers are “actually being overcome.”[40]

Idaho interprets the first criteria to require that a Language Instruction Educational Program be based upon a sound theory and approach that is proven effective in increasing language proficiency.[41] WSD was using IL as its sole means of instruction for the ELL students. The program did not include a listening, speaking, or writing component. Even if IL is found to be a sound method in ELL instruction, without a speaking, listening, or writing element it is likely not compliant with state or federal regulations.

The second prong provides that the program be implemented with sufficient resources, staff, and space.[42] The US DOE has offered guidance that districts have an obligation to provide necessary staff and if the district provides formal qualifications for that staff, the staff must be qualified or working towards qualification; moreover, a district cannot indefinitely allow staff without qualifications to teach students with limited English proficiency.[43]

Idaho law requires that teachers “shall be required to have a certificate issued under authority of the state board of education, valid for the service being rendered [. . .].”[44] Moreover, under Castañeda “the use of Spanish speaking aids may be an appropriate interim measure, but such aids cannot [. . .] take the place of qualified bilingual teachers.”[45]

In WSD, there were no qualified ELL teachers for at least three school years. In 2017, after receiving a noncompliance notice, WSD employed an ELL teacher, but placed her on administrative leave mid-way through the second semester in 2017 and never replaced her. The only individualized instruction provided to the students was by a classroom aid without a teaching certificate or an ELL certificate. The teacher WSD assigned to be the ELL supervisor in November of 2018 was certified in Social Studies and Spanish, not ELL. He was never trained in ELL instruction. The only professional development WSD offered was when the ELL coordinator (also not ELL certified) sent an email referring him to an ELL website and instructing him to train himself.[46]

By the end of the 2018-19 school year many of the veteran teachers had left the district and 70% of the remaining teachers were not certified to teach the subjects they were teaching. Idaho Law requires that persons who are employed to serve in any elementary or secondary school in the capacity of teacher, are required to have a certificate issued under authority of the state board of education.[47]

The third prong of Castañeda states that if the program fails to produce results showing language barriers are actually being overcome, it fails to constitute appropriate action.[48] Even if the program was implemented in good faith and with sound expectation for success, unless the outcome was a success, the program would not constitute appropriate action.[49] In Castañeda, the program was inadequate in part because the testing of the ELL students was inadequate.[50]

WSD failed to test to measure the program’s progress. Purportedly an entry test existed, however, when the ELL supervisor asked to see the test, he was refused.[51] Thus, there was no baseline to establish performance which could then be used to measure progress. Even if an entry test existed, WSD took no subsequent measures to determine progress. Also, no exit testing existed to establish when and if a student had become English Language Proficient. The lack of testing shows that WSD provided no way of establishing if the program was working. Therefore, WSD has failed to show that actual barriers are being overcome under the third prong of Castañeda.

The fourth requirement of the EEOA speaks to the denial of equal educational opportunities on account of a person’s race, color, sex, or national origin. The court has interpreted the final element of the EEOA to require only a showing of denial of equal opportunity based on race, color, sex, or national origin.[52] Here the complainants have established that the students could not engage meaningfully with IL because they are Spanish speaking Latinos. This is grounds for denial of equal opportunity on race and national origin.

Conclusion

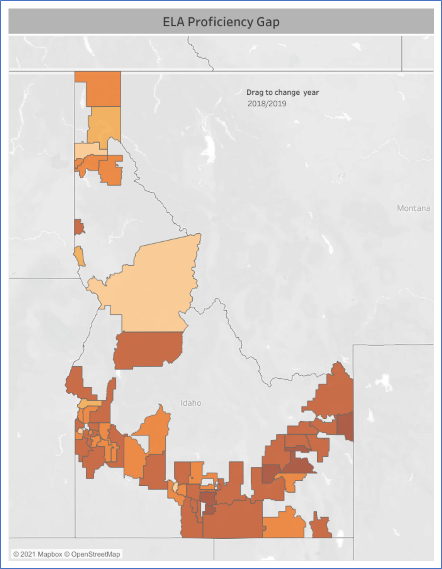

The situation in Wilder, while likely illegal and oppressive, is not uncommon in Idaho.[53] A 2020 investigation into the academic achievement gap between Latino students and white students based on standardized test scores shows disturbing results.[54] Out of 56 districts, 42 had an achievement gap greater than 15%.[55] Many of these districts are located in southern Idaho rural communities where the majority of the Latino population is concentrated.[56]

It has been well over half a century since the landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education, yet Idaho has not honored the intent of the ruling, or subsequent laws passed, to ensure equal educational opportunities for minority students. State and local educational agencies have failed minority students. This failure is most pronounced in Idaho’s rural districts, the same districts which rely heavily on migrant and immigrant workers to ensure their prosperity. It is long past time for Idaho to fulfill its obligation and provide equal educational opportunities for minority students.

“The situation in Wilder, while likely illegal and oppressive, is not uncommon in Idaho.”

Elizabeth Finley is a third-year law student at the University of Idaho College of Law, a Certified Professional Geologist, and a mom of two wild little boys. As an Idaho native raised on a ranch in Owyhee County, she is interested in Idaho policy, civil rights, energy, and natural resources. Liz’s husband and partner of 12 years, Charlie, helps her juggle being a mom and a law student. She enjoys biking, hiking, reading, and hanging with her family.

Endnotes

1 Nicole Foy, ‘We do not like the Mexican.’ Racist chapter of Idaho history revealed by new research, Idaho Statesman (Dec 21, 2019), https://www.idahostatesman.com/news/northwest/idaho/history/article238330788.html

[2] Idaho State Department of Agriculture https://agri.idaho.gov/main/about/about-idaho-agriculture/

[3] Rick Naerebout, Immigrants are vital to Idaho’s dairy industry, Idaho State JournalApril 23,2021. https://www.idahostatejournal.com/freeaccess/immigrants-are-vital-to-idahos-dairy-industry/article_a2ba3496-d9ff-5ad1-bad4-001fa0a3b6bf.html

[4] As defined by the Idaho department of Labor in Hispanic Profile Data Book 5th edition, Idaho Commission on Hispanic Affairs,pg. 39, 55.

[5] Id. at 55

[6] Id. at 110-111

[7] Sami Edge & Nicole Foy, Little accountability for school asked to improve Latino achievement gaps. Idaho ed news.org, Feb. 9, 2020. https://www.idahoednews.org/news/in-high-achievement-gap-schools-plans-for-improvement-are-all-over-the-board/

[8] Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, 493 (1954).

[9] K.L. Bowman, The New Face of School Desegregation, 50 Duke L.J. 1751 (2001).

[10] Robert R. Alvarez, Jr. The Lemon Grove Incident, The journal of San Diego historical society quarterly, Spring 1986, vol. 32, no. 2. https://sandiegohistory.org/journal/1986/april/lemongrove

[11] Id.

[12]Alvarez v. Owen, No. 66625 (Cal. Sup. Ct. San Diego County filed Apr. 17, 1931).

[13] Id.

[14] Robert R. Alvarez, Jr. The Lemon Grove Incident, The journal of San Diego historical society quarterly, Spring 1986, vol. 32, no. 2. https://sandiegohistory.org/journal/1986/april/lemongrove .

[15] Brown, 347 U.S. 483.

[16] Id. at 495.

[17] Castaneda v. Pickard, 648 F.2d 989 (5th Cir. 1981).

[18] Plyler v. Doe, 457 U.S. 202, 210 (1982).

[19] Id. at 222.

[20] Civil Rights Act of 1964, § 7, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e; Bilingual Education Act, 20 U.S.C. § 880b.

[21] The Equal Educational Opportunities Act of 1974, 20 U.S.C.S. § 1703(f).

[22] Id.

[23] ELL students in Idaho are classified according to the Federal government definition as described in the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) Section 3201(5).

[24] U.S. Department of Education, the federal Role in Education, Overview.https://www2.ed.gov/about/overview/fed/role.html

[25] Id.

[26] Idaho content standards English Language Arts/Literacy Manual, pg. 3 https://idahoansforlocaleducation.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/ELA-2018.pdf

[27] U.S Const. art. I, § 1and Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. 137 (1803)

[28] Plaintiff’s Complaint, E.D., C.D., J.D., and J.C., v. Wilder School District. Jan. 27, 2021. https://www.idahoednews.org/news/families-file-discrimination-complaint-against-wilder-school-district/

[29] Id. and 42 U.S.C. §2000d, 34 CFR Part 100, and 28 C.F.R. § 42.104 (b)(2), and 20 U.S.C. §1703(f), 20 U.S.C. §6801

[30] Id.

[31] Id.

[32] Idaho State Department of Education State EL & Title III Program. https://www.sde.idaho.gov/federal-programs/el/files/program/manual/2020-2021-Mini-Manual-State-EL-and-Title-III.pdf

[33] Sami Edge and Nicole Foy, Families file federal civil rights complaint against Wilder district, Idaho Ed News.Org (Jan. 28, 2021)01/28/2021.

[34] 20 U.S.C. § 1703(f).

[35] Id. § 1706.

[36] See 20 U.S.C. § 1703(f) and § 1720(a) (defining “educational agency”).

[37] 20 U.S.C. § 1703(f) and Idaho State Department of Education State EL & Title III program.

[38] Castaneda, 648 F.2d 989, 1011 (5th Cir. 1981).

[39] Internal Department of Ed OCR memo: developing programs for English Language Learners: OCR Memorandum, dated 9/27/1991.

[40] Id.

[41] As laid out by the Idaho State EL & Title III Mini Manual

[42] As laid out by the Idaho State EL & Title III Mini Manual

[43] Internal Department of Ed OCR memo: developing programs for English Language Learners: OCR Memorandum, dated 9/27/1991. https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/ell/september27.html

[44] Idaho Code §33-1201

[45] Castaneda, 648 F.2d at 1013.

[46] Plaintiff’s Complaint, E.D., C.D., J.D., and J.C., v. Wilder School District.

[47] Idaho Code § 33-1201.

[48] Castaneda, 648 F.2d at 1010.

[49] Id.

[50] Id. at 1014

[51] Plaintiff’s Complaint, E.D., C.D., J.D., and E.C., v. Wilder School District, Declaration of CH, pg. 3

[52] Issa v. School District of Lancaster, 847 F. 3d 121, 139 (2017)

[53] Erik Johnson, of Idaho Legal Aid services, attorney for complainants provided that, the DOE is in the process of deciding whether they have jurisdiction over the WSD case. In the meantime, how many more Latino students in need of ELL instruction are marginalized by the lack of an appropriate program at WSD. The school with the largest percentage of Latino students in the Idaho has not had an appropriate ELL program for the past 5 years and counting.

[54] Idaho EdNews Staff, Latino Listening Project wins Education Writers fellowship (Nov. 1, 2019) https://www.idahoednews.org/news/latino-listening-project-wins-education-writers-fellowship

[55] Sami Edge, Maps illustrate learning disparities between white and Latino students (Jan. 3, 2020) https://www.idahoednews.org/news/maps-illustrate-learning-disparities-between-white-and-latino-students

[56] Id.