Incoming President’s Message: Resolutions, the First Amendment, and You by Hon. Robert L. Jackson and Logan Graham

2025 has come to a close and I am sitting at home on a cold afternoon contemplating the new year. I have an article to write, so what better topic than New Year’s Resolutions?

First, before even writing about New Year’s Resolutions, I had to do some checking to see if that is even a task people perform anymore. I enlisted the help of Logan Hansen-Graham, a 2L student at the University of Idaho, to assist with research for this article. His first contribution, as a Gen Z, was to address that question. He assured me New Year’s Resolutions are still a thing. As a baby boomer myself, I know members of that dwindling group still make them. I know many Gen X and Y folks, and some of them make them. I don’t think we have any bar members in the Gen Alpha group yet.

By the time you are reading this article, some of you may have participated in a ceremony to renew your Attorney Oath. That means, presumably, you read the oath. If you have not participated in a recent ceremony to renew your Attorney Oath, why not make that one of your New Year’s resolutions? For those who swore to that oath years or decades ago, let me remind you of what the first two sentences say.

“I Do Solemnly Swear That: (I do Solemnly Affirm That:)

I will support the Constitution of the United States and the Constitution of the state

of Idaho.

I will abide by the rules of professional conduct adopted by the Idaho Supreme

Court.”[i]

A Closer Look at “Support”

Ok, we all, at least at the beginning of our careers, swore or affirmed to “support” two very important constitutions. But, what does it mean to “support” a constitution? The relevant definition found in Black’s Law Dictionary (I still have mine, 5th edition, copyright 1979) is “To vindicate, to maintain, to defend, to uphold with aid or countenance.”[ii] The federal district courts have reached similar interpretations when the word is used in connection to a constitutional oath.[iii]

Because “support” is a verb, it follows that, in order to abide by our oath, we must perform some affirmative action to “support” our two constitutions. What type of action should be taken? The U.S. Supreme Court has asserted that an oath to “support” a constitution creates “a commitment to abide by our constitutional system” and “requires an individual assuming public responsibilities to affirm . . . that he will endeavor to perform his public duties lawfully.”[iv]

Sanctions

What happens if an attorney does not “support” the constitutions? Are there any sanctions? Are there any Idaho Rules of Professional Conduct that provide guidance as to what attorneys should do to cultivate knowledge of the law and employ that knowledge in reform of the law and work to strengthen legal education? Are there sanctions that may be levied upon an attorney who should fail to comply with the mandates of our oath and ultimately our federal and state constitutions?

The Idaho Rules of Professional Conduct may come into play. Comments [6] and [7] in the Preamble to the Idaho Rules of Professional Conduct provide general guidance.[v] I wish I had space to set them out verbatim, but I do not. Please review them. I’d suggest you print them off and have them in a place for quick frequent review.

But there are specific Idaho Rules of Professional Conduct that could potentially be violated when an attorney does not “support” the constitutions. They are Rules 3.1, 4.1, and 8.4(c). Rule 3.1 addresses meritorious claims and contentions. For example, making a clearly unconstitutional claim could invoke Rule 3.1. Making knowingly false statements could violate Rule 4.1. Deceitful conduct could violate Rule 8.4(c).[vi]

It is important to read and understand both the U.S. and Idaho Constitutions in order to know what actions must be taken to support them. While our obligation relates to the entirety of both these documents, this article is specifically focused on the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and Article I, Sections 9 and 10 of the Idaho Constitution, given that the rights within these provisions have made their way into the news a great deal lately.

Amendment I to the United States Constitution states:

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

Article I of the Idaho Constitution states:

SECTION 9. FREEDOM OF SPEECH. Every person may freely speak, write and publish on all subjects, being responsible for the abuse of that liberty.

SECTION 10. RIGHT OF ASSEMBLY. The people shall have the right to assemble in a peaceable manner, to consult for their common good; to instruct their representatives, and to petition the legislature for the redress of grievances.

History

To understand why the rights protected by the First Amendment (and, later, Article I, Sections 9 & 10 of the Idaho Constitution) are considered to be worthy of constitutional protection, it is important to understand the historical context surrounding these rights. The first ten Amendments to the U.S. Constitution (known collectively as the “Bill of Rights”) were drafted in response to concerns about the infringement of individual liberties by the powerful, new federal government which the Founders had created. George Mason, an Anti-Federalist delegate who refused to sign the Constitution because of the lack of a bill of rights, famously declared that he would “sooner cut off his right hand than put it to the Constitution as now stands.”[vii]

Mason’s sentiment—as conveyed in a pamphlet entitled Objections to The Constitution of Government formed by the Convention–soon rallied the states to demand an acknowledgement of the basic liberties secured to the people inviolate from the federal government’s power. The people had known the rule of tyranny, which England had imposed, and stood resolute that such authoritarianism would have no place in the newly formed American government. Mason warned that the powers currently granted to the federal government by the Constitution would “enable them to accomplish what Usurpations they please upon the Rights & Libertys of the People.”[viii] As a result of these concerns, the First Congress created ten amendments to the Constitution for the purpose of enumerating those rights upon which the federal government may not infringe.

Freedom of Speech

Among the rights that those first representatives felt were worthy of protection was that of the freedom of speech, which is embodied in the First Amendment. This guarantee was considered fundamental as Americans had witnessed the oppression, which grows when the right of the people to speak against injustice is quelled by the government. The trial of John Peter Zenger in 1735 was one such example. Zenger was the printer of the New York Weekly Journal, a newspaper that opposed the administration of the British-appointed governor of New York. He was prosecuted by the Crown on the charge of seditious libel—defined at the time as intentionally publishing written blame of a public official or institution. Zenger’s attorney, Andrew Hamiliton, proclaimed his client’s cause as “the best cause. It is the cause of liberty.”[ix] Zenger was only relieved of this injustice by the jury’s “not guilty” decision. The governor whom Zenger had opposed described the case as “the germ of American freedom, the morning star of that liberty which subsequently revolutionized America!”[x] These injustices prompted the ratification of the First Amendment on December 15, 1791.

Since its ratification, the commitment of the American judiciary to upholding the First Amendment has been greatly tested throughout our nation’s history. One of the most memorable challenges was the Sedition Act of 1798. The Act was passed by the Federalist-controlled Congress in an effort to silence opposition to the Adams administration. Under this law, persons who were accused of taking part in “writ[ing], print[ing], utter[ing] or publish[ing] . . . any false, scandalous and malicious writing or writings against the government of the United States” could be criminally charged.[xi] Attorneys of this period faced a difficult struggle in defending those who were charged under the Act. In addition to a hostile political climate towards their clients, these advocates also faced opposition in the courtroom by federal judges who vigorously supported the Sedition Act from the bench. Yet, attorneys opposing those prosecutions stood by the guarantees of the First Amendment in their arguments; upholding their clients’ fundamental right of free speech against the attacks of a political administration seeking to suppress the words of its opponents.

Contemporary Status of the First Amendment

The Sedition Act expired over 220 years ago, yet the danger of undermining the guarantees of our Constitutions lives on. One need only pay even slight attention to the news to appreciate multiple examples of the erosion of those guarantees during the past year. SCOTUS has long recognized that “government has no power to restrict expression because of its message, its ideas, its subject matter, or its content.”[xii] Yet, many modern policy decisions have alluded to a need to silence opposition just as the Sedition Act of 1798 did.

In order to “support” our constitutions, specifically Amendment I of the United States Constitution and Sections 9 and 10 of Article I of Idaho’s constitution, all Idaho licensed attorneys should take some sort of affirmative action.

We, as members of the bar, should not sit idly by like a person watching the floats in a parade pass them. Think of each of those floats representing some form of suppression or deterioration of a constitutional right. Do you just look at it? Do you ignore it? Do you hope someone else takes action to fix it? Attorneys should not be simply observers of the law and constitutional rights. Observers are not supporters. Supporters take some sort of affirmative action. Our Attorney Oath demands it!

Some examples of support could include: working to strengthen legal education by writing articles for the press; participating in moot court; volunteering to teach a class; speaking at a school, a church, or a community group; hosting civic lessons; mentoring; speaking out and/or taking a public position against unconstitutional behavior; attending peaceful protests; participating in elections financially; volunteering time to campaigns or as candidates; accepting appointments by a tribunal; defending individual rights; actively dispelling misinformation about the legal system by correcting misinformation when you hear it in conversations, on social media, or in the broader community; writing an op-ed; engaging in pro bono work to ensure representation for those whose constitutional rights are in jeopardy; or joining organizations that support and protect constitutional principles and civil liberties.

Lawyers play a vital role in the preservation of society.[xiii] We must appreciate that the legal profession plays an important role in preserving government and that our government is a government of laws. I urge you to, if you have not, make a New Year’s resolution to actively support our constitutions!

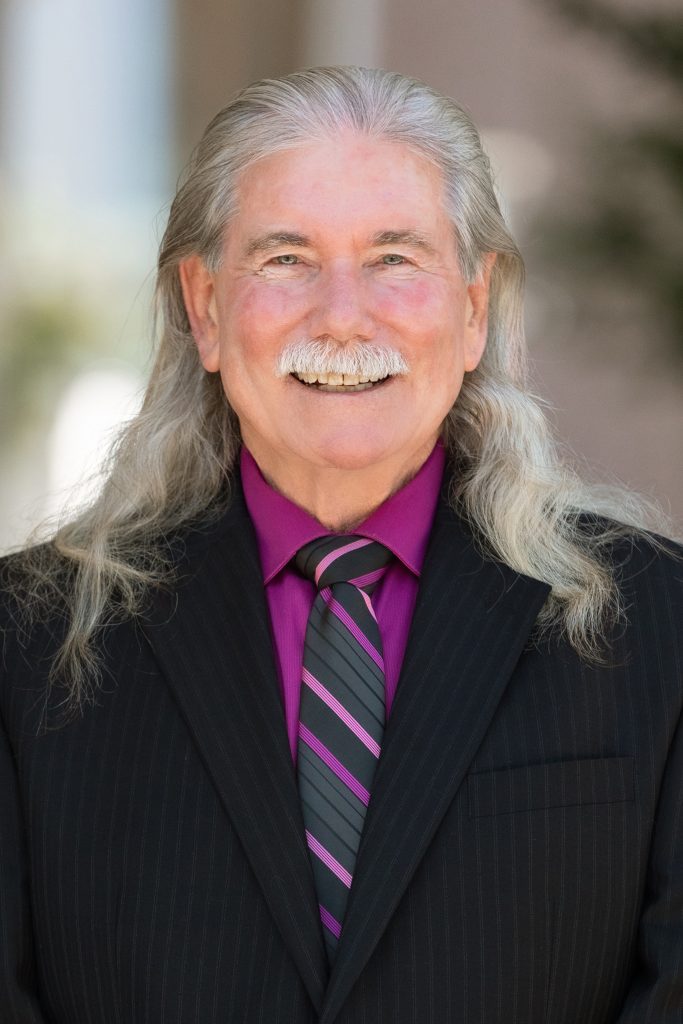

Judge Robert L. Jackson practiced law in Idaho from 1983 until going on the bench as a magistrate in Payette County in August 2013. His varied practice included criminal prosecution, criminal defense, assistant city attorney, personal injury (plaintiff and defense), medical malpractice, insurance law, and workers’ compensation. Judge Jackson also serves as the current Idaho State Bar President of the Board of Commissioners, representing the Third and Fifth Districts. When not engaged in legal work you can find him, with family members or friends, at a concert, hiking, backpacking, farming, or traveling.

Logan Graham is a second-year student at the University of Idaho College of Law. Logan earned his bachelor’s degree in history from Idaho State University and his associate’s degree in political science from the College of Western Idaho. His interests in law include constitutional law, land use, and personal injury.

[i] Attorney Oath, Idaho State Bar, https://isb.idaho.gov/wp-content/uploads/Attorneys-Oath-adaacc.pdf (last visited Jan. 2, 2026).

[ii] Support, Black’s Law Dictionary (5th ed. 1979).

[iii] The federal District Court for the District of Colorado has stated that the definition of “support” is “to actively promote the interests or cause . . . ” and “to uphold or defend as valid.” Ohlson v. Phillips, 304 F. Supp. 1152, 1154 (D. Colo. 1969).

[iv] Cole v. Richardson, 405 U.S. 676, 682-84 (1972).

[v] Idaho Rules of Pro. Conduct Preamble cmt. [6] & [7] (2025).

[vi] Idaho Rules of Pro. Conduct r. 3.1, 4.1, and 8.4(c) (2025).

[vii] Pauline Maier, The First Dissenters, 31 Humanities 6, Nov./Dec. 2010.

[viii] George Mason, Objections to The Constitution of Government formed by the Convention (1787).

[ix] Crown v. John Peter Zenger, 1735, Hist. Soc’y of the N.Y. Ct., https://history.nycourts.gov/case/crown-v-zenger/ (last visited Dec. 31, 2025).

[x] Id.

[xi] Alien and Sedition Acts (1798), Nat’l Archives, https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/alien-and-sedition-acts (last visited Dec. 31, 2025).

[xii] United States v. Alvarez, 567 U.S. 709, 716 (2012).

[xiii] Idaho Rules of Pro. Conduct Preamble cmt. [13] (2025).