Commissioner’s Column : A Tale of Two Courthouses in Nez Perce County by Patricia E.O. Weeks

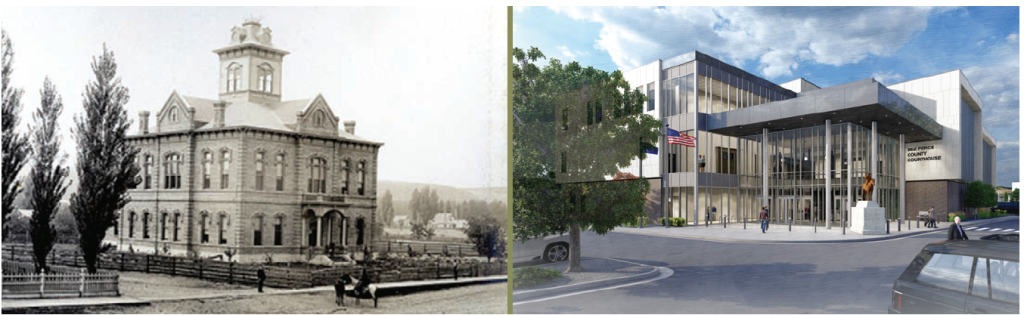

In 1889, the Nez Perce County Courthouse opened its doors in Lewiston, Idaho, with its grand facade and dignified presence, it stood as a symbol of the enduring principles of justice and public service. For well over a century, it bore witness to generations of trials, hearings, and legal proceedings that shaped the lives of Idahoans. However, behind its historic charm lay significant structural, logistical, and safety challenges that increasingly hindered the daily operation of the court system. In 2025, a new courthouse replaced it, ushering in a modern era of accessibility, efficiency, and security.

This article explores the critical role of infrastructure in the administration of justice and why the investment in the new Nez Perce County Courthouse represents more than just a change of scenery, it’s a commitment to the citizens it serves.

Justice Shouldn’t Be a Climb: Accessibility Issues

The grandeur of the old courthouse could not disguise one of its most glaring shortcomings: inaccessibility. The building predated not just the Americans with Disabilities Act (“ADA”), but any modern concept of inclusive design. For individuals with mobility issues, even entering the courthouse or accessing various floors was a challenge.

A striking example of this was documented by the Lewiston Morning Tribune, April 18, 2016, recounting an incident in which a visiting Justice had to climb two small sets of stairs assisted by strong bailiffs just to sit behind the bench. It wasn’t merely inconvenient; it was undignified and unsafe.[1]

Court personnel weren’t immune to the struggle. Staff members navigated steep, narrow staircases to reach a closet-sized breakroom and a single restroom shared among many. It was an exhausting, morale depleting setup, not to mention dangerous in case of emergencies.

By contrast, the new courthouse completed in 2025 meets full ADA compliance. Judges access raised benches via standard ramps. Staff enjoy accessible, modern breakrooms and an adequate number of restrooms. Every corner of the building is designed with inclusivity in mind, ensuring that everyone, regardless of physical ability, can participate in the justice system.

courtroom of the Nez Perce County Courthouse. Photos used with permission and courtesy of

the Lewiston Tribune.

old Nez Perce County Courthouse near a

common stairwell and public hallway. Photo

provided by the author.

When Safety Isn’t Optional: Prisoner and Public Separation

One of the most pressing and less visible concerns in the old courthouse was safety, particularly the lack of separation between in-custody defendants and the public.

There are anecdotes that sound more like scenes from a legal drama than the daily reality of a court. Pressing an elevator button only to be greeted by a group of inmates in chains was not uncommon. Judges and staff occasionally encountered prisoners in public hallways. There was even an instance when a magistrate judge stood at the top of the stairs as eight chained felony inmates exited the only elevator.

The lack of controlled prisoner transport pathways created opportunities not just for disruption, but for real danger. Occasionally, a friend of an inmate would attempt to plant contraband inside the courthouse, hoping the defendant could access it en route to or from the courtroom.

That’s why one of the crown jewels of the new courthouse is its secure inmate transport system. Inmates are brought in through an enclosed sally port, entirely hidden from public view and wait in holding cells. When court is in session, a private elevator delivers them directly to the secure zone between courtrooms, eliminating all contact with the public and courthouse staff. It’s a model of modern security and an essential measure for everyone’s safety.

Hidden Strains: The Human Cost of Inadequate Space

If the public only saw the visible wear of the old courthouse, cracked concrete, red rust from ancient pipes, or unsettling blackened electrical outlets, they might understand why the building was no longer sustainable. What the public couldn’t see was very problematic.

Court staff were practically stacked on top of each other, working in cramped quarters that offered little privacy or comfort. During jury trials, more than 20 court employees were expected to share a single restroom. Hallways were often doubled as storage rooms for the mountain of court files. Some magistrate judges were stationed in remote offices that required them to walk across an open parking lot, exposing them to risk with no immediate security.

These daily indignities affected morale, efficiency, and the professional dignity of those working to uphold the law. The new courthouse corrects all of this with expanded office space, adequate facilities for jurors and staff, and integrated security measures throughout the building.

Infrastructure as a Statement of Values

Courthouses are more than brick and mortar, they are civic monuments that reflect our collective commitment to justice, order, and public service. While nostalgia for historic buildings is understandable, we must not let sentimentality compromise safety, dignity, or efficiency.

The truth is, the old courthouse didn’t stop justice from being served. Cases were heard. Judgments were rendered. The wheels of justice turned, but they turned slower, under strain, and sometimes at the expense of safety, accessibility, and morale.

The new courthouse accelerates those wheels. Now with the state-of-the-art technology, secure courtrooms, and modern infrastructure, the court can now process cases more efficiently and safely. The integration of digital case management, remote hearing capabilities, and better workflow tools has already led to measurable improvements in operations.

Fire codes are met. Technology is up to date. Security is ever present but non-invasive. Staff can do their jobs without physical hardship. Most importantly, everyone from the judge to the janitor to the juror can enter the building with confidence that their needs have been anticipated.

The Public’s Courthouse: Serving Citizens First

Courthouses are one of the last places the public wants to visit. Outside of marriage licenses and passports (love and travel) they are rarely destinations of joy. When people are compelled to walk through those doors, whether as a party to a case, a juror, or a witness, the experience should not add insult to injury.

In many ways, a courthouse is a monopoly. It is the only place where a citizen can access certain essential services, and as such, it carries an obligation to function with the highest standards. Investing in this infrastructure is not a luxury, it’s a civic necessity.

The new Nez Perce County Courthouse is not just a new building; it’s a bold declaration that Idaho values the rights, safety, and dignity of its people. It is a testament to what can happen when stakeholders prioritize infrastructure as a critical component of justice.

Conclusion: A Model for the Future

Nez Perce County’s investment in its new courthouse sets a precedent for other counties facing similar challenges. As court dockets grow, technology evolves, and public expectations shift, aging infrastructure simply can’t keep up.

The move from the 1889 courthouse to the 2025 facility was not merely about aesthetics—it was about aligning our justice system with the realities of the modern world. Accessibility, safety, workflow, and respect for the people who move through these buildings every day, these aren’t optional features; they are fundamental to justice itself.

In the end, the courthouse is more than a building. It’s a promise. In Nez Perce County, that promise has been renewed.

Patty Weeks obtained her Bachelor of Science from Boise State University and Juris Doctor from the University of Idaho, College of Law. She is a licensed attorney in Idaho and Washington and currently the Clerk of the District Court, Nez Perce County. She previously served as an officer and president of the Second District Bar Association and now is a new Bar Commissioner representing the First and Second Districts. She is a lifelong resident of Idaho and lives on the family farm in Reubens.

[1] Lack of Access Is Exhibit A(DA), The Lewiston Tribune, https://www.lmtribune.com/northwest/lack-of-access-is-exhibit-ada-9d6f22a2 (last visited Oct. 3, 2025).