Byron Johnson: The Poetry of a Justice by Jamie Armstrong and Sharla Dawn Robinson Ng

/*! elementor – v3.18.0 – 20-12-2023 */

.elementor-widget-image{text-align:center}.elementor-widget-image a{display:inline-block}.elementor-widget-image a img[src$=”.svg”]{width:48px}.elementor-widget-image img{vertical-align:middle;display:inline-block}

by Jamie Armstrong and Sharla Dawn Robinson Ng

Former Idaho Supreme Court Justice Byron Johnson, who died in 2012, left us with a memory of his goodwill as well as insights into his poetic imagination. In the prologue to Poetic Justice, his memoir published by Limberlost Press in 2011, he stated his writing purpose: “[…] I would like to try to tell how my love of poetry and my search for justice sum up my life.”[i] Near the end of his memoir, Justice Johnson wrote, “Twice each month I get together with a group of poets called the Live Poets at the Log Cabin Literary Center [now named “The Cabin”…]. This is a very nurturing opportunity for me to share my poetry with other serious writers.”[ii] To our group of poets, former Justice Johnson was simply “Byron.”

To honor Byron’s presence in the Live Poets Society (“LPS”), the group included the latter quotation as well as one of Byron’s poems in their recently published anthology. His poem “Part of this Terrain” appears in A Quiet Wind Speaks (2022), an anthology of poems, which celebrates 25-plus years of the Live Poets Society in Boise. In responding to the book, the Editorial Advisory Board of The Advocate stated that an article which discusses Byron’s contribution to the anthology would be of interest to them to consider for publication.

Two of the book’s editors, Sharla and Jamie, are now pleased to share with you our understanding of Byron’s contribution to the poetry anthology. His contribution goes beyond the literal inclusion of one poem and two brief comments from his memoir. In our view, Byon’s contribution to the anthology began with his search for appropriate feedback on his newly written poems. This quest led him to the LPS and a special relationship with the other poets in the group. By presenting the process by which Byron developed himself as a poet in retirement, along with some of his poems, we are sharing with you the foundation of our wish to honor Byron in our celebratory anthology of poems.

Byron’s Initial Poetry Workshops

“In 1997, I concluded that poetry would be my new life.”[iii] And indeed, it was. After Justice Johnson retired from the Idaho Supreme Court in 1999, he made writing poetry a priority. Near and far, Byron actively sought to develop his skills in poetry writing workshops. To prepare for his retired life as a poet, he had written poems, attended local workshops, hosted a workshop in Idaho City, and successfully submitted a poem to a local poetry competition.

After his retirement, Byron explored poetry writing outside Idaho. He was accepted to the Frost Festival, an all-poetry workshop in Franconia, New Hampshire, in 1999, and he returned in 2000. Two years later, he attended the more advanced and selective Frost Seminar. There, he felt humbled to discover many writers who had “been writing poetry seriously for a long time.”[iv] The mindset for writing poetry is different from that of legal writing. If he felt challenged by this elite environment, that would be understandable.

By the time Byron joined the Live Poets Society in 2007, he knew that to grow as a poet he needed “nurturing,” and he was remarkably confident in himself as a human being to say so in his memoir. Since Byron’s passing, Laura Johnson, his daughter, manages his journals and poetry, which he left in her care. Reflecting on her father’s membership in the LPS, she commented on his use of the word “nurturing” to describe his experience with the group. “Nurturing is no small claim for a man such as my father.”[v]

In the epilogue of Poetic Justice, Byron reminds his readers, “I have done my best in these pages to give an accurate portrayal of how poetry and justice have intertwined in my life.” Byron’s memoir contains some of the poems he wrote and workshopped with the LPS. The other Live Poets and Byron served one another well by talking about the content that each poem uniquely expresses and developing the craft of their own poetry.

Give-and-Take Talk with Other Serious Writers

One may wonder just how a poets’ group proceeds with the task of writing poems together. A simple give-and-take model of communication evolved early in the Live Poets’ 25-year history to accommodate the Poets’ wide variety of interests and poem topics (such as moments in nature, interpersonal relationships, and perspectives on society or social issues).

In this communication model, safety and reciprocity are essential features. The give-and-take model involves deep listening. The feedback comes respectfully, each responder knowing that the poet considers their poems to be important and is striving to refine them so that they will be received well by anyone who later hears or reads them. In workshop meetings, there is plenty of praise coupled with occasional gentle suggestions for improvement. This nurturing interaction builds a poet’s confidence and tolerance for feedback. This give-and-take also tends to elicit creative responses from its members.

/*! elementor-pro – v3.18.0 – 20-12-2023 */

@charset “UTF-8″;.entry-content blockquote.elementor-blockquote:not(.alignright):not(.alignleft),.entry-summary blockquote.elementor-blockquote{margin-right:0;margin-left:0}.elementor-widget-blockquote blockquote{margin:0;padding:0;outline:0;font-size:100%;vertical-align:baseline;background:transparent;quotes:none;border:0;font-style:normal;color:#3f444b}.elementor-widget-blockquote blockquote .e-q-footer:after,.elementor-widget-blockquote blockquote .e-q-footer:before,.elementor-widget-blockquote blockquote:after,.elementor-widget-blockquote blockquote:before,.elementor-widget-blockquote blockquote cite:after,.elementor-widget-blockquote blockquote cite:before{content:none}.elementor-blockquote{transition:.3s}.elementor-blockquote__author,.elementor-blockquote__content{margin-bottom:0;font-style:normal}.elementor-blockquote__author{font-weight:700}.elementor-blockquote .e-q-footer{margin-top:12px;display:flex;justify-content:space-between}.elementor-blockquote__tweet-button{display:flex;transition:.3s;color:#1da1f2;align-self:flex-end;line-height:1;position:relative;width:-moz-max-content;width:max-content}.elementor-blockquote__tweet-button:hover{color:#0967a0}.elementor-blockquote__tweet-button span{font-weight:600}.elementor-blockquote__tweet-button i,.elementor-blockquote__tweet-button span{vertical-align:middle}.elementor-blockquote__tweet-button i+span,.elementor-blockquote__tweet-button svg+span{margin-left:.5em}.elementor-blockquote__tweet-button svg{fill:#1da1f2;height:1em;width:1em}.elementor-blockquote__tweet-label{white-space:pre-wrap}.elementor-blockquote–button-skin-bubble .elementor-blockquote__tweet-button,.elementor-blockquote–button-skin-classic .elementor-blockquote__tweet-button{padding:.7em 1.2em;border-radius:100em;background-color:#1da1f2;color:#fff;font-size:15px}.elementor-blockquote–button-skin-bubble .elementor-blockquote__tweet-button:hover,.elementor-blockquote–button-skin-classic .elementor-blockquote__tweet-button:hover{background-color:#0967a0;color:#fff}.elementor-blockquote–button-skin-bubble .elementor-blockquote__tweet-button:hover:before,.elementor-blockquote–button-skin-classic .elementor-blockquote__tweet-button:hover:before{border-right-color:#0967a0}.elementor-blockquote–button-skin-bubble .elementor-blockquote__tweet-button svg,.elementor-blockquote–button-skin-classic .elementor-blockquote__tweet-button svg{fill:#fff;height:1em;width:1em}.elementor-blockquote–button-skin-bubble.elementor-blockquote–button-view-icon .elementor-blockquote__tweet-button,.elementor-blockquote–button-skin-classic.elementor-blockquote–button-view-icon .elementor-blockquote__tweet-button{padding:0;width:2em;height:2em}.elementor-blockquote–button-skin-bubble.elementor-blockquote–button-view-icon .elementor-blockquote__tweet-button i,.elementor-blockquote–button-skin-classic.elementor-blockquote–button-view-icon .elementor-blockquote__tweet-button i{position:absolute;left:50%;top:50%;transform:translate(-50%,-50%)}.elementor-blockquote–button-skin-bubble .elementor-blockquote__tweet-button:before{content:””;border:.5em solid transparent;border-right-color:#1da1f2;position:absolute;left:-.8em;top:50%;transform:translateY(-50%) scaleY(.65);transition:.3s}.elementor-blockquote–button-skin-bubble.elementor-blockquote–align-left .elementor-blockquote__tweet-button:before{right:auto;left:-.8em;border-right-color:#1da1f2;border-left-color:transparent}.elementor-blockquote–button-skin-bubble.elementor-blockquote–align-left .elementor-blockquote__tweet-button:hover:before{border-right-color:#0967a0}.elementor-blockquote–button-skin-bubble.elementor-blockquote–align-right .elementor-blockquote__tweet-button:before{left:auto;right:-.8em;border-right-color:transparent;border-left-color:#1da1f2}.elementor-blockquote–button-skin-bubble.elementor-blockquote–align-right .elementor-blockquote__tweet-button:hover:before{border-left-color:#0967a0}.elementor-blockquote–skin-boxed .elementor-blockquote{background-color:#f9fafa;padding:30px}.elementor-blockquote–skin-border .elementor-blockquote{border-color:#f9fafa;border-left:7px #f9fafa;border-style:solid;padding-left:20px}.elementor-blockquote–skin-quotation .elementor-blockquote:before{content:”“”;font-size:100px;color:#f9fafa;font-family:Times New Roman,Times,serif;font-weight:900;line-height:1;display:block;height:.6em}.elementor-blockquote–skin-quotation .elementor-blockquote__content{margin-top:15px}.elementor-blockquote–align-left .elementor-blockquote__content{text-align:left}.elementor-blockquote–align-left .elementor-blockquote .e-q-footer{flex-direction:row}.elementor-blockquote–align-right .elementor-blockquote__content{text-align:right}.elementor-blockquote–align-right .elementor-blockquote .e-q-footer{flex-direction:row-reverse}.elementor-blockquote–align-center .elementor-blockquote{text-align:center}.elementor-blockquote–align-center .elementor-blockquote .e-q-footer,.elementor-blockquote–align-center .elementor-blockquote__author{display:block}.elementor-blockquote–align-center .elementor-blockquote__tweet-button{margin-right:auto;margin-left:auto}

“I have done my best in these pages to give an accurate portrayal of how poetry and justice have intertwined in my life.”

Fresh ideas readily spring from what is available, like the way legal conclusions are reached when precedent is applied to new fact patterns, or the way new proposals can come to a negotiation table. Furthermore, Live Poets see one another as peers on equal footing. Whether workshopping an individual’s separate poems or working on a group project such as A Quiet Wind Speaks, poets take turns evaluating ideas based on their merits without regard to where they originated or who brought them forward.

For the then-members of the LPS, it was an honor to share their writing lives with Byron, a man whose responses to their poems were informed by deep awareness of the political and social events of the day. His mere presence reinforced the group’s belief that poetry can matter. And Byron consistently behaved as if poetry does matter. Twice a month, he came to each meeting with a poem to share. His responses to others’ poems were encouraging, honest, and helpful.

For example, handwritten onto copies of several of Sharla’s poems from 2011 are his responses which contain these qualities. Three of Byron’s handwritten comments read as follows: “A lesson in letting every day happenings be a source of our poetic inspiration;” “Seems a little stilted in view of other images noted above;” “This causes me to ponder whether it really fits…. I would enjoy seeing a new draft.”[vii] Byron’s gentle and inquiring manner encouraged a mindset of mutual respect that comes with the back-and-forth nature of a give-and-take conversation.

Byron became a dear member of our little community of poets. In the twice-monthly workshop sessions, Byron epitomized what it means to participate in the group’s feedback sessions. He consistently made comments that showed his deep understanding of a poem’s meaning as well as his respect for the poet who had shared the poem. The presenting poet appreciated this kind of feedback from Byron because it meant that both the poet and their poem were taken seriously. By building trust through consistently safe and reciprocal interactions with the other Live Poets, Byron reinforced the group’s give-and-take model of communication. For these reasons and more, the group naturally chose to honor Byron’s memory and poetry in their recent anthology.

Byron’s Poetry

During the five years Byron was a member of the Live Poets Society, he brought poems on a variety of subjects to the workshop meetings: poems about his being in nature,[ix] or about a childhood memory of riding in a neighbor’s sidecar,[x] his Grampa Royal Gold,[xi] or poems from his undergraduate days at Harvard College,[xii] a poem about the cemetery in historic Idaho City,[xiii] or his world travels.[xiv] During his years with the Live Poets, he brought dozens of these poems to workshop at our twice-monthly meetings, including half of the poems that he eventually weaved through the chapters of Poetic Justice.

In this portion of the article, we’ve selected several of the poems in which Byron reveals his essential connection to Idaho’s natural world, where he felt most comfortable with himself, and his spirit felt at home.

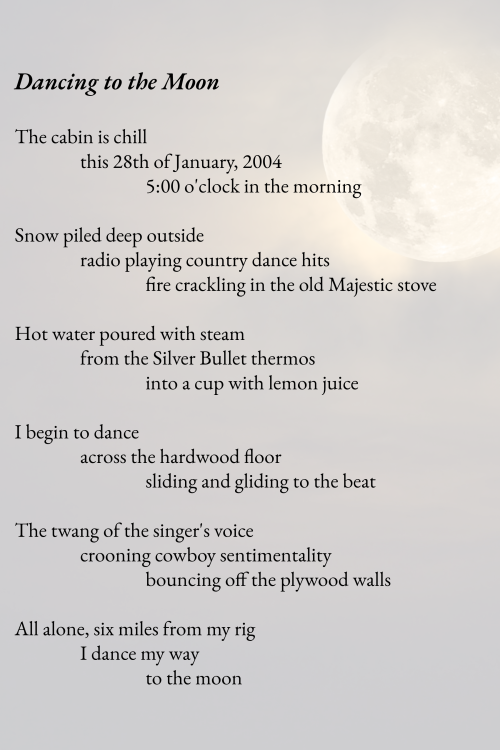

“Dancing to the Moon”

Along with pursuing the craft of his poetry once he retired, Byron also plunged into Idaho’s wilderness. The day after he retired from the Supreme Court, he “skied into Grandjean on the South Fork of the Payette River to spend a month, resting, reading, writing poetry, skiing, soaking in the hot springs, and watching mountain goats and eagles.”[xv] He would return there for his month-long “retreat” each winter through 2006.

Although he thrived on such personal isolation in the wilderness for an extended period each year, Byron the Live Poet was a very relatable person. One near-founding member of the Live Poets Society, Vera Noyce, described Byron’s poetry as indicative of “[…] a gregarious yet solitary individual.”[xvi] One example of this is Byron’s poem, “Dancing to the Moon,”[xvii] which gives readers a peek into this 21st-century mountain man’s cabin and the experience of a joyful moment of dancing alone.

This poem (previously unpublished) tells the story of an unlikely activity for most anyone, let alone a retired justice and lawyer who had presented his serious side to the public while he attended to the serious business of the law. At the unlikely hour of 5 AM, alone and miles from civilization, Byron dances to country music. Then, true to a pattern with which his fellow Poets had become familiar, Byron’s poem ends with a burst of imagination: he decides to “dance [his] way to the moon.” Vera Noyce had this to say about the poem: “I admired and envied Byron’s silent winter retreats in Grandjean where he set his creative juices afire and wrote such lovely poetry. A favorite of mine is his poem ‘Dancing to the Moon’ written in January 2004.”[xviii] Perhaps this poem works so well because it vividly evokes a basic cabin scene and exuberance in a moment of spontaneous dancing.

“My Place in the Universe”

In the first line of his poem, “My Place in the Universe,”[xix] Byron states, “I’m just a mountain man at heart.” Within this line, he found the title for Chapter Eight in Poetic Justice: “Mountain Man.” In the first five stanzas of this poem, Byron asserts his heart’s love of mountain settings. He states what he loves about camping there, which includes bringing in water, building a fire, and pitching a tent. These activities he calls the “necessities of life.” Sitting by his campfire, he can think in peace, listen to the morning songs of birds, or watch the acrobatics of squirrels – all of which keep him from having to think about “worldly affairs.”

The poem ends with this four-line stanza (forward slashes indicating line breaks): “Where else but the mountains/ can you feel so close to the presence/ of whatever it is, in which we live,/ and move and have our being.” In this kind of special moment, when human beings “have our being,” we may experience fulfillment in the profound knowledge that we belong right where we are in the universe and are at peace with ourselves. This concluding stanza begins with the words “Where else,” a phrase that usually starts a question. Yet in this instance, Byron does not end his poem with a question mark; rather, he completes the poem with a declaration that he thrives in the mountains where he knows he is a part of everything.

“My Soul Is Flowing in this River”

When Byron wrote “My Place in the Universe,” he was speaking from the perspective of a lifelong connection to the mountains that had begun in the summers of his youth. Camping with his grandparents on the South Fork of the Payette River, he began to build an intimate relationship with the natural world in the wilds of Idaho’s mountains. Decades later, Byron revealed what these times meant to him: “The South Fork is where I feel most at home and at peace with myself.”[xx] With these words of introduction early in his memoir, Byron presented his poem, “My Soul Is Flowing in this River.”[xxi] Referring to “My Soul” in the title, the poem’s first lines say, “it echoes in the river’s roar/ rolling over rocks worn smooth/ by time’s eternal rush.”

Near the poem’s beginning, Byron expresses a reverential and sacred relationship to the river when he says, “you baptized me” even as he addresses the river as “mother-father.” This river will ultimately hold his soul, which he calls “the essence of my being.” His soul being held in the river’s “everlasting flow” after his death echoes the river’s action of cuddling Byron when he was a youth.

His being held in the river’s flow, a kind of liquid urn for his ashes, also echoes the sense of the all-embracing presence “of whatever it is” that Byron felt in the mountains, which he expressed in “My Place in the Universe” (discussed earlier). Through sharing poems about this intimate aspect of his life in the wild, Byron revealed his trust in people close to him as well as of the general reading public.

“Idaho Needs Poets More than Judges”

Laura Johnson spoke about one poem in particular, “Idaho Needs Poets More than Judges,”[xxii] which showed her father’s “… intent in shifting his life’s focus from the Law to being poetic; and his profound love and respect for Idaho–its natural spaces, its wildlife, its people. “[xxiii]

The last portion of Byron’s poem conveys his reasons for turning “to poetry after the Court:” “Idaho calls poets softly/ to see/ her early morning meadows/ with dew drops on the camas/ to hear/ her rampant rivers/ tumbling over rugged rocks/ to smell/ her pungent pines/ drifting on evening breezes.” He concludes the poem with this stanza: “Idaho needs poets more than judges/ to protect her innocence/ from plunder.” In these lines, Byron personified the wilderness. He speaks as a poet, and his strong “mountain-man” inclination to protect nature is expressed openly. This stance reinforces our understanding of part of his motivation to write poetry after the law.

From sitting by his campfire where he watched life around him to imagining his soul flowing in the Payette, through his poetry Byron revealed his keen abilities of observation. He also expressed his deep, abiding connection to the wilderness regions of Idaho and his certainty of its ongoing importance to all her citizens. Taken together, the previous four poems show the complex, lifelong connection that Byron developed with Idaho’s wild places.

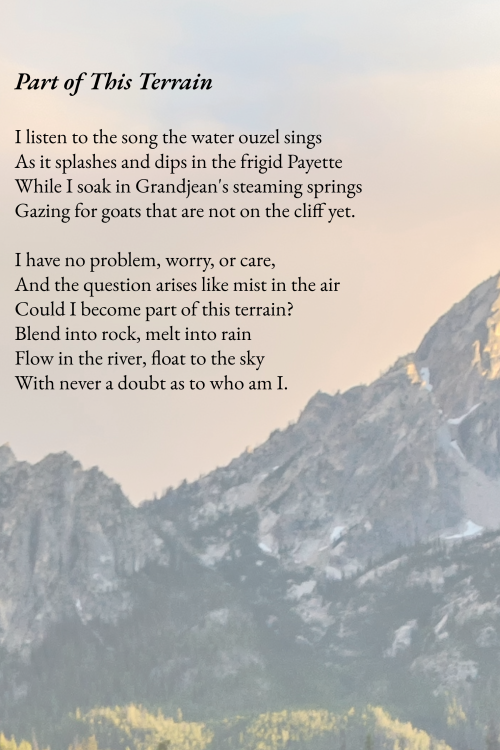

“Part of This Terrain” in A Quiet Wind Speaks

Byron often liked to soak in the hot springs after a day of skiing and other activities each winter when he spent a month in the wilderness. He enjoyed the enervating warmth of the water that relaxes most of the body while one’s head is stimulated by the chill of the surrounding winter air. During such a generative moment, “Part of This Terrain”[xxiv] came to Byron. His eyes scanned the terrain and sky for signs of wildlife as he listened to the sounds of water and the wind. While the smooth rock of the hot springs cradled his being, his mind was set free to wander, reflect, and imagine.

In this poem, while taking care of himself in the wilderness, Byron reveals his core connection with Idaho’s wild places where he could observe the mountains, rivers, and wildlife. While completely absorbed in nature, he clearly states that he knows who he is, his identity as a human being.

As in many anthologies, the poems in A Quiet Wind Speaks were not constrained by or prescribed to a particular theme. Rather, each poem stands unique among the other unique poems, like a forest scene populated with various natural elements who belong together in the environment. In “Part of this Terrain,” a well-crafted poem, Byron expresses something essential about himself in nature, so the Live Poets selected it for inclusion in A Quiet Wind Speaks.

Byron’s Wake

On January 6, 2013, the family and friends of Byron gathered at the recently completed events center in Barber Park on the Boise River for “A Wake Celebrating the Life of Byron Johnson, 1937-2012.” The printed memento for the occasion included two of Byron’s poems, one of them being “Part of this Terrain.” Those assembled were touched by feelings of loss in Byron’s absence. At the same time, we were buoyed by feelings of appreciation of Byron’s life and our joy to be in it with him for as long as we had known him. It felt good to be gathered with people who felt close to him.

Byron loved a good party, as evidenced by the abundance of food, drink, music, readings, and good cheer at his wake. After all, this one was the real thing. Three “practice wakes” (wake-style gatherings in honor of Byron’s life as if he were dead) had occurred for Byron at various times during previous years.

row: Dee Gore, Jamie Armstrong, Tish Thornton.

That Byron loved a lively party was also evident in the way Byron had joined in at the annual Christmas party, which the Live Poets celebrated at The Cabin on the first Wednesday in December for many consecutive years. In a personal comment,[xxv] Vera Noyce recalled the ways that Byron livened up those parties with his refreshments and good cheer: “Byron entered enthusiastically into the festivities, introducing the group to and providing us with outstanding hot buttered rums. His toast at the 2010 party celebrated friendship. It reads, in part:

…to toast poetry and poets

who fill our lives up

The warmth of friendship

comforts us between sips

of this delicious elixir

through poetic lips.

It also was Byron’s kind presence and warm friendship that the Live Poets honored by including one of his poems in our book. In this way the Live Poets continue to toast the memory of Byron Johnson.

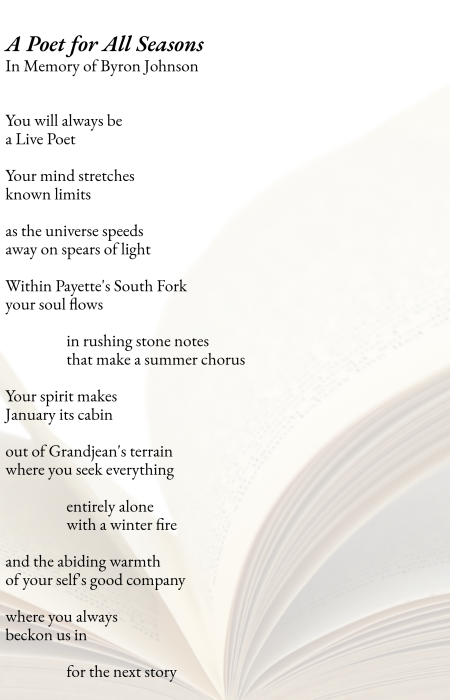

At Byron’s wake, Jamie presented a poem that he had written in memory of Byron, to celebrate his life. In “A Poet for All Seasons,” there are references to Bryon’s poems, “My Soul Is Flowing in this River” and “Part of this Terrain,” which were discussed earlier in this article.

From attorney to Idaho Supreme Court Justice to poet, Byron Johnson had a presence among the Live Poets, which was as natural and evolving as the Idaho wilderness he loved. He remained remarkably open to empathy for the people he encountered along the way. This capacity came through in his poems and enriched the poetry workshop experience for the members of the Live Poets Society. More than 11 years after his death, the group continues to recall Byron’s way of being in the group, his goodwill, and the uniquely personal way his imagination invited the reading public into his trust. As a tribute to Byron Johnson, in gratitude for his being with us, we made an honored place for him in the Live Poets’ 25th anniversary anthology of poems.

NOTE: Copies of Byron Johnson’s memoir, Poetic Justice, may be purchased through the book’s publisher, Limberlost Press at www.limberlostpress.com. Attorneys with Idaho State Bar numbers may check out a copy of the book from the Idaho State Law Library.

/*! elementor – v3.18.0 – 20-12-2023 */

.elementor-widget-image-box .elementor-image-box-content{width:100%}@media (min-width:768px){.elementor-widget-image-box.elementor-position-left .elementor-image-box-wrapper,.elementor-widget-image-box.elementor-position-right .elementor-image-box-wrapper{display:flex}.elementor-widget-image-box.elementor-position-right .elementor-image-box-wrapper{text-align:right;flex-direction:row-reverse}.elementor-widget-image-box.elementor-position-left .elementor-image-box-wrapper{text-align:left;flex-direction:row}.elementor-widget-image-box.elementor-position-top .elementor-image-box-img{margin:auto}.elementor-widget-image-box.elementor-vertical-align-top .elementor-image-box-wrapper{align-items:flex-start}.elementor-widget-image-box.elementor-vertical-align-middle .elementor-image-box-wrapper{align-items:center}.elementor-widget-image-box.elementor-vertical-align-bottom .elementor-image-box-wrapper{align-items:flex-end}}@media (max-width:767px){.elementor-widget-image-box .elementor-image-box-img{margin-left:auto!important;margin-right:auto!important;margin-bottom:15px}}.elementor-widget-image-box .elementor-image-box-img{display:inline-block}.elementor-widget-image-box .elementor-image-box-title a{color:inherit}.elementor-widget-image-box .elementor-image-box-wrapper{text-align:center}.elementor-widget-image-box .elementor-image-box-description{margin:0}

Jamie Armstrong

Jamie Armstrong co-founded the Live Poets Society in Boise. His poems appeared in The Cabin’s Writers in the Attic. As an education professor at Boise State, he received an Idaho Humanities Council grant for Culture of the Irrigated West, a video featuring seven of his poems. Retired, Jamie lives in coastal northern California.

Sharla Dawn Robinson Ng

Between periods of employment at the Idaho Industrial Commission, Sharla Dawn Robinson Ng wrote poetry for creative expression, joining the Live Poets Society in 2010. In recent years she has led their meetings and readings. As editor of AQWS, she’s learned that the group’s give-and-take model of communication encourages generative and kindhearted discussion.

[i]. Byron Johnson, Poetic Justice: A Memoir, 1 (1st Edition, 2011).

[ii]. Id. at 237.

[iii]. Id. at 228.

[iv]. Id. at 230.

[v]. Email from Laura Johnson to author Jamie Armstrong, May 21, 2023 (on file with author).

[vi]. Byron Johnson, Poetic Justice: A Memoir, 239 (1st Edition, 2011).

[vii]. Comment by Byron Johnson, Live Poet, to author and Live Poet Sharla Robinson Ng, July, 2010; March, April, May, 2011(on file with author).

[viii]. Email from Vera Noyce, Live Poet, to author Sharla Robinson Ng, May 9, 2023 (on file with author).

[ix]. Byron Johnson, “My Soul Is Flowing in This River” in Poetic Justice: A Memoir,17 (1st Edition, 2011); Id., “Part of this Terrain,” at 215.

[x]. Id., “The Sidecar,” at 10.

[xi]. Id., untitled poem at 51-52.

[xii]. Id., untitled poem at 31, On His Sight, at 34, untitled poem at 37.

[xiii]. Id, “Gold Rush Cemetery,” at 164.

[xiv]. Id., “Denali Pass – 18,300 Feet,” at 219-220; “The Grande Traverse,” at 221-222; “Images Of China – 2002,” at 223-224; “Namaste, Infinite India,” at 235-236.

[xv]. Byron Johnson, Poetic Justice: A Memoir, 229 (1st Edition, 2011).

[xvi]. Email from Vera Noyce, Live Poet, to author Sharla Robinson Ng, May 9, 2023 (on file with author).

[xvii]. Byron Johnson, Dancing to the Moon (unpublished poem) (on file with author).

[xviii]. Email from Vera Noyce, Live Poet, to author Sharla Robinson Ng, May 9, 2023 (on file with author).

[xix]. Byron Johnson, Poetic Justice: A Memoir, 213-214 (1st Edition, 2011).

[xx]. Id. at 17-18.

[xxi]. Id.

[xxii]. Byron Johnson, Poetic Justice: A Memoir, 227-228 (1st Edition, 2011).

[xxiii]. Email from Laura Johnson to author Jamie Armstrong, May 21, 2023 (on file with author).

[xxiv]. Byron Johnson, Poetic Justice: A Memoir, 215 (1st Edition, 2011).

[xxv]. Email from Vera Noyce, Live Poet, to author Sharla Robinson Ng, May 9, 2023 (on file with author).