Month: June 2019

Federal Bar Association Tri-State Seminar- September 26-28 (Sun Valley)

Registration is now open for the Federal Bar Association’s (FBA) Tri-State conference, which is being hosted by the Idaho Chapter this year. The FBA’s Tri-State Conference is an annual seminar, which rotates among Sun Valley, Idaho; Park City, Utah; and Jackson Hole, Wyoming. It was started fifteen years ago by then Chief Judges Dee Benson (Utah), Bill Downes (Wyoming), and Lynn Winmill (Idaho). The conference addresses a wide range of timely topics with the objective of discussing issues that affect western states, providing opportunities for the FBA members of the three chapters to meet fellow federal practitioners, federal judges and other dignitaries in an informal setting. This year 16 federal judges and court executives will be in attendance.

Program Agenda

Registration form

We look forward to seeing you in Sun Valley. Please contact Susie Headlee at (208) 867-8169, or sheadlee@parsonsbehle.com if you have any questions.

Hutch High’s David Cooper: Putting life’s pieces back together

By Brett Marshall, Staff Writer

On the surface, 18-year-old David Cooper appears to be just another typical high school basketball player. After all, he’s not a starter on the undefeated Hutchinson Salt Hawk team. As a 6-2 senior forward, Cooper comes off the bench to spell one of the HHS frontline staters. He doesn’t score a lot – he averages just four points.

But David Cooper is a special player for this Hutch High team.

“He continually amazes me with how we he has his life together,” said HHS coach Dan Justice of David. “He even teaches me a lot with out he handles himself.”

David, you see, suffered a tragedy last June that few people experience. His father and mother, George and Wilma Cooper, his older brother, Guy, and an older sister, Leslie Lehman, all drowned in a flash flood June 14, 1981, in the Pedernales River in East Central Texas near Johnson City.

David, along with his sister-in-law, Patty Coleman, who was married to Guy, witnessed the tragedy. To this day, it is a tragedy that David cannot, and will not, forget. But it is an event he will discuss without hesitation.

“Since I was there from the moment it happened, I was able to tell myself that there is nothing I can do … I just have to go on.”

Text cut off; picks up at the following:

“…wall built around me and I didn’t want to think about it. But then I gradually snapped out of it and now it doesn’t bother me to talk about it.”

In order to collect social security benefits, David had to enroll in 12 hours of college classes at Hutchinson Community College. That came when legislation under the Reagan administration, due to go into effect May 1, was passed recently.

As a result, David attends four hours of high school classes daily, Monday through Friday. On Monday, Wednesday and Friday, he is in college classes from 1-3 p.m. Wednesday and Thursday nights he has classes from 7-10 p.m.

In between, he practices basketball daily. A busy schedule, indeed.

“So far it’s not too bad,” says David. “I didn’t take too many hard classes at the junior college. The high school classes aren’t that bad either. Wednesday is the only day I have to squeeze everything in.” David doesn’t mind the hectic schedule though.

“I don’t have anything on weekends so I can still maintain a social life and that’s important to me,” says David. “Before basketball season started, I would be bored after school was out. Going to college has helped me with my study habits. I’m sure it will be a big help when I go off to school next fall.”

On the basketball floor, however, David is able to erase thoughts of a busy schedule.

Text cut off; picks up at the following:

“I wasn’t sure how much I was going to get to contribute. Coming off the bench like I do, I feel I must do something while I’m in there, not just take up space. There’s no use playing if you don’t contribute. If you do something worthwhile, your teammates have confidence in you and your ability.” David considers his defense and shooting to be his strengths.

“I love to come in and play good defense and help the team out,” he says. “My shooting is a little streaky. Some nights I can’t miss and other nights I can’t make a thing.”

David doesn’t consider himself to be anybody special just because of what he’s accomplished under…

Text cut off; picks up at the following:

“My parents raised us to be independent as much as possible,” says David of his father and mother. “That was a key factor for me. I was already independent before. Patty has been a big help to me. I prayed a lot and that gave me strength.”

David talks of the accident, which at the time seemed endless to him.

“There were hours of waiting,” he recalls. “I could feel how terrified they were, especially my mom. She was scared of water.”

A helicopter was called in to help in the rescue of the Coopers, but it arrived 10 minutes too late.

“There wasn’t much anybody could do; it’s just one of those things,” David says in retrospect. David now lives with the Lyle Neville family. Neville is the HHS wrestling coach. His son, Lane, is a close friend to David.

“They approached me about living with them and it seemed like a good thing to do,” he says. “They’ve been great to me. I couldn’t ask for anybody to treat me any better than they have.”

David has no reservations about the way he has pieced his life together.

“One thing that makes me feel good is that I think I’ve acted the way he’d [David’s father] want me to,” says David. “He was a psychologist and he taught me how to handle things. I told my parents a year ago that I thought I had been brought up really well,” David says. “The way I’ve handled things is a credit more to them than it is to me.”

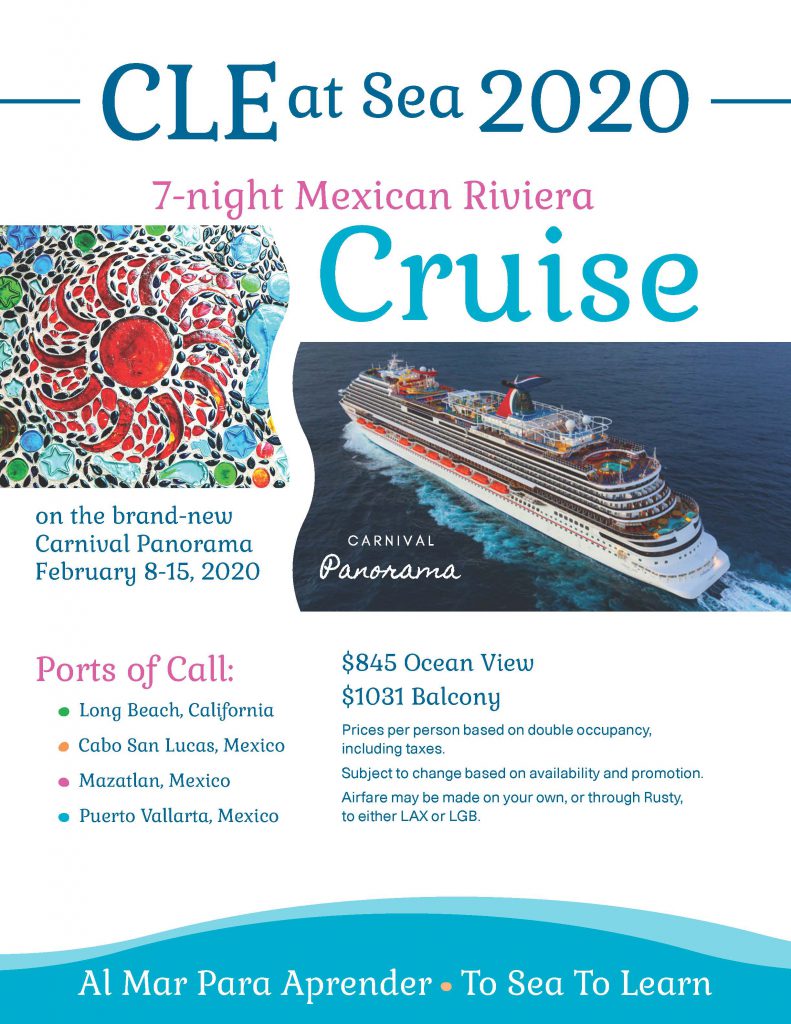

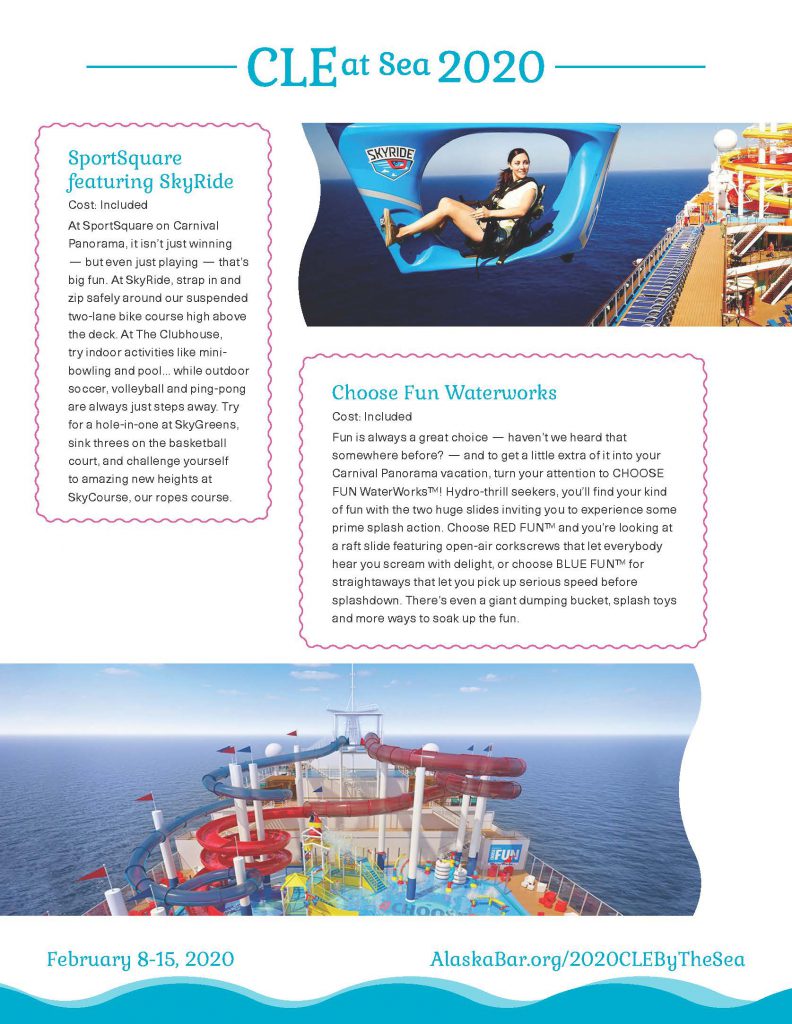

CLE at Sea – February 2020 – Early-bird Registration Ends Nov. 1

New Website Not Compatible with Internet Explorer

Due to the use of new coding technology, several pages on the new version of our website are no longer compatible with Internet Explorer. If you use Internet Explorer and come across a web page that is not displaying properly, please close out of the browser and open the page in a different internet browser. Other browser options include Google Chrome, Microsoft Edge, Safari, or Firefox.

Thank you for your understanding! We apologize for any inconvenience.

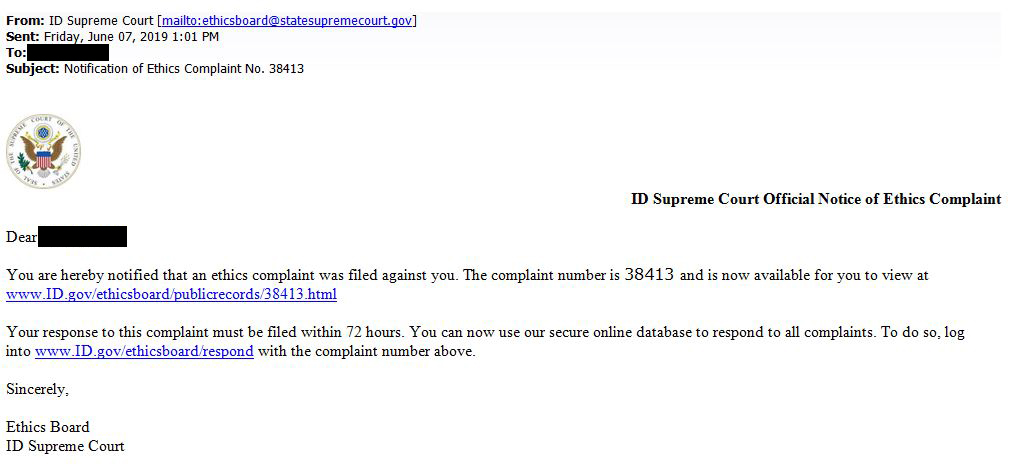

Email Scam Alert – Email posing as Ethics Board & Idaho Supreme Court

It has come to our attention that another email scam is circulating. The email poses as the Ethics Board of the Idaho Supreme Court, claims that an ethics complaint has been filed against you, and requires you to click a link to respond to the complaint within 72 hours. If you receive an email that resembles the example below, it did not originate from Bar Counsel’s Office or the Idaho Supreme Court. DO NOT reply to the email or click on ANY links. Permanently delete the email immediately.

As a reminder, you can often times identify an email as a scam by looking at the sender’s email address. If you do not recognize the sender’s email address or think it may look suspicious, always err on the side of caution and do not click on any links or attachments included in the email.

A Diversity Barrier: Harassment in the Practice of Law

By Bobbi K. Dominick

Much has been written about promoting diversity in the legal profession.[i] Intense focus has centered around women, but the goal of diversity is to encourage, support, and assist those with many diverse backgrounds to enter, and excel, in the legal profession. This includes diverse backgrounds and experiences such as national origin, race, religion, disability, age, and orientation. Organizations that promote diversity and inclusion perform better, achieve better results, and have increased employee engagement.[ii] Diversity increases the bottom line of organizations.[iii] Diversity is an issue worthy of our attention, for economic reasons, as well as the overall goal of improvement of the legal profession.

What are the barriers to increased diversity within the legal profession? A recent report examining female attrition stated this issue succinctly: “[O]ne of the most pernicious hurdles to achieving a satisfying legal career is the unfortunate and continuing problem of sexual harassment.”[iv] This article will examine sexual harassment as a barrier to diversity and provide thoughts for improving diversity.

Harassment is Just One of Many Barriers to Diversity in Law

Recent Advocate articles provide an excellent summary of statistics on female attorneys in Idaho,[v] and bias and its potential impact upon the advancement of women in law.[vi] Those articles, and other research,[vii] point to numerous factors contributing to women leaving the profession or not advancing to positions of greater authority. Some factors may be purely personal choices on the part of individual attorneys who choose a different career or life path. But some reasons for women and minorities leaving the practice may be within our control, and eliminating harassment as a barrier is one of them.

Harassment in the Legal Profession: Statistics and Surveys

A discussion of the impact of workplace harassment must start at the beginning. How prevalent is harassment in the legal profession? Statistics are sporadic and often hard to find, especially if we focus solely upon Idaho.

First, those in protected classes are clearly underrepresented in the law, and thus often in the minority. The articles referenced above cite statistics about women (in Idaho, 28% of attorneys are female, nationally the number is 36%). Statistics nationally indicate a low percentage representation for attorneys with disabilities (perhaps as low as 7%),[viii] those of Hispanic origin (9.9%), Black (5.5) and Asian (4.9).[ix] Since these groups are underrepresented does this mean that they are more susceptible to harassment? According to the EEOC’s recent study of workplace harassment, it does.[x]

Another important point from the recent study: “[w]hen the target of harassment is both and member of a racial minority group and a woman, the individual is more likely to experience higher rates of harassment than white women. Moreover, when the target of harassment is both a member of a racial minority group and a woman, the individual is more likely to experience harassment than men who are members of the same racial minority group.”[xi] While the research is sparse, the same is likely true of those who are members of more than one protected class.

Other states have conducted surveys to discover the prevalence of harassment. For example, a 2005 California survey found that 50% of female attorneys reported experiencing sexual harassment.[xii] The Florida Bar’s study found that 17% had been subjected to harassment based on their gender.[xiii] Utah’s 2010 survey revealed that 37% of women attorneys responding had experienced verbal or physical behavior that created an offensive work environment. Of those, 86% identified gender as the basis for the harassment.[xiv]

As you can see, there is a wide swing in the numbers. Some of that may be attributable to the way the word “harassment” is defined, the way survey questions are worded, or individual nuances in the responder’s understanding of harassment. As the EEOC study noted, the numbers who reported harassment rose when the questions included gender demeaning and derogatory behavior.[xv]

Despite the difficulty of interpreting these statistics and applying them to the Idaho experience, several things are certain:

- Harassment does exist,

- It likely exists in legal practice in Idaho, and

- It is a barrier to women and minorities thriving.

Harassment in the Law: What Kinds of Behaviors are We Talking About?

Harassment that doesn’t involve propositions or sexual language can still form a barrier to diversity. The EEOC has said: “harassment not involving sexual activity or language may also give rise to Title VII liability…if it is ‘sufficiently patterned or pervasive’ and directed at employees because of their sex.”[xvi] Social science research indicates that mistreatment and incivility, whether it rises to the level of illegal harassment or not, can lead to the same kind of harm as harassment, and creates a barrier to advancement.[xvii] Research also tells us that those subjected to this kind of treatment often respond by leaving the organization.[xviii]

Recent surveys and stories have detailed other types of harassment that female attorneys have been subjected to, often not even the typical sexual propositions, but rather demeaning comments and behavior.[xix] Examples that women have shared with me, or that have appeared in articles or case law, include bringing a female attorney into the courtroom as “window dressing,” because “witnesses prefer young and pretty,” or it would be good for “the jury to see a pretty face.” Other examples might include comments made about lipstick, clothing, body parts, makeup and hair, directed only towards women, implying a sexualized or diminished view of the person and their capabilities. Jokes about women could be demeaning, like using #MeToo as a punchline, or comments about women succeeding by “sleeping with the judge,” implying that women cannot advance on their own merits without using gender as an advantage. Comments about women not being serious about their legal careers because they want to have babies and start families also fall into this category (speaking from personal experience). Other micro-aggressions might include labeling women’s behavior as “bitchy” or “aggressive,” or cautioning against being “naïve” or “weak.”

Harassment based on race, national origin, religion, disability is often this kind of “negative stereotype” harassment. Behavior, comments, or attitudes that make a particular class of people feel unwelcome, unappreciated, or unrecognized discourages them from remaining in a profession or organization. Examples might include using pet names, interrupting or ignoring, or dismissive comments. These types of behaviors impede diversity and prevent the advancement of women and minorities.

We Don’t Have a Problem, Do We?

Many legal professionals reading this article may think to themselves: “well, this is all theoretical, because we don’t have a problem in our organization.” That type of thinking is naïve at best and damaging at worst. Research indicates that every type of profession may experience protected class harassment.[xx]

The EEOC consulted with experts and examined what types of organizations are most at risk for harassment. Some of the risk factors clearly apply to legal organizations:

- Homogenous workforce: Ironically, when an entity is made up of primarily one gender (or other protected class, that makes the organization more susceptible to harassment, and the legal profession, based on the above statistics, clearly falls into this risk factor.

- Workplace “norm” dependent environments: When the written or unwritten norms for how people must “behave” tend to favor the dominant class, those who do not meet those norms are harassed at higher rates. This could affect women, but also those with disabilities, different national origins, different religions, and different orientations.

- Power disparity environments: A high power or valuable asset, like a rainmaking senior partner, offers a power disparity that creates a higher risk of harassment.

- Client satisfaction factors: When the environment is client dependent, there is a higher risk of harassment, because bad client behavior may be tolerated or even condoned. [xxi]

Another common misconception: “no one has complained, so it may be happening elsewhere, but not here.” But the statistics tell a different story. The vast majority of those who are subjected to harassing behavior do not complain at all. For many, the solution is to put up with the behavior, minimize the seriousness of it, try to ignore it, or simply to leave that environment.[xxii] This not only damages the diversity of that particular organization but also can be a setback to career advancement for the individual who leaves.

Even when someone does complain, those in a position to respond may not act. This happens for many different reasons. Perhaps most common is that the person to whom the individual complains views the behavior from a different lens, and may not see the harmfulness of the behavior. Other common reasons the behavior might be ignored include the high value of the offender, the difficulty of resolving conflict in the workplace, or perceptions of the person complaining (i.e., questioning motives for complaining, etc.) Another common reason is that there is no process in place in many legal organizations (especially smaller ones) to address complaints, so leaders simply don’t know what to do.

So What Do We Do About This? Some Suggestions

Study and Prevention

A current survey and study should be conducted on harassment (all protected classes) in the legal profession in Idaho.[xxiii] While we know from statistics in other professions that harassment likely exists, we need to know the types of issues we are dealing with specifically in Idaho. Our professionalism efforts should also help lawyers focus upon effective human resource management, including both diversity and harassment prevention.

Internal Organizational Efforts

At a minimum, each legal organization in Idaho could assess the impact of harassment within their organization and develop strategies for removing this diversity barrier diversity. Every law firm and legal department should engage in proactive efforts to raise the level of concern about harassment that might be occurring, and encourage attorneys to come forward with complaints. This includes serious work on training, policies and complaint resolutions efforts. While specific suggestions are beyond the scope of this article, there are many ways to find these suggestions. Two sources are listed in the endnote.[xxiv]

Where Do We Go From Here?

The discussion above highlights some of the difficulties of, and potential solutions for, eliminating harassment in the law. While beyond the scope of this article, any serious discussion surrounding eliminating bias and harassment must also include a discussion of whether ethical rules should address harassment and bullying. Many states have adopted some version of Rule of Professional Conduct 8.4, addressing the ethics of discriminatory behavior. Idaho recently went through a process of assessing this, but after the Bar (on a divided vote) concluded that the rule should be adopted, the Idaho Supreme Court (on a divided vote) declined to implement the rule and directed more study on the issue.[xxv] Firms and entities can internally deal with harassment within their walls, but some protected class harassment is perpetrated by attorneys outside our firm/organization. The only effective way to combat such offensive behavior, and provide accountability, maybe through ethical rules.

In addition, efforts to promote professionalism in the practice of law may also be an effective deterrent to harassment, as many studies have found that bullying and disrespect provides a breeding ground for unlawful harassment.[xxvi] It may be time to more closely examine, and enhance, our professionalism efforts to specifically address this issue.

Bobbi K. Dominick has practiced in the harassment and human resources areas for over three decades. Her current practice at Gjording Fouser includes working with employers on prevention systems, training, complaint investigations, and serving as an expert witness on harassment prevention response systems.

[i] See, e.g., Deborah L. Rhode, From Platitudes to Priorities: Diversity and Gender Equity in Law Firms, 24 Georgetown Journal of Legal Ethics 1041 (2011); Douglas E. Brayley & Eric S. Nguyen, Good Business: A Market-Based Argument for Law Firm Diversity, 34 J. Legal Prof. 1, 4-8 (2009); Jason P. Nance & Paul E. Madsen, An Empirical Analysis of Diversity in the Legal Profession, 47 Connecticut Law Review 271 (2014).

[ii] Stefanie K. Johnson, What 11 CEOs Have Learned About Championing Diversity, Harvard Business Review (August 29, 2017) located at https://hbr.org/2017/08/what-11-ceos-have-learned-about-championing-diversity.

[iii] Id.

[iv] Stephanie Ann Scharf, The Problem of Sexual Harassment in the Legal Profession and its Consequences (February 2018) located at https://www.scharfbanks.com/sites/default/files/assets/docs/report.pdf.

[v] Jessica R. Gunder, Women in Law: A Statistical Review of the Status of Women Attorneys in Idaho, The Advocate, (February 2019).

[vi] Alison M. Nelson, Spotlight on Bias, The Advocate (February 2019).

[vii] See, e.g., Achieving Long-Term Careers for Women in Law, report pending, ABA Commission on Women in the Profession, located at https://www.americanbar.org/groups/diversity/women/initiatives_awards/long-term-careers-for-women/.

[viii] See ABA Disability Statistics Report, 2011, ABA Commission on Mental and Physical Disability Law, https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/uncategorized/2011/20110314_aba_disability_statistics_report.pdf.

[ix] https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat11.htm.

[x] U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, Select Task Force on the Study of Harassment in the Workplace, EEOC (June 2016) located at https://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/task_force/harassment/report.cfm (EEOC Report).

[xi] EEOC Report, at pp. 13-14.

[xii] Chang and Chopra, “Where are All the Women Lawyers?” https://www.360advocacy.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/ChangChopraArticle-1.pdf.

[xiii] The Florida Bar, 2015 YLD Survey on Women in the Legal Profession, https://www-media.floridabar.org/uploads/2017/04/results-of-2015-survey.pdf.

[xiv] Women Lawyers of Utah, The Utah Report: The Initiative on the Advancement and Retention of Women in Law Firms (Oct. 2010), at http://utahwomenlawyers.org/wp-content/uploads/wlu_report_final.pdf.

[xv] EEOC Report, p. 8.

[xvi] EEOC, 1990 Policy Guidance on Current Issues of Sexual Harassment, https://www.eeoc.gov/policy/docs/currentissues.html.

[xvii] Lilia M. Cortina, et. al., Researching Rudeness: The Past, Present, and Future of the Science of Incivility, 22 Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 299 (2017); Sandy Lim & Lilia M. Cortina, Interpersonal Mistreatment in the Workplace: The Interface and Impact of General Incivility and Sexual Harassment, 90 Journal of Applied Psychology 483 (2005).

[xviii] Chelsea R. Willness, et. al, A Meta-Analysis of the Antecedents and Consequences of Workplace Sexual Harassment, 60 Personnel Psychology 127 (2007).

[xix] A good collection of the types of behaviors identified as problematic is included in the Florida Bar’s 2016 Survey on Gender Equality in the Legal Profession, located at https://www-media.floridabar.org/uploads/2017/04/2016-Survey-on-Gender-Equality-in-the-Legal-Profession.pdf

[xx] See, e.g., Heather McLaughlin, Who’s Harassed, and How? Harvard Business Review (January 31, 2018) located at https://hbr.org/2018/01/whos-harassed-and-how; Audrey Carlsen, et. al, #MeToo Brought Down 201 Powerful Men. Nearly Half of Their Replacements are Women, New York Times (October 29, 2018) located at https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/10/23/us/metoo-replacements.html.

[xxi] EEOC Report, pp. 25-28.

[xxii] Mindy Bergman, et al., The (Un)Reasonableness of Reporting: Antecedents and Consequences of Reporting Sexual Harassment, 87(2) J. Applied Psychology 230 (2002).

[xxiii] Some studies have been done in the past, but the author could not locate any recent studies or surveys. In the current #MeToo climate, such a study would be useful in developing solutions.

[xxiv] Bobbi K. Dominick, Preventing Harassment in a #MeToo World, SHRM Publishing (2018)(detailing specific actions to take in all areas of prevention); ABA Commission on Women in the Profession, Zero Tolerance: Best Practices for Combating Sex-Based Harassment inthe Legal Profession (2018),and ToolKit located athttps://www.americanbar.org/groups/diversity/women/initiatives_awards/the-zero-tolerance-program-toolkit/zero_tolerance/; see also EEOC Report noted above.

[xxv] Chief Justice Roger Burdick, Letter to Diane Minnich, Executive Director, ISB, dated September 6, 2018.

[xxvi] Zero Tolerance, pp. 28-30. See also note xviii above for additional resources.

An Inclusive Interpretation of the Constitution

By McKay Cunningham

Lawyers and non-lawyers alike revere the Constitution as a document that embodies the nation’s greatest values. It has been called America’s civic religion. In times of political discord, the Constitution unifies those with opposing views because all agree that the Constitution is the proper legal authority. The disagreement is not whether the Constitution should apply, but how it should be interpreted.

Open-ended phrases in the Constitution like the promise of “equal protection” and “due process” have allowed recognition of several civil liberties not expressly included in the document. The Ninth Amendment recognizes that rights not listed in the Constitution are not necessarily denied: “The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.”[i]

But how does the Court identify non-enumerated rights, and how does the Court determine who is protected and who is not?

In large part, it is a question of interpretation. If the Constitution is interpreted as a static document that only reflects the intent of those who drafted it, then the document rejects values of equality, liberty, and inclusion. If the Constitution is interpreted as a “living document” that reflects the values identified in the Preamble, including liberty, democratic governance, justice, and the promotion of general welfare, the Constitution is truly an egalitarian document.

The original Constitution

The Constitution, from the perspective of those who wrote it, failed to embrace or advance diversity. It centralized power in the dominant demographic of the time, white men. Only white men could meaningfully participate in the three branches of government because voting was reserved for white men alone. And voting, in a representational democracy, is the currency of power.

Not only did the framers reserve power for themselves, they expressly denied it for others. Several provisions in the original Constitution institutionalized the nation’s greatest tragedy. Article I, §9 prevented Congress from stopping the importation of slaves until 1808. Article V barred that same provision from being altered by constitutional amendment. And Article IV, §2 – the Fugitive Slave Clause – required the return of escaped slaves, specifically invalidating laws in free states that would have protected them.

It is tempting to lay the blame for slavery at the feet of the southern states, whose economy depended on slave labor and who would not have ratified a Constitution without express protections for slavery. But many of the most influential drafters at the Constitutional Convention were slave owners, including George Washington, John Rutledge, and James Madison – the last of whom is regularly identified as the “Father of the Constitution.”

The framers’ intent

Two-hundred and thirty years ago, when only white men could vote, there were no automobiles, web sites, cell phones – or any phones for that matter. Religious practice was primarily Protestant and more homogeneous than religious practices in America today. Back then, for example, Catholics endured virile anti-Catholic bias. In the late 18th Century, nothing protected homosexuals from state-supported discrimination. Women could not vote, or work in several professions, or own property in many instances.

Interpreting the Constitution by relying on the intent of those who drafted it has resulted in exclusion and oppression of people of color, women, atheists, homosexuals, and a raft of other “non-traditional” communities. The framers, for all their wisdom, were flawed – as is every generation – and a formalistic devotion to “framer intent” when interpreting the Constitution damns society to repeat those flaws.

Framers’ intent applied to race

Nevertheless, many politicians and jurists have interpreted the Constitution by relying on the framers’ intent and the society of 1780’s America. This construct, this devotion to the framers’ intent when interpreting the Constitution, has been embraced by the Supreme Court at times throughout our constitutional jurisprudence.

1. Framers’ intent applied to race before the 14th Amendment.

In Prigg v. Pennsylvania, the Court upheld the Fugitive Slave Clause: “[W]e have not the slightest hesitation in holding that, under and in virtue of the Constitution, the owner of a slave is clothed with entire authority, in every state in the Union, to seize and recapture his slave.”[ii]

Fifteen years later, in Dred Scott v. Sandford, a former slave petitioned for freedom after his owner died in a free state. The Court denied Scott’s plea, relying on the framers’ original intent. The Court said that those imported as slaves “were not intended to be included under the word ‘citizens’ in the Constitution . . . . On the contrary, they were at that time considered as a subordinate and inferior class of beings . . . .”[iii]

2. Framers’ intent applied to race after the 14th Amendment.

The Civil War and the ratification of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments ended slavery and expanded the right to vote despite “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”[iv] The 14th Amendment targeted states that had racially discriminatory laws, promising “the equal protection of the laws” to all persons. “Equal protection” is an ambiguous phrase and could be understood to include a wide variety of people within its scope. But time and again, the Court confronted that ambiguity by adhering to the framers’ intent. To understand what the framers had in mind, the Court often inspected the context and culture of the nation at the time the language was drafted.

In 1868, when the 14th Amendment was ratified, society was racially segregated in the north and the south. Every southern state had enacted laws separating the races in virtually every aspect of life, from schools to bathrooms, to water fountains. When state segregation laws were challenged as violating the Equal Protection Clause, the Court initially upheld racial segregation and pointed to the framers of the 14th Amendment as justification for doing so. According to the Court in Plessy v. Ferguson, “Equal Protection” only meant that states cannot draft laws that intentionally harm racial minorities.[v] Requiring racial separation, by contrast, was fine because that was the norm in 1868, when the framers wrote the 14th Amendment.

Framers’ intent today

At least five current Supreme Court Justices interpret the Constitution by looking to the framers’ intent. The late Justice Antonin Scalia, for example, said that the 14th Amendment and the Equal Protection Clause do not protect women: “Certainly the Constitution does not require discrimination on the basis of sex. The only issue is whether it prohibits it. It doesn’t. Nobody ever thought that that’s what it meant.”[vi]

Justice Thomas also relies on the framers’ intent when interpreting the Constitution. In a 1995 decision, Thomas wrote that when interpreting the Constitution, “we must be guided by their original meaning, for the Constitution is a written instrument. As such its meaning does not alter. That which it meant when adopted, it means now.”[vii]

Justices Thomas and Scalia are likely correct when they assert that the framers intended no protections for women when the Constitution was adopted nor when the 14th Amendment was adopted. Four years after the 14th Amendment was adopted, the Court upheld a law barring women from becoming lawyers.[viii] Two years after that, the Court upheld a state law that allowed only men to vote.[ix] Even after WWII, the Court continued to allow gender discrimination based largely on the notion that the Constitution must be interpreted through the eyes of the framers. In a 1948 decision, the Court upheld a law that prevented women from bartending unless the woman was the wife or daughter of a male who owned the bar.[x]

If the Equal Protection Clause must be interpreted through an 1868 lens, as Justices Thomas and Scalia posit, then Equal Protection means nothing for women, homosexuals, children born out of wedlock, non-citizens or anyone other than people of color.

Framers’ intent and inequality

Reading the Constitution as a static document, as a snapshot of value judgments popular in 1789 (Constitution), 1791 (Bill of Rights), or 1868 (14th Amendment), entrenches inequities. It is not surprising that no woman has been elected president and only four have served on the Supreme Court, all of whom were appointed after 1980. It is not surprising that over 95 percent of executive positions at Fortune 500 companies are still held by men and that women’s wages are typically 75 percent of men’s wages.

And it is not surprising that one in three African American children are born into poverty, that much less is spent on the average African American’s elementary and secondary schooling than on the average white child’s, and that at every age, African Americans have a higher mortality rate than whites.

Other Interpretations

The Supreme Court does not always rely on the framers when interpreting the Constitution. Some of the most revered Supreme Court cases are those that extend fundamental rights and civil liberties beyond what they were in 1789 or 1868. In Brown v. Board of Education, the Court rejected the rationale relied upon in Plessy v. Ferguson and invalidated racial segregation in public schools.[xi]

In Loving v. Virginia, the Supreme Court struck Virginia’s law criminalizing interracial marriage. It did so, despite the framers’ intent. Laws barring interracial marriage were common in 1868. Indeed, Virginia argued as much, positing that “the Equal Protection Clause, as illuminated by the statements of the Framers, is only that state penal laws containing an interracial element as part of the definition of the offense must apply equally . . . .”[xii] The Court could strike anti-miscegenation laws as unconstitutional only by ignoring the Framers’ intent.

Likewise, no protections existed in the late eighteenth century for consensual homosexual activity. Nevertheless, the Court recognized such constitutional protections in Lawrence v. Texas.[xiii] In a series of cases, the Court has extended constitutional protection for gay marriage, even though such protections would have been foreign to the framers.

An inclusive interpretation

If the Constitution is not interpreted by the framers’ intent, how should it be interpreted? Jurists often gravitate to a theory grounded in the framers’ intent because it is understandable. Several canons of interpretation require lawyers to divine legislative intent when interpreting statutes. Doesn’t it make sense to do the same with the Constitution? Moreover, if originalism and the framers’ intent should not drive constitutional interpretation, what should?

When determining whether to recognize a new fundamental right stemming from the open-ended Due Process Clause, originalists aver that fundamental rights are limited to those liberties explicitly stated in the text or clearly intended by the framers. Others ask whether the claimed fundamental right is deeply entrenched in the history and tradition of the nation. There are many varieties of constitutional interpretation, all with benefits and detriments.

At a minimum, however, the Constitution should not be a static snapshot of the 1780s. It should be a “living” document that accounts for the inevitability of societal and cultural evolution. All of nature reflects the inevitability of change; our governing document should do so as well. But what values guide a flexible interpretation? One of the most overlooked provisions in the Constitution provides insight, the Preamble:

We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.[xiv]

The first three words denote the genesis of power in the people, not the local, state, or federal government, and they illustrate that the government serves the people, not the other way around. The core values that follow include democratic government, effective government, justice, and liberty. The exhortation to “form a more perfect Union” recognizes the need to change and the capacity to acknowledge protections for marginalized persons who have not been historically protected. The call to ensure justice and protect liberty articulates the basic values of the Constitution and should be the interpretational touchstones embraced by those charged with its interpretation. While Americans value tradition and origin, we are not constrained by them. Our governing and most revered legal document should reflect the same.

Professor McKay Cunningham joined Concordia in 2014. His scholarly research focuses on cybersecurity and data privacy, constitutional law, and property law, including voting rights, international privacy regulation, and domestic easement law. His scholarship has been featured in the Buffalo Law Review, University of Cincinnati Law Review, George Washington International Law Review, and Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law.

Professor Cunningham’s non-academic legal experience includes four years as a staff attorney at the Texas Supreme Court, four years as a litigator in Dallas, Texas, and one year as a law clerk to Judge Joel F. Dubina on the Eleventh Circuit Federal Court of Appeals. Professor Cunningham is licensed to practice law in Texas and Idaho and is a member of the Richard C. Fields Inn of Court. He has consulted for large companies and recently testified before the Idaho Senate regarding the propriety of a constitutional convention. Professor Cunningham has taught Property, Evidence, Constitutional Law among other courses, and was named Professor of the Year in 2015-16.

[i] U.S. Const. amend. IX.

[ii] Prigg v. Pennsylvania, 41 U.S. (16 Pet.) 539, 540–541 (1842).

[iii] Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393, 404–405 (1857) (emphases added).

[iv] U.S. Const. amend XV.

[v] Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896).

[vi] The Originalist, California Lawyer, January 2011, https://ww2.callawyer.com/clstory.cfm?eid=913358.

[vii] McIntyre v. Ohio Elections Commission, 514 U.S. 334, 359 (1995) (Thomas, J., concurring in the judgment).

[viii] Bradwell v. The State, 83 U.S. 130 (1872).

[ix] Minor v. Happersett 88 U.S. (21 Wall.) 162 (1874).

[x] Goesaert v. Cleary, 335 U.S. 464 (1948).

[xi] Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

[xii] Loving vs. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1, 7–8 (1967).

[xiii] Lawrence v. Texas 539 U.S. 558 (2003).

[xiv] U.S. Const. pmbl.

Avoiding Gatekeeper Bias in Hiring Decisions

By Brenda M. Bauges and Tenielle Fordyce-Ruff

Bias in hiring used to be overt. For instance, during her keynote address at the Idaho Women Lawyers 2019 Gala, the Honorable Mary M. Schroeder, Senior Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, shared her experiences trying to find a job after moving to Phoenix, Arizona, in the 1960s. She suffered through several meetings where she was told that the firm wouldn’t hire a female attorney. Then, after a meeting with a male partner who was willing to hire her, she was once again told that she didn’t have a job because another partner refused to work with a woman attorney.

While these types of incidents hopefully don’t happen today, diverse candidates can still face implicit bias in the hiring process. To help you avoid this type of bias, we will first explain why a lack of diversity hurts workplaces, what gatekeeper bias in the hiring process is, and the law governing employment in Idaho. We then offer some suggested ways to help any employer avoid gatekeeper bias.

The Benefits of Diversity in the Workplace

Increasing diversity is a smart business decision.[i] Having employees with different personalities, at various stages of their careers, as well as the more common markers of diversity like gender, race, ethnicity, cultural background, and sexual orientation improves workplace performance.[ii] Studies as far back as 2006 have heralded the benefits of diversity in the workplace.[iii] In the specific context of gender diversity, noted benefits include more collaborative leadership styles that benefit boardroom dynamics, increasing mentorship and coaching of employees and economic outperformance of competitors. More recent articles continue to tout the benefits of the diversity of all types.

For instance, working with diverse people makes everyone smarter because it challenges the brain to overcome stale thinking by focusing more on facts and processing facts more carefully; this, in turn, leads to more innovation.[iv] In addition to driving innovation, diversity at a workplace makes recruiting easier, avoids high turnover among employees, and increases employee productivity.[v] Finally, diversity in the workplace can open the employer to a deeper talent pool and to a wider market.[vi]

What is Gatekeeper Bias?

When we think of bias, we often think of discrimination. This bias or prejudice involves “dislike, hostility, or unjust behavior deriving from preconceived and unfounded opinions.”[vii] We also tend to link bias with negative emotions.[viii] Some forms of bias, however, come from positive feelings, such as in-group favoritism.[ix] In other words, some forms of bias come from positive feelings toward an individual that result in “significant discriminatory results from differential helping or favoring.”[x] Additionally, while some bias is overt and conscious, oftentimes bias is the result of implicitly held beliefs of which a person is completely unaware.

In the context of employment decisions, gatekeeper bias happens when an employment decision is based on the decision maker’s perceived preferences of the existing employers or co-workers with whom the new employee would be working.[xi] Gatekeeper bias—allowing the perceived bias of co-workers to influence employment decisions—happens even when the gatekeeper herself believes in the importance of diversity.[xii] In fact, gatekeepers may not even be aware that these considerations are factoring into the hiring, or other employment, decision. It is not uncommon for such decisions to be considered simply a commentary on who best “fits” the company culture or mission. In other words, even a commitment to diversity doesn’t necessarily prevent employers from accommodating biases in hiring decisions.

This gatekeeping bias happens because employers face a challenge with each hire: they must match unknown applicants to well-known, experience-based requirements.[xiii] Thus, each new hire represents a risk to the employer, and the persons charged with hiring decisions often allow emotions, including the desire to avoid risk and reproduce the current situation with a new employee, to creep in.[xiv] This isn’t always bad, but these emotions can mean certain candidates are excluded from consideration based on a gatekeeper’s perception that existing employees have a bias, though that might not be the word used, against the candidate’s social characteristics, which could include race, gender, or ethnicity.[xv]

Idaho and Federal Employment Law

Gatekeeper bias is especially concerning not only because diversity in the workplace makes good business sense, but also because it could open up employers to legal liability.

The Idaho Human Rights Act prohibits discrimination in employment based on race, color, religion, sex, national origin, disability, and age.[xvi] Employment decisions that cannot be based on these protected classes include hiring, termination, compensation, promotions and discipline, and other conditions or privileges of employment.[xvii] The Idaho Human Rights Act applies to employers with five or more employees for each working day in each of 20 or more calendar weeks in the current or preceding calendar year, a person who as a contractor or subcontractor is furnishing material or performing work for the state, any agency of or any governmental entity within the state, and any agent of such employer.[xviii] In addition to the Idaho Human Rights Act, some local governments have enacted legislation seeking to extend employment anti-discrimination protections explicitly on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity/expression.[xix]

Like the Idaho Human Rights Act, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits discrimination in employment based on race, color, religion, sex, and national origin.[xx] Title VII similarly covers decisions regarding hiring, termination, compensation, promotions and discipline, and other terms and conditions of employment.[xxi] Covered employers include those “affecting commerce” with 15 or more employees for each working day in each of 20 or more calendar weeks in the current or preceding calendar year, any agent of such employer, and various federal governmental entities.[xxii] In addition to the Civil Rights Act, a patchwork of other federal laws prohibit discrimination based on various characteristics in the employment context including on the basis of a disability, age, genetic information, and others.[xxiii]

Tips to Avoid Gatekeeper Bias

We have extolled the virtues of diversity in the workplace; uncovered for you the, sometimes subconscious and unintentional, role of gatekeeper bias as an obstacle to achieving such diversity; and illustrated how this phenomenon can open up employers to legal issues in light of prevailing anti-discrimination laws. The question remains, especially if gatekeeper bias is sometimes subconscious and unintentional, how does your or your client’s organization prevent gatekeeper bias from happening? Here is some guidance and some suggestions on how to prevent gatekeeper bias.

First, be aware of your implicit biases.[xxiv] We all have them. Unfortunately, too often we do not want to admit, to ourselves or others, that we categorize people based on their appearances, history, or yes, specific culture-conforming attributes. We do not want to admit that we feel more comfortable with people who act, look, and think like us. It is time to get over that. Until we do, we will never win the battle against implicit bias. Have your hiring managers take implicit bias tests or training.[xxv]

Second, create definable rubrics for your hiring process.[xxvi] Systemizing your hiring process will go a long way towards ensuring your hiring process results in the most qualified, successful candidate. For example, keep your job description handy and only ask questions related to job-related duties. Consider asking the same questions to all candidates. Assign numbers for candidate answers with “1” being unable/incompetent to complete the required task and “10” being perfectly able/competent to complete the required task.

Third, be very careful of assigning too much weight to “likability,” “fit,” or “gut feeling.” These feelings could just be implicit biases in disguise. Consider, instead, including another element to your hiring rubric for personal interaction or ability to work well in a team setting, if those are truly important components of the job at issue. Then make sure you rate the candidates based on the definite qualities in the rubric.

Finally, diversify your hiring panel. Have multiple employees in your office responsible for giving input on job candidates. You can have the candidates meet one-on-one with multiple employees, or in a group setting. Regardless of the format, ensure that the hiring panel includes different genders, cultures, and ages. Diversifying your panel does not mean that every member will have an equal say in who gets hired, but it does ensure that the feedback that goes into the decision is varied and more likely to be free from individual bias. This diversifying can also go a long way toward ensuring that a single person’s feelings about how a candidate’s co-workers would feel about him are based on explicit ratings or reactions, not biased assumptions.

Brenda M. Bauges is an Assistant Professor and Director of Externships and Pro Bono Programs at Concordia University, School of Law. She currently serves on the board of directors for Idaho Women Lawyers, is the co-chair of the Fourth District Pro Bono Committee, and is a member of Attorneys for Civic Education and the Idaho Legal History Society. She and her family are avid whitewater rafters and spend most of their summers enjoying Idaho’s wild and scenic rivers.

Tenielle Fordyce-Ruff is an Associate Professor of Law and the Director of the Legal Research & Writing Program at Concordia University School of Law. She also serves as the editor for Carolina Academic Press’ state-specific legal research series. You can access all of her Advocate articles at https://works.bepress.com/tenielle-fordyce-ruff/.

[i] David Rock & Heidi Grant, Why Diverse Teams are Smarter, Harvard Business Review, available at https://hbr.org/2016/11/why-diverse-teams-are-smarter (last visited April 9, 2019).

[ii] Rose Johnson, What Are the Advantages of a Diverse Workforce? Houston Chronical (Jan. 28, 2019), available at https://smallbusiness.chron.com/advantages-diverse-workforce-18780.html (last visited April 9, 2019) ; see also What Are the Benefits of Diversity in the Workplace? available at https://theundercoverrecruiter.com/benefits-diversity-workplace/ (last visited April 9, 2019).

[iii] Alexandra S. Grande, Caitlin Kling, & Brenda M. Bauges, Women on State Boards and Commissions: Is Idaho Where it Wants to Be?, The Advocate, Volume 59, No. 3/4, p. 30 (March/April 2016).

[iv] David Rock & Heidi Grant, Why Diverse Teams are Smarter, Harvard Business Review, available at https://hbr.org/2016/11/why-diverse-teams-are-smarter (last visited April 9, 2019).

[v] Sylvia Ann Hewlett, Melinda Marshall & Laura Sherbin, How Diversity Can Drive Innovation, Harvard Business Review (Dec. 2013) available at https://hbr.org/2013/12/how-diversity-can-drive-innovation (last visited April 9, 2019); Kim Abreu, The Myriad Benefits of Diversity in the Workforce, available at https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/240550 (last visited April 9, 2019); Rose Johnson, What Are the Advantages of a Diverse Workforce? Houston Chronical (Jan. 28, 2019), available at https://smallbusiness.chron.com/advantages-diverse-workforce-18780.html (last visited April 9, 2019.

[vi] Kim Abreu, The Myriad Benefits of Diversity in the Workforce, available at https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/240550 (last visited April 9, 2019).

[vii] Anthony G. Greenwalk & T homas F. Pettigrew, With Malice Toward None and Charity for Some: Ingroup Favoritism Enables Discrimination, American Psychologist 669 (October 2014).

[viii] Id. at 670.

[ix] Id.

[x] Id. at 672.

[xi] Bill Hathaway, Three Is Not Good Company for Women Job Seekers, Yale News (October 19, 2018), available at https://news.yale.edu/2018/10/19/three-not-good-company-women-job-seekers?utm_source=YNemail&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=yn-10-22-18 (last visited March 22, 2019).

[xii] See id. (noting that the gender biases of potential co-workers can influence hiring decisions even when the gatekeeper is committed to gender diversity).

[xiii] Emotionalizing Organizations and Organizing Emotions, 86 (Barbara Sieben ed., 2010).

[xiv] Id. at 87, 100.

[xv] Id. at 100.

[xvi] Idaho Code §§ 67-5909.

[xvii] Id.

[xviii] Idaho Code § 67-5902(6).

[xix] See e.g. Boise City Ordinance Title 5, Chapter 15, available at https://www.sterlingcodifiers.com/codebook/index.php?book_id=1079(last visited April 9, 2019).

[xx] 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2.

[xxi] Id.

[xxii] 42 U.S.C. § 2000e(b); 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16.

[xxiii] See e.g. Americans with Disabilities Act, 42 U.S.C. § 12101 et seq.; Americans with Disabilities Act Amendments Act; Rehabilitation Act, 29 U.S.C. § 791 et seq.; Age Discrimination in Employment Act, 29 U.S.C. §§ 621 et seq.; Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act, 42 U.S.C. § 2000ff et seq.; Uniformed Services Employment and Reemployment Rights Act, 38 U.S.C. § 4311.

[xxiv] See Rebecca Knight, 7 Practical Ways to Reduce Bias in Your Hiring Process, Society for Human Resource Management (April 19, 2018), available at https://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/hr-topics/talent-acquisition/pages/7-practical-ways-to-reduce-bias-in-your-hiring-process.aspx (last visited March 29, 2019).

[xxv] Project Implicit, https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/takeatest.html (last visited March 29, 2019).

[xxvi] See Rebecca Knight, 7 Practical Ways to Reduce Bias in Your Hiring Process, Society for Human Resource Management (April 19, 2018), available at https://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/hr-topics/talent-acquisition/pages/7-practical-ways-to-reduce-bias-in-your-hiring-process.aspx (last visited March 29, 2019).

A Modern Civil Rights Movement: What Lawyers Need to Know About LGBTQ Families

By Mary E. Shea

Family Law Forever Changed

In the summer of 2015, we watched celebrations nationwide when the United States Supreme Court fundamentally changed the American legal landscape by holding that the Fourteenth Amendment mandates equal legal marriage rights for same-sex couples.[i] This watershed ruling means that all 50 states must allow legal marriage for same-sex couples and all 50 states must recognize legal same-sex marriages that have been solemnized elsewhere.

Although this decision was celebrated widely as settling the question once and for all, by the time this opinion was issued on June 30, 2015, most states, including Idaho, had already reached the same conclusion legislatively, or by binding federal court decision.[ii] What we have learned in the last few years is that granting same-sex couples the legal right to marry did not really create much controversy in applying marriage and divorce laws state by state. This article will provide a brief overview of the family law issues the legal system is grappling with in the wake of Obergerfell.

Constitutional Protections for Alternative Families

Courts throughout the country are still sorting out whether to treat same-sex or transgendered persons as part of a quasi-suspect class so that discriminatory laws should be subject to heightened scrutiny, similar to gender.[iii] To survive, laws that discriminate against a quasi-suspect class must be substantially related to an important government interest. Discriminatory laws can survive intermediate scrutiny if they have a very good reason to exist.[iv]

One federal court has held recently that sexual identity should be considered a true suspect class similar to race. [v] This means laws based on sexual identity would have to survive strict scrutiny. Applying strict scrutiny to these laws would likely be fatal because such laws rarely survive strict scrutiny.

In Obergerfell and the related family law cases, the Court so far has focused on the important and fundamental nature of the rights denied, rather than on the legal status of the people who have been denied the rights. That analysis, in the marriage context, has been enough.[vi] State laws restricting the right have been struck down consistently, such that even felons facing lifetime imprisonment must be given the right to marry.[vii]

Parenting Rights Have Become More Complex

However settled marital rights are, parenting rights are a different story. Same-sex couples, today, cannot have what the law has indelicately but traditionally referred to as “natural” children except through the use of Assisted Reproductive Technology (“ART”). They can adopt children in all 50 states if they are married, and in most states even if they are not married, although that has only been true in very recent history.[viii]

Idaho adoption laws have never prevented adoption based on sexual preference or marriage and Idaho statutes have never required termination of a natural or legal parent’s rights in order to complete an adoption. Although never prevented, there was no Idaho case holding such until 2014.[ix] If a same-sex couple wishes to have children, only one of the spouses will be biologically related to the child, or neither of the partners will be biologically related to the child.[x] Courts and legislatures throughout the country, including here in Idaho, in light of the obligation to recognize same-sex marriage on the same legal terms as heterosexual marriage, are still working through how to redefine legal parenthood as a result of that biological reality.

The United States Supreme Court has clarified same-sex parenting rights in two important cases post-Obergerfell, both decided per curium without oral argument. In the first case, a lesbian couple together for 16 years conceived three children through ART, with one of the partners serving as the biological mother. With the full knowledge and consent of the biological mother, the same-sex partner adopted all three children and they were raised together as a family. The family moved to Alabama and subsequently, the partners split up. The Supreme Court unanimously reversed Alabama’s attempt to relitigate the legitimacy of the Georgia adoption.[xi]

In Pavan v. Smith, two same-sex married couples who conceived using artificial insemination sued Arkansas, because Arkansas would permit only the birth mother to place her name on the birth certificate. The Arkansas statutes, applying the marriage presumption, permitted husbands of birth mothers to be placed on birth certificates for children conceived the same way. The United States Supreme Court held that this constituted unlawful discrimination against same-sex couples, stating that “the Constitution entitles same-sex couples to civil marriage on the same terms and conditions as opposite-sex couples.”[xii]

Post-Obergerfell, state courts deciding this issue have all agreed that the gendered marital presumption has to be applied in a non-gendered way, and they have so far given legal parenting rights and responsibilities to non-biological married same-sex parents. In a recent Hawaii case, the non-biological parent was not permitted to rebut the legal parenting presumption in order to avoid paying child support. The Hawaii court reasoned that if the Uniform Parenting Act is applied in a gender-neutral way, a legally presumed heterosexual parent who is later determined not to be the biological parent could still be made to pay child support, which applies equally to a same-sex partner as the intended parent of the child. [xiii] The Idaho case on this issue is also interesting because in that case the lesbian couple never married. The evidence was uncontroverted, however, that they would have been married when their child was born in 2012 if legal marriage had been available to them in Idaho at that time.[xiv]

Married Same-Sex Couples Who Divorce May Not Opt Out of Parental Obligations

Two of these cases, the Mississippi and the Arizona cases, also raise an interesting estoppel argument to prevent a biological mother from “revoking” her consent to consider her partner the legal parent of the child they conceived and raised together. Equitable estoppel is a legal principle known well to the family law courts; it has been applied successfully in Idaho on several occasions to prevent parents from “changing their minds” about who the legal parent should be.[xv] It has a logical place in this context. A parenting relationship should not be severed simply because a biologically related parent no longer wants the company of their ex-partner. If parents have allowed the parental bond with a child to form in a legal way, they should not be able to retract that relationship simply and only because they have the genetic advantage.

There is a case on appeal in Idaho, where a Magistrate Court denied legal parenting rights to a married same-sex parent for a child conceived and born during the marriage. The trial court held that the marital presumption was rebutted by the non-biological relationship. This will be an important case for Idaho practitioners to watch.

Unmarried Families Should Perfect Their Parenting Rights

The LGBTQ families in the most peril concerning parental rights are the co-parents who never marry and never adopt. In 2016, the Idaho Supreme Court refused to allow an unmarried, same-sex co-parent to assert any legal parenting rights because there is no procedural vehicle for her to assert them in Idaho. The biological mother did not sign a Voluntary Acknowledgment of Paternity at birth, which could have created a legal parenting presumption even without marriage.[xvi] The parents were advised incorrectly (based on pre-2014 assumptions) that as a same-sex couple, the non-biologically related mother could not adopt.

Idaho recognizes an “equitable parenting” rule, whereby a person who has had a “parent-like” relationship with a child can gain legal parent-like rights, such as custody or visitation.[xvii] In this same-sex parenting case, the Idaho Supreme Court clarified the equitable parent rule to be a substantive rule, not a procedural rule: it does not give a parent a vehicle into court. Unless a putative parent has standing to get into court through a legal process involving child custody rights such as divorce, or guardianship, they cannot assert Stockwell equitable parenting rights.[xviii]

Unmarried co-parents in Idaho who are not biologically related to the child they are parenting should be advised to seek adoption because Idaho does not give them any path currently to legal parenthood in the event the co-parents split up and the “natural” parent no longer wishes to have them around.

Alternative Reproductive Technologies Raise Additional Legal Issues

Currently, Idaho regulates only Artificial Insemination (“AI”). There are no statutes concerning surrogacy agreements, although there is a Supreme Court Administrative Order that assigns all such cases to one Judge, ostensibly to assure consistent application of the law to facts. The Uniform Law Commission has updated its Uniform Parentage Act to consider recent developments in the law.[xix] But, Idaho’s AI statute is based on a 1982 version of the Uniform Parentage Act and has not been updated.[xx] The purpose seems to be to help determine legal parentage despite the biology concerns.

On its face, it discriminates between married and non-married parents, and it requires a physician’s assistance for a procedure that does not require medical intervention. Most problematically, Idaho law does not account for the many other, more modern ways ART can now be used to create a life for partners outside of true genetic relationships, such as egg and embryo donation, whereby a birth mother may not even be genetically related to the infant she delivers. The AI statute was at issue in the 2016 same-sex equitable parenting case discussed above, Doe v. Doe, but the legal challenge was not addressed when the Idaho Supreme Court held the plaintiff lacked standing to assert any rights.

Conclusion

Although it took several decades to accomplish, once same-sex marriage equality reached the tipping point, change came very rapidly. Parenting was a very important part of the same-sex marriage decisions and debate. Ultimately, the courts concluded that same-sex parents are no more or less able to raise children well than traditional heterosexual partnerships. As the Sixth Circuit held, “Gay couples, no less than straight couples, are capable of raising children and providing stable families for them. The quality of such relationships and the capacity to raise children within them turns not on sexual orientation, but on individual choices and individual commitment.”[xxi] Parenting rights for the LGBTQ community is the next family law frontier. Practitioners would be well served to keep up with this rapidly evolving area of the law.

Mary E. Shea is a partner at Merrill and Merrill, where she has a general civil practice with an emphasis on family law. Mary is a certified child advocate and member of the NACC. Before coming to Idaho, Mary was a civil rights litigator with the Virginia Attorney General’s Office, and prior to that, she was a law clerk for the Virginia Supreme Court. Mary received her law degree from the University of Richmond, and her BA from the College of William and Mary. In her spare time, Mary enjoys hiking and skiing throughout Idaho and the Rocky Mountain West and spending time with her kids and dogs.

[i] Obergerfell v. Hodges, 576 U.S. , 135 S.Ct. 2584 (2015).

[ii] Latta v. Otter, 19 F. Supp. 3d 1054, 1086-1087 (D. Idaho 2014), aff’d, 771 F.3d 456 (9th Cir. 2014), cert. denied, 135 S.Ct. 293 (2015) (permitting same sex marriage in Idaho since October 10, 2014).

[iii] In F.V. v. Baron, 286 F. Supp.3d 1131 (D. Idaho 2018), Idaho was required to permit gender changes for adults on birth certificates without showing such birth certificates as “amended.” Idaho did not appeal, and Idaho has been permitting these changes on birth certificates since April 2018. Following 9th Circuit case law, transgender status was treated as a “quasi suspect” class. This quasi suspect class analysis was also applied in the Idaho same sex marriage case, Latta v. Otter, footnote 2 supra. The Supreme Court has recently granted certiorari in an employment law case that may settle the question of whether LBGQT belong to a protected class.

[iv] E.g., Rostker v. Goldberg, 453 U.S. 57 (1981), which upheld the male-only draft rules. The “legitimate reason” for discrimination was that women were not eligible for combat duty in the military. Times have changed significantly, such that a federal judge recently has found the male only draft rules are discriminatory, because women are now eligible for combat positions. National Coalition for Men, et al. v. Selective Service System, et al., Case No. 4:16-cv-03362, Doc. 87, USDC SD Tex, Houston Div., Filed February 22, 2019.

[v] Karnoski v. Trump, Case No. 2:17-cv-01297-MJP, Doc. 233, USDC WD Wash, Seattle, Filed April 13, 2018 (granting summary judgment against administration’s policies towards transgendered military).

[vi] Justice Roberts’ dissent in the watershed decision striking down Section 3 of the Defense of Marriage Act (“DOMA”) specifically criticized the vagueness of the majority opinion’s analysis, authored by Justice Kennedy. The Second Circuit had applied intermediate scrutiny to the federal law which on its face discriminated against even legally married same sex partners. The Supreme Court did no more than mention the Second Circuit’s treatment of the issue, without offering any opinion at all as to whether it was correct or incorrect. United States v. Windsor, 570 U.S. 744 (2013). Justice Kennedy also wrote the Obergerfell decision two years later, and he again offered no clarification of whether sexual orientation should be treated as a quasi-suspect or suspect class.

[vii] Turner v. Safley, 482 U.S. 78, 95 (1987).

[viii]On March 31, 2016, a federal court struck down Mississippi’s ban on same sex adoption – the very last state to hold out. https://southernequality.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Judge-Jordan-III-opinion-in-Campaign-for-Southern-Equality-v.-Mississippi-Department-of-Human-Services-et-al.pdf. In VL v. EL, 136 S.Ct. 1017, 194 L.Ed.2d 29 (2016) (per curium), without hearing oral argument, SCOTUS unanimously overturned the Alabama Supreme Court’s decision which had refused to recognize a same sex adoption issued out of the Georgia courts. The Court held that the Full Faith and Credit Clause demands that all states recognize adoptions from other states, and that lack of jurisdiction is the only basis for rejecting an out of state adoption.

[ix] Idaho Code § 16-1501 et. seq; In Re: Adoption of Doe, 156 Idaho 345, 326 P.3d 347 (2014).

[x] There are some cutting edge ART technologies that may one day permit same sex couples to have genetically related children, but these are still very experimental, and there a lot of bio ethics questions to address. See, e.g.:

https://jme.bmj.com/content/44/12/835;

[xi] V.L. v. E.L., 136 S.Ct. 1017, 194 L.Ed.2d 29 (2016) (per curium)

[xii] Pavan v. Smith, 137 S.Ct. 2075 (2017).

[xiii] LC v. MG and Child Support Enforcement, WL 4804417, Hawaii Supreme Court October 4, 2018; Strickland v. Day, 239 S.3d 486 (Miss. 2018); McGlaughlin v. Jones, 401 P.3d 492 (Ariz. 2017); Ayala v. Armstrong, 2018 WL 3636524, Case 1:16-cv-00501-BLW Document 59 Filed 07/30/2018 (D. Idaho).Roe v. Patton, 2:15-cv-00253-DB, Doc. 15, USDC D. Utah, Central Div., Filed July 22, 2015.

[xiv] Ayala v. Armstrong, 2018 WL 3636524, Case 1:16-cv-00501-BLW Document 59 Filed 07/30/2018 (D. Idaho).

[xv] Gordon v. Hedrick, 159 Idaho 605, 364 P.3d 951 (2015)(mother not permitted to withdraw her signature on a VAP absent clear and convincing evidence of fraud, duress, or material mistake of fact); Doe v. Roe, 142 Idaho 202, 127 P.3d 105 (2005) (Father learned during divorce he was not the natural father of the child; biological dad was not permitted to rebut the legal marital presumption because he asserted his rights too late); Miller v. Miller, 96 Idaho 10, 523 P.2d 321 (1974) (Mother could not revisit divorce action to rebut husband’s legal paternity).

[xvi] Idaho Code § 7-1119 et seq. It should be noted that there has not yet been a case in Idaho holding that unmarried same sex partners may use a VAP to establish presumptive legal parenting rights.

[xvii] Stockwell v. Stockwell, 116 Idaho 297, 775 P.2d 611 (1989).

[xviii] Doe v. Doe, 162 Idaho 254, 395 P.3d 1287 (2017)

[xix] https://www.uniformlaws.org/committees/community-home?CommunityKey=c4f37d2d-4d20-4be0-8256-22dd73af068f

[xx] I.C. § 39-5401 et. seq.

[xxi] DeBoer v. Snyder, 772 F.3d 388 (6th Cir. 2014), rev’d, Obergerfell v. Hodges, 135 S.Ct. 2584 (2015).

The Mansfield Rule and the Idaho State Bar: Let’s Do This!

By Anna E. Eberlin

What does diversity look like here? It depends on how you define “here” – is it a particular firm or partnership? Is it our local legal market? All attorneys in the state of Idaho? Attorneys in the West? Or even on a national level? For me, a female real estate, construction, and finance transactional attorney in Boise, Idaho, diversity is viewed through each of those lenses. I have personally witnessed the progress we have made over the past 13 years, since starting out as a junior associate with no context for diversity except growing up in Eastern Idaho – which is not exactly a place teeming with diversity – to today, where the conversation about diversity is front and center, as it should be.

In my experience, the membership of the Idaho State Bar (ISB) is (slowly) becoming more diverse. And the numbers seem to support this, at least as far as gender: in 2009, 75% of the members of the ISB were men, with 25% women, and in 2018, the numbers had changed to 72% and 28%, respectively.[i] Still, we clearly have a long way to go. This article will present an emerging approach to increasing diversity within law offices, share the results of early efforts, and provide an outlook for future efforts to improve diversity across the spectrum of the legal profession.

Enter the Mansfield Rule

Diversity, in theory, has much support across many platforms. But diversity in practice? That’s the problem. The Diversity Lab, an incubator for innovative ideas and solutions that increase diversity and inclusion in the legal industry, has set out to change this.[ii] The “Mansfield Rule” was one of the winning ideas from the 2016 Women in Law Hackathon, which is an annual event created by the Diversity Lab in conjunction with Bloomberg Law and Stanford Law School. The genesis of the Mansfield Rule is the National Football League’s (NFL) Rooney Rule.

The Rooney Rule, named after Dan Rooney, who was once head of the NFL’s diversity committee and owner of the Pittsburgh Steelers, requires NFL franchises to interview at least one racially diverse candidate for all top-level positions in the NFL, including head coaching jobs, general manager jobs, and other equivalent positions. In the years following the implementation of the Rooney Rule, the number of minorities hired to fill head-coach positions doubled.[iii]

The Mansfield Rule is named after the first woman to be admitted to practice law in the United States, Arabella Mansfield, who took the Iowa bar exam in 1869. Ms. Mansfield impressed the bar examiners so much that they stated that her brilliant performance defied the idea that ladies cannot practice law.[iv] Now, 150 years later, diversity in the lawyer ranks is still woefully inadequate. Thus, the Diversity Lab developed this idea to increase diversity in the law profession by designating tangible thresholds and goals, namely, to promote more women and minorities into leadership roles within their firms or companies.

One of the Rooney Rule Success Stories

Mike Tomlin, an African American championed by Dan Rooney under the Rooney Rule, became the Head Coach of the Pittsburgh Steelers, leading the team to a Super Bowl Championship, and multiple division and conference championships.

Early Adopters, Early Results!

In 2017, a total of 44 law firms across the United States first adopted the Mansfield Rule as part of a pilot program under the Diversity Lab’s supervision. The Mansfield Rule requires participating firms to consider 30% of women and racially diverse attorneys for 70% or more of the firms’ openings in leadership positions – including firm-wide leadership positions, various committees, practice group leaders, or office leaders – during a yearlong review period. If the firm met the threshold, then it is qualified as “Mansfield Certified.”

After the first year in the pilot program, 41 firms have been Mansfield Certified.[v] My firm, Holland & Hart LLP, is one of them. As one of the smallest firms to participate, Holland & Hart enthusiastically took on the implementation of the Mansfield Rule. As a result, it became “Mansfield Certified Plus.” The “Plus” status indicates that in addition to meeting the pipeline requirements during the process of filling leadership positions, it also successfully reached at least 30% women and minority lawyer representation in a notable number of current leadership roles and committees.

The Diversity Forum found measurable results across the 41 firms that achieved Mansfield Certification. Before adopting the Mansfield Rule, only 20% of the participating firms tracked the diversity of candidates considered for partnership, for lateral senior positions, and for leadership and governance roles; as Mansfield Certified firms, all 41 of the firms now track this. After the adoption of the Mansfield Rule, 95% of firms have increased formal discussions among firm leaders regarding diversity in candidate pools for leadership positions and lateral hiring. In addition, many firms have added reporting requirements internally regarding Mansfield Rule statistics.[vi] These results are supported by research that finds that law firms with women in leadership roles have more women lawyers overall and 5% more women equity partners on average.[vii]

Expansion of the Rule

Running from July 2018 to July 2019, Mansfield 2.0 was implemented last year, which expanded the rule to include LGBTQ+ attorneys as well as women and minorities.[viii] For example, if firm management has identified a short list of five candidates for an opening on the executive committee, the Mansfield Rule requires that two of the candidates would need to be women, minorities, or LGBTQ+. In addition, Mansfield 2.0 will measure consideration for roles in client pitch meetings and measure transparency in appointment and election processes to all lawyers in their firms. The Diversity Lab will continue to measure and report data on the progress of participating firms.

My experience with the Mansfield Rule has been both eye-opening and incredible. As a “reward” for achieving Mansfield Certification and Certification Plus, firms were invited to send their newly promoted diverse and women partners to Client Forums held around the country last year. As a newly promoted partner in 2018, I was invited to go to the San Francisco forum to learn from, connect with, and pitch to in-house legal teams from national and international companies across multiple industries and practice areas.

At the Client Forum in San Francisco, it was clear that in-house legal teams are committed to diversity just as much as law firms are and are 100% committed to moving the needle on diversity throughout the entire legal industry. Some in-house counsel went so far as to say that if the outside legal teams performing the company’s work did not include at least one diverse team member, then the firm would no longer be doing the work for that company. Companies wanted to see diverse pitch teams – and not just for facetime during the pitch, but for performing the work as well.

The legal industry is last to the party:

Facebook implemented its own version of the Rooney Rule to increase diversity in tech.

House Democrats have adopted the Rooney Rule to push diversity in staff.

Amazon adopted the Rooney Rule to increase board diversity.

The NCAA adopted the College Rooney Rule.

Diversity is an Ongoing Commitment

I have strived to bring back to my office and my overall firm the teamwork, camaraderie, and excitement that I experienced at the Client Forum. Increasing diversity is not lip service at Holland & Hart – especially in my real estate world but notably, the firm as a whole. Holland & Hart’s management committee recently approved an updated Diversity & Inclusion Plan that includes diversity goals modeled on the Mansfield Rule, such as:

- Consideration of diverse attorneys for at least 30% of the candidate pool for recruitment for open attorney positions, including partner and non-partner lateral, entry level, and summer clerk positions.