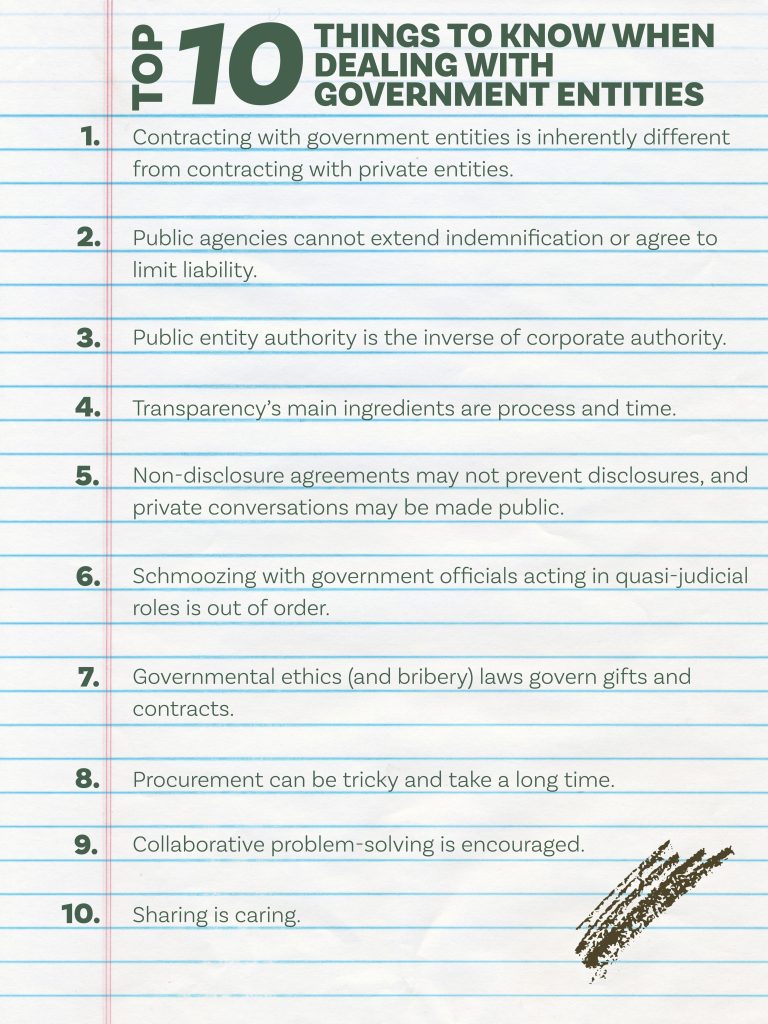

Top 10 Things to Know When Dealing with Government Entities

Alexandra A. Breshears

Emily D. Kane

With special thanks to Julie Weaver for the top 10 article concept and her considerable contribution.

Compliance with laws that govern public agencies may present practical complexities and timelines that occasionally take private practitioners by surprise. This article includes, in no particular order, a list of the top ten things to know, and some pro tips to use, when dealing with government entities.

1. Contracting with government entities is inherently different from contracting with private entities.

Negotiating contracts with government entities requires awareness of statutory and constitutional restrictions and directives that differ from those typically encountered in the private sector. Contract terms impacted include those relating to appropriations, assignment, governing law, jurisdiction, arbitration, and waiver of jury trial.

State entities are subject to appropriations and spending authority granted by the Idaho Legislature, while action by local entities requires budgetary approval and signature by their elected officials (or staff designees). For state entities, the Idaho Constitution prohibits any expenditures in excess of legislative appropriations.[i] State agencies and officers are prohibited from entering into contracts that create any expense or liability in excess of an appropriation[ii] and any such contract is void.[iii] Additionally, the general legal requirements for payments by Idaho agencies are set by statute.[iv]

For State entities, contracts cannot be assigned without written approval by the Administrator and the Idaho Board of Examiners.[v] A contract assigned in violation of this provision can be annulled, and the Idaho Controller is prohibited from paying the assignee.[vi]

Negotiating jurisdictional provisions in contracts with State agencies is also subject to unique constraints. As a sovereign state, the State of Idaho and its governmental entities are not subject to the jurisdiction of the courts of its sister states, and the Idaho Legislature has not consented to the waiver of this limitation by state agencies. The 11th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution provides limitations on the jurisdiction of federal courts over claims against the State of Idaho.

State agencies have restrictions on waiving a jury trial, and any term of a contract subjecting a party to arbitration conducted outside the State of Idaho is void.[vii]

Governmental entities cannot contractually waive their statutory and constitutional mandates, and attempts to do so are voidable, if not void as a matter of law. Local agencies generally follow these principles in negotiating contracts as well – though usually pursuant to policy in order to minimize any risk to public funds, rather than pursuant to a specific statutory mandate.

PRO TIP #1: Be aware of specialized statutory and constitutional requirements when negotiating contracts with government entities.

2. Public agencies cannot extend indemnification or agree to limit liability.

Private entities are accustomed to mutual indemnification provisions in agreements; however, in the governmental context, indemnification is viewed as an obligation of funds that have not been appropriated in the current or a future budget year. As such, the Idaho Constitution and Idaho Code place limits on the ability of a State entity to indemnify another party.[viii] Similar restrictions exist for local entities.[ix]

For an entity serving the public interest of Idahoans, a request to limit the liability of a contractor is considered to be a matter of public policy. Limitations of liability are authorized only when it is appropriate for the taxpayers of Idaho to bear the risk of the contractor’s breach, or where the limitation is in excess of any reasonable contractor liability under the contract.

Insurance is another key difference when dealing with governmental entities. State entities participate in the internal State-retained risk program, which is not “insurance” under the statutory definitions.[x] Thus, a private entity may not be added as an “additional insured,” subrogation may not be waived, and policy limits and requirements may differ.

Private entities should consider, however, that even though a government entity may not indemnify another party, the State of Idaho has waived its sovereign immunity for torts as described in the Idaho Tort Claims Act and for contract claims arising from a properly entered contract.[xi] Given the available remedies, the need for indemnification, limitations of liability, or heightened insurance requirements is greatly mitigated.

PRO TIP #2: Public sector attorneys cannot agree to the private sector’s boilerplate indemnity and insurance provisions, but comparable protections are available under the Idaho Tort Claims Act.

3. Public entity authority is the inverse of corporate authority.

Public entities and corporate entities enjoy inverse inherent authorities. State agencies in Idaho have no inherent authority.[xii] In general, state agencies have no authority outside of what the Idaho Legislature “specifically grants to them.”[xiii] Thus, every action of a state entity must be supported by a specific statute. A similar rule applies to local entities: cities and counties may make and enforce ordinances only to the extent that such ordinances do not conflict with Idaho Code.[xiv]

By contrast, corporate entities are permitted to take whatever actions are not specifically prohibited by statute or the corporate bylaws. When government entities and corporate entities interact, the opposing levels of authority can cause confusion and resistance to the numerous limits placed upon a governmental entity’s authority to act.

PRO TIP #3: Work with the public entity’s counsel early in a project or agreement to ensure that the entity is authorized to take the contemplated actions.

4. Transparency’s main ingredients are process and time.

Government agencies’ decision-making is subject to statutory timelines designed to maximize transparency and public participation – though not agility. Under Idaho’s open meeting laws, the governing board of a public agency is required to provide at least five days’ notice of a meeting, and to publish the agenda at least 48 hours in advance.[xv]

For the benefit of the board as well as the public, several days before the statutory 48-hour window for agenda notice, agencies typically publicly distribute all of the contracts, memoranda, and other materials that will be presented and discussed. Logistically, this means that the clerk preparing the meeting packet must have the final documents in hand at least two weeks before the meeting. Specific statutes require additional process and noticing, often weeks in advance.[xvi] Though private lawyers may be able to negotiate edits and changes in direction until moments before their clients make the final decision, noticing obligations compel government lawyers to plan ahead and finalize documents long before their clients take up the matter.

PRO TIP #4: Build in a few extra weeks to your timeline where a government agency is the decision-maker.

5. Non-disclosure agreements may not prevent disclosure, and private conversations may be made public.

Private businesses routinely enter into non-disclosure agreements, but the Idaho Public Records Act (“IPRA”)[xvii] makes this challenging, if not impossible, for public agencies. IPRA’s general rule is that any “information relating to the conduct or administration of the public’s business” is a public record,[xviii] of which anyone can have a copy upon request.[xix]

There are numerous enumerated exceptions to this rule; for example, IPRA does allow agencies to protect from disclosure of “trade secrets,” as that term is defined by Idaho Code § 74-107(1). But IPRA does not protect the existence of a contract or the agency’s expenditure of funds. This means that settlement agreements, information shared in the context of economic development inquiries, and draft contracts may be subject to disclosure. Even verbal conversations with elected officials must be disclosed, if the topic is a matter to be considered by the agency’s board.[xx]

PRO TIP #5: Presume that any information you provide to a government employee or official must be publicly disclosed.

6. Schmoozing with government officials acting in quasi-judicial roles is out of order.

In reviewing an application or hearing an appeal, government boards sit in a quasi-judicial capacity,[xxi] which means that members are legally bound to avoid ex parte communications.[xxii] As with a court hearing, the right to due process entitles applicants and appellants to a decision confined to the record before the decision-maker. In the context of a decision made by a government board, the public also has a constitutional right to meaningful participation in a public hearing.[xxiii] This means that off-the-record conversations about pending or upcoming decisions – whether they occur via email, in the grocery store aisle, or over lunch – are improper, because the public is not privy to that exchange. Where such conversations do happen, board members must disclose – on the record – the fact and nature of the discussion.[xxiv] Practices that are routine in private business: giving decision-makers a preview of a proposal, asking for feedback on conceptual plans, requesting ideas to make a proposal more attractive, are problematic in the context of government board decisions.

PRO TIP #6: Communicate with elected officials regarding pending or upcoming matters only at duly noticed meetings.

7. Governmental ethics (and bribery) laws govern gifts and contracts.

Public officials, including employees, attorneys, elected officials, and even volunteer commissioners,[xxv] are subject to specific ethics laws that protect the integrity of both public funds and agency actions.[xxvi] For example:

- Public officials cannot accept gifts of $50 or more in value,[xxvii] or of any value where the recipient’s jobincludes making decisions (e.g., awarding contracts, issuing permits, regulatory sign-offs) related to the giver.[xxviii]

- While private companies are free to contract with anyone in their network, including family members, in the public sector, agencies and their employees are not. It is unlawful for a government employee or a family member to have a private interest in a contract to which the agency is a party.[xxix]

- Public officials who are separately involved in private business are also subject to rules regarding actions taken in their public capacity that would yield a “private pecuniary benefit” to the official or a family member.[xxx]

Agency employees are responsible for adherence to the governmental ethics rules and consequences of a violation, but private practitioners must understand that compliance with governmental ethics laws can take additional time or may even completely bar a transaction, depending on the relationships of the individuals involved.

PRO TIP #7: Use words of affirmation instead of gifts to show appreciation for your public sector colleagues.[xxxi] And when dealing with governmental employees or officials wearing both public and private hats, be aware that governmental ethics laws may have practical effects on the private company’s dealings with that government agency.

8. Procurement can be tricky and take a long time.

State entities are subject to the requirements of the State Procurement Act[xxxii] unless specifically exempted. [xxxiii] The nuances and complexities of the State Procurement Act are outside of the scope of this article; however, suffice it to say that there are many requirements relating to competitive bidding, required contract terms, and bid challenges. There are various types of solicitations, each with their own requirements, as well as general government contracting requirements.[xxxiv] Special industries, including public works, possess additional requirements. There also exist numerous local procurement laws, which are similar to state procurement laws.[xxxv]

PRO TIP #8: When advising a company that is responding to a request for proposals, read the solicitation instructions carefully and be aware of specific laws that may impact your client. If a proposal is not responsive and compliant with law, the government entity may have to disqualify the bid.

9. Collaborative problem-solving is encouraged.

Public sector attorneys typically do not bill their clients by the hour, but like most lawyers, their calendars are full and their time is scarce. This combination of factors means that government lawyers generally welcome the opportunity to work together to solve a problem, rather than proceeding directly to cross purposes.

The best approach will differ with each issue, but whether it’s a molehill or a mountain, it’s almost always worth having a conversation before filing a complaint. Even if the process must ultimately become adversarial, an early attempt to collaborate will open the lines of communication and may be fruitful in addressing preliminary and peripheral issues.

PRO TIP #9: Consider, as a first step in resolving a client’s issue with a government agency, contacting the agency attorney to brainswarm ideas for a constructive path forward.[xxxvi]

10. Sharing is caring.

In Idaho, public sector law offices have a long-standing tradition of collegiality. It is typical for government attorneys to reach out to each another and seek suggestions for solving a problem or share prior experience that might benefit a fellow agency. We freely share templates, experience, and subject-matter knowledge.

This generosity reflects the general civility of the Idaho public sector bar and it extends to our private sector counterparts. Private attorneys presented with a substantive legal question about a government matter, from land use to procurement to water law, should feel free to cold-call a government lawyer and ask how things work. For the most part, we are happy to share our knowledge, or a referral to someone with more information. Not only is this a professional courtesy and a duty of all lawyers,[xxxvii] it is inherent in the public sector culture. Public service includes accountability to both the public at large, and to our fellow attorneys.

PRO TIP #10: Reach out to your friendly neighborhood public sector lawyer. We’re from the government, and we’re here to help![xxxviii]

Alexandra A. Breshears currently works as a Deputy Attorney General for the State of Idaho in the Division of State General Counsel and Fair Hearings and serves as the 2022-2023 Chair for the Government and Public Sector Lawyers Section. Prior to that, she clerked for Idaho Supreme Court Justices Jim Jones and Robyn Brody. The writing expresses the views of the author alone and not the views of the Office of the Attorney General.

Emily D. Kane, a graduate of the Northwestern School of Law at Lewis & Clark College, practices municipal law as a deputy city attorney with the City of Meridian. She served as a prosecutor with the City of Boise and a Deputy Attorney General in the Natural Resources Division of the Idaho Attorney General’s Office before joining the Meridian City Attorney’s Office.

[i] Idaho Const., Art. VII, § 11; Art. VIII, § 3.

[ii] Idaho Code § 59-1015.

[iii] Idaho Code § 59-1016.

[iv] Idaho Code §67-2302.

[v] Idaho Code §67-9230.

[vi] Idaho Code § 67-1027.

[vii] Idaho Code §29-110.

[viii] See Idaho Const. art VII, § 11; Idaho Code § 59-1015; Idaho Code § 59-1016.

[ix] Idaho Const., art. VIII, § 3.

[x] Idaho Code §§ 67-5773–76.

[xi] Idaho Code Title 6, Chapter 9 (waiving sovereign immunity for tort claims under the Tort Claims Act); Grant Const. Co. v. Burns, 92 Idaho 408, 413, 443 P.2d 1005, 1010 (1968) (waiving sovereign immunity for properly entered contracts).

[xii] In re Idaho Workers Compensation Board, 167 Idaho 13, 20, 467 P.3d 377, 384 (2020) (citing Idaho Power Co. v. Idaho Pub. Utils. Comm’n, 102 Idaho 744, 750, 639 P.2d 442, 448 (1981)); see also Richard Henry Seamon, Idaho Administrative Law: A Primer for Students and Practitioners, 51 Idaho L. Rev. 421, 439 (2015).

[xiii] In re Idaho Workers Compensation Board, 167 Idaho at 20, 467 P.3d at 384 (citing Idaho Retired Firefighters Assoc. v. Pub. Emp. Ret. Bd., 165 Idaho 193, 196, 443 P.3d 207, 210 (2019)).

[xiv] Caesar v. State, 101 Idaho 158, 159, 610 P.2d 517, 518 (1980).

[xv] Idaho Code § 74-204(1).

[xvi] See, e.g., Idaho Code § 67-6509 (noticing requirements of Local Land Use Planning Act); Idaho Code § 63-1311A (noticing requirements for adoption of fees); Idaho Code § 50-1402 (noticing requirements for a city’s disposition of real property).

[xvii] Idaho Code §§ 74-101 et seq.

[xviii] Idaho Code § 74-101(13).

[xix] Idaho Code § 74-102(1).

[xx] Idaho Historic Preservation Council v. City Council of Boise, 134 Idaho 651, 656, 8 P.3d 646, 651 (2000).

[xxi] Cooper v. Board of County Commissioners of Ada County, 101 Idaho 407, 410, 614 P.2d 947, 950 (1980).

[xxii] 134 Idaho at 654.

[xxiii] Gay v. County Commissioners of Bonneville County, 103 Idaho 626, 629, 651 P.2d 560, 563 (Ct. App. 1982).

[xxiv] 134 Idaho at 656.

[xxv] Idaho Code § 74-405 (authorizing noncompensated commissioners to “cleanse” a conflict of interest if the transaction is competitively bid and the commissioner submits a low bid).

[xxvi] Idaho Code § 74-402.

[xxvii] Idaho Code §§ 18-1356(5)(c), 18-1359(1)(b).

[xxviii] Idaho Code § 18-1359(1)(b).

[xxix] Idaho Code § 18-1359(1)(d). (There are limited exceptions to this rule where there are less than three (3) suppliers of a good or service within a 15-mile radius (Idaho Code § 18-1361) and for part-time public servants (Idaho Code § 18-1359(7)).)

[xxx] Idaho Code §§ 74-404 (prohibiting public employees from taking any action or making a formal recommendation concerning a matter in which they have an undisclosed conflict of interest); 74-403(4).

[xxxi] See Gary Chapman, The Five Love Languages: How to Express Heartfelt Commitment to Your Mate (1992).

[xxxii] Title 67, chapter 92, Idaho Code.

[xxxiii] See also IDAPA 38.05.01.

[xxxiv] See Title 18, chapter 87, Idaho Code and title 29, chapter 1, Idaho Code.

[xxxv] Title 67, chapter 28, Idaho Code.

[xxxvi] Tony McCaffrey, Brainswarming: Because Brainstorming Doesn’t Work, Harvard Business Review (2014); https://hbr.org/2014/06/brainswarming-because-brainstorming-doesnt-work

[xxxvii] Idaho Rule of Professional Conduct 6.1(b)(3) (lawyers’ responsibility to improve the law, legal system, and legal profession).

[xxxviii] Paraphrasing President Ronald Reagan’s August 12, 1986 declaration of “the nine most terrifying words in the English language.”