The Idaho State Bar 100th Anniversary: The Early Days by Hon. Michael J. Oths

The Idaho State Bar is celebrating its 100th anniversary in 2025. This article recounts the development of the Bar through the end of the 1930s and is drawn from minutes and transcripts of the annual meetings. It is also part of a larger project to document the history of the Bar.

The notion of lawyers gathering to share knowledge and fellowship long predates our country. In medieval England, Roman Catholic clergy customarily taught law. In 1218, Pope Honorius III decreed that Roman civil law should take precedence and prohibited clergy from teaching English common law. In response, King Henry III prohibited the teaching of civil law. This schism between the Church and the Crown led to the formation of Inns of Court, geared to common law. Those Inns, combining both social and academic elements, survive, in some form, to our current time.

Until the late 19th Century, bar associations as we know them did not exist in this country. Nevertheless, informal collections of lawyers were a vital part of the practice of law, especially in frontier areas. In Illinois, for example, Abraham Lincoln and his colleagues “rode the circuit” for months at a time, resolving lawsuits by day and conducting post-mortem in the tavern by night (Lincoln, by the way, was a teetotaler).[1]

The American Bar Association was formed in 1876, in Saratoga Springs, New York. Its stated purpose was:

“The advancement of the science of jurisprudence, the promotion of the administration of justice and a uniformity of legislation throughout the country….”

The first lawyers to practice in the Idaho Territory were admitted in 1866.[2] In those early days, verifying a lawyer’s bona fides could be problematic, but the Court’s response to misrepresentation could be swift. One lawyer from the very early days was disbarred almost immediately. His name is crossed out in the lawyer registry and in red ink is written: “A warning to all guilty of like turpitude.”

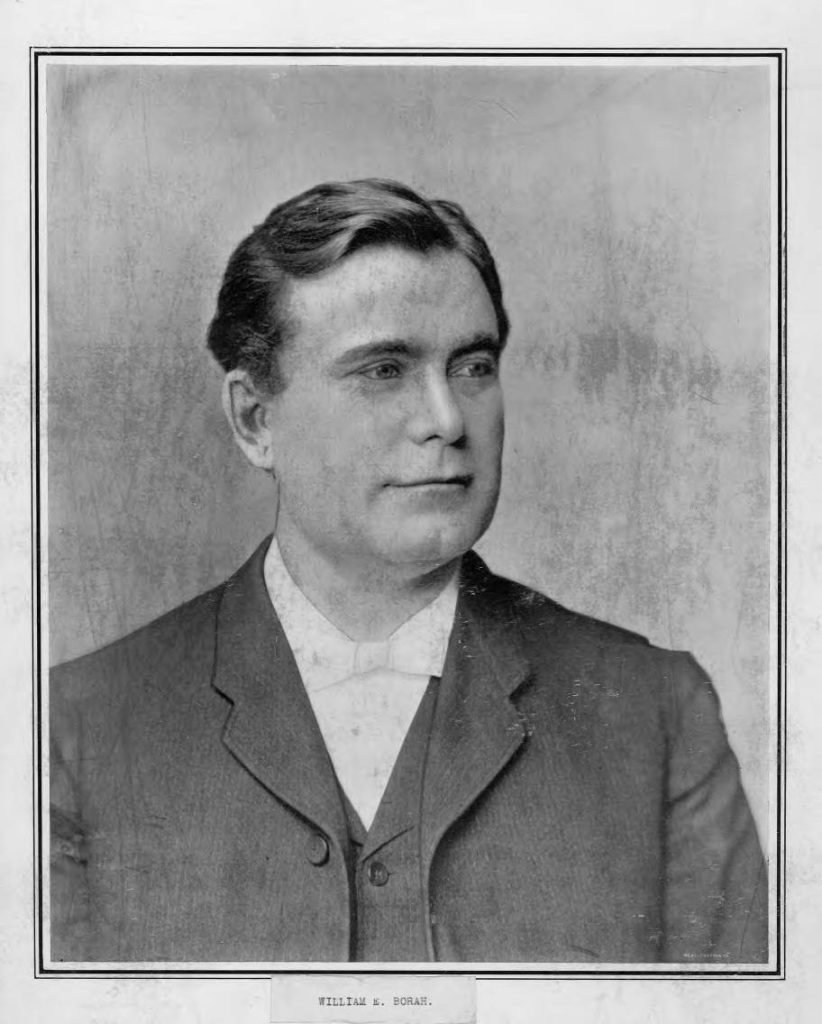

The early registry includes some noteworthy names. Future Governor of Idaho and Bar President James H. Hawley was admitted in 1871. William E. Borah (“The Lion of Idaho”) was admitted in 1891. Idaho’s first female lawyer, Helen Young, was admitted in 1895. Later, in 1911, Branch Rickey briefly practiced law in Boise, prior to attaining fame for bringing Jackie Robinson to Major League Baseball.

First Voluntary Bar

By statehood, in 1890, there is no known record of any formal organization of Idaho lawyers. The first statewide[3] bar association (“ISBA”) was formed in 1899.

While we don’t have any minutes of the 1899 meeting, there is a transcript of a speech given by the President, Richard Z. Johnson. He was one of the first Idaho lawyers, admitted in 1867.[4] The 1899 meeting was in Boise and President Johnson noted that invitations had been sent to every other county in the state and that they had received exactly zero replies. He suggested biennial meetings, due to the travel difficulties in Idaho.[5]

President Johnson noted the need for lawyers to keep up with advancing technology—specifically the telegraph. The bulk of his talk was devoted to criticism of the proposed Civil Code pending in the Legislature. He complimented the new edition of Revised Statutes, which was apparently printed in Omaha.

After the 1899 meeting, records are sketchy until after World War I, although we do have a list of the bar officers from those first 20 years. Later minutes indicate the ISB held no meetings between 1901 and 1909. It is clear the ISB was a voluntary organization with limited enthusiasm.

Early ISB Officers

During this period some noteworthy lawyers were officers of the ISBA.

Oliver O. Haga was Treasurer from 1909 to 1911. He was one of the founders of the firm now known as Eberle, Berlin, Kading, Turnbow and McKlveen.

James Hawley was President from 1917-1919 following by six years his term as Governor. He was the first of three members of his family to serve as President, preceding his son, Jess, in the 1920s and his grandson, Jack, in the 1970s.

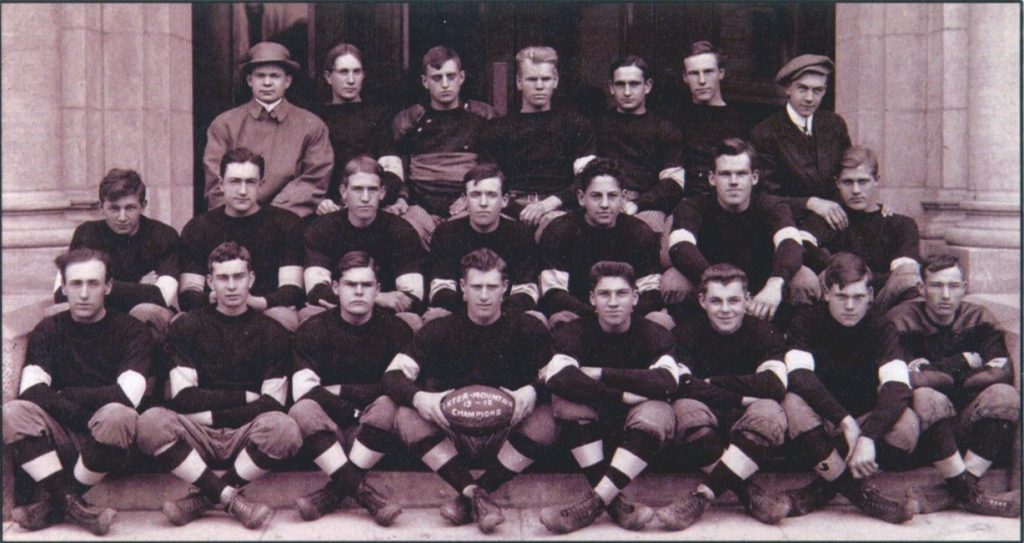

O.W. Worthwine served as Secretary during the same period. He had been a college football player for the University of Chicago, whose coach was the legendary Amos Alonzo Stagg. Worthwine had a long and colorful history in Boise, starting with his time as a coach for Boise High School. In that role he promoted a “National Championship” football game between Boise High and Wendell Phillips High School of Chicago, in 1912. He eventually entered a law partnership with the firm of Hawley, Puckett and Hawley and appears in the Idaho State Bar minutes for decades thereafter.[6] [7]

The first known minutes of the ISBA were produced in 1921. That meeting was held in January, in Boise. Dues were set at $2.00 per year. The treasury balance was $919, and the members voted to raise the Bar Secretary’s compensation by 140 percent, to $120 per year.

The roster from that 1921 meeting lists no women in attendance. The participants discussed a number of topics, including whether the Bar should implement minimum fees schedules and whether to pursue formation of a mandatory bar association.

The President, future Idaho Supreme Court Justice James Ailshie, made a lengthy address to the membership. Many of his topics probably sound familiar, like the distrust by the public of lawyers and courts and that losing parties blamed the system. He urged prosecution of unauthorized practice of law (“UPOL”) cases, advocated for the streamlining of discipline cases, and stressed the need to address delays in the court system. He also suggested that bar meetings necessarily needed to be held in Boise. As we will see, the contention over where to hold the Bar convention has ebbed and flowed over the following decades.

The meeting concluded with a speaker from Twin Falls making a speech about suggestions for improvement of the Bar, including fall meetings for better weather and to better prepare for the legislative sessions. He suggested the need for district meetings. Finally, he noted that the 1919 meeting had included all Boise lawyers, except two.

The Mandatory Bar

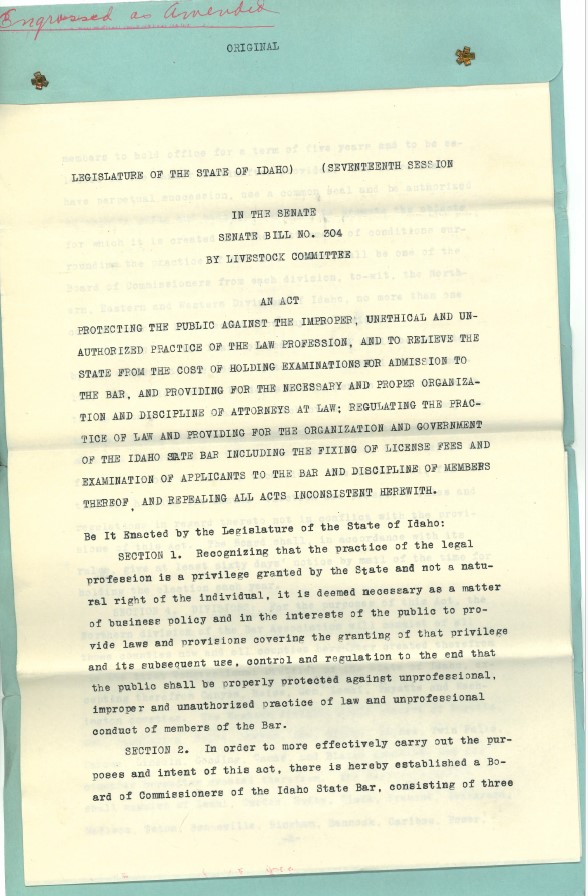

Two years later, in 1923, the Bar had finalized a proposal for the formation of a mandatory bar association. The concept of a mandatory (or integrated) bar was in its infancy. North Dakota was the first state to form an integrated bar, in 1921. Alabama and Idaho would be next, in 1923. (In the “insert-joke-here” category, the Bar organization bill was introduced through the livestock committee).

The careful reader will ask, “Why are we celebrating a one-hundred-year anniversary in 2025 if the Bar was formed in 1923?” After the January 1923 ISBA meeting, the proposed legislation creating the Bar was filed. The bill passed in that year’s Legislature, creating a Board of Commissioners and providing for annual meetings.

Unfortunately, no money was appropriated for the operation of the Bar, so nothing happened other than an organizational meeting. The intent of the bill was for Bar dues to be the source of funds, but the State Auditor refused to handle it that way, contending that the bill had not included an “appropriation” as required by the state constitution. The officers of the bar filed a writ of mandate in the Supreme Court, resulting in the case of Jackson v. Gallet.[8]

A divided Idaho Supreme Court sided with the Auditor and denied the writ of mandate. The proponents then went back to the 1925 Legislature with a new bill, which also passed. That bill apparently satisfied the concerns from Jackson v. Gallett.

First Annual Meeting

The first actual meeting of the Idaho State Bar (“ISB”) was held in September 1925, in Lewiston. Despite Judge Ailshie’s suggestion, the first five annual meetings were held throughout the state. After Lewiston in 1925, they were held the following years in Pocatello, Boise, Coeur d’Alene, and Idaho Falls respectively.

After multiple attempts to encourage attendance, the Board of Commissioners concluded that holding the meetings in “summer resort areas” might show an improvement, so the meetings were held in McCall and Hailey in the mid-1930s.

At one-point, former President Ailshie even suggested that lawyers who failed to attend a bar meeting for three straight years should be disbarred! The Bar also considered tripling bar dues to $15 but offering a $10 refund if a lawyer attended the Bar meeting.

Other efforts to increase participation included the creation of the first sections—a judicial council and a prosecutors’ section, with consideration given to creating a young lawyer section. District Bars were also created for the first time.

The spirit of inclusion apparently did not extend to female members of the Bar. In 1935, the President reminded those in attendance to tell their wives that the annual banquet was a “stag” event. Mary Smith, of Rexburg, is the first woman to appear in the transcripts, in 1937, when she made an address to the Annual Meeting about the need for reform in the Idaho pardon system. She apparently wasn’t invited to the banquet, however, a fact she noted in her address.[9]

Borah

Over the years, Senator William Edgar Borah was an active participant in the Idaho State Bar, which is something of an irony, since a recurring criticism was that he never spent time in Idaho—he only lived here from 1891 to 1906.

In 1925, the Bar had invited a speaker from San Francisco to discuss the need for a World Court. He agreed, then balked unless Senator Borah would come and debate the question. In fact, Borah did agree on short notice and came to Lewiston. Senator Borah’s objection to the World Court was tied to his complete objection to the League of Nations and anything he thought was associated with it.

In 1927, Borah addressed the Annual Meeting on the “Mexican Land Problem” which had its roots in leased oil lands. In his introductory remarks that year he noted that in the Senate cloakroom he had been touting Governor Hawley as one of the country’s most accomplished trial lawyers. He noted that one of his fellow Senators piped up that Hawley had been handicapped by his choice of co-counsel in the Steunenberg assassination trial. The co-counsel, of course, was Borah himself.

In 1934, Senator Borah’s treatise was read concerning adherence to the Constitution (which can be read as a comment on the New Deal). He also delivered an address and again expressed his opposition to the proposed World Court.

Judicial Issues

The preferred method of making judicial selections was (as it continues to be) an ongoing topic of concern. Beginning in the late 20s, the Bar began to advocate for non-partisan judicial elections and the Legislature eventually agreed in 1933. In 1928, a member of the Bar proposed that judges should be appointed by the Governor, from a supplied list—a concept that again was realized nearly a half-century later. The Legislature was far less sympathetic to suggestions that the Bar should control the process of judicial selection or that Supreme Court terms be for 10 years.

By around 1930, the Bar had created a Judicial Council, consisting of lawyers and judges, with the intent to make policy recommendations to the Legislature and Supreme Court. One suggestion was to abolish probate courts altogether (accomplished in 1970). Another was that county clerks shouldn’t be elected officials (at least as regards court duties).

Many of the Judicial Council proposals highlighted a clear division between lawyers from small towns and those from “big cities.”

In 1927, Bar Commissioner Jess Hawley noted that the governor had vetoed a judicial pay increase bill and a bill to define UPOL had failed—judicial pay had not increased since 1909. He noted: “The Legislature looks at our bills with suspicion,” in that year only four out of 100 legislators were lawyers.

Bar Admissions

Bar admissions, then as now, were a major concern. In 1923, the Bar discussed the need to make more careful study of applicants from other states, apparently in light of some unworthy applicants slipping through. Initially, the ISB permitted reciprocal admission from other states but in 1937, that was abolished, and a six-month residency requirement was enacted (reciprocal admission was reintroduced in Idaho in 2002). It is interesting to note that from 1925 through 1939 the membership of the Bar declined from 629 lawyers to 515. By 1943, that number had shrunk to 409 (current membership is around 7,400)[10]. Much to the present relief of the author, the Bar declined to pursue a 1935 proposal that would have made all lawyers over 65 be examined for continuing competence.

In 1939, the Bar held an extended discussion about whether Idaho should have diploma privilege and decided not to. That year, a speaker spoke to the topic: “Is the Bar exam too focused on minutiae?”

Familiar Names

Lawyers from the transcripts of the 20s and 30s will be familiar to current ISB members. In 1925, A.L. Merrill was elected as commissioner from Pocatello in a seven-way race. In 1928, both Carl Burke Sr. and Raymond Givens Sr. appear in the minutes. Participants in 1936 included Willis Moffatt, future U.S. Senator Herman Welker (then prosecutor from Washington County), and the newly elected Commissioner J.L. Eberle. The 1937 meeting was held in Idaho Falls. The attendees were welcomed by Chase Clark (lawyer, then-Mayor of Idaho Falls, future governor and Federal Judge, and father-in-law of Frank Church). In 1938, the newest Commissioner was Clarence Thomas (different guy). In 1939, E.B. Smith (future ISB President, Supreme Court Justice, and namesake of Quane Smith) gave an address on “should lawyers be bonded?”

University of Idaho College of Law

The Annual Meeting regularly featured addresses by the dean of the University of Idaho (“UI”) College of Law. In 1925, Dean Robert McNair Davis spoke to the convention and noted that his school was “not for the indolent and the stupid.” The next year the Bar President noted the original applicants failing the bar had passed, claiming that they had received a wakeup call to study harder. He noted: “A law school is no place to summer fallow athletes.”

In 1931, the Bar heard an address from Russ Randall (young lawyer and future Bar President). He discussed that ethics had been removed from UI College of Law curriculum. He also asked that more practical skills be taught in law school. A veteran bar member applauded Mr. Randall as a young lawyer who “know[s] that he does not know anything about the practice of law.[11]”

In 1932, the Twin Falls District Bar, acting on some misinformation about the cost, proposed elimination of the UI College of Law altogether. That drew a sharp and immediate reaction from the dean.

In 1933, the minutes contain the “Idaho Law Journal” which appears to be the forerunner of the UI Law Review.

Criminal Law

Criminal law topics were regularly discussed, often raised by the Prosecutors’ Section. In 1926, a major debate was whether the prosecution should be permitted to comment about a Defendant’s election not to testify in a criminal trial. In 1931, a speaker discussed why “plea bargains are bad.”

Also, in 1931 it was noted that crime was down statewide. There had been zero felony cases filed in 1929 in Caribou and Oneida Counties, and only one in several other counties. A comment was made that almost half of all criminal cases were “petty” prohibition cases.

In 1934, Judge Koelsch of Boise spoke on public sentiment to speed up trials and suggested it was a myth. He also discussed and opposed a proposal that prosecutors be required to disclose witness lists to Defendants (“only aids unscrupulous defendants”). He further suggested voir dire of potential jurors was a waste of time.

Other Topics

In 1935, bar discipline hearings were opened to the public.

Another topic that has resonated throughout the years is the Bar’s concern about unauthorized practice of law. In 1930, it was hoped that recent Supreme Court cases would address that, and in 1936 it was reported that the Bar had succeeded in getting some UPOL judgments versus bond companies.

Bar Leadership

One constant through the Bar’s first two decades was the guiding hand of Bar Secretary Sam Griffin—a position now called Executive Director. He served in that role from 1919 to 1951. He and recently retired Executive Director Diane Minnich comprise nearly two-thirds of service in that role in the Bar’s history.

Conclusion

The Idaho State Bar has a rich history through its century of existence. While some of the topics change, many of the concerns from the early decades are woven throughout the years. Continuing to study its origin and history will help to guide the Bar into its next century.

[The author thanks the following people for research assistance in preparation of this article: Supreme Court Clerk Melanie Gagnepain, members of the Legislative Council’s Office, Neil McFeeley, Judge Jim Cawthon and (of course) Diane Minnich].

Hon. Michael Oths is a Senior Magistrate Judge in Ada County. Prior to his appointment as a Magistrate, Oths was Bar Counsel for the Idaho State Bar for 17 years. He spent nine years as a member of the Ada County Historic Preservation Society.

[1] Willard King: “Riding the Circuit with Lincoln,” American Heritage, February (1955).

[2] The Idaho Supreme Court maintains bound books containing the signature of every lawyer admitted since that time.

[3] Italics added because the Idaho State Bar Association was mostly a Boise enterprise.

[4] David H. Leroy, From Tents to Towers to Kitchen Tables: The Evolution of the Law Office in Idaho, 67 The Advocate 32 (2024).

[5] For an illustration of the difficulty of Idaho travel during this era, see J. Anthony Lukas: Big Trouble, Simon and Schuster, 1997, pp. 340 et. seq.

[6] https://boiseguardian.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Friday-August-24-2012-21.pdf.

[7] Id.

[8] 39 Idaho 382, 228 Pac. 1068 (1924). A disciplined lawyer filed a subsequent challenge to the formation of the Bar, but his claims were rejected by our Supreme Court. In Re Edwards, 45 Idaho 676, 266 P. 667 (1928).

[9] Mary Smith was a longtime law partner of noted Idaho political power Lloyd Adams. She practiced law into the 1990’s and is the subject of an in-depth interview in the August 1988 issue of The Advocate.

[10] Idaho State Bar Membership Data (Accessed December 11, 2024).

[11] ‘Proceedings of the Idaho State Bar’ Idaho Law Journal, VII (1931), p. 260. https://isb.idaho.gov/wp-content/uploads/ISB_Vol_VII_1931_1897.pdf.