Child Representation: The Value of Being Seen, Heard, and Represented

by Jessalyn R. Hopkin and Stacy L. Pittman

In child protection cases, children are the focus. When a child suffers from neglect or abuse, the state can step in to protect the child. From shelter care, to case planning, to case closure, the court must examine the best interest of the child. Unfortunately, what is frequently overlooked in child protection cases, is the child. Though the case itself is about the child’s best interest, in many court rooms across Idaho, children do not have a voice to opine what they believe is in their best interest. The same children who are meant to be protected in cases of neglect or harm deserve to have counsel with the same duties of undivided loyalty, confidentiality, and competent representation as is due to adult clients.

A 2018 report conducted by the Idaho Office of Performance Evaluations (“OPE”) found that anywhere between 19% and 23% of children in child protection cases are unrepresented throughout the entirety of their case by either a guardian ad litem or a public defender.[1] While we have state mandates requiring representation, there remains an identifiable gap. Child representation is not only inconsistent but, arguably, insufficient due to lack of training and practice standards. Recent studies suggest that children desire and deserve a voice in all proceedings, but especially those that affect them.[2] Therefore, all children should have the right to effective, competent, and compassionate representation at all stages of a child protection case. It is not only important to the child, but also important to ensure fair process at every level and to keep families together.

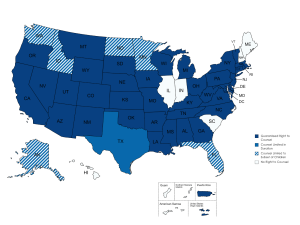

Idaho is one of only thirteen states that does not guarantee the right to counsel for children in child protection cases.[3] While there is no federal right to counsel for children during the pendency of child protection cases, most states have recognized the importance of counsel for children and have enacted state statutes. Though these statutes do not all look the same, they do encompass various models of representation guaranteeing children have a legal representative with rights and duties owed to them as the client.

In Idaho, any child who is at issue in a child protection case and under the age of 12 receives a Guardian ad Litem (“GAL”).[4] GALs are generally volunteers, often through the Court Appointed Special Advocate (“CASA”) offices which are in all seven judicial districts in Idaho. Under state statute, GALs shall be appointed counsel to represent them.[5] The GAL/CASA is a party to the case, receiving notice, the opportunity to be heard, and guaranteed representation.

If there is no GAL/CASA volunteer or program available, the court shall appoint an attorney to represent the child.[6] If the child is under 12 and has a GAL there is discretion for the court to appoint counsel for the child in “appropriate cases.”[7] The court may consider “the nature of the case, the child’s age, maturity, intellectual ability, ability to direct the activities of counsel and other factors…”[8]

Currently, there is no statewide judicial procedure for discretionary appointments; individual judges determine if children under 12 should be represented by counsel. The GAL is generally expected to convey the wishes of the child to the Court; however, there is no expectation nor obligation to request counsel for the child and/or comment on the factors the court considers for appointment. Thus, most children under the age of 12 are unrepresented by counsel and are not a party to their own case. A ten-year-old child could express disagreement with the GAL’s recommendations and have no means of presenting evidence to support his or her position. In addition, the child would be the only person in court expected to personally convey their thoughts, feelings, and preferences without an attorney standing beside them to aid and support.

Children 12 and older are appointed client-directed counsel to represent them.[9] This means that the child is the client, and the attorney owes the child the same duties as an adult client. For example, the attorney must work with the child to identify his/her legal objectives and abide by the child’s decisions concerning those objectives.[10] One of the most important aspects of child representation is counseling the child. Children may have diminished capacity, either because of their minority or trauma, and the attorney must engage in active, age-appropriate counseling to ensure a child can make informed decisions.[11]

Also, of paramount importance, counsel for the child owes a duty of confidentiality. In a child protection case, counsel is the only person with whom the child has protected confidential communications. Idaho Department of Health and Welfare caseworkers as well as GALs do not owe any fiduciary duties to the child; for example, conversations between the caseworker or GAL and child(ren) are not confidential and may very well end up in a report to the court and parties.

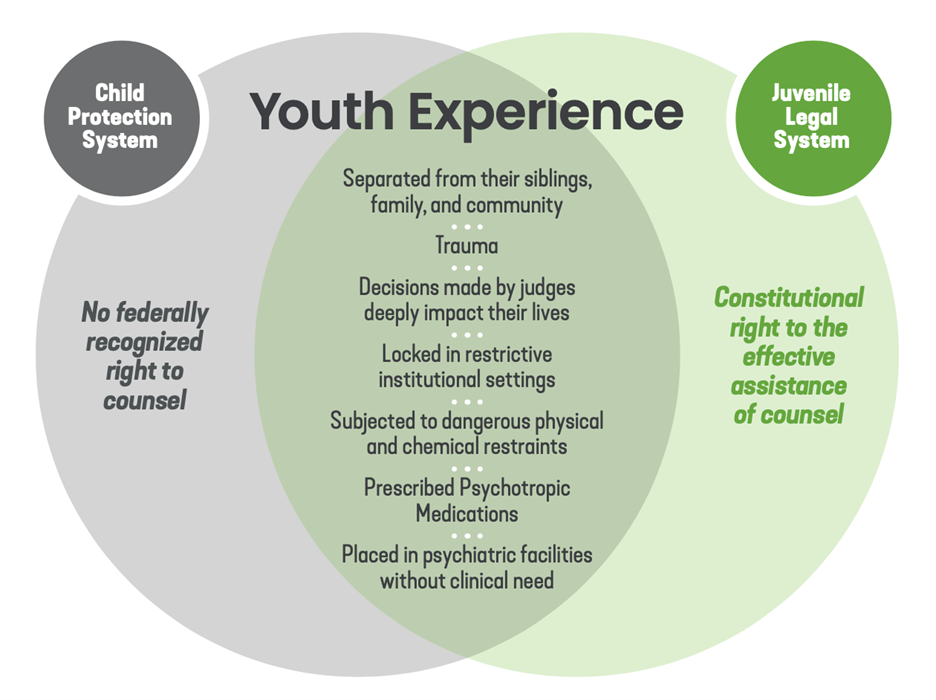

In contrast, children involved with the juvenile justice system, must be appointed an attorney if they are under 14 years of age.[12] Once the child reaches the age of 14, they can waive their right to an attorney.[13] Unlike children in child protection act cases, if someone under the age of 18 is charged with what would be a crime, an attorney is appointed to directly represent that youth. Due to Idaho also having no minimum age of criminal responsibility, some children as young as 7 are being charged with juvenile offenses and therefore represented by counsel.[14]

Children in juvenile justice and child protection cases experience similar losses and restrictions. They can each be removed from their families and communities and locked in facilities. In fact, it is not uncommon for two children to sit next to one another in a facility; one, who was placed there by way of the juvenile justice system, having been represented by counsel and being provided full due process with the other, a child removed from his home with custody vested in the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare, unrepresented, and placed in the facility by his caseworker without knowledge of the court.

Nationally, there is a shift towards guaranteeing representation of all youth and children in child protection cases by competent and well-trained attorneys. Separating children from their family and placing them in foster care is traumatic, life-altering, and potentially unsafe.[15] Foster care does not guarantee child safety and well-being. “In fact, […] the weight of social and scientific evidence suggests that children who are removed from their homes based on allegations of abuse and neglect often face more abuse and neglect in foster care. This is anathema to a system whose stated goal is child safety.”[16]

While children have the right to be placed in the “least restrictive, most family-like setting,” they are regularly placed in drastic alternatives like emergency shelters, hotels, institutions, and even the offices of the Idaho Department Health and Welfare.[17] In Idaho, children are also placed in homes rented and staffed by the Department, often in cities removed from their home communities and their families. Older children and those with disabilities face the most frequent overuse of institutional settings.[18]

A 2008 study by the Chapin Hall Center for Children at the University of Chicago found that children represented by attorneys in Palm Beach County had “significantly higher rates of exit to permanency” than children without access to legal counsel, while not decreasing rates of reunification.[19] Attorneys representing children can assist in moving the case toward permanency by independently investigating permanency options and advocating for the return of the child to parents when it is safe and appropriate to do so. Attorneys hold the Department of Health and Welfare responsible for its duty to care for children and provide reasonably necessary services and supports, as indicated in the court ordered treatment plan, to a family to facilitate the child’s exit from the foster care system and transition to a safe home. In this way, counsel for children provides a cost savings benefit to taxpayers by expediting the process to return home safely.

The child’s attorney focuses on the child’s number one legal problem – being in the custody of the state instead of a family. “Children have fundamental liberty interests at stake…” including the interest “in maintaining the integrity of the family relationships, including the child’s parents, siblings, and other familial relationships.”[20] While constitutional law is not often associated with child protection, the right to family integrity has long been recognized by the United States Supreme Court,[21] along with a recognition that “[n]either the 14th Amendment nor the Bill of Rights is for adults alone.”[22] Children’s representation should be important to all attorneys, as the child protection system and its outcomes (both positive and negative) impact nearly every other area of law and our communities. Children and youth deserve to be seen, heard, and well-represented. Their future, and ours, depend on it.

/*! elementor – v3.17.0 – 01-11-2023 */

.elementor-widget-image-box .elementor-image-box-content{width:100%}@media (min-width:768px){.elementor-widget-image-box.elementor-position-left .elementor-image-box-wrapper,.elementor-widget-image-box.elementor-position-right .elementor-image-box-wrapper{display:flex}.elementor-widget-image-box.elementor-position-right .elementor-image-box-wrapper{text-align:right;flex-direction:row-reverse}.elementor-widget-image-box.elementor-position-left .elementor-image-box-wrapper{text-align:left;flex-direction:row}.elementor-widget-image-box.elementor-position-top .elementor-image-box-img{margin:auto}.elementor-widget-image-box.elementor-vertical-align-top .elementor-image-box-wrapper{align-items:flex-start}.elementor-widget-image-box.elementor-vertical-align-middle .elementor-image-box-wrapper{align-items:center}.elementor-widget-image-box.elementor-vertical-align-bottom .elementor-image-box-wrapper{align-items:flex-end}}@media (max-width:767px){.elementor-widget-image-box .elementor-image-box-img{margin-left:auto!important;margin-right:auto!important;margin-bottom:15px}}.elementor-widget-image-box .elementor-image-box-img{display:inline-block}.elementor-widget-image-box .elementor-image-box-title a{color:inherit}.elementor-widget-image-box .elementor-image-box-wrapper{text-align:center}.elementor-widget-image-box .elementor-image-box-description{margin:0}

Jessalyn R. Hopkin

Jessalyn R. Hopkin is a Sr. Deputy Public Defender in Bannock County. She has spent the last four years specializing in juvenile and child protection cases. She is the Idaho State Coordinator for the National Association of Counsel for Children and is an at-large member of the Child Protection Section of the Idaho State Bar. The views expressed in this article do not reflect those of Bannock County offices.

Stacy L. Pittman

Stacy L. Pittman is a solo practitioner in North Idaho who practices across the state. She exclusively handles child protection cases, representing either the child(ren) or the guardian ad litem. Her previous experience includes working as a prosecutor, defense attorney, civil litigator, as a marketing and communications director in the health care field and working undercover for the police department in stings as a minor attempting to buy alcohol. She is a wife and mother who enjoys cooking, volunteering, and quoting Seinfeld.

[1] OFFICE OF PERFORMANCE EVALUATIONS, IDAHO LEGISLATURE, REPRESENTATION FOR CHILDREN AND YOUTH IN CHILD PROTECTION CASES, 2018, https://legislature.idaho.gov/wp-content/uploads/OPE/Reports/r1802.pdf. Children who come into foster care are often appointed a public defender or conflict public defender to represent them in a child protection case.

[2] Victoria Weisz, Twila Wingrove & April Faith-Slaker, Children and Procedural Justice, 44 Court Review 36.

[3] Right to Counsel Map, COUNSEL FOR KIDS, https://counselforkids.org/right-to-counsel-map/ (last visited September 4, 2023).

[4] Idaho Code §16-1614(1), Idaho Juvenile Rule 37(a).

[5] Id.

[6] Idaho Code §16-1614(1), Idaho Juvenile Rule 37(b).

[7] Idaho Juvenile Rule 37(a).

[8] Id.

[9] Idaho Code §16-1614(2), Idaho Juvenile Rule 37(a).

[10] Idaho Rules of Professional Conduct, Rule 1.2.

[11] Idaho Rules of Professional Conduct, Rule 1.14; see also American Bar Association Model Act Governing the Representation of Children in Abuse, Neglect and Dependency Proceedings, Section 7(c).

[12] I.C. 20-514(6); In re Gault, 387 U.S. 1 (1967).

[13] I.C. 20-514(5).

[14] As a juvenile attorney in Pocatello, Jessalyn and other attorneys in her office have been appointed to represent children as young as 7 in juvenile proceedings. Due to the confidentiality of the proceedings, some of which are still in process, specific names and cases cannot be discussed.

[15] Shanta Triveldi, The Harm of Child Removal, 43 NYU REV. L &SOC CHANGE 523, 524 (2019), https://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2087&context=all_fac.

[16] Id.

[17] https://idahonews.com/news/local/150-idaho-foster-children-spent-at-least-one-night-in-an-airbnb-in-2022.

[18] SARAH FATHALLAH, & SARAH SULLIVAN, AWAY FROM HOME: YOUTH EXPERIENCES OF INSTITUTIONAL PLACEMENTS IN FOSTER CARE, THINK OF US (2021), https://assets.website-files.com/60a6942819ce8053cefd0947/60f6b1eba474362514093f96_Away%20From%20Home%20-%20Report.pdf.

[19] ANDREW E. ZINN & JACK SLOWRIVER, CHAPIN HALL AT UNIV. OF CHICAGO, EXPEDITING PERMANENCY: LEGAL REPRESENTATION FOR FOSTER CHILDREN IN PALM BEACH COUNTY (2008), https://www.issuelab.org/resources/1070/1070.pdf.

[20] In re Dependency of M.S.R., 271 P.3d 234, 244, Wash. 2012.

[21] See Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U.S. 390 (1923), Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U.S.510 (1925), Troxel v. Granville, 530 U.S. 57 (2000).

[22] In re: Gault, 387 U.S. 1 (1967).